Now It Can Be Told: Karen Hepp Opens Up About Her Battle With Facebook

The Fox 29 anchor graces Philly TV screens every weekday morning. But on the internet, her face has popped up without her permission in Facebook ads for dating sites and other unseemly places. Now the Main Line mom is fighting back — and her case could go all the way to the Supreme Court.

Fox 29 news anchor Karen Hepp is fighting back against Facebook. / Photograph by Emily Assiran

As best as Karen Hepp can remember, Steve Keeley was the first to see it. You know Steve Keeley: He’s the perpetually tanned, square-jawed Fox 29 breaking-news reporter whose most memorable moment at the station may have been when he was almost run over by a snowplow while covering a local 2014 snowstorm. The video went viral.

But the Keeley moment that sticks in Hepp’s mind is from 2018, eight years after she joined Fox 29, where she co-anchors the earliest morning broadcast, the 4-to-6 a.m. show, and later joins Alex Holley and Mike Jerrick for the 9 a.m. slot. According to Hepp, Keeley was scrolling around on his cluttered Facebook feed when an image jumped out at him. It was Karen Hepp’s photo … in an ad for a dating app.

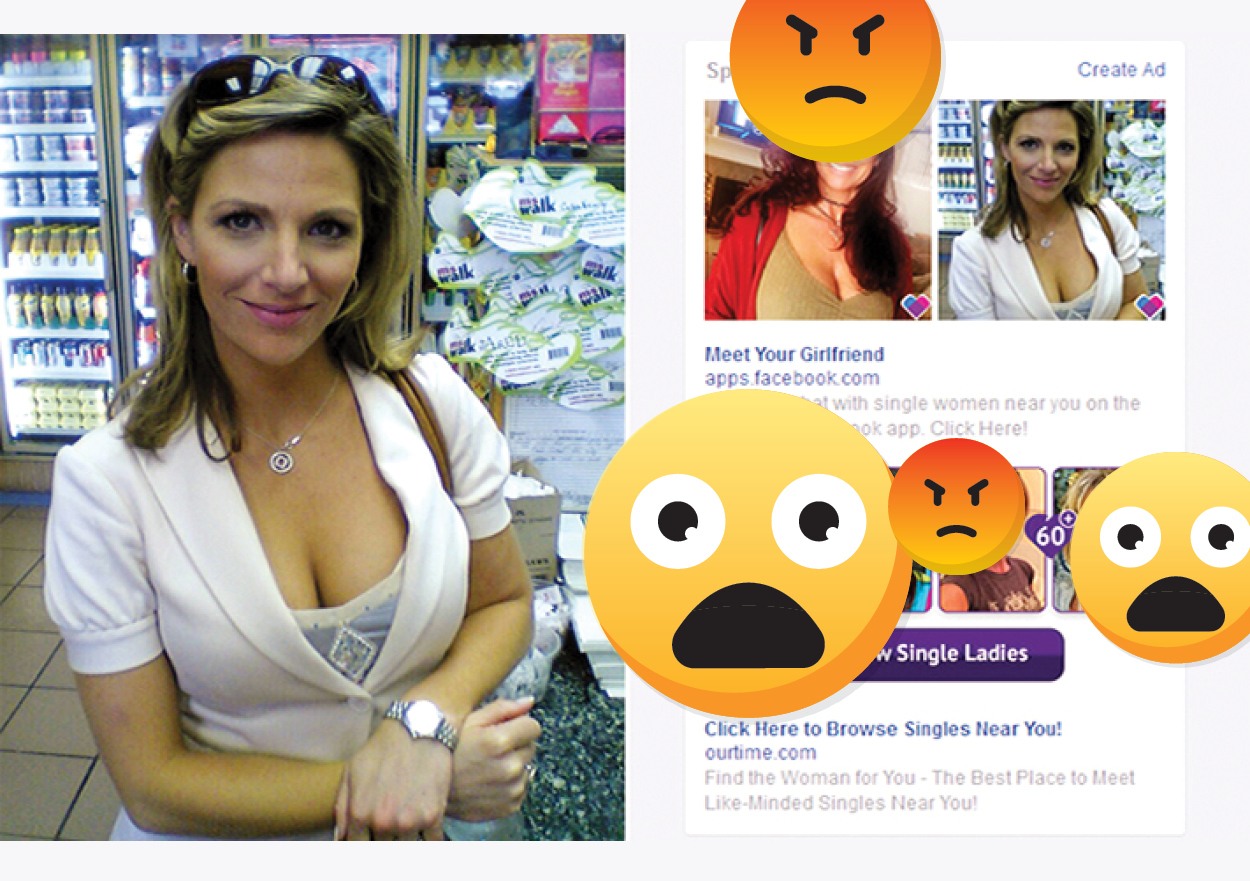

“Meet your girlfriend,” read the ad, just below Hepp’s smiling face and a bit more cleavage than she shows on the morning news. There was no mistaking that it was Hepp. Keeley had been interacting with her five days a week for years. “View Single Ladies,” the button at the bottom of the ad coaxed the viewer. Another colleague happened to see a similar ad.

Naturally, word got around the station. Gossiping about co-workers is standard operating procedure in almost any workplace. But Fox 29 isn’t any workplace. It’s a news station. And as we all know, local TV news personalities are pretty much the only non-sport celebrities in Philly. The secret didn’t stay a secret long.

“Everybody at work knew about it,” Hepp says. “Usually, the last people you want to find out about something like this are the people you work with.”

Eventually, a Fox 29 manager called Hepp into a conference room with a deeply concerned look on his face.

“It was so embarrassing,” Hepp says. “When that happens, you think you’re in trouble. You think to yourself, ‘What did I do?’ And then it’s just… ‘Why am I in these dating ads!?!’”

But it wasn’t just ads for dating sites. Those were bad enough, especially considering that Hepp is a very happily married mother of three — a fact that’s a big part of her professional brand. The photo turned up in other places, some of which were uncovered by investigators at Fox’s corporate office in New York City.

An exhibit from the Karen Hepp lawsuit against Facebook showing the photo and the ad at the center of the suit (image courtesy Karen Hepp)

It was in an ad for erectile dysfunction treatment. It was in the “MILF” section of image-hosting-and-sharing service Imgur. It appeared in a subreddit called OBSF, another not-safe-for-work acronym that stands for — well, you can just google it. And, proving that some people on the internet have way, way, way too much time on their hands, somebody edited the photo to include video of a man masturbating in the background and then uploaded the animated gif to Giphy. Can you imagine?

