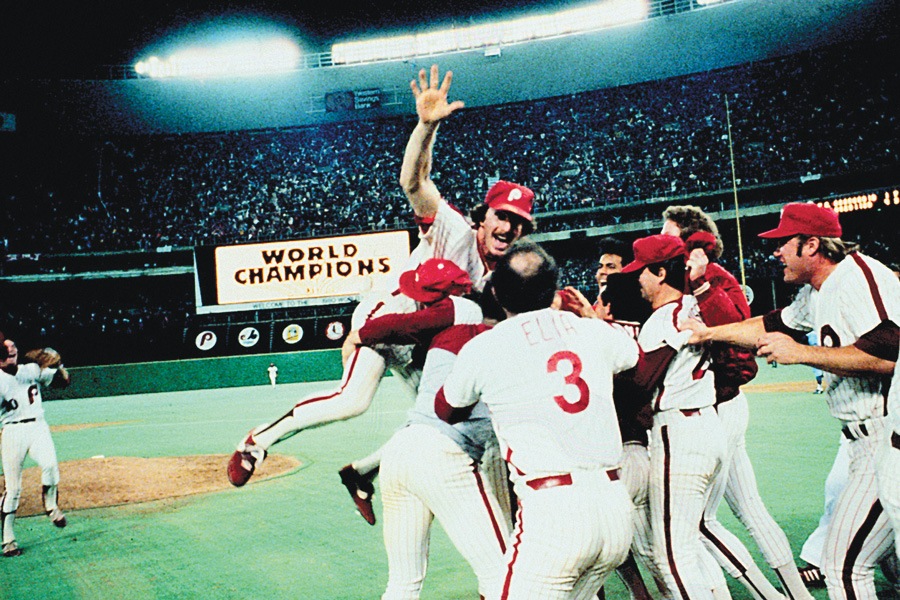

The Year We Won It All: An Oral History of the 1980 Phillies

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Forty years ago this month, an underachieving Phillies team gave a skeptical, down-on-its-luck city something it hadn't seen in half a century: a World Series championship. From clubhouse fights and on-field drama to disco lessons and perms, here, in the players’ own words, is how it all went down.

Mike Schmidt celebrating the 1980 Phillies World Series win. Photograph courtesy the Phillies

