Coronavirus Could Put a $650 Million Hole in Philly’s Budget. Here Are Four Takeaways

A new report from City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart makes one thing clear: Philly is about to have much less money than it expected. What it means for dining, retail, tax reform, and the already-contentious relationship between the controller and the Mayor.

A new report from City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart says coronavirus is about to leave a big hole in Mayor Jim Kenney’s budget. L: Photo by Matt Rourke/AP. R: Courtesy photo.

The past decade has been a good time to be a public official who likes spending taxpayer dollars. This is because there have been lots of taxpayer dollars to spend! Adjusting for inflation, the City of Philadelphia’s expenditures increased 27 percent from 2010 to 2019. And while, yes, it’s true other cities like Houston and Seattle had even greater increases in spending, the fact is, Mayor Jim Kenney in the past few years has still been able to increase spending almost across the board. His latest budget proposal, unveiled in early March, totaled $5.2 billion. Last year, he even established a rainy day fund worth $30 million.

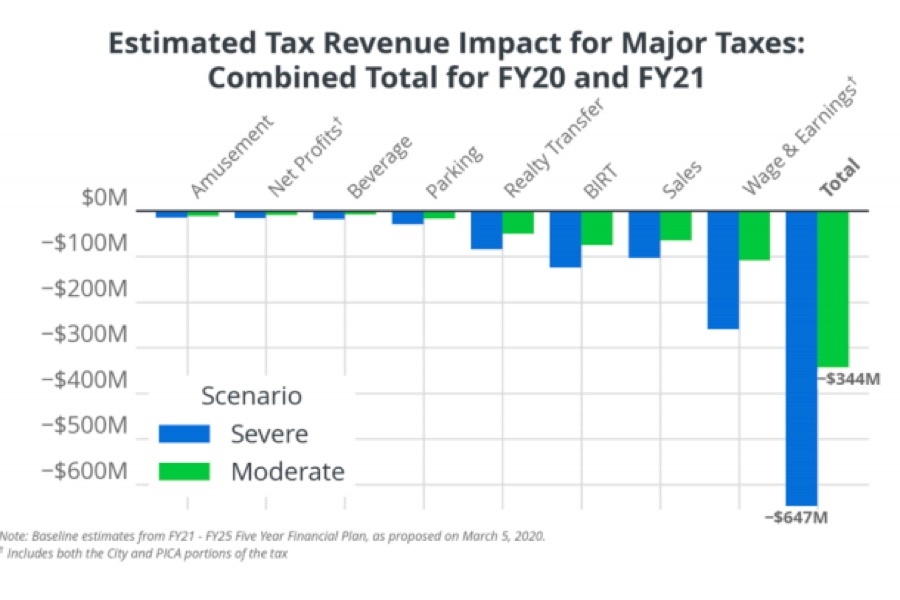

So much for all that. The coronavirus has brought with it an economic upheaval — some 26 million unemployment claims nationwide — unmatched in decades. We’re only just starting to get a picture of how acutely local governments will be impacted by the downturn, but on Monday, City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart gave us a clue. Philly government, according to a report by Rhynhart’s office, could lose anywhere from $344 million to $647 million in tax revenue by fiscal year 2021, which ends in June of next year. In other words: That rainy day fund is starting to look a lot more like a shallow, dry well.

Here are four other takeaways from the report.

Excerpt from the city controller’s report.

The Source of Tax Dollars Matters

In the report, Rhynhart breaks down how the city’s various sources of revenue might be impacted in the future. The wage tax — the city’s single largest source of revenue, at roughly $1.6 billion, or 40 percent of the city’s general fund budget — is facing losses of more than $100 million by the end of fiscal year 2021. That’s under a “moderate” COVID-19 impact scenario, where the economy experiences a short six-month downturn followed by a quick rebound. In the “severe” scenario, where social distancing continues into June and hinders a speedy economic reboot, Rhynhart suggests wage tax revenues could drop nearly $160 million — or 7 percent.

Other revenue sources face similar steep drops. Rhynhart estimates business income taxes could decline $121 million between now and the end of the next fiscal year. The same goes for sales tax, which might face a reduction between $50 million and $104 million.