“I would even get emails from viewers once in a while,” Hepp, 51, recalls. “‘Did you know your picture is on this website?!’ I was horrified.”

She says that after getting nowhere sending cease-and-desist letters and takedown requests to the internet behemoths involved, she found a lawyer who was willing to go after them for her. So in September 2019, Hepp filed a lawsuit in Philadelphia’s federal court seeking $10 million in damages.

I know what you’re thinking: Good luck with that, Karen. When news of the lawsuit broke, many social media pontificators had the same perspective. Yes, there were supporters who gave Hepp virtual high fives, along with the trolls who come out whenever a local celebrity says anything about anything. But at the end of the day, not too many people seemed to think she had a chance. Though I thought it was an interesting case when I first reported on it, I wasn’t exactly willing to bet on Hepp, either.

But don’t count Karen Hepp out just yet. More than two years and one pandemic later, her case against Facebook is still alive, and it could wind up in the U.S. Supreme Court one day soon. It’s a case that has the potential to fundamentally change the way the internet works at a time when both sides of America’s raging culture wars seem to think business as usual on the internet should change—and when public opinion has never been more stacked against Facebook and its ilk. And all because one Philadelphia woman decided she’d had enough.

This is a story, first and foremost, about a photograph — a two-dimensional still image of a single moment in time. It’s a portrait of a beautiful woman smiling at you from your little screen, beckoning with what might be described as a come-hither look, crying out — judging by how advertisers have used it—Click me! Click me now!

And because this is a story about a photo, we all want to know the same thing: Who took it? Where did it come from? Did a company swipe it from Hepp’s social media? Was it taken by a friend, posted online, and then misappropriated for commercial purposes?

No, insists Hepp. She says she’d never seen that photo in its original form, or any other form, until the ads and other uses were revealed to her by station management. She says she’s never used a dating app, so it’s not like a company pulled her photo from its service to use in an ad.

So how was the photo taken? And how did it make its way into the sordid back channels of the internet? According to Hepp and her attorney, Samuel Fineman, their most educated guess is that the photo was taken without her knowledge by a security camera or other device at a store in New York City. Although she appears to be looking directly into the camera, Hepp is certain she was unaware she was being photographed. And even if she had been aware, that wouldn’t make it fair game to use the shot to sell dates with hot older women or creams and potions promising to boost your manhood.