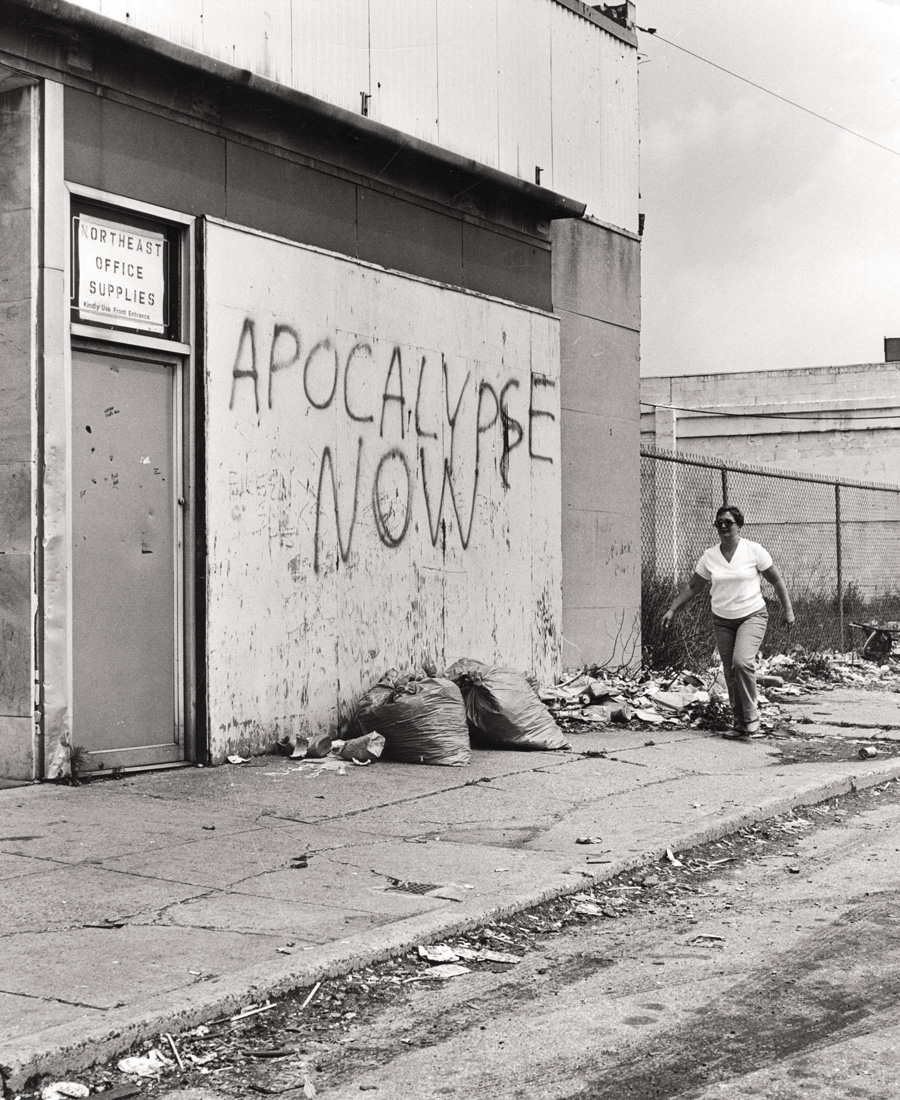

It was a different city then, in 1980. Bill Green had just become mayor after eight years of Frank Rizzo’s reign.

As Sam Katz (who would run for mayor himself three times) describes Philadelphia 40 years ago: “I would say it was a disaster. The residue of the Rizzo years was palpable in every aspect of life. The city was bifurcating very rapidly. You had a very divided city.

“All the stereotypes that surrounded Philadelphia’s reputation were in full gear. Philadelphia was politically weakened, racially stereotyped, economically flatlined. Green certainly was a breath of fresh air for reformers, but whatever administration he put together, it wasn’t felt yet in 1980, other than Frank Rizzo wasn’t mayor.”

It was, you might say, a tough time for the city.

And in some ways, Rizzo’s presence not only lingered, but seemed to foreshadow the current environment. “Bill Green issued a deadly-force policy that basically indicated when police could use their weapons,” remembers Wilson Goode, who was Green’s managing director before becoming mayor himself. “And I remember that time [in 1980] precisely because I know whenever Bill Green or I went out, police officers had a habit of saluting, were required to salute the mayor and managing director. Now, they would all turn their backs on us.” There were 437 murders in Philly in 1980.

A graffitied wall in the Northeast in 1980. Photograph by Sam Nocella/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

The city’s sports teams were no help in alleviating the mood. The Flyers had won the Stanley Cup in ’74 and ’75, but the other three major teams — the Sixers, Eagles and Phillies — hadn’t brought a championship to the city in more than a decade. The Phillies never had. “I think it would be fair to say that most fans of the Phillies were still picking the scab of 1964,” says Katz. That was the year the team blew the pennant by losing 10 games in a row at the end of the season.

“We were all tuned in to Philadelphia as a city — we felt what the Philadelphia fans felt,” says Mike Schmidt, who was in the middle of his Hall of Fame career with the Phillies in 1980. “We knew how much it hurt them for us not to get in a World Series and win it all, because we had great talent for three years, and we failed in the postseason [in 1976, ’77 and ’78]. And I think it made us all very, very hungry. But it also kept the pressure on. … You know, you end up maybe trying too hard. But the bubble burst there in 1980.”

It was a team, as Schmidt says, of great talent, developed in the Phillies’ farm system and obtained in trades. But those failures in the late ’70s had the city skeptical that this group could break through. The local media, rougher then than now, called the team pampered, underachieving chokers for those losses in the playoffs in the late ’70s.

