Tom Wolf’s Leadership Style Was Made for This Moment

He’s infuriated some of his critics on the right, but Pennsylvania’s deliberate, reasonable governor is providing calm in the middle of this storm.

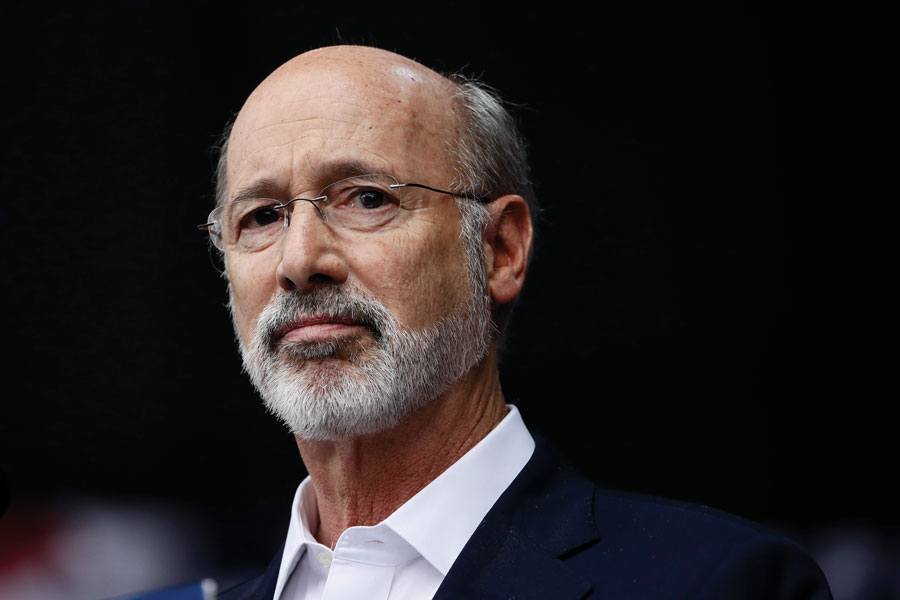

Tom Wolf’s coronavirus response shows how the governor was made for this moment. Photograph by Matt Rourke/Associated Press

Governors are having a moment.

Andrew Cuomo, most apparently: New York’s governor has been blunt and forceful, pushing, cajoling and even praising the President on CNN, his desperation for his state abundantly clear. Also Phil Murphy of New Jersey, stepping up with daily briefings on the spread of COVID-19 when he should be recovering from surgery for liver cancer. And “that woman from Michigan,” otherwise known as Gretchen Whitmer, who failed to appreciate our President as she demanded help from the feds in getting medical supplies for her state.

In a somewhat different manner, Pennsylvania’s governor has stepped up, too. Tom Wolf has delivered a series of directives almost like fireside chats — some of them while wearing a sweater in his book-lined study at home near York — telling us what we now have to do: stay inside, stay safe. That the way to win against COVID-19 is to protect each other, and then we’ll be okay. We’ll beat this. He’s been measured and calm and confident. Suddenly — surprisingly — a different Tom Wolf has emerged, right before our eyes.

For most people, Wolf, who has run the state for five years now, has been … what, exactly? The bland governor with seemingly constant budget problems, who’s been trying to get his hands around the opioid crisis, who’s big on education. He seems nice. We know he’s smart, and his landslide reelection against arch-conservative rabble-rouser Scott Wagner two years ago wasn’t so much a mandate as a sigh of relief — Wolf’s not threatening. And that’s about all we know.

Which isn’t entirely his fault.

Ed Rendell, who has been, of course, both mayor of Philadelphia and governor of the state, cites the difference: “Mayors are first responders.” Something happens — a cop gets shot, City Council does something inane — there’s Philly’s mayor on the news at six and 11, talking us off the ledge of crisis or stupidity. As governor? You grind away at the awful morass of Harrisburg infighting. What’s there to watch in that?

Now, though, we need our governors; they’ve suddenly become our first responders. If Andrew Cuomo is a force — even something, for good or ill, of a bully — Tom Wolf is cut differently, never veering from his even-keeled style despite the news.

