Remembering Jim Quinn, Chronicler of Philadelphia’s Restaurant Renaissance

Critic, poet, language maven, and novelist Jim Quinn, a Northeast native whose career spanned nearly 60 years, died in September at 85. He spent two memorable stints at Philly Mag covering — and in some ways shaping — the city’s food scene.

Photograph by Michael Ahearn

Jim Quinn was one of Philadelphia’s finest, funniest, and smartest writers — of longform journalism, essays about food and language, and poetry for the first four decades of his career, and later of fiction as well. He was also, arguably, the city’s longest-living, longest-haired, and most prolific link to the best things about the 1960s, maintaining throughout his 85 years a sense of wonder and humor, political commitment, righteous indignation, and shrugging indifference to authority.

He was best known for his work for Philadelphia magazine — where he was a two-time finalist for the National Magazine Award and had a piece chosen for Best American Food Writing — as well as the Philadelphia Inquirer, the New York Times, Esquire, the Washington Post, and The Nation, and alt-weeklies that he outlived, including The Village Voice, The Soho News, Philadelphia City Paper and The Drummer.

Quinn could write the most gorgeous sentences. But much of the joy of his reportage was his amazing attention to details that told the story better than he could. “He describes everything, yes everything, in most specific terms since euphemism is a word he has never heard,” said the New York Times Book Review in 1972 of his first major book, Word of Mouth: A Completely New Kind of Guide to New York Restaurants.

The reviewer called it “the funniest book I have read in donkey’s years, funny enough to read aloud to guests.” In fact, the Times reviewer was so taken with Quinn’s writing — and his apparent “life style which inspires hostility from some restaurant owners, waiters and customers” — that she broke protocol (the early ’70s was still the ’60s) and insisted on having dinner with him for her piece.

“Mr. Quinn,” she wrote, “a mature young man, has really lovely waistlength hair which is offset by his beard, moustache and manly bearing. He was very neat and clean, wearing a dashing, but subdued‐in‐color crushed velvet suit.”

He was very opinionated, but not a loud talker; he made his points with a breathy laugh, and some of his words barely made it past his facial hair. (The beard was short-lived, the moustache lifelong.) But on the page he was always heard.

Jim Quinn was born in 1935, the first of five sons of an Irish couple in the Northeast; his father was a steelworker, his mother a homemaker. He went to Catholic school in St. Martin of Tours Parish, but had his issues with it from early on: He joked that he preferred to go to South Philly for confession “because the priests were more forgiving.” At 14 he broke up with organized religion and declared himself a Communist; classmate and lifelong friend Joe Chapman recalled the two of them being suspended from school after Quinn was overheard discussing socialism on the El platform.

When Quinn graduated from Northeast Catholic Boy’s High School in 1953, he received a Philadelphia Mayor’s Scholarship to Penn and a Navy ROTC scholarship to study at Columbia University; he chose New York. Within a year he had broken up with ROTC and left Columbia, but remained in New York, living a bohemian lifestyle (hanging out with artists Frank Stella and Carl Andre), taking classes at NYU, and working odd jobs.

He returned to Philadelphia, married and divorced, and worked for a trucking company and a medical supply house before being drafted into the Army. He tried to avoid the draft by relocating to Toronto, and then when he finally got his physical by refusing to sign the standard loyalty oath. He finally did serve, stationed in Alaska and South Carolina, but, not surprisingly, he had issues with military life. He married a second time, to a woman he met in the Army, and was eventually discharged. They had two children in the early ’60s, but the couple split and the kids moved to the West Coast with their mother. Quinn saw them mostly during summers.

In his late 20s, Quinn was convinced by friends to return to college. In 1963 he enrolled at Temple University, where he got involved in campus politics and anti-war protests.

Quinn, left, at a 1968 protest at Temple.

He created an alternative to the campus newspaper called The Other Temple News. After Quinn led a boycott of the campus cafeteria when it raised the price of coffee by two cents, his passion for writing about food was noticed by the publisher of the Collegiate Guide to Philadelphia — a popular annual alternative publication for local college students. He became the Guide’s restaurant reviewer. He was, at the time, working toward his PhD in English literature — writing a dissertation on the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid, and lots of his own poetry. But editors who were fans of his food writing started reaching out with assignments.