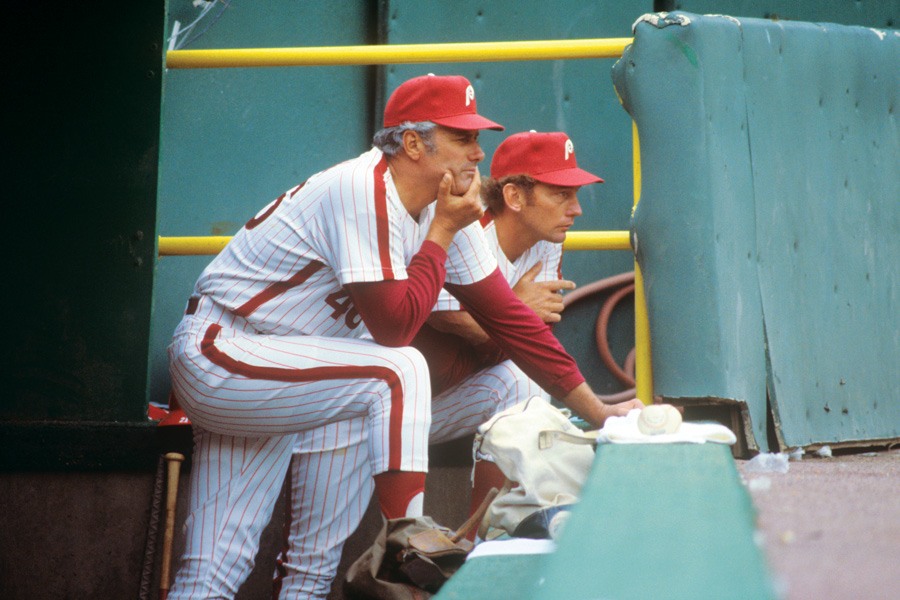

But two things had changed by 1980: free agent Pete Rose (actually signed the season before), and a new manager, Dallas Green. Rose was known for his über-confident, hustling style of play with the Cincinnati Reds. Green, who ran the team’s farm system for most of the ’70s, was strikingly handsome, huge at six-foot-five, and a take-no-prisoners leader. Fired manager Danny Ozark had a light touch; Green was much more likely to scream at his players in the dugout, then tell the press exactly what he thought.

Things were different, all right.

Dallas Green Has a Message

Green started off spring training in 1980 by hanging signs in the clubhouse that sent a message: “We, Not I.”

Lee Elia, third-base coach: I think that was a profound three words, and I think it really meant something to him.

Ray Didinger, columnist who changed papers that August from the Bulletin to the Daily News: Dallas had no problem calling out the players. He had no problem naming names. He had no problem pointing fingers at a team that had been coddled by Danny for as long as they were. Danny totally covered for those guys, which was part of the problem. It was a total 90-degree departure, and they didn’t like it even a little bit.

New manager Dallas Green with coach Bobby Wine. Photograph via Getty Images

Larry Bowa, shortstop: I think Dallas was very important in winning the World Series. He motivated us. He wasn’t afraid to bench guys if they weren’t playing good, you know, and he had a meeting when he first came down: “You guys think you’re better than you are — you haven’t done anything.” When he said that, it got people’s attention, because we had done some things. I sort of like that stuff. There’s some guys who don’t like it. It didn’t bother me at all. I think we have the same personality. [Which is why Bowa sometimes criticized his manager publicly on his radio show.]

Greg Luzinski, left fielder: I went to see Dallas in his office. I said to him, “If we do something wrong in a game or something you disagree with, why do you give it to the press? The team wants you to come to us individually.” He slammed the door. I was still in there. We talked for a while. I walked out, there were 10 press people standing there, probably their ear to the door. They started asking questions — it made headlines and everything else.

Didinger: Dallas never really called out Mike Schmidt. He would say to the team, “We got too many guys in here who have to stop being so effing cool.” Whenever he talked about too many guys in here trying to be Joe Cool, that was Mike. But he would never call him by name. It was actually very canny in that way, because when he said it, everybody knew who you’re talking about. And Mike knew who he was talking about. But he never put the finger on him, because he wasn’t quite sure how Mike would react to being singled out.

Del Unser, part-time outfielder: There was no other guy on the team that was going to take it to you like Dallas would. Yeah. Some guys like to think they’re leaders and this and that, but when we needed a kick in the butt, he’s the one that did it.

Dickie Noles, a pitcher in his second year: One time, Dallas told me I was like a mustang: “I am going to break you.” Oh, he did — I mean, he broke me. But in a good way. I owe Dallas Green just about everything I can possibly think of when you start putting things together, from the time I started in baseball to the time I ended it. Without Dallas Green, I’m not too sure I would have had much of a career.

Mike and Pete

Mike Schmidt, third baseman: When I first came to the Phillies, guys used to kid me about striking out. They had this one thing with a sneeze: They’d go achoo when I came back to the dugout. They thought they were making a joke about my swing creating this wind, but that hurt, that hurt when they did that. … You end up pushing somebody against the wall in the dugout. And that’s not good.

Bob Boone, catcher: I remember sitting on the bench with Mike and he said, “You know, I really had a lot of power when I was in college.”

Schmidt: Oh, I would say there was some merit to that label [that Schmidt wasn’t a clutch hitter]. I’m saying it from knowing how I felt personally, knowing whether or not I was comfortable being at home plate with the game on the line. Later on in my career, I got very comfortable with it. I actually wanted to be up there then. And I think that if you understand what fear of failure means, I think I had it early in my career. I think I probably was overly stressed in those kinds of situations. I don’t know that I was built for that.