“This virus is spreading rapidly. It’s in every corner of our state,” he said on April 1st via video from his home. “Some of you might think that a month is too long to go without seeing your friends or family. But if we don’t do everything we can to slow the spread of COVID-19, there are some people who you will never see again.”

He’s been speaking to us since March about actions he’s taking: closing schools and non-essential businesses and calling for the entire state to “please stay home” and for all of us to wear masks in public. Which is not to say he’s necessarily gotten it all right. Wolf pissed off a good portion of the state’s businesses with his first, confusing “life-sustaining business” list, for example, that designated what could stay open; and Jim Kenney called him, yelling, when the Governor closed schools in Montgomery County without a heads-up to Philly, which abruptly ramped up pressure on the Mayor to act.

But Wolf has been there before us: deliberate, with a plan backed by science, reasonable and reassuring, firm and direct, and, perhaps most important of all, calm. It’s a sad day when those qualities come across as refreshing in a political leader. But here we are, and it seems we have gained, at any rate, a new way to get to know Tom Wolf.

When Wolf ran for governor six years ago, he had an appealing story as an outsider who took idiosyncratic career turns. He was a book-a-day-reading intellectual, something state government hadn’t seen at the top since Bill Scranton, with an award-winning doctoral dissertation at MIT on the U.S. Congress of the late 19th century. That led to job interest from Harvard, but he passed.

Instead of becoming a career academic, Wolf came home to Mount Wolf, a town of about 1,400 near York named after his great-great-grandfather, to manage a hardware store owned by his family’s kitchen-cabinet business. He and two cousins eventually took the business over.

And then politics came calling, in a big way. Wolf had been involved in local issues for three decades; after he gave generously to Ed Rendell’s reelection campaign for governor in 2006, Rendell made him state secretary of revenue. It was a springboard to run for governor himself in 2010, but then he took another left turn: The family business, which Wolf had sold, was failing. He aborted his gubernatorial run to buy back the Wolf Organization in order to save it. That seemed to be that.

But then — with a fresh opportunity against the hugely unpopular Tom Corbett — Wolf won in 2014.

He had a lot to learn. His team would craft a pristine über-progressive budget with a huge increase in education spending, which was, of course, roundly rejected by the Republican-controlled General Assembly. In 2016, when Wolf was almost two years in, his chief of staff, Mary Isenhour, told me that the Governor was on a steep learning curve in Harrisburg: “He was a little surprised that they weren’t just saying [about his free-spending budget], ‘That’s a really good idea, Governor, and you’re a really good guy, and I know you’re here for the right reasons, so we should do it that way.’”

Wolf’s naivete was shocking (as was Isenhour’s willingness to discuss it), and I wrote a piece four years ago that was tough on him. Wolf was his own man, all right, but clueless about political infighting.

Yet Wolf had slowly begun to show his mettle, publicly calling the Republicans’ version of a budget “garbage” in late 2015 and inviting legislators to find another job if they couldn’t do better.

I touch base with a couple old friends of Wolf’s whom he met at MIT 45 years ago. They both tell the same story — independent of each other — when I probe for a deeper understanding of the Governor’s preternatural-seeming steadiness.

Wolf was a teaching assistant for a course on American politics when the professor suddenly took his own life. What is still striking to Wolf’s friends was how he stepped in to teach the course: “What he wore on his sleeve was a composure,” Dick Samuels, now a political science professor at MIT, remembers. “A determination to make things right for the people who were affected.” Wolf was 28.

In an email to Drew Altman, a doctor in California, I suggest that Wolf seems to have a strength of conviction and an overriding calm that might serve a leader well in this moment.

“Exactly,” he writes back. “All he has to do is be himself.”

On Super Tuesday, March 3rd, Tom Wolf was a guest on KDKA radio in Pittsburgh to discuss the election. He first gave a shout-out to Grandma Peg Mueller — the grandmother of Wolf’s son-in-law — who’s a faithful station listener. Wolf then gave a brief nod to the risk of coronavirus; the Governor said Pennsylvania was ready, that a command center had been set up weeks earlier in Harrisburg, that the state was stockpiling medical supplies for “if and when we have a case here in Pennsylvania.” Then Wolf talked election politics.