Based on several factors, Hepp believes the photo originated in a bodega or deli in Manhattan when she was working for Fox 5 in New York City in 2007. After spending her childhood outside Philly in Chester County, Hepp bounced around stations in New York State before coming back to her hometown for the gig at Fox 29.

Hepp was able to narrow down the location and date on the photo a bit more thanks, ironically, to the photo’s aforementioned display of cleavage. “As a woman, you know your body,” she observes, with the slightest chuckle. And because of that, she’s able to date the photo to 2007, soon after the birth of her first son. “That’s not me on a normal day. That was clearly when I was breastfeeding an infant at home.”

Speaking of home, that’s where Hepp agrees to meet me — at her gray Tudor-style house on a tucked-away, foliage-filled lane in affluent Lower Merion in mid-November, to see what she is like on a normal day. As we sit in her living room, her son Quinn, now 15 — the infant she was breastfeeding back then — comes wandering in, sporting a Jalen Hurts jersey a day after the Eagles trounce the Broncos 30-13, and plunks himself down on the couch. When I ask him about the situation his mother finds herself in, he blushes and shrugs. So I quickly change the subject to the kinds of things a high-school freshman might actually be interested in. We have a quick chat about pizza. He tells me about some TikTok influencers he follows. He plays soccer right now at the Haverford School, he says, but is looking forward to trying out for the basketball team. And he explains a current bad haircut: He got a locker-room mullet earlier in the week as part of Spirit Day.

Karen Hepp in her Main Line home. / Photograph by Emily Assiran

Quinn and his mom briefly debate an Eagles stat that Hepp winds up being right about. Then she dashes off to the kitchen because she thinks she smells her homemade chicken soup — yes, she makes her own — scorching. But it’s a false alarm.

“Do you want some chicken noodle soup?” she yells to no one in particular. “I have some banana bread I made last night, too.”

Quinn is the oldest of Hepp’s three children, all boys. There’s also 12-year-old Macklin, named for former Eagles wide receiver Jeremy Maclin, and eight-year-old Kellen, who’s in another room, singing in the background for much of my visit. Then there are the animals that contribute to the home’s persistent cacophony. Hepp asks Macklin to take the family’s excitable rescue mutt, Sarah, for a walk. “She can be a little Cujo at times, but she’s basically okay,” Hepp assures me.

At one point during our living room interview, I ask about the squealing coming from an adjacent room. “Oh, that’s just the guinea pigs,” Hepp explains — Richard and Fluffles. There’s also a mouse: Mackie Mouse. And the family used to have chickens: “But then a neighborhood fox and the hawks had other ideas. It turns out humans aren’t the only ones who think chicken is delicious.”

While Hepp deals with an Amazon delivery, I take a look around. A large deer skull sits on a bookshelf near her diploma from Agnes Irwin; she transferred there from Great Valley High during her sophomore year. (Her mom still lives in the house in rural Charlestown Township where Hepp and her two sisters and brother grew up.) Years ago, Quinn found the deer skull and asked Hepp if he could bring it home and bleach it. Like any cool mom, she said sure.

Near the diploma is a framed photo of her husband, Brian Sullivan — he runs races, including more than 28 marathons, when he’s not working as a wealth adviser — shaking hands with Pope John Paul II in Rome. The photo is a few feet from a two-foot-tall R2-D2 that looks like it hasn’t been used since the last Star Wars movie came out.

As we begin to discuss her case (hold tight, we’re getting to that), a dog’s whining and some cartoonish explosions make it clear that Macklin never took Sarah for that walk; instead, he’s playing video games. Hepp asks Quinn to pick up his brother’s slack.

“My house is overrun with boys,” she shrugs. “And the girl dog.”

This is the Karen Hepp image — the Main Line mom who goes to five of her kids’ games on any given weekend. Who cheers so loudly for the Eagles that she named one of her treasured babies for a player. (Who does that?) Who deals with piles of Amazon boxes, makes chicken soup from scratch, enjoys her glasses of wine, and tries to stay fit doing yoga. Whose professional persona is built around all of this. And whose kids are old enough to be aware of how their mother’s image is being used online. All of which helps explain why Hepp is digging in.

While many (almost all) local news celebrities keep their private lives very private, Hepp is on the opposite end of the spectrum. Her Instagram is filled with photos of her family. She talks about them on the air. It’s real. Viewers love it.