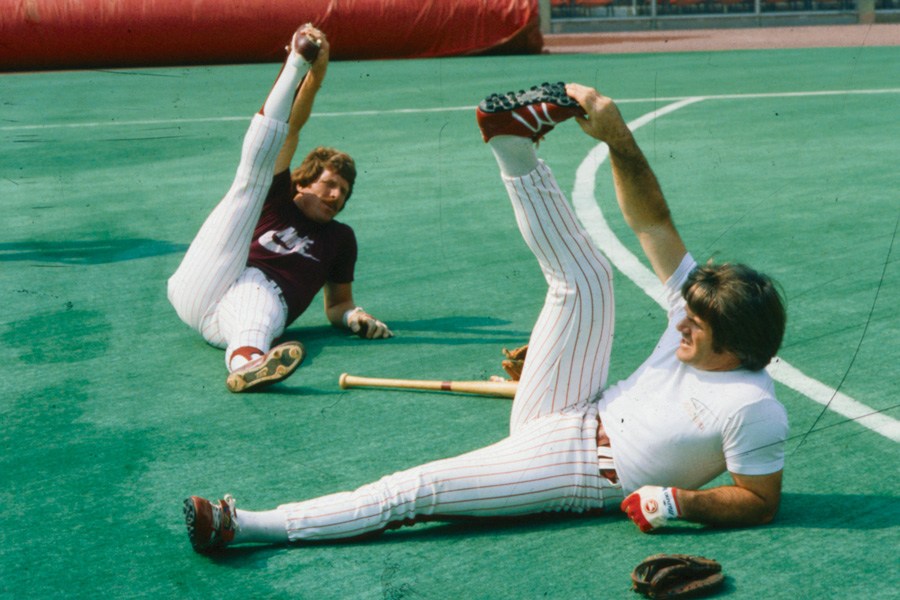

Mike Schmidt and Pete Rose warming up at the Vet. Photograph via Getty Images

Boone: Pete Rose went to Mike. He knew how talented Mike was. And he was constantly saying that to Mike, how good he was: “You’ve got to understand how you’re a great player. You’ve got to know that.” Once he knew that, it was over.

Ozzie Virgil Jr., a catcher called up from the minors in September: Pete was the leader on the field. I mean, you watch Pete. And then another thing that I got to see: If Pete went zero for three or four, he’d go in the batting cage after the game and start hitting. And I was like, isn’t that guy tired? He’s an older guy. And every day I thought, wow, that’s pretty frickin’ impressive, you know?

Noles: Pete Rose never missed a pitch at a baseball game, ever.

Schmidt: Pete helped a lot. A lot. I’m very influenced by people saying the right things to me at the right time.

Bowa: I think Pete took a lot of pressure off, with the media and everything — you know, nothing bothered Pete.

Schmidt: It was uncomfortable for me to go downtown just because you’d be recognized. I mean, I was pretty recognizable back then. Not now at all. I go walk around Philadelphia all I want now. Nobody even turns a head, which is kind of nice.

But They Did Have Fun …

During the off-season, with many of the players staying in or near Philly year-round, the Phillies had a basketball team that played exhibitions all over eastern Pennsylvania against high-school faculties and boys’ clubs; seven or eight players would pile into a couple cars and head, say, to Allentown. They’d each get $90 to play — including Schmidt, who had two bad knees.

Schmidt: I was crazy to be playing basketball. My left knee was rebuilt in 1967 [when he was in high school], a total reconstruction. I just had my fourth operation on my left knee, and I’ve had three on my right knee. I’m going to get the left one replaced in the fall when I go back to Florida. That knee should go to the Hall of Fame, not me.

In the late ’70s, relief pitcher Tug McGraw helped bring the team closer by organizing long bike trips — one winter, it was from Philly to Clearwater; the next, down the West Coast from Washington deep into California — to raise money for muscular dystrophy.

Larry Christenson, pitcher (known as L.C.): The first year, Tug, Steve Carlton, Jerry Martin, [Eagles quarterback] Roman Gabriel and I left Philly in, like, 10 and a half inches of snow. We got across the Platt Bridge, we loaded up the bikes in the trailing van, and we drank beer all the way to the White House, then tried to bang on the door to get Jimmy Carter to come out and say hi. But he wasn’t there — we got turned away. Then we were biking, like, 100 miles a day.

We played basketball on the trip. We played in Plains, Georgia. We met Miss Lillian [President Carter’s mother], and Tug had gotten drunk on Jameson and fell off his bike in front of her. Before that, we went to Billy Carter’s gas station and drank Billy Beer. Roman Gabriel’s pouring Billy Beer out, saying, “This tastes like cat piss.”

When they got to Florida, L.C. discovered something in the clubs: disco dancing.

L.C.: It was the best thing I ever did. I had more fun because of all these discos — Second Story and Élan and all those in Center City — that we went to. Matter of fact, the following spring training, Steve Carlton and Tim McCarver took, even with their families, disco dancing lessons. But I think the critical lessons were in the locker room, when I turned boom boxes on. And I’d grab guys. I’d say, listen, I’m the leader, you’re the follower — you’ve got to be the girl. Schmidt was one of my partners in the locker room.

Noles: L.C. was always teaching us something.

