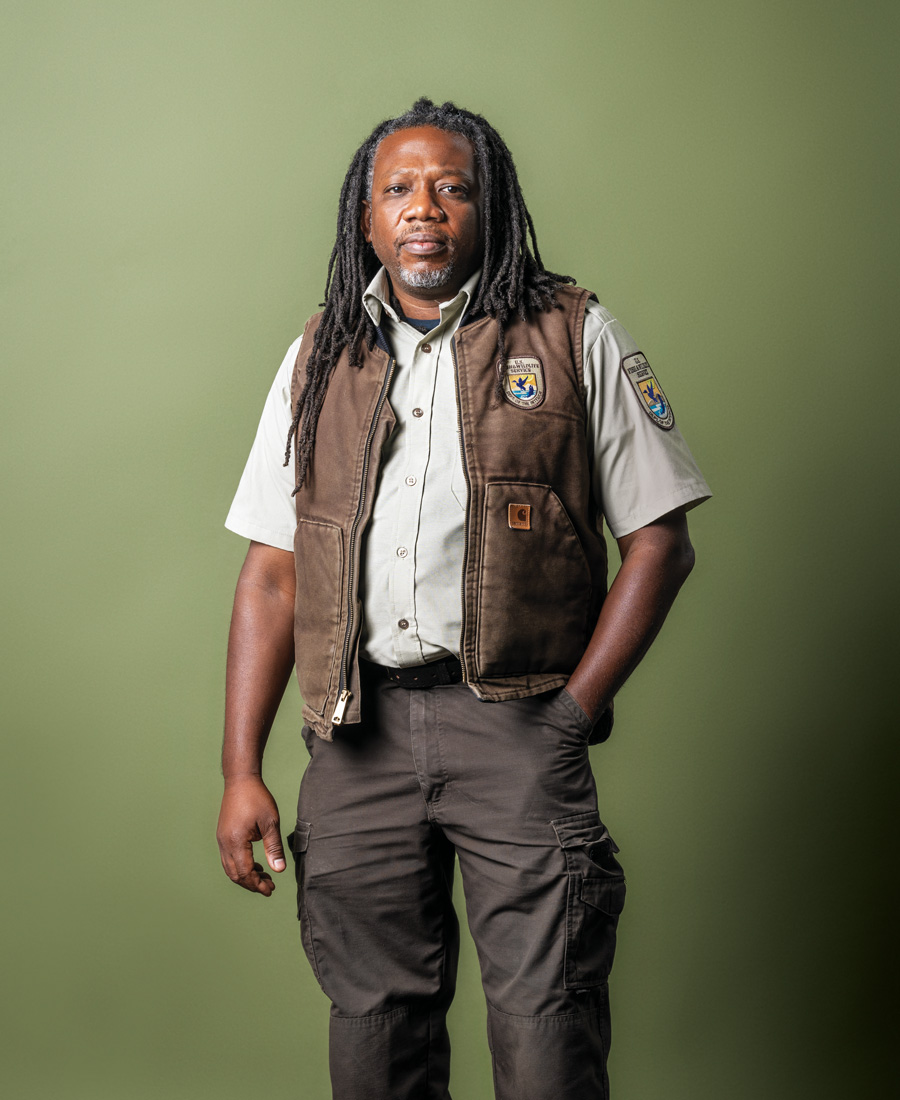

Lamar Gore on Helping Nature Through Climate Change, a Pandemic and Racial Inequity

As more Philadelphians seek socially distanced outdoor activities, the manager of Heinz Wildlife Refuge talks about what makes it “magical.”

John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge manager Lamar Gore. Photograph by Linette & Kyle Kielinski

As we’ve all been seeking safe, socially distanced outdoor activities during the pandemic, many Philadelphians have discovered John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge, those 1,000 acres of wetlands and forest jammed between densely packed Southwest Philly neighborhoods, the noisy airport and Delco. Refuge manager Lamar Gore, who has been at Heinz since 2014, talks to us about America’s first urban refuge.

