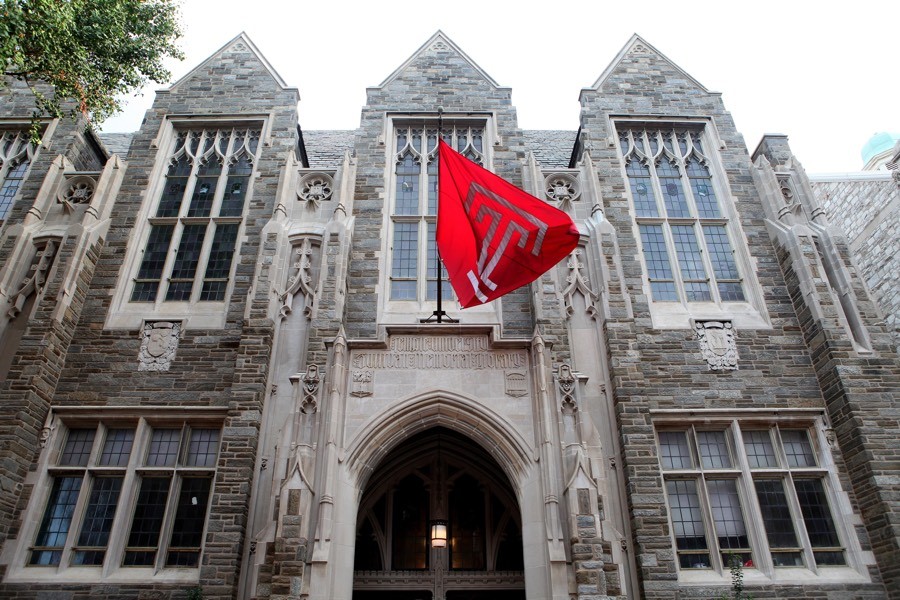

Temple Faculty Union Demands Right to Teach Online This Fall

With 92 percent approval, the union issued a list of demands — chief among them the guaranteed right to opt out of in-person teaching this fall. The Temple admin says that's not the majority staff opinion.

The faculty union at Temple doesn’t want to teach in-person classes this fall semester. Photo By Raymond Boyd/Getty Images.

The other week, we told you about the simmering discontent among professors at some Philly colleges, as their institutions sought to return to on-campus instruction during the coming fall semester. At Temple, that professorial anger has now reached a full boil. The Temple Association of University Professionals (TAUP), the union that represents tenure- and non-tenure-track faculty, adjuncts, and other academic professionals like librarians, voted on Thursday to issue a list of demands to the administration. Those demands include things like guaranteeing all Temple students and staff receive high-quality fitted face masks and providing free health care to any employee forced to work on campus in the fall. But the main insistence is simpler: that no professor, whether tenured or adjunct, be forced to teach in-person classes this fall.

When we last wrote about this, a Temple spokesperson told us in a statement that the school had “worked with faculty and staff to make accommodations when needed, and will continue to do so.” But at a press conference on Thursday, members of TAUP said that wasn’t always happening. Union president Steve Newman, a professor of English, said that of the TAUP members he’s heard from, around 10 percent have requested exemptions but have yet to get a response from Temple and are still slated to teach classes in person. Ray Betzner, a spokesperson for the university, said the exemptions for that 10 percent were likely still in the process of being processed.

Still, TAUP believes there shouldn’t be any reason for widespread exemptions in the first place. Absent a legal reason, like curricular requirements for programs that might require some in-person instruction, the union says there shouldn’t be a classroom component to the fall semester. “That’s why we’re demanding this for the safety of our members and students,” Newman said.

Of course from the administration’s perspective, there is another reason for teaching courses in person. In-person courses means students in dorm rooms on campus. And students on campus means the administration can make a stronger case that tuition should remain the same — even though it’s abundantly clear to everyone that the college experience this fall is going to be anything but normal. Temple has said it plans to cut in-person classroom space by 80 percent, from more than 15,000 seats to 3,000. Freshmen and seniors for will have priority for much of the in-person space that’s left.

Still, for a school with nearly 30,000 undergrads, that’s a lot of in-person instruction. Multiple TAUP members on Thursday suggested that Temple’s emphasis on this freshman and senior “experience” is dictating which classes end up being taught in person, rather than pedagogical reasons. Newman noted that for some gen eds — standard lecture format courses that should can be most easily replicated online — many sections are currently scheduled in person. Susan Dickey, a professor of nursing, said she knew of a colleague in her 60s who was baffled upon finding out her writing seminar was to be taught in person. “There’s no reason that cannot be taught online,” said Dickey.

The pressure is even more acute, TAUP members said, for Temple’s 1,500 part-time adjunct instructors, who have little job security and teach semester to semester. That precarity makes adjuncts less likely to speak out about their fears of unsafe working conditions, said Carol Gallo, an adjunct in the College of Liberal Arts. And then there’s the secondary pressure on adjuncts to not turn down work — if they refuse to teach in person, they won’t be eligible for unemployment benefits. In effect, the decision is: Teach in person and risk getting sick, or turn down the teaching gig and receive no income at all. “It’s like a sweat shop,” said Tyler School of Art adjunct Jennie Shanker. (Betzner’s statement noted that the city Department of Health approved Temple’s reopening plans this past week.)

TAUP made the decision to issue its demands after soliciting a vote from its dues-paying membership — 1,075 people out of the 2,400 total staffers the union represents. TAUP received votes from 50 percent of the eligible group, with 92 percent voting in favor of the demands.

The Temple administration believes the union’s gripes are that of a vocal minority. “The results of this vote do not come close to representing a majority of faculty views,” Betzner wrote in a statement. The total number of faculty and adjuncts at the university is 3,900, Betzner said. He claimed that “with the exception of TAUP,” the university has had positive relationships and cooperation with other employee unions. (In our prior story, though, at least one other union, that of Temple’s grad students, was also extremely displeased with the administration.)

At any rate, Betzner emphasized that “should circumstances warrant, we are prepared to adjust our plans as needed.” Multiple TAUP members said they found that hard to believe, considering the university has not apparently set a specific benchmark of coronavirus cases on campus for when it would consider canceling the in-person semester. Betzner says the university is in frequent conversation with local and state health officials and that decisions to modify plans would come on their recommendation of what’s safe.

This isn’t an intellectual exercise anymore. The Los Angeles Times reported just yesterday on an outbreak of 40 cases on USC’s fraternity row. That school hasn’t completely given up on in-person learning yet, but you don’t have to look very far — in fact you can look right here in Philly, to the School District, which recently abandoned its in-person plans until at least mid-November — to realize that there is a tide of reconsideration, and it’s not flowing in the direction of the classroom setting.

“What we’re really trying to do is to get Temple to listen to the facts and actually change things,” said Shanker. And what if they don’t? On that subject, the union was coy — except to say that their next action would be more aggressive than a demand letter. “If they don’t act on it,” Shanker said of the demands, “we do have to escalate. What choice do we have? This is too important.”