My, how long ago Super Tuesday seems now.

But three days later, there were two confirmed cases in the state, and the crisis took off. Governor Wolf would spend the next month sharing increasingly bad news.

Through March, Pennsylvania Secretary of Health Rachel Levine gave a daily video report on the number of COVID-19 cases in the state: 11 on March 10th, 14 the next day, and a week later, 96. In short order, Wolf began closing the state’s schools, forced all but “life-sustaining” businesses to shutter, and, county by county, pressed people to shelter in place, to leave their homes only when absolutely necessary.

And every other day or so, he talked to us, both broadly and directly, about what was going on, usually after Levine’s update.

By March 23rd, the crisis was growing extreme: “I’m speaking very frankly to you about the situation this afternoon,” he said from Mount Wolf, wearing a gray sweater, tall bookshelves behind him. “Most of us have not experienced a disruption in daily life of this type ever before; our Commonwealth has not experienced a disruption of this magnitude in its supply chain since at least the Civil War. We will not come out of this unscathed. But if we work together, we can prevent more damage to our economy, more damage to our people and to our way of life.”

Then the Governor got more personal: “Frances and I had our second grandchild, and we both desperately want to hold him. But for his safety, and for the safety of the rest of our family, we are distancing ourselves, and I’m asking all of us to do the same thing. … The point is, before we can recover, we must survive.”

What we needed to do, Wolf explained, was buy time, to let our health-care system catch up, so that we didn’t become another Italy. He knew how that sounded, but that’s all he had.

Andrew Cuomo is a lightning rod for our frustration and fear as he baits and works the President. Not Wolf. He’s given virtually the same measured performance with each presentation to the public, even as the news continued to get worse, and Rachel Levine has sounded almost cheerful as she announced the rising numbers. “It’s a collaborative process in crafting the message that we want to convey to the public,” Levine says when I reach out to her, and it comes straight off the Governor’s M.O.: “Which is to stay calm.”

But while Wolf can come off as downright boring when he’s talking budget matters or schools, he has imparted a sense of staying a course, and how he needs our buy-in on how we take care of each other. That getting through this is up to us.

Wolf’s brand of leadership hasn’t played well in some quarters.

A state manufacturing-association official, for example, livid at what he sees as the willy-nilly list of “life-sustaining businesses” the Wolf administration came up with that meant the closing of many necessary services on March 19th, argues that the Governor made a mistake in self-isolating for two weeks at his home in Mount Wolf: “Which left a bunch of woke 20-something micromanaging busybodies who never signed a paycheck making decisions in Harrisburg.”

The “life-sustaining business” list did confuse a lot of people: “We thought we’d have to empty out hotels,” says Ed Grose, the Philadelphia hotel association executive, which proved incorrect. Meanwhile, prison reform advocates, worried about the spread of the virus among close-quartered inmates, criticized Wolf for not acting sooner when it came to at-risk prisoneers. (Wolf finally announced on April 10th that he would grant temporary reprieves to as many as 1,800 non-violent prisoners.)

And there was Mayor Kenney’s rage at not getting even a phone call from Wolf before the Governor closed the schools in neighboring Montgomery County. Tom Farley, Kenney’s health commissioner, has floated the idea that Andrew Cuomo is in Wolf’s decision-making inner circle.

The criticism and anger and lashing-out is understandable with so much unknown and so much at stake. I run that last one — the accusation that Cuomo has been giving our Governor his marching orders — by Rachel Levine. She laughs at the very notion: “I can guarantee you the Governor is not following the marching orders of anyone.” Then I get a call after talking to Levine: One of Wolf’s assistants wants to email me a timeline on coronavirus decisions the Governor has made, to disprove the Cuomo accusation. This doesn’t come across as oversensitivity so much as a recognition of the moment: A great deal is at stake for Tom Wolf, too.

Regardless of the surrounding noise, Wolf will keep trying to lead us in his particular way. On March 30th, there was no Rachel Levine giving a daily update; Tom Wolf was in