Philly is far from unique here. Every city and state in the country is dealing with some amount of budget contraction. Pennsylvania could face a budget shortfall between $2.7 billion and $3.7 billion over the next 15 months. The state has already stopped paying 9,000 employees. New York City, meanwhile, expects a 3.5 percent drop in tax revenue, equaling $2.2 billion, over the final months of fiscal year 2020.

Both a city’s economic makeup and its tax structure determine how it will be affected by a sudden economic downturn. “The structure of the local economy is a real variable, and the more cities are single industry dependent, the more challenged they are,” explains Center City District head Paul Levy, who has also been a longtime advocate for tax reform in Philly. Cities that are reliant on now-evaporated tourism revenue, for instance, like Orlando and Las Vegas, are even worse off than Philly.

But if Philly’s economy is diversified, its tax revenue streams are less insulated. Why? Because the city heavily relies on a wage tax — and when many people suddenly do not have wages to be taxed, that’s a problem. Compare that to property taxes, which are determined well in advance, and therefore less volatile in the short-term. (Also, unlike workers, buildings do not move, which makes them a more reliable source of tax dollars.)

The upshot is that a city like Boston, which generates some 70 percent of its revenue from property taxes, faces less of an immediate budget crunch than Philly.

Rhynhart Doesn’t Expect Much Future Revenue From Restaurants

Midway through the report, Rhynhart outlines the anticipated reduction in tax revenues, broken down by sector of the economy. No great surprise: Restaurants, retail and hospitality are all facing the biggest disruptions.

More revealing are Rhynhart’s estimates of how long the damage will last. In the severe COVID disruption scenario, Rhynhart estimates that wage taxes from restaurant workers could decrease 90 percent in the short term. A year from now, wage tax revenue from restaurant workers could still be a full 23 percent below pre-COVID levels, suggesting something that many restaurateurs already fear: Many smaller restaurants simply may not be able to reopen even after the government eases social distancing guidelines.

Philly’s estimated decline in wage tax revenue, broken down by industry.

The story is similar for other industries. In Rhynhart’s “moderate” scenario, retail might generate 50 percent less sales tax in the final quarter of this fiscal year. One bit of good news: Under that same scenario, the report suggests that sales tax revenue might be just 5 percent lower than usual a year from now.

Levy notes that the local economy may be less susceptible to prolonged downturn because two of its pillar industries — healthcare and higher education — can continue operating during the pandemic. But the possible permanent loss of jobs in the restaurant and service sectors, Levy adds, doesn’t bode well for a city that has the highest poverty rate among America’s 10 biggest cities and needs a robust entry-level job market.

The Kenney Administration Is Not Happy

You can forgive the Kenney administration, which is now facing a gigantic hole in its budget, for being a bit cranky. Still, it was a tad surprising to see the administration bickering in the press over Rhynhart’s report. In the Inquirer, Rhynhart suggested Kenney may need to cut some of his priorities, in order to make up for the impending budget hole. To which city spokesperson Mike Dunn responded: Rhynhart “seems much more concerned with generating press as opposed to governing.”

Then again, given what we know about the relationship between Rhynhart and Kenney, maybe it wasn’t so surprising after all.

A Shot at Tax Reform Post-COVID?

Paul Levy has been beating the tax reform drum for a while. Following the 2008 recession, he advocated a change to the Pennsylvania constitution, which would have allowed the city to increase the rate of property taxes on businesses, and therefore decrease its reliance on the wage tax. That effort failed.

Earlier this year, before the COVID crisis began, Levy had another proposal: Decreasing the tax rate of the wage tax and the business income tax. (The city has been doing this, but at a slower rate than Levy would like.) Levy’s view was that a lower wage tax would actually spur more business growth in the city and increase the population, both of which would eventually offset the loss in revenue from the wage tax. Levy figured now was the right time to lower the tax, since Philly’s budget was growing every year.

Coronavirus has now thrown a wrench into those plans. “It’s like an earthquake right now,” Levy says. “You don’t have the stable ground to make really definitive suggestions long term.” But out of the crisis might be a new opportunity to consider the sorts of tax reforms that make Philadelphia’s source of income more stable.

When that time comes around, in the next few months, “we need to put everything on the table,” Levy says. “This is a moment for strategic rethinking.”