L.C.: Pete had three girlfriends going at the same time. I called them Door Number One, Door Number Two and Door Number Three. And half the guys got perms. [Among them were Schmidt, Bowa and Luzinski.]

Ron Reed, relief pitcher: One of my best friends on the team was [outfielder] Bake McBride. I spent a lot of time with Bake. He was always giving me a hard time: “You could probably pitch better if you got an Afro going.” He had to pin his hat on with bobby pins to keep it on; he had a giant Afro. I went to a beauty parlor, with pink curlers in my hair, and got a perm as high as Bake’s. When I showed up in the locker room, he gave me a high five.

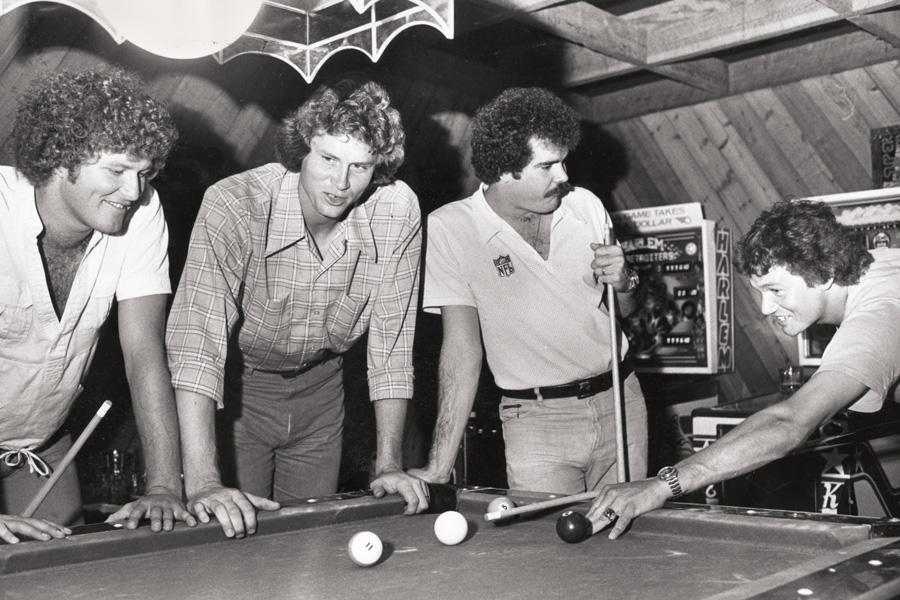

Pitchers Marty Bystrom, Jim Wright, Kevin Saucier and Dickie Noles — and their perms — playing pool during spring training. Photograph by Joseph P. McLaughlin/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

Even pitcher Steve Carlton, who seemed to live in his own world and refused to talk to the press after Daily News columnist Bill Conlin exposed his night-before-a-game carousing in the early ’70s, got in on the dancing.

L.C.: Lefty was into kung fu disco dancing. He had his own style. … But I remember even during the ’80 celebration of the World Series, he tucked away in the training room, and there was newspaper or some paper covering the windows. So nobody could look in there.

Didinger: [on the relationship between the media and the team] It was the most uncomfortable experience I’ve ever had as a journalist in 50 years, as a writer going in [that clubhouse].

Two years earlier, after Ray Kelly of the Courier-Post wrote a column critical of Larry Bowa, Didinger walked into the clubhouse with Kelly.

Didinger: Larry jumped right in Ray’s face, started calling him all kinds of names, with every curse word you could possibly imagine. And now it became physical. It became push-and-shove physical. And it winds up with a clubhouse table getting knocked over, and Ray winds up with a bruised eye. There’s a scramble. Players are grabbing guys and pulling guys away. And I’m basically collateral damage.

Bowa: I got knocked down a lot. Trust me. I got knocked down. I read all the negative articles. That’s cool. Every negative article I read, I said, okay, we’ll see how it turns out.

Unser: [on Bowa’s intensity becoming too much in the locker room] Sometimes it got to the point where Ron Reed [who, at six-foot-six, had played forward in the NBA] might just hang him up in a locker, on a hook. He’d be chirping and chirping and sometimes he’d over-chirp, and Bigfoot would take care of that and it would be funny. It wasn’t like they were going to fight.

L.C.: Lefty would lie on the training table before the game he pitched. I’m thinking, well, he’s taking a nap. No, he wasn’t taking a nap. He was visualizing what he was going to do, blocking out the hitter’s part of the plate and only thinking of the pitches outside, inside, low, high, but never the middle of the plate where the bat comes across with the fat part. He would block that out.

Bystrom and Noles after winning the pennant in Houston. Photograph by Associated Press

Noles: I don’t remember a lot about what I did, but I did a lot more than most players on that team, because I was out far too much. It didn’t take much to get me out, because I never wanted to go home. And I seemed to attract trouble for some reason.

