Jill Biden Is Exactly What Washington, D.C., Needs: A Philly Girl

The First Lady’s no-nonsense, relatable strength — born in New Jersey and forged in Willow Grove — is key to who she is and why she endures.

Dr. Jill Biden takes the stage at the Wells Fargo Center during the 2016 Democratic National Convention. Photograph by Tom Williams/Getty Images

This is not a political story.

This is not a political story for a lot of reasons — because it doesn’t have to be, because Jill Biden wouldn’t want it to be, and because the story of Jill Biden doesn’t start in the White House and certainly won’t end there.

This is a story that begins far from the capital — at least, far from that capital — in Hammonton, New Jersey, where Jill Biden was born. It’s a smallish town slivered halfway between Philadelphia and Atlantic City, the self-proclaimed Blueberry Capital of the World (the world!). The story winds its way up to the suburbs of Philadelphia, to Willow Grove, where she spent much of her childhood. This is where the story really takes off: where Jill Biden punched the neighborhood bully in the face for tormenting her sister; where she ran across the Pennsylvania Turnpike in the middle of the night to break into the local pool.

That’s where I am one sunny, snowy day in February, driving along that highway, on my way to find her childhood home in an effort to figure out who she is by seeing where she came from. It wouldn’t really matter (what does it matter what her old house looks like?) except for the fact that her being from Philly does matter, partly because Philadelphia and its surrounding suburbs are a large part of why she’s in the White House in the first place, and partly because in referring to herself as a “Philly girl,” she’s shaping the way the world looks at us (or, rather, reshaping it after Donald Trump’s infamous 2020 proclamation: “Bad things happen in Philadelphia”).

“You don’t screw around with a Philly girl,” Joe Biden said after Jill wrestled with an anti-dairy protester who’d stormed the stage during a Los Angeles rally last March. A month earlier, she’d politely but firmly escorted a heckler out of a speech in New Hampshire and explained after, “I’m a good Philly girl.”

Jill Biden with Joe on Inauguration Day. Photograph by Pool/Getty Images

Jill Biden fighting off a protester during the primaries. Photograph by Patrick T. Fallon/Bloomberg

This sort of toughness has long characterized Philly: We have grit and gumption, we don’t have time for bullies or bullshit, and we remember where we came from even after we’ve left. Even after we’ve made it all the way to the White House.

“People in Philly have kind of a dual personality: We’re blunt and honest on the one hand, but we’re warm and welcoming on the other,” says Steve Cozen, the founder of powerhouse Philly law firm Cozen O’Connor and a longtime friend of the Bidens. “We believe in community and we believe in taking care of our own, and it’s those traits, of both warmth and honesty, that typify Philly. And that typifies Jill.”

If ever a First Lady has had a dual personality — or, perhaps more fittingly, an alter ego — it would be Jill Biden. During her time as Second Lady in the Obama administration, she moonlighted as Dr. B., a professor of writing at Northern Virginia Community College. (She’d probably correct me here, scrawling a note in this margin with a red pen: For eight years of her 40-plus-year teaching career, Dr. B. moonlighted as the Second Lady.)

Dr. Biden famously graded papers on Air Force Two, requested that her Secret Service agents dress like college students so they’d be inconspicuous on campus, and headed for state dinners straight from school, shrugging into fancy dresses in cramped bathroom stalls. She’ll do it all over again, this time as FLOTUS — the first First Lady ever to have a full-time job while in the White House. That the First Lady is working as a full-time teacher at the exact moment our education system has been tipped on its head by a global pandemic, all of its flaws and fault lines exposed, is an auspicious coincidence.

In fact, Jill Biden seems tailor-made for this entire moment. Maybe it’s that she knows grief and how to heal from it: Joe’s first wife and baby daughter were killed in a car accident nearly three years before Jill met him, leaving him a single father of two young boys. The eldest son, Beau, died at 46 from brain cancer in 2015; Joe himself nearly died of a brain aneurysm in 1988. (“Get out of this room!” Jill screamed when she walked into Joe’s hospital room and saw a priest giving him his last rites. “Get out!”)

Maybe it’s her determination, maybe it’s her relatability, maybe it’s her warmth, the way she reminds some of us of an aunt, a mom, the nice lady down the street who calls you “hon” and brings you homemade lasagna. (Though not everyone’s mom, of course — Biden famously stumbled through her Spanish pronunciation during a speech to California farmworkers this spring.) Maybe it’s her toughness, or maybe it’s that this toughness is wrapped up in an accent that feels like home. Whatever it is, Jill Biden is a Philly girl, and right now, it seems like a Philly girl is exactly what the world needs.