He wrote for Philadelphia’s major alternative weekly, The Drummer; in 1971 he published a book of political satire about President Nixon seen through the eyes of Lewis Carrol: The Campaign Alice: or Through the Election Booth & How She Lost Her Innocence. (He was proud it was reviewed positively by Screw Magazine, which loved the risqué illustrations, and The Militant, the publication of the Trotskyite Socialist Workers party.) He was then hired to write the New York restaurant guide Word of Mouth in 1972, and an updated version in 1973.

In the early ’70s he began writing for legendary Philadelphia magazine editor Alan Halpern. Quinn began with a piece about growing up Catholic and radical in the ’50s, and then became the magazine’s monthly restaurant writer. He wrote long, literary reviews — more in the style of Village Voice music essays than typical food reviews — that partly documented and partly instigated the Philadelphia Restaurant Renaissance.

In the October 1973 issue, he reviewed the breakthrough restaurants Friday Saturday Sunday; the Astral Plane; and Steve Poses’s original foodie masterpiece, The Frog. In a piece titled “Waiter, There’s a Long Hair in My Vichyssoise,” he declared that “War Babies” were “greening the gourmet restaurant scene.” Because this piece basically heralded the coming of a much-needed new era in Philadelphia dining, it is easy to forget that Quinn was not actually in love with much of the food he ate at these landmarks: He graded them B-, C+, and C, respectively. And while he did rate restaurants like this for many years, he grew to hate giving out ratings — his writing soared to new heights when he no longer had to and could focus instead on what was delicious and fascinating about restaurants and their owners and employees and patrons.

“To be honest, he felt he was writing about work,” said his wife Daisy Fried, the award-winning poet with whom Quinn spent the last 30 years of his life and raised a daughter, Maisie, now 13. “He was very interested in the work people did. It all went back to communism.” (Fried is not related to the author.)

Quinn worked on staff at the magazine through the ’70s apart from a six-month period in 1977–’78 when he was spirited away to the new Washington Post Style section, where he covered food, language, and popular culture. While he could churn out these smaller essay pieces — he was always an astonishingly fast and focused writer — he also periodically wanted to test his own range as a reporter. One of the last pieces he did for the Post was real-time coverage of the May 1978 standoff at the original MOVE house in Powelton Village. (Typical of Quinn’s politics, the piece was more critical of Mayor Frank Rizzo than it was of MOVE, which he described as “an organization … devoted to confrontation and to an antitechnology philosophy. Members, most of whom are black, refuse to cooperate with government authorities.” He quoted Rizzo calling them “absolute imbeciles … psychotics … they’re not even human beings.”)

Quinn returned to Philly Mag later that year, and besides his food writing, in 1979 he did a groundbreaking profile of Philadelphia Daily News columnist Pete Dexter, then 35 and starting to be taken seriously as a national literary figure. The piece, “Hawk Shadows,” was a finalist for the 1980 National Magazine Award for Essays and Criticism. Quinn left the magazine not long after, when editor Alan Halpern was fired, and was hired as food critic for the new alt-weekly The Soho News in New York.

That same year, Quinn published his second major book, American Tongue and Cheek: A Populist Guide to Our Language, in which he argued that English was becoming more and more democratized, and lampooned those trying to hold on to old formal usages. Critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt in The New York Times Book Review called the book “outrageous and delightful.” While he found some parts infuriating, he noted “as Mr. Quinn writes, ‘If this book doesn’t make you angry, it wasn’t worth writing.’”

In an interview about the book with Terri Gross on “Fresh Air” — when the show was in its local infancy, complete with call-ins — he defended words like “hopefully” that were coming into common usage despite the horror of the grammar police. He was astonished how worked up people could get about new words being accepted by the print media. “You can confess to the most horrible kind of sexual practices,” he joked, “and people will say ‘well, we have to understand that sort of thing’ [to] … show their tolerance. But say the word ‘irregardless’ and say you have no intention of dropping it from your vocabulary and they become utterly infuriated!” He preached “new words are new tools.”

He and Gross also had a funny conversation about the Philadelphia accent, which she was just learning and he was unlearning. “I can’t say ‘att-y-tude’ any more,” he explained. “But I remember we used to say ‘grat-y-tude, what a lovely at-y-tude for a ‘prost-y-tute’ to have.” Gross burst out laughing.