It can be a little harder to identify with Hepp’s colleagues, Mike Jerrick and Alex Holley. We know the roles they play on the air each weekday morning, but who are they really? And who can blame them for being more discreet, with all the trolls and creeps out there, to say nothing of the not-so-glamorous stories that have come out about local TV personalities who weren’t? (Looking at you, John Bolaris.)

But viewers identify with Hepp immediately, in part because she’s very much herself on the air and in part because she’s happy to talk live on TV about Kellen’s efforts making cookies for Santa. She’s an open book. An everywoman. Not the woman those internet companies chose to sell their products. That woman is very much the antithesis of Hepp’s image — an image she desperately wants to protect. It’s her livelihood, after all. Hence the lawsuit.

“This is totally off-brand for me,” Hepp explains. “I’m a regular mom, not some old lady who wants to date you.”

She initially had a hard time finding a lawyer to take the case, which is rather remarkable for a TV news personality in a region known for its lawyers. But suing Facebook for something that, at the end of the day, happens all the time? Estimating conservatively, at least one billion images are shared on the internet daily. Just because one of them happens to wind up in some unsavory places, you’re going to take Facebook to court? It’s not as if the company now calling itself Meta used Hepp’s photo to advertise Facebook. It didn’t stick her photo on a billboard along I-95 proclaiming, “This cougar uses Facebook. So should you.” These ads are all served up by bots and algorithms that you and I will never understand. Hers was for some third-party app and probably appeared on Facebook and a million other places.

But then a Fox 29 colleague told Hepp about Cherry Hill-based attorney Samuel Fineman, who had recently taken on Pornhub after a Marlton man’s face was used in an online gambling ad that appeared on the porn site. The man had shared a photo of himself fanning $100 bills; the photo somehow wound up in the ad, the ad wound up on Pornhub, and the man’s wife got wind of it and was none too happy to see his face next to all those gyrating buttocks. The cases seemed similar enough to Hepp that she gave Fineman a call.

“This abuse is happening all the time,” Fineman tells me. “So I took Karen’s case.”

On September 4, 2019, Fineman went to the federal courthouse at 6th and Market and filed Hepp’s lawsuit against Facebook, Reddit, Imgur, other online entities, and various John Doe defendants, in case, through the discovery process, he’s able to determine who else is responsible for the photo and the ads. (None of the companies in question have publicly commented on the case.)

Fineman and attorneys for Facebook and some of the other companies named in the suit spent much of 2020 working through legal technicalities, filing motions, and conducting conferences on Zoom. Eventually, Facebook did exactly what many armchair legal observers expected it to do: invoked Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, a law you may never have heard of that has a huge impact on the internet as we know it today.

In olden times, before the beast known as the internet dominated every second of our lives, people got the news and information they needed or wanted through books, magazines and newspapers—actual paper with words printed on it. Those books, magazines and newspapers were the products of publishers, who were responsible for their content. Even the ads were reviewed by real live human beings.

There were checks. There were balances. There were processes, protocols and procedures. When a publisher got something wrong, lawsuits ensued. It was easy to figure out whom to sue, because if the offending ad appeared in, say, the Inquirer or this magazine, it was the Inquirer’s or this magazine’s fault. And publishers were very, very careful, particularly in Pennsylvania, where juries are famous for coming down hard on companies that publish libelous, defamatory or otherwise harmful content. Consider famed attorney Richard Sprague’s 1973 lawsuit against the Inquirer that initially resulted in a $34 million award against the paper.

But then came the internet. Early internet service providers like CompuServe and Prodigy faced lawsuits over user-generated content found in their various portals. And other companies worried that they, too, might be held liable for information customers were getting from them, even though it wasn’t really from them.

The analogy of a bookstore illustrates this relationship. A bookstore might sell a magazine, and that magazine might contain defamatory content, but you wouldn’t sue the bookstore for selling the magazine, right? A bookstore owner can’t possibly be expected to read every page of every magazine and book on offer to make sure it passes legal muster. Multiply that single bookstore’s volume out by, oh, a few million zillion, and you have the content of the internet.

In an effort to give the internet room to grow without online companies worrying about being sued left and right, Congress passed Section 230. The general idea is that an online company is immune from liability so long as it’s simply distributing content produced by others. Section 230 makes a clear distinction between publisher and distributor, and analysts today say the internet might never have taken off if it hadn’t been signed into law. There might not be an Instagram, an Amazon, a Pornhub.