But it’s not as simple as that. Even Dr. B. would probably remind me at this point that a good story needs some sort of tension. She says as much on the first page of her 2019 memoir, Where the Light Enters: Building a Family, Discovering Myself. “While not every tale needs a villain, every protagonist needs an antagonist — an obstacle to overcome,” she writes.

Hmm.

It’s easy to pinpoint Donald Trump as the antagonist, for all the reasons you’d suspect. There’s her ex-husband, too, a burly guy named Bill Stevenson who’s been peddling stories of an affair between Jill and Joe that he says happened before his divorce from her — gossipy catnip lapped up by people looking for more reasons to dislike them. (The Bidens, of course, brush these rumors off as patently false.)

I’m actually thinking of villains as I turn onto Jill’s old street and find her childhood home, which is a perfectly average red-shuttered split-level at the bottom of a perfectly average street. The bully lived somewhere in this neighborhood, and as I drive up the road, I imagine a fiery 13-year-old Jill marching up to his house (maybe it’s the cute brick ranch with the carport?), ringing the bell, and greeting him with a fist in the face. I keep driving up, up, up her sloping hill, searching for a way to start a story that’s been told a hundred times, when I finally reach a cross street. I glance up so I know where I am, and there it is, clear as day on a street sign in the middle of swing-state suburban America, at the corner of her childhood street: Division Avenue.

It’s so obvious, I start to laugh.

In the story of Jill Biden, the antagonist is us. It’s also this moment in history, when everything has been tipped on its head, an entire nation’s flaws and fault lines and fears exposed. We’re all grieving and scared and juggling and, most of all, angry. We’ve all lost something: a loved one, a job, a home, a year — an entire year — of life.

By all accounts, Jill Biden was the one to heal the Biden family, two little boys and a widowed father, back in 1975. She gave birth in 1981 to a daughter, Ashley, completing their family. She healed Joe, too, after his brain aneurysms, and she is healing the family again after Beau’s death. “It’s your strength and it’s your steadiness that holds this family together,” Hunter Biden said to Jill during his eulogy for Beau. “And I know you will make us whole again.”

This was presented as a matter of fact. But for now, for the rest of us, it’s a question: Can Jill Biden — First Lady, English teacher, Philly girl — make us feel whole again?

A life-size portrait of George Washington has hung in the East Room of the White House since 1800. In it, George stands with his right arm outstretched, as if he’s presenting the room in all its stately grandeur to visitors. Imagine Vanna White on Wheel of Fortune.

George has presided over a lot of things in this room: Abraham Lincoln’s funeral, Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act, Richard Nixon’s farewell speech, Barack Obama’s announcement of Osama bin Laden’s death. And today, one month into the Biden presidency, George Washington’s outstretched Vanna White arm presents: The Kelly Clarkson Show.

The likable singer turned television personality has been chosen for the First Lady’s first solo broadcast interview, and her crew has given the East Room a mini makeover for the occasion so that it loosely resembles her show’s boho-country L.A. set. There’s a trio of acoustic guitars next to George, a big circular rattan coffee table, and some mismatched area rugs patchworked atop one another. The whole thing feels a little jarring, as if HomeGoods has accidentally delivered a room’s worth of furniture to the (very) wrong house.

“Welcome to my house, the people’s house, your house!” Biden says, arms open wide, as she sits down for the taping. She’d been upstairs before this, watching the Villanova basketball game.

The show is a reintroduction of sorts to Biden, who for eight years was part of the country’s most famous foursome. People know her, of course, the way you know a Second Lady, which is to say generally not as much as you know the First Lady. Biden made her mark during the Obama administration, tackling a traditional trio of universal causes that she’s taken up again as First Lady: the military (With Michelle Obama, she founded Joining Forces, an initiative aimed at supporting veterans and military families); education, particularly the importance of community colleges; and cancer prevention. The work was — and still is — important (Joining Forces went dark during the Trump administration, but she reignited it as soon as she became First Lady), but it was her day job that caught the most attention.

“Jill is — oftentimes she’s grading papers,” Michelle Obama said in a 2016 interview. This is true: In Biden’s memoir, she writes about toggling between the two roles — doing her grading on Air Force Two returning from out-of-state events and squeezing into the school’s public restroom to change clothes for a White House reception. “I forget,” Obama said. “Oh yeah, you have a day job!”