Among the language police Quinn criticized was William Safire, who at the time was two years into his “On Language” column for the New York Times Magazine. He not only appreciated the book by Quinn — whom he referred to as “a poet and food columnist” — but soon after reviewing it Safire invited Quinn to write the “On Language” column when he was on vacation.

“The idea that he could jump the gap from writing for alternative weeklies to writing Safire’s column for the Times, and stand in for the nation’s grammarian — amazing,” recalled bestselling author Steven Levy, who worked with Quinn at the Drummer and Philadelphia. “Such a renaissance guy, and also the ultimate free agent, always moving publication to publication.” Quinn also later wrote a language column for The Nation.

In the early 1980s, Quinn was hired by the Philadelphia Inquirer to do a different kind of food writing — a shorter weekly column in the Inquirer magazine about foodie culture. Many restaurateurs in greater Philadelphia and at the Jersey Shore, as well as many purveyors of ingredients and beverages, attributed their “discovery” and success to when Jim Quinn wrote about them.

Because many of these columns were timeless, he was able to file quite a few of them at a time and then travel for weeks or even months. He also worked on other projects, including his 1983 foodie insiders’ book But Never Eat Out on a Saturday Night.

When he returned from his travels, he would sometimes write ambitious longform pieces for Philadelphia under editors Ron Javers and Eliot Kaplan. In June 1988, he did a searing investigation into malfeasance in the Philadelphia Department of Human Services called “Dead Babies,” which was a finalist for the 1989 National Magazine Award for Public Interest journalism. In January 1993, Quinn wrote “In the Middle of the Battle,” an epic piece of immersion journalism about Philadelphia’s most famous chef, Georges Perrier at Le Bec-Fin — whom he had known since first reviewing the restaurant in 1973.

It was during this time that Quinn began dating poet Daisy Fried, who was 23 when they met, fresh from graduating from Swarthmore. They were a striking couple, both tall and self-deprecatingly funny with a lot of hair and strong opinions about politics and literature — and an age difference of 33 years that melted away as soon as you spoke to them. Quinn was starting to do more fiction writing, and the couple would often perform at the then-new Philadelphia Fringe Festival; they also freelanced at some of the same publications. (Daisy Fried covered women’s lacrosse and other subjects for Philadelphia during this time.) By 1996, Quinn had left the Inquirer — in part because the space for his column had grown so small — and then did a food column for Esquire, then Philadelphia Weekly and the City Paper.

In February 1999, when I became editor of Philadelphia magazine, the first thing I did was beg Quinn to come back and write a long monthly food column. By then his hair was a little shorter and all silver, his facial hair down to just a very thick moustache, and he always had a pair of reading glasses dangling from his neck. The very first “Quinn on Food” column was for Mother’s Day 1999 and it was all about moms and shad cutters and hot Korean bean paste and baked asparagus. And from there it went.

One of the best pieces was “Recipes for Dummies,” in which he went around to six top restaurants and got ridiculously simple recipes for wonderful things for which he and the chefs refused to share any amounts. The recipe for Jack McDavid’s “God’s Cherry Unjam” listed these ingredients: “Fresh cherries, sugar, a cherry-pitter.” That piece was selected, deservedly, for the book series Best American Food Writing.

In May 2000, his column announced that he and Fried were getting married. The theme was raw foods, and it ended with a recipe for the Chocolate Brandy Matzoh Cake, which they were going to make for their wedding — even though, he reported, “friends say this is a horrible idea. ‘You can’t have Raw Black Wedding Cake!’” But apparently you can, and they did. And lived happily ever after.

Since they each owned a book-crowded house in South Philly — his also home to his cats — they didn’t live together for their first two years of marriage: Quinn was back in school getting his MA in creative writing, and Fried was becoming a popular poet-in-residence, winning a Pew Fellowship and a Guggenheim. They finally consolidated their lives in Fried’s house (it was bigger). They had always planned to have a baby, and in 2007 Maisie was born. It was common to see the three of them — or sometimes just Quinn and Maisie (who called him “Jim”) — wandering around South Philly, which he liked to describe as “an area known for its huge outdoor market, its ethnic variety and in-your-face harmony.”