Philadelphia: Say I’ve never had the pleasure of visiting Heinz before. Tell me what I’m in for.

Gore: It’s magical. Heinz is in one of the most developed areas in our country, but when you enter through the gates, you see all of this life. You can tune out the hustle and bustle, listen to the birdsong. You can see a fish jump out of the water and then see an eagle flying down to catch that fish. Then there’s the deer walking right by you in the woods. Oh, you see the airplanes taking off, and if you get too close to 95, you hear that. But you also see and hear so much peace. I enjoy watching a first-timer walking in and realizing the beauty that has been waiting here all along. I love that moment.

What does a typical day look like for you?

Zoom calls, phone calls, technical difficulties, repairing trail damage, fighting for money for my staff, going to community meetings, sitting down with a local elementary school’s principal, managing contracts, going downtown to meet with city officials on how to break down transportation barriers to not just Heinz but other green spaces in Philly, like Bartram’s Garden — there is no typical day.

I know that Heinz was closed for more than a month due to damage from that massive storm that ripped through here in August. Was that just bad geography and bad luck?

The problem is, you have two rivers coming together just outside of the refuge — Cobbs Creek and Darby Creek. Then you have the Clearview Landfill, the airport, and all the homes that have been built up around us. There is just nowhere for the water to go. Plus, that was truly a perfect storm. Lots of rain at high tide, and a full-moon high tide, no less. A true worst-case scenario.

What did the area around Heinz look like before the airport and all that development?

Imagine if you had a sandbox that was on a little bit of an incline, and water starts to come into it. The water flows and creates these veins, and you start seeing tendrils. So you have a main channel and all these connective waterways. People used to use these marshes for hunting birds and for fishing. Some people still fish out of this area today, but you might want to look at the consumption advisories for Pennsylvania’s waters before you do that.

I don’t imagine the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to be a particularly diverse employer. Am I wrong about that?

We’re not the most diverse of the various federal agencies. But we’ve been making strides, especially in the last eight years or so. Here at Heinz, we take diversity very seriously, and we are constantly working with our staff to think about the community that’s right here, especially Eastwick, Kingsessing and Elmwood. So the most qualified applicant for a job at Heinz isn’t always the person with the highest degree. They need to be able to reach the audience we are serving. We are looking at the institutional barriers that are in place that prevent culturally and ethnically diverse people from joining the Fish and Wildlife Service. We want to make this an easier landing strip for someone who looks different from a “typical” conservationist — or should I say, what most people think of as a typical conservationist. The truth is that conservationists come from everywhere. We just don’t tell those stories.

You don’t look like what I imagine most Americans think of when they think of conservationists. What was your path here?

I had an interest in nature and wildlife since I was very, very young. I grew up in Trenton, where I would play in the streams and ponds and in the marshes of the Delaware River. That was my thing. My family thought I was a little “off.” [laughs] So I always had this thing for nature, but I really didn’t know what to do with it. But then in sixth grade, I had this science teacher — Mr. Van Camp — who took every incoming sixth-grade class on a trip to Stokes State Forest for a week, and when on that trip, I realized what I wanted to do. So I went to college and got a bio degree and then to grad school for a wildlife degree — undergrad at Delaware State University in Dover and grad school at UMass Amherst. Two very different experiences.

“I realized that we cannot do conservation right if we’re not engaging and working with and celebrating nature with the community surrounding it.”

And then did you come right to Heinz?

No. Way. [laughs]. I actually stayed as far from civilization as I could, like in Vermont and this rural area in Virginia called Pungo. I had this purist biologist belief that you gotta save the land and restore it to what it was and keep people out of it so they don’t mess it up. But eventually, I realized that we cannot do conservation right if we’re not engaging and working with and celebrating nature with the community surrounding it.

What does working with that community look like?

Getting them to engage with the outdoors. Touching hearts, and breaking down the fear barrier that is in place because of our uniforms. We look kind of like police. But I’m a biologist. And the communities around here have been systematically excluded from the conservation movement.

