Political Scientist Daniel Q. Gillion on What Makes Protest Movements Effective

Philly has had large and contentious protests, yet the Mayor's proposed reforms are less radical than those considered in other cities. Penn professor Daniel Q. Gillion explains why that's not necessarily the end of the story.

Demonstrators rally at the Art Museum at one of the protests in Philadelphia in early June. Photo by Cory Clark/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

How does a protest movement translate demands into political action? This is a relevant question for the millions of Americans who have spent the past month protesting police violence and the murder of George Floyd and other Black Americans. While some of the calls from activists have included moderate reforms like banning chokeholds, the prevailing demand is for something more extreme: defunding of police departments, or even abolishing them altogether. Some cities, like Minneapolis, have responded with swift and radical action. Others, less so.

In Philly, site of some of the largest and most contentious protests in the country, Mayor Jim Kenney has resisted the calls for defunding police. Instead, he has proposed a list of reforms — increasing police oversight, changing use-of-force protocols — that might have satisfied demonstrators in years past but now clearly seem to fall short.

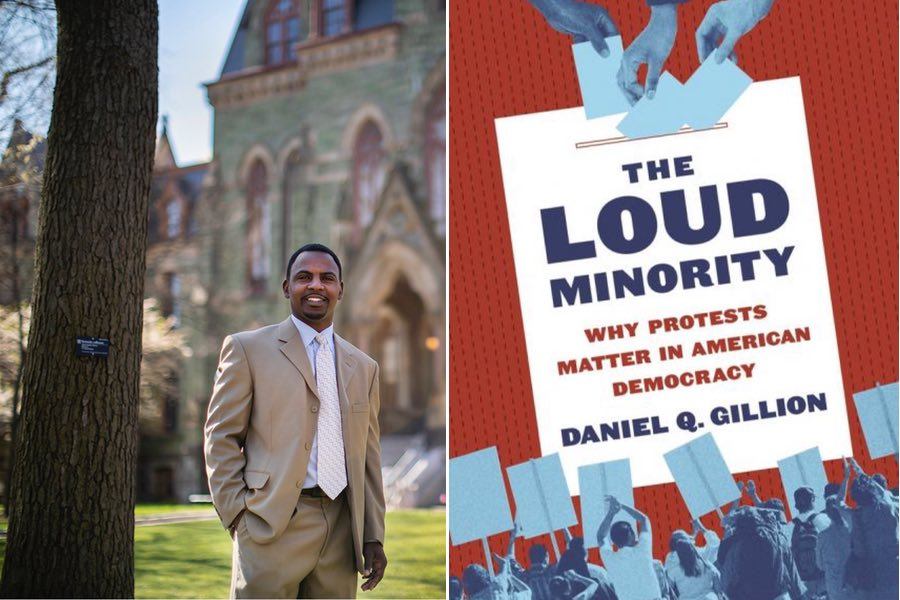

Daniel Q. Gillion, a political science professor at Penn who has written multiple books about how protest informs politicians and prompts action, says Kenney’s present opinion shouldn’t necessarily be understood as his final stance on police reform. The political response to mass movements is slow and far from over, Gillion says. He spoke with Philly Mag about that process, the sudden shift in public opinion on Black Lives Matter, and why riots can sometimes produce quicker change than peaceful protest.

Let’s start with a very basic question: When you look at a protest movement, how do you grade its success?

Looking at the success of the movement is very complicated, because it involves multiple parts — some that are sociological, some that are political. When you look at any given movement, we can see policy changes taking place in government at the local level and at the federal level, but we can also see individuals changing the way they see a particular issue. Public opinion can change — the way that we treat one another, the way that we talk to one another. And in my book, all of those changes come together to represent the overall effect of political protest and social movements in society.

The effectiveness of protest has been thought of as tied to media coverage. Philadelphia saw tear-gassing of demonstrators, which produced one of the more visceral images of police brutality in response to the protests. When we talk about the policy component of the response, though, other cities like Los Angeles and New York City have actually defunded their police budgets to some extent. Minneapolis voted to disband its force. Philadelphia hasn’t actually decreased its police funding. Considering the extensive media coverage and outrage over the tear-gassing, why didn’t Philadelphia see a more stark policy response?

The verdict is still out. Oftentimes when we see a response, we think that’s the end-all, be-all. If we’re looking at Philadelphia, the way that they’ve addressed policing and police funding has been a little slower than other cities. But what we have seen is an acknowledgement of wrongdoing when the video appeared that showed police were tear-gassing individuals and boxing them in on I-676. They recognized that they were in the wrong, and they addressed that issue. I think that as we move closer to the elections, we will see more attention on this particular issue. It might come in the form of complete radical reform in policing. It might be the changing of the guard with those who oversee the police department. We can expect to see changes in multiple ways, but I think it might be too early for us to say that Philadelphia is not on the same level playing field as some of these other cities.

Do you think some of this comes down to the unpredictability or maybe the intractability of political figures in charge of any city?