“When I first met her, I didn’t realize that she had been a Second Lady of this country,” says Nazila Jamshidi, a 2019 Northern Virginia graduate who worked with Biden on women’s leadership and empowerment programs at the school. Jamshidi emigrated to the U.S. from Afghanistan in 2017, arriving to a whirlwind of unwelcome: Muslim bans, immigration restrictions, talk of a wall. That her professor had once been in such close proximity to the people who could put these into place — or prevent them — was unimaginable.

Of course, Biden’s relative anonymity was partly by design; if people asked, she brushed off the Vice President as a relative. She was there to teach, but it’s impossible to be a good teacher without learning something along the way.

“As a community college professor, she sees firsthand the difficulties and challenges that a student of color, a financially disadvantaged student, an immigrant or nontraditional student faces as they take a step toward education and achieving the American dream,” says Jamshidi. “It gives her a unique perspective about today’s American society, about today’s American struggle.”

Dr. Biden’s chances for anonymity now are slim. Despite her initial reluctance to wade into the political fray, Biden decided last January to take time off from teaching to support Joe’s presidential campaign, trading her classroom for a series of increasingly public stages — virtual fund-raisers, large drive-in rallies, and a prime-time DNC speech delivered from room 232 of Brandywine High School in Wilmington, where she taught English in the early ’90s. If she’d once been hesitant, there was no turning back: Jill was quickly regarded as one of her husband’s best political assets, a one-two punch of perspective and personality.

“I can tell you this one vignette from 2020,” says former Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell, who always has vignettes to tell. “We were having a major fund-raiser for Joe Biden. We raised, I think, almost two million dollars. But it was in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd being killed. Joe had gone out to Minnesota, and he wanted to spend time with the families, so he had to beg out of the fund-raiser.” This was a small problem, Rendell explains, because even though the event was virtual, there were at least 20 people who had either given or raised more than $50,000 for Biden, and they expected some face time with him.

“So Jill had to speak, and it was a somewhat disgruntled crowd. She spent the time not talking about policy so much, but about the personal characteristics that Joe has and why those personal characteristics will hold him in good status as president,” Rendell says. “And she blew the room away.”

It’s how most of Jill Biden’s speeches unfold. Aside from the occasional battle cry (“Are you ready to tell Donald Trump, ‘You’re fired’?!!!!”) and broad summations of Joe’s platforms, she focuses less on the politics of everything and more on the heart of it all. She’s there to harness the emotion of the moment, to humanize her husband, to smooth out — or smooth over — his rough spots. (“Oh, you can’t even go there,” she bristled to CNN’s Jake Tapper in an interview last September when he broached the subject of Joe Biden’s blunders. “After Donald Trump, you cannot even say the word ‘gaffe.’”)

“We didn’t book her ever with political reporters,” says Tiffiany Vaughn Jones, who was the press secretary for Pennsylvania during the Biden campaign. “That was a no-no. She didn’t want to focus on the politics of the campaign. She wanted to focus on connecting with people.”

And that’s why she’s here in the East Room, chatting with Kelly Clarkson over a vase of sunflowers. (“This is what I would say to you if I were your mother,” she says to Clarkson, before giving her advice on getting through divorce.) Because of the pandemic, she’s only face-to-face with seven virtual audience members, who look on, larger than life, from seven big rectangular screens. Throughout the hour-long show, Clarkson lets each one ask the First Lady a question.

“So what would you like to ask Dr. Biden?” Clarkson says to a man on one of the screens, who smiles broadly back at her.

But Biden — Dr. Biden? First Lady Biden? Madame First Lady? — interjects and proves that you don’t need to give the East Room a makeover to pull the First Lady down to earth: “Call me Jill! Call me Jill.”

Liz! Your girlfriend’s on!”

Stephen Leonard’s voice bellows through the house, and his wife, Liz, hurries into the room. Her old friend from high school, Jill Biden, is on television, and even though the last time Liz saw her was at Biden’s mother’s funeral in 2008, she still loves to catch a quick look at her when she can.

If she’s being honest, Liz Leonard had been hesitant to go to the funeral at all. At that time, Biden was the Second Lady of the United States, and even though the service was in Abington, Leonard expected a wall of security and red tape.

“Even Steve said, ‘Honey, I don’t think they’ll just let you into the church.’ But I got dressed normally and I went, and Secret Service were all around and … nothing! I just walked right into the front door of the church,” Leonard says. “I think that’s an example of how laid-back they are. They welcome anyone, and they’re happy to see old friends.”