I’m an avid user of the refuge, and I have to say that even though the Philly community right there is Black by a very large majority, the very large majority of the people I see using the park are not.

We are working to change that, and we have certainly seen an increase in Black and brown faces coming into Heinz and engaging with our outdoor events. We are actually studying that right now, and we should have some numbers to talk about within the year.

What are the unique challenges you face at Heinz?

Well, we talked about the flooding. There is just nowhere for the water to go when it needs to go somewhere. We need to keep the deer population down. And then you have crazy things like these turkeys. Turkeys love pecking on shiny cars. This one car that used to be parked right outside the refuge a lot got pecked all the time. We used to get calls from the owner about that constantly. People complain about the birds pecking on the wooden siding of a house. And we have over 300 species of birds that call Heinz their home. There are just all these things that happen when you have development right up against a natural area. Of course, we also have to deal with the increased levels of community fears of the refuge that are held over from the time of slavery.

How do you mean?

Growing up as a Black man, you are taught to fear going into a wooded area. My grandparents beat those fears into my head: Don’t go out there or they’ll string you up! I don’t worry about that here, but when I go camping in the middle of nowhere, I am definitely on guard. Like when I went to a deserted area of West Virginia for camping, was I on high alert? Yes. Because you never know.

Earlier, you mentioned the deer issue. Last year, Heinz debuted a new mentored deer archery hunting program, which my son and I were fortunate enough to take part in. I know the deer hunt is back and currently open, and yet a lot of people think it’s just crazy to allow hunting in something called a “wildlife refuge.”

We have to manage wildlife. We have too many deer. This is not the natural state. The predators that used to be here to manage the deer herds are no longer here. So the herds just continue to expand, which means more car collisions. They also unnaturally change the habitat. A deer herd can completely wipe out certain types of native vegetation. That’s not what you want.

And my understanding is that you had actually been culling the herd — though very quietly — using sharpshooters in the middle of the night.

We have been culling the herd since at least 2012. But I couldn’t justify doing the cull anymore without offering a public hunt, which is an opportunity to experience a unique recreational activity and provide food for your family and friends. Not everyone is going to agree with that. Some people simply believe that no animals should be killed.

Lamar Gore explores flooding at John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge this past August. Photograph by Linette & Kyle Kielinski

We’ve all had to adapt in this era of COVID. What has that looked like for Heinz?

We’ve adapted as best we could with online programming, and we’ve been doing a lot of livestreams from Heinz. Staff have been working around the clock to keep the refuge going, and that’s been very complicated. They are tired and burned out. And then you add to that the injustices that hit our community this year. I shouldn’t say they hit our community this year. They have always been here, but the difference now is that white America got to see it in a way they haven’t seen it before. And so we’ve had some conversations about all of that with the community. In June, I couldn’t figure out if I should say something publicly, and then some staff members came into my office and said we had to say something, so I spoke out on Facebook. I couldn’t stay silent.

What do you hope that people took away from what you had to say in your Facebook video about racial inequalities in this country?

I just hope that we can learn and grow from it and that it leads to more conversations with each other. We need a safe space for people to ask about issues of justice and injustice and prejudice and racism. We need to have these conversations and not worry about the fear of asking the wrong question. Does somebody want to be referred to as Black or African American or something else? That’s such a simple question, but people are afraid to ask even that question.

To that point, which do you prefer?

I mean, I prefer Black. But if someone is going to call me an African American, that doesn’t bother me one bit. I am both. But I think of myself as a Black man.

And as a Black man, what is it like being an employee of Donald Trump’s federal government, at least for now?

That’s a hard question. I’m not gonna go there. I’ll get in trouble for that. We have our ups and downs in each administration. But what I will say is that there has always been a challenge being a Black man in the conservation world. It’s an institutional thing that is carried within our culture and ethnicities, and we have to individually and personally take those things on. We need to stop treating each other like different species. We are all one species. It starts with the man in the mirror. The woman in the mirror. The person in the mirror.

Published as “Seeking Refuge” in the November 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.