The dating-app ad on Facebook that bore Hepp’s image clearly wasn’t for Facebook’s own dating service. Facebook was merely hosting an ad produced by somebody else — one that likely wound up there without any living entity at Facebook or any company hired by Facebook ever seeing it. That’s just the way it works. Given all that, Hepp would appear not to have a case, right? Not so fast. Here’s where it gets interesting.

Section 230 does have some exceptions, but only a few. The exception that Fineman argues applies to Hepp is one regarding intellectual property rights. When we talk about intellectual property, we’re usually referring to federal protections like copyrights, trademarks or patents. Section 230 makes it quite clear that an online company can’t claim immunity when the issue in dispute is one of those.

But there’s also something known as the “right of publicity.” And it’s absolutely impossible to understand Hepp’s case — or why she might win — without understanding this concept.

Unlike the federal protections mentioned previously, the right of publicity is a state-level legal concept designed to prevent a person or company from using your name, your photo, or anything else about you that makes you distinctly you to sell a product or service without your permission. Just over half of the states have a right of publicity on the books, and Pennsylvania is among them. A company can’t hijack someone’s “image” or “likeness” for its commercial benefit. You can’t open a cheesesteak joint called Big Willie’s Beef with a giant neon-lit image of Will Smith chowing down on a greasy whiz-wit without first obtaining Will Smith’s permission, which he might grant you … if you cut him a huge check.

Though it’s illegal, this kind of thing happens all the time. Scrolling through my own little social media vacuum as I write this, I see countless examples, from local DJs advertising “Taylor Swift nights” using not just Taylor Swift’s name but also her photo, to the head shop that I’m pretty sure doesn’t have Adele’s permission to use her pic to sell its products using the title of her song “Rolling in the Deep.” Cute, but against the law.

In Pennsylvania, we have a right of publicity even after we’re dead. (You can thank Elvis Presley’s manager along with Bela Lugosi’s son, who, realizing the potential posthumous value of memorabilia, lobbied to update the law, eventually convincing Tennessee and California legislatures, respectively, to do just that. Other states followed, with New York adding a postmortem right of publicity last year.) And right of publicity doesn’t just apply to celebrities. Of course, average people aren’t likely to win huge damages in right-of-publicity cases, because their overall images wouldn’t be deemed particularly valuable, since most of us don’t monetize our likenesses.

But as Hepp points out to me in her living room, there are a whole lot more people these days who are monetizing their images compared to just five or 10 years ago. “You can show people how to do makeup on TikTok and get 10 million followers,” she says. “Instant celebrity.”

The idea of a right of publicity dates back to the mid-to-late 1800s, according to Penn legal scholar Jennifer E. Rothman, the nation’s leading expert on the subject. “The origins of right of publicity actually overlap with Hepp’s case, because what people were complaining about back then was the emergence of instantaneous photography and the ability of non-professional photographers to snap a photo of a person on the street without that person’s consent and often without their even knowing,” she explains. “All of a sudden, people’s images were being taken and used in ways they didn’t like.”

One of the biggest right-of-publicity cases in modern history concerned basketball legend Michael Jordan, who sued a large grocery-store chain that used his name, image and jersey number to advertise its stores and push steak coupons. A jury awarded Jordan $8.9 million after he testified that he doesn’t do any kind of endorsement deal for south of $10 million.

Right of publicity can even extend to one’s voice. In the 1980s, Ford Motor Company asked Bette Midler, whose voice is more distinctive than most, to sing a modified version of one of her hits in a commercial for the Mercury Sable. When she declined, Ford asked another singer — one whose voice was amazingly similar to Midler’s, and who happened to be one of Midler’s own backup singers — to perform it. She did. Midler sued Ford and walked away with $400,000.

Then there was Tom Waits, possibly the last person you think of when you think of Doritos. Yet Doritos used a sound-alike of Waits — another singer whose voice a fan could pick out immediately — to advertise the chips. Waits sued. Waits won.

“Waits and Midler both had strong views that were less about the market and more about their dignity,” says Rothman. “They don’t really do advertising.”

All of these cases are pretty clear. The grocery store took one of the world’s most famous people and used his face to sell meat. Ford and Doritos tried to trick listeners into believing that actual celebrities were endorsing their products. Game over.

For Hepp, because of the nature of her suit and the possible immunity provided by Section 230, liability comes down to whether a state-based claim of right of publicity can be lumped in, legally, with protections like trademark, patents and copyright.