At the end of the service, Leonard found Biden to offer her condolences: “And right away, it was as if we were back in high school. We both just started crying and hugging.” She pauses thoughtfully. “It’s funny — even though she was Second Lady at the time, it wasn’t on my radar then that, oh, Joe may run, and she may become First Lady. She was just my friend Jill.”

If the possibility wasn’t on Leonard’s radar in 2008, it certainly wasn’t back when Jill Biden was Jill Jacobs and Liz Leonard was Liz Esler and they were just two high-schoolers growing up outside of Philadelphia in the hazy, heavy days of the mid-’60s.

“We were normal kids, so into ourselves and our boyfriends. She was a cheerleader, and I was in the marching band,” says Leonard. After football games, they’d pile into cars and head to the Hot Shoppes in Jenkintown, a drive-in restaurant that’s now a CVS. They sat on committees together at Upper Moreland High School, planning the prom and the soph hop, and they had pajama parties at the Jacobs home. They cut school once, on senior cut day, with a bunch of other classmates. The whole lot of them got in trouble and had to do chores around the school for a week.

Biden’s rebellious streak isn’t a secret. There’s the well-worn story of how she broke into the Upper Moreland Swim Club as a teen, sprinting across the turnpike and scaling a chain-link fence at 3 a.m. Decades later, there’s the story of how, in 2003, she scrawled “NO” on her bare stomach and marched in a bikini through a group of party leaders who’d come to the house to convince Joe to run for president.

There are the lesser-known stories, too, like how at 15 she hung out her bedroom window and smoked cigarettes; when her dad found out, he made her smoke three cigars in quick succession in an attempt to make her sick and thus deter her from cigarettes. But he underestimated her stubbornness. Biden continued smoking, and eventually they reached a compromise: She could smoke, but only in the house. (It was the ’60s; everybody smoked in the house.)

In 2003, she scrawled “NO” on her bare stomach and marched in a bikini through a group of party leaders who’d come to the house to convince Joe to run for president.

She came by rebellion naturally. Her maternal grandparents didn’t approve of her father — a bank teller from a working-class Italian family (their surname was Giacoppa before her great-grandfather changed it to Jacobs upon arriving at Ellis Island) — so Biden’s parents, Donald and Bonny Jean, wed in secret. They lived separately in their respective homes in Hammonton for an entire year after the elopement until they finally had a small wedding and, before long, Jill.

Like those of so many Philadelphians, Jill Biden’s story weaves in and out of New Jersey from the start. She was born in Hammonton in 1951 but lived until age eight in Hatboro, in a tiny two-bedroom house in which she shared a room with her two younger sisters. (Two more sisters, a set of twins, would come later, when she was 15.) As Donald worked his way up, eventually becoming the head of a Chestnut Hill bank, the family moved — first back to New Jersey, living in Mahwah for two years, and then to the big split-level in Willow Grove. And though the Bidens’ current summertime home base is their $2.7 million house in Rehoboth Beach, Jill still has ties to the Shore — our Shore: She worked for two summers as a waitress at a long-shuttered seafood restaurant in Ocean City; her sister Jan lives in town and waitresses at a local breakfast spot.

After high school, Biden enrolled in Brandywine College (now Widener University) to study fashion merchandising, then transferred to the University of Delaware, where she majored in English. Here, she grew her white-blond hair down to her waist, wore clogs and bell-bottoms, and began noticing things that hadn’t really penetrated her suburban-high-schooler bubble: the feminist revolution, the Vietnam War, protests — over civil rights, over gay rights, over women’s rights.

“I don’t remember any protests held on my campus, but I might not have gone if there had been,” Biden writes in her memoir. “What, I wondered, would my voice add to this chaos? What would it mean to a government that didn’t seem to be listening?”

She was a newlywed then, married at 18 to Bill Stevenson, an ex-football player with a splashy yellow Camaro whom she’d met the summer after high school. They separated in 1974 and divorced a year later.

“I look back on it now and I think, you know, if I hadn’t gotten divorced, I never would have met Joe,” Jill Biden says to Kelly Clarkson.

The meeting of Jill and Joe is another story that’s been told a thousand times. Joe Biden, then a 32-year-old freshman senator and widower, was waiting for his brother to pick him up at the Wilmington airport when he saw an advertisement featuring a 20-something Jill Biden. (It wasn’t glamorous: The ad was for New Castle County Parks & Recreation, and Biden is quick to remind people that she didn’t get paid for it, so it wasn’t exactly modeling.) When his brother arrived, Joe pointed to her photo. That, he said, was the kind of girl he’d like to date. Turns out Joe’s brother knew Jill from college, and he passed along her phone number. (“How did you get this number?” she demanded when Joe called the next day. Their first date was a movie in Philly.)