Virgil: [on rookie players getting hazed] We just finished playing in Houston. We get back into the clubhouse, and all my clothes are gone. And I got stuff in there from the 1960s — bell-bottom pants, high platform shoes two or three inches, and a psychedelic shirt. We had to wear that to the airport, they made all the rookies wear it. We looked like flower children from the ’60s. [He laughs] I was kind of upset — we never got our clothes back.

A Season Turns on Tough Love

In September, after a disastrous couple of games in San Diego, general manager Paul Owens paid a visit to the locker room.

Manny Trillo, second baseman: It was a meeting in San Francisco in the clubhouse with Mr. Paul Owens, and he was really tough on us. I think he was tougher than Dallas. He said, “If you want to fight me, you fight me. You gonna give me a black eye, I’ll put a piece of meat on it, and I’ll come back again tomorrow.” After that, we said, geez, he wants to fight, geez. It was a good talk.

Noles: I don’t think there was a guy in that place at that moment that was going to mess with Paul. So I think everybody just kind of sat there and took it, and it did inspire us. I think it woke us up. I think we went 25-7 after that.” [Actually, they went 23-11.]

Outfielder Garry Maddox. Photograph via Getty Images

Didinger: Dallas was really tough on Garry Maddox [the team’s center fielder]. His whole approach, the whole “Mr. Bluster, I’m going to peel the paint off the wall” kind of thing. It was very opposite of Garry’s personality. Garry is a very sensitive and sort of introverted kind of figure. And that kind of stuff — it bothered him; it didn’t motivate him. When Garry went through some tough emotional times that year, especially in September when Dallas benched him, Garry was really down. Really down. And I remember seeing after games in the locker room off into the corner, it would be Garry sitting with Rich Ashburn [the team’s announcer and a former player], and just the two of them talking.”

Garry Maddox, center fielder, speaking on WIP earlier this year: Dallas was on you all the time. That kept you sharp and kept you always kind of looking around. … It looks like good managing today. [laughs] At the time, I thought it was something different.

Near the end of the season, Dallas Green benched stars Maddox, Boone and Luzinksi for a stretch of games.

Didinger: The pennant’s hanging in the balance. We’re like two weeks left in the season, he benches three of his core players for a career bench player in Del Unser and two kids. … That could have blown up the whole team. But they rallied. And then in the playoffs, he goes back to his veterans, and they all deliver for him.

Unser: [on having to replace Maddox in the outfield] I was [pissed] at Dallas because he was messing with my World Series money. Maddox is the Secretary of Defense [a name bestowed by Bill Conlin for his stellar work in center field], and I couldn’t run like hell anymore. I was pretty quick when I was younger, but here I am, 34 or 35, going down the stretch. But the one benefit was that I got my timing back pretty good and got a couple big hits during that stretch.

Virgil: Guys all work together for one goal, and then it’s in their fingertips and they’re all, like, playing the game. They’re playing the game, the baseball, the way it’s supposed to be played.

The Postseason

The Phillies faced the Houston Astros in the National League Championship Series.

Boone: Because of our losses in the postseason in the late ’70s, we really felt it was do-or-die. We felt that way.

Bowa: We knew all about the history of the ’64 Phillies, how they blew the lead and all. We were constantly reminded of that.

In the fifth and final game of the series, the Phillies were down three runs in the eighth inning against future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan.

Bowa: Pete said, “If you get on, we’ll win.”

Bowa singled. Several batters later, Trillo hit a triple that tied the game. The story goes that Lee Elia, who was coaching at third base, told Trillo he loved him when he arrived there.

Elia: We were all in another dimension. And when he came to third base, I grabbed him. I don’t remember saying “I love you,” but I forgot that I was on TV for that moment, and when I realized it, instead of kissing him, I bit his ear.

Unser: The noise of the crowd in Houston was definitely why I have hearing aids now.

After Maddox got a big hit and caught the final out in Houston to win the pennant, his teammates carried him off the field.

Didinger: And the guy who’s got Garry by the right leg right there on his shoulders is Dallas. Yeah. And here’s Garry with this smile that’s lighting up the whole Astrodome. … Three weeks earlier, they couldn’t stand the sight of each other.

Unser: There are people out there beyond the cyclone fence at the airport [when the team flew back to Philadelphia in the middle of the night]. Wow. I couldn’t believe there were people there at four in the morning.

Boone: There were so many big hits and so much good pitching [in the Houston series]. And when we finished it, I think we felt as a team, “We’re going to win [the world championship].” And there was a calm that came over us. We’re all playing really good. And we just went into it very relaxed, into the World Series.”

The Phillies faced the Kansas City Royals in the Series. After the Royals’ Willie Mays Aikens hit his second home run of Game Four and posed for too long at home plate admiring his work, Dickie Noles knocked down Royals star George Brett with a pitch near his head.