Even though right of publicity is a state law, Hepp — like others before her — is able to sue in federal court because the entities involved are located in different states. That’s how federal court works.

Lawyers representing the online companies argued that Hepp has no claim because of Section 230’s protections, and in 2020, Judge John Milton Younge sided with Facebook and threw out the case without even hearing oral arguments. In his view, Section 230’s intellectual property exemption didn’t include Hepp’s right-of-publicity claim.

Many observers thought that decision would be the end of Hepp’s case. Facebook has all the legal resources in the world. Hepp has Fineman. “This is truly David meets Goliath,” Fineman observes. “On one hand, you have Facebook. And on the other hand, you have Karen and my firm, which is literally me and my wife. We are two people. That’s it.”

Fineman filed an appeal with the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers all the federal courts in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware. Last September, after hearing oral arguments from Fineman and an attorney representing Facebook, the appeals court decided Judge Younge was wrong to toss Hepp’s case. Facebook quickly filed a motion for the appeals court to reconsider that decision, but the court declined. Its ruling in favor of Hepp stands.

This doesn’t mean Hepp won her lawsuit. Far from it. It just means her case can’t be thrown out right now on a Section 230 technicality.

The appeals court decision caused a bit of a stir because it created a legal inconsistency in the federal court system. In a separate case, a different federal appeals court recently ruled the opposite way, holding that right-of-publicity claims aren’t covered by the intellectual property exclusion in Section 230 — and unlike state-level laws, which can and do have their own procedures and rules, federal laws must be administered consistently and uniformly. That could very well mean the U.S. Supreme Court may decide the matter, as Facebook is expected to ask the high court to do very soon.

The Supreme Court could agree to take the case and put a pause on Hepp’s lawsuit in Philadelphia. Another possibility is that it could do nothing and let the case proceed to trial in Philadelphia. Whatever happens, legal scholars and intellectual-property lawyers across the country will be paying close attention.

“I certainly am not going to go on the record with a prediction as to what the Supreme Court will do in this case,” says Penn’s Rothman. “But this has a better chance of getting in front of the Supreme Court than many right-of-publicity cases, because we have a clear circuit split surrounding an issue that affects the functioning of the internet and social media. I certainly wouldn’t be surprised if this is the right-of-publicity case that gets decided by the Supreme Court.”

Hepp’s lawsuit couldn’t have come at a more interesting time, and that timing may work in her favor. Section 230 has recently become increasingly controversial. And it’s not just one side of the culture wars that has concerns about it.

Both former president Donald Trump and New York U.S. Rep Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have said it’s time to reform Section 230 (likely the only thing they agree on), though in different ways. Trump has blamed Section 230 for Twitter’s censorship of him; when he was president, he vetoed a $740 billion defense bill in revenge against Congress for not repealing it. AOC has suggested that Section 230’s protections allow Facebook and other online platforms to spread dangerous misinformation.

In 2021, cultural economist and software developer Steve Waldman, once a fervent supporter of Section 230, wrote an op-ed in the Atlantic arguing that it has “ruined the internet.” He pointed out that the law was drafted at a time when “the possibility that monopolies could emerge on the internet seemed ludicrous.” That served a purpose in 1996, but now, more than 25 years later, the world and the internet are completely different places.

Section 230 has, in fact, been reformed in recent years. In 2018, Congress amended it with the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, or SESTA, which prevents “escort” websites like Backpage from saying, “Oh hey, we just host these” about ads for women who are victims of sex traffickers. Backpage.com raked in about half a billion dollars before SESTA went into effect. Where is the site today? It’s gone. Poof. Just like Craigslist’s enormously lucrative escort-ad section.

So change to Section 230 is possible. And while the law has sparked controversy, that’s absolutely nothing compared to the shitstorm that Hepp’s main defendant, Facebook, now finds itself in.

Plenty of people didn’t like Facebook back in 2019, when Hepp filed her suit. Now, two and a half years later, the company is a downright pariah. Hepp may not win in federal court. But in the court of public opinion, she’s already the victor.

“I know I am probably never going to earn any money from this lawsuit,” Hepp tells me in her living room. “But I’m never going to stop fighting.” To her, the fight is what’s important, not the outcome. “It’s just the right thing to do,” she says. “The best thing I can possibly teach my kids is to stand up for what you believe is right, even if it’s a long, tough fight to get there. And even if you think you can’t win.”

Published as “Karen Hepp Vs. Facebook” in the February 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.