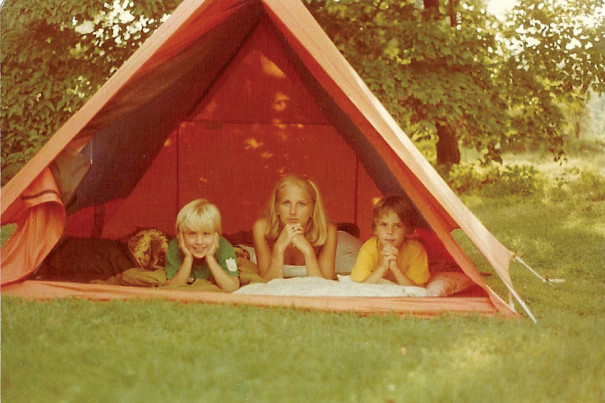

Jill Biden in 1976, with Beau (left) and Hunter (right). Photograph courtesy of the Biden Campaign

Jill Biden with Joe a year before they married. Photograph courtesy of the Biden Campaign

But a lesser-known story is that Jill already knew all about Joe Biden. You see, her first husband, Bill with the yellow Camaro, had been a big supporter of Joe Biden’s long-shot run for Senate in 1972. Jill, buried in her books, was less interested. (“What I wanted, desperately, was for the giant pile of Biden fliers to be cleared off our small kitchen table.”) But when Joe Biden won — barely, miraculously — Jill agreed to go with her then-husband to the victory celebration in Wilmington. She didn’t end up meeting Joe that night. Instead, she met his beautiful wife, Neilia.

It was a brief encounter — a congratulatory handshake — but it was enough to send Biden reeling when, a little more than a month later, she heard on the radio that Neilia and her baby daughter had been killed in a car accident. The other Biden children, two little boys named Beau and Hunter, were badly hurt. (Joe Biden was famously sworn into the Senate in Beau’s hospital room.)

It was because of the boys that Jill needed two years and several proposals to finally agree to marry Joe: “They had endured the loss of one mother already, and I couldn’t risk having them lose another,” she writes. They did eventually marry, of course, at the U.N. Chapel in midtown Manhattan in 1977, Jill, then 26, in a simple eyelet dress, the two boys standing at the altar with them.

The night she finally accepted Joe’s proposal — his fifth one — he hugged her. Then he pulled away, held her shoulders, looked her in the eyes.

“I promise you,” Joe Biden said to Jill, “your life will never change.”

Ha.

One blustery morning in mid-March, I find myself sitting on a tiny chair in front of an even tinier desk in the library of Samuel Smith Elementary School in Burlington, New Jersey. While oblivious children run around the school playground, bundled like marshmallows in winter coats, counter-snipers in tactical gear pace the school’s roof, police dogs sniff bags, Secret Service agents whisper into headsets, and assistants set up a microphone and podium. (“Do you want the American flag to the left or to the right?” a young guy asks a person in charge.)

Today, at precisely noon, the First Lady — Dr. B. — is coming to school.

Samuel Smith Elementary School is Jill Biden’s first stop on the Help Is Here tour. The Bidens and Vice President Kamala Harris and her husband Douglas Emhoff are crisscrossing the country to promote their ambitious American Rescue Plan, a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package. Biden arrives right on time and visits a classroom, crouching behind the children to watch them work and greeting virtual students. (“Hello! Nice to see all of you. I’m a teacher, too, but I teach English. Tomorrow I will be doing the exact same with my students!”)

Jill Biden visiting with Connecticut students in March. Photograph by Mandel Ngan/Getty Images

You may feel like you know Jill Biden, but when you see her in person, you find that she’s smaller, more energetic, more powerful and more normal than you think. As she gives a brief speech to a cluster of people in the school’s courtyard, backdropped by a plastic play set, she gestures emphatically with her hands, and her voice, pricked through with a Philly accent, carries easily over the wind.

“I’m always, always surprised at how she’s been able to get herself to a position where she can stand up in front of crowds of hundreds or thousands and talk about the things that her husband wants to do for this country,” says attorney Steve Cozen.

Nobody is more surprised by this than Jill Biden herself.