Boone: It scared me.

Noles: When I knocked down Brett, I’m not too sure what would have happened if Rose didn’t come in side by side with me and take that whole situation over. He could outtalk anybody on the field.

When [Royals manager Jim] Frey came out of the dugout, the crowd booed, and it was pretty intimidating. Frey yelled, “Stop it right now, stop it right now.” Rose goes up to him and goes, “Shut up and get off the field, Jimmy. He wasn’t throwing at him.” Frey says, “How do you know?” Pete says, “If he was throwing at him, he would have hit him.” It kind of tongue-tied Frey — he didn’t say another word. Rose told him to get off the field. Then he told me to pitch my own ballgame. Their whole dugout could hear that — he was looking right in their dugout.

I am so happy the ball did not hit the great George Brett in the head, because I would have been the biggest villain in baseball history.

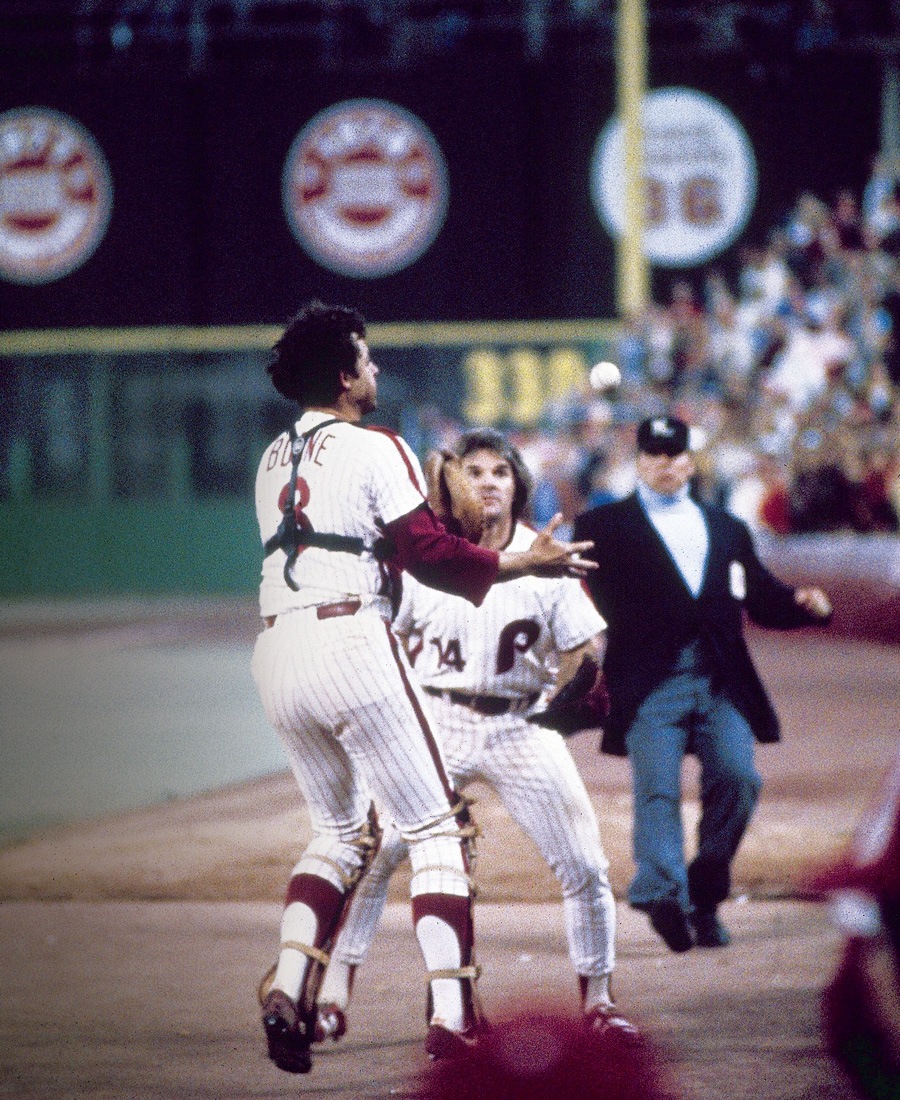

Bob Boone, Pete Rose and that fateful foul ball in Game Six of the World Series. Photograph by Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Even though the Phillies lost that game, many observers credit that knockdown of Brett with helping the team take control of the Series. Going into Game Six, the Phillies were up three games to two.