“He was a superb father,” said Fried, “spending hours playing games, reading to Maisie, and inventing stories for and with her. A favorite game was ‘Animal Psychiatrist,’ in which Jim, speaking in the voices of a series of Maisie’s figurines of real and imaginary animals, would come to Animal Psychiatrist Maisie for help with their problems, and Maisie would give them clear-eyed, practical advice.”

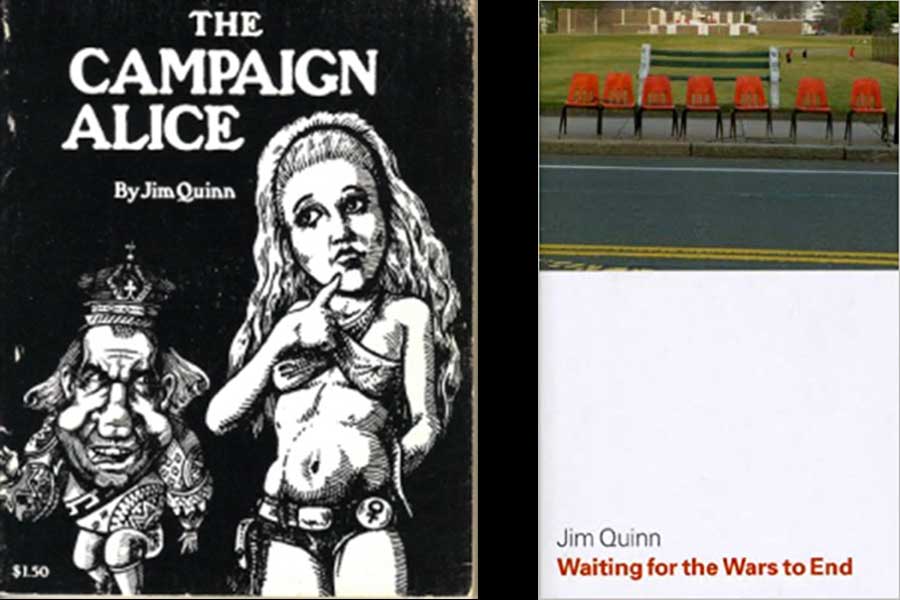

In 2012, at the age of 77, Quinn finished his final published book, a two-novella collection titled Waiting for the Wars to End, which he said was about “leftwing politics and strange sex.”

Quinn’s first book, left, and his latest.

Later in his 70s, Quinn began to experience very early symptoms of what he later learned was Atypical Parkinsonism. It didn’t keep him from completing two other novels, still unpublished, and spending quality time with his wife and daughter. He had several small strokes, but even they were handled in typically atypical Jim Quinn style: Because he was accustomed to playing funny and ambitious word games with Maisie, when he started spouting nonsense language she first thought was just part of the game. But after a quick trip to the hospital, they returned and all was well.

In the past year, however, his health deteriorated. Fried found herself in an epic struggle to get him home care, which she chronicled in long, often hilarious postings on Facebook. They were, in their own way, Jim Quinn-style columns about the work of taking care of Jim Quinn. In between posts about her multiple Zoom teaching gigs, her new poetry manuscript, and the two kittens she and Maisie brought into the house during Jim’s last days to keep him extra furry company, she told a daily, sometimes hourly story of being a caregiver, which was made even more challenging when covid-19 arrived.

At 9:15 a.m. on Wednesday, September 30th, Fried posted this from the hospice: “Jim Quinn is gone, peacefully, earlier this morning. I was holding his hand. A good man, a great writer, a great husband and father. I have been lucky to be alongside him almost 30 years. He was the one who made everything feel right, body, mind and soul. He gave us strength, courage, and so much fun.”

Jim Quinn is survived by his wife, Daisy Fried, and daughter Maisie Quinn; and children from a previous marriage, Charlotte Quinn and Michael (“Freedom”) Quinn. A memorial event will be planned for when the people who cared for him can get together again. Donations in his memory can be made to Community Legal Services, which helped Quinn and Fried navigate Medicaid.

Stephen Fried is a writer-at-large for Philadelphia magazine and a former editor in chief. An award-winning journalist and New York Times bestselling author, he teaches at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia, and lives in Bella Vista with his wife, author Diane Ayres. He knows this piece is too long, but so was everything Jim Quinn ever wrote.