“I was never a natural as a ‘political spouse.’ As an introvert, I preferred to stay in the background,” she writes. Joe’s the extrovert, a practiced politician who unfurls in social settings like a flower in the sun. Jill’s happier in the shade of a classroom; over her 40-plus years as an educator, she has taught at a psychiatric hospital, a handful of high schools, and two community colleges, along the way earning two master’s degrees and a doctorate in education. But as her husband’s political profile grew, Jill had to learn how to speak in front of large groups, how to stump, how to work a room, how not to be so shy — and how to do all of this without losing her Philly-bred authenticity.

“You never get the feeling that while she’s talking to you, she’s looking over her shoulder to see if there’s someone more important to talk to in the room, which is a feeling many people get when they talk to politicians and politicians’ spouses,” says Rendell.

Former Bucks County Congressman Patrick Murphy agrees. “She is the most authentic, warm, charming person in political public service I’ve ever met,” he says.

Ask anyone about Jill Biden, and you’ll hear words like these tossed around a lot. (“I think if you knocked on the front door of the White House, they just might let you in — but you bring the chardonnay,” says Liz Leonard.) Or you’ll get a story, because, in typical Philly fashion, if you don’t know Jill Biden, you probably know someone who does, someone whose cousin went to school with her, or who worked with her dad, or who knows someone who dated her, or any of the other infinite ways you can be connected to someone when you live in the small-town city of Philadelphia.

Biden’s brand of homespun relatability may not seem particularly important now. Who cares how warm someone is when the country’s been set aflame? But in an era in which we’ve been trained to see those on the other side of the political aisle as dangerous — as corrupt or brainwashed, as racists or radicals, as enemies intent on destroying our way of life — there’s value in a person who can potentially bridge the divide with some good old-fashioned niceness.

It’s this mix of toughness and softness, of grit and grace, that makes Jill Biden feel familiar. It’s what made her such a crucial part of Joe Biden’s campaign (and earned her the nickname “the Closer”). It’s what healed her husband, and it’s what held her family together.

“Jill Biden reflects, in many ways, the time in which we are living. People are feeling worried and fragile, and there’s a couple in the White House who exude this caring, listening approach,” says Katherine A.S. Sibley, the director of American studies at St. Joseph’s University and a First Lady historian. “And the fact that they’re moderates is helpful, too. If they were maybe more progressive in their politics, there would be that edge a little bit. This, I think, bridges some of that.”

But don’t dismiss Jill Biden’s warmth as naivete. As authentic as it appears to be, it’s also a critical tool in cooling the political temperature, one that her notoriously elusive predecessor rarely deployed. There she is, patronizing Black- or immigrant-owned businesses unannounced and without her press pool in tow. There she is, dropping off cookies unannounced to thank National Guard members on patrol in D.C. for keeping her family and the inauguration safe in the shaky wake of the insurrection. There she is, on folksy Kelly Clarkson’s show, talking with a host who, despite leaning left now, once described herself as a “Republican at heart.” There she is, wearing a messy ponytail tied back with a scrunchie, juggling two jobs, walking the dogs, being, you know, human.

Rendell puts it simply: “Being First Lady won’t change Jill. Jill will change what First Ladies are all about.”

“This area teaches you to lead with your heart. To grow up with a rowhouse mentality, that you take care of the people on your left and your right,” says Patrick Murphy. “And this opens people up to be taken advantage of sometimes, but that’s when you see that Philly fight come out in her. She doesn’t take crap from anybody. Just because she leads with the heart doesn’t mean she’s soft.”

It’s this mix of toughness and softness, of grit and grace, that makes Jill Biden feel familiar to us. It’s what made her such a crucial part of Joe Biden’s campaign (and what earned her the nickname “the Closer”). It’s what healed her husband, and it’s what held her family together.

But it won’t heal us, and it won’t unite us, at least not entirely. No single person, however nice, could. She can give us hope, though — that maybe we can stop questioning everything and start appreciating qualities like authenticity and simple decency, like giant hearts on the White House lawn sending a message of unity to a country that’s forgotten how to love one another.

The trouble with starting a story is that sooner or later you have to end it, and it’s hard to end Jill Biden’s story when the latest chapter is only just beginning. I think back to a section in her memoir in which she wrote of the profound optimism of teaching. Perhaps that’s what we need, and perhaps that’s where this story ends. She might not be able to make us whole. But Jill Biden, a teacher from Philadelphia, is giving us much-needed — plain, powerful, profound — optimism.

And maybe that’s enough.

Published as “Jill Biden, Philly Girl” in the May 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.