Boone: [who has a degree in psychology from Stanford] The last game, McGraw came in, and Tug was wild — Tug was never wild. Warming up, every pitch I caught was high, above my head. Tug and I were really good friends, and he had that look like, “Come on, Bob, I know you know what I’m doing wrong. Come out here and fix me.” And he started the inning off walk, walk, and every pitch was up. I was watching like crazy, trying to figure it out. I never liked to go to the mound unless I had something to say. And he was in enough trouble, you can see it in his eyes — panic. I’ve got to go out there. I take my time. I said, “Tuggles, everything’s high.”

I turned and walked away — by the time I got behind the plate, he’s out there laughing. And all of a sudden, he turned into Tug McGraw.

John Middleton, now the Phillies’ owner, then a young guy with nosebleed seats for the game: I would have hung on for dear life to a light pole in the outfield, just sticking up there on the roof somewhere.

Goode: Bill Green told me it was my job to go to the last game and take a seat next to the Pope [Phils GM Paul Owens]. He said it was my job to keep him from getting drunk. And he was just drinking one beer after another. Oh boy — I was going to fail at this. This man is bigger than me, he’s general manager of the Phillies, he’ll do what he wants to do. I can’t tell him don’t drink anything else. …

He got tanked. I think Green was concerned that Owens would embarrass himself and the city. But when I left him, he was still able to walk around.

Middleton: There was an enormous amount of angst. The collapse in ’64 was part of it, but it goes to those [missed chances in] ’77 and ’78 — that was palpable. If you were standing in the concession line, you could hear people talking about that: “Oh my God. What’s going to happen?” That sense of, there’s so much hope, but also the sense of impending doom.

In the ninth inning, with the Phillies leading 4-1, the Royals loaded the bases. The Royals’ Frank White hit a foul pop-up that bounced out of the mitt of Bob Boone, but Pete Rose was there to snag it.

Middleton: In that split second, everybody saw disaster. And all of a sudden, it’s, Oh my God, it’s on again.

“In that split second, everybody saw disaster,” remembers John Middleton. “And all of a sudden, it’s, Oh my God, it’s on again.”

One batter later, McGraw struck out Willie Wilson to end the game.

Katz: Winning was a great moment, but it still came as a shock, because we had this disease where we had this spell that had been cast over us. Me personally, I was prepared for a bad outcome. I had been trained to expect a bad outcome. Whether people were as excited to win the World Series as we were to avoid losing one, I don’t know.

Tug McGraw holds up the Daily News during the World Series parade. Photograph courtesy the Phillies

The view from Broad Street during the World Series parade. Photograph courtesy the Phillies

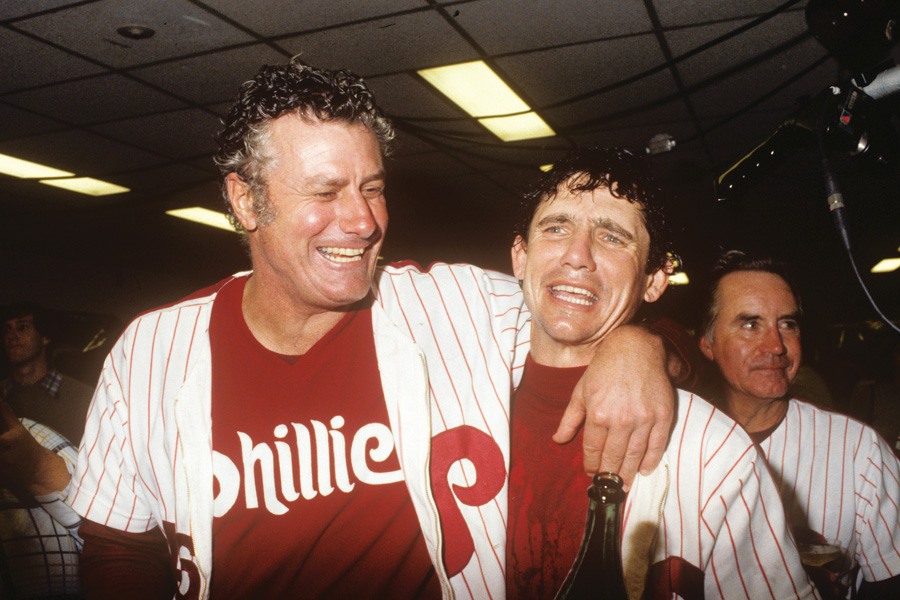

Dallas Green and Larry Bowa let a world championship soak in. Photograph courtesy the Phillies

Middleton: My father and I came out of the subway, and people on Broad Street were climbing lampposts: It was pandemonium, in a positive sense. They were incredulous. It was like New Year’s Eve. I likened it to running with the bulls in Pamplona, which I’ve done. … We were now in the midst of tens of thousands of people healing, in a way.

Schmidt: I felt like a bubble burst. I felt like after that, it became much more fun.

Published as “A City on Its Ass, a Team on Top” in the October 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.