Protest has the ability to persuade those individuals who are most sympathetic to the concerns and issues of protesters. So if you have liberal protests, as we’ve seen with the George Floyd protests, they have the ability to influence liberal politicians, who are often Democrats. Which means that if you’re looking at the people in power in Philadelphia, it might be able to persuade these individuals to move in a direction that supports protesters. It will take time, but it also might take a changing of those politicians in office. The political ideology and the political leaning of politicians in office is vital to whether or not policy is passed.

Daniel Q. Gillion’s latest book is The Loud Minority: Why Protests Matter In American Democracy. Photo by Eric Sucar. Book jacket courtesy Princeton University Press.

There has been a massive shift just recently in public opinion — according to the Times, there is a net support for Black Lives Matter of plus 28 percent, compared to minus four percent just a year ago. Seventy-six percent of Americans now also report that they consider racism and discrimination a “big problem,” up 26 percent from 2015. Typically, we think of America as polarized, without much movement in public opinion. What is it about policing that has been the exception to that general rule?

In 2016, there was a negative sentiment for Black Lives Matter to the point that some conservatives said the statement itself was racist. It’s sort of baffling to look back at that moment. What is there about policing that allows individuals to garner buy-in? I don’t know if it is policing per se. Rather, it’s the constant pushback on policing over time. I always like to say that the George Floyd protest isn’t a catalyst but rather a crescendo of individuals constantly pushing back. Now, what the George Floyd video does do is make it very real for individuals who might have doubted or questioned that this sort of injustice was taking place in communities. And to be quite sure, it’s not the first video that individuals have seen on this sort of injustice. Actually, in the Black community, these videos are constantly produced. And it’s heart-wrenching to watch this. But that’s the reality. And that’s where you get your buy-in. You get your buy-in from individuals sitting down, coming to terms with the realization of America.

In your book The Political Power of Protest, you mention that in 1963, race relations had become the most important problem facing the country. Fifty-two percent of Americans said that should be the government’s number one priority. Whereas just eight percent had given that answer a year before. What parallels do you see between these two moments in terms of sudden shift in public opinion?

Whenever we have a major discussion of race in government, or the public seeing race as a vital issue, protest on race is often in the background. And that’s important, because protest has this ability to put the issue of race on the public agenda. We saw this in the early 1960s with the civil rights movement — protests in Selma and at Birmingham. These protests allowed the American people to stop and realize there were injustices taking place in the Black community. We’re seeing a similar thing take place today. Protests that are very contentious, very raw, very real, and that are occurring in every corner of America are forcing individuals throughout the nation to say this is an important concern. Public opinion changes when protests occur — especially along the lines of race. That change in public opinion provides the fuel that is needed for politicians to revisit this issue and to put forward policies that address the concerns of protesters and address the concerns of many in society.

Another parallel between the present moment and the ’60s is the conversation around so-called violent acts of rioting. Omar Wasow, a politics professor at Princeton, found in a recent study that in areas where there were violent protests, people voted disproportionately for Nixon in 1968. There were episodes of “violent” protests this time around, but we’re still seeing massive positive swings in public opinion for Black Lives Matter. Does that disprove the notion that violence might push more moderate people away from the message?

When you consider violence, we have to realize that violence in protest occurs on both sides. You have the disgruntled, agitated rioter who is engaging in violent action, but you also have police officers who are putting out tear gas and shooting rubber bullets at peaceful protesters. If you look at the 1960s, even in 1968, it is the case that Nixon was able to win that election. However, if you look at protest in various local communities — because I believe that protests have a very localized effect — the more violent that protests became, the more likely it was to help the individuals who were favorable to protest get into office. And if you’re looking at 1968, even though Nixon won the presidency, Democrats were able to retain control of the House and the Senate. For various Congressional races, the more protests that occurred in a specific Congressional district, the more likely it was that Democratic candidates, who were more sympathetic to protesters during that time, would receive a greater share of the two-party vote. This goes back to my point about the impact of protest. Protests have a multi-faceted impact on society and all politics. We cannot take a narrow view of the impact of protests. Focusing in on just a presidential election is a narrow view.

The protests are still ongoing in Philadelphia, although they’re smaller than before, which I guess in some ways is the natural cycle of things. Specifically in the Philadelphia context, what do you think happens next? And from the activists’ perspective, how does one prevent this issue from fading away and not just ending at the list of reforms that Kenney has proposed so far?

The way that you keep the movement going on is to continue to engage in peaceful protest activism. It is to continue to keep these issues on the agenda. There’s no doubt that politicians are persuaded by those protest activities and the concerns voiced in protests. So if you examine how Kenney has responded to this movement, for sure he has been attuned to the protest, to their concerns. As the movement persists, I think that his policies on this issue will evolve to be even more sympathetic and more conscientious of the concerns that individuals are voicing. What exactly that will translate into — if we’re looking at defunding more police or changes in policing — I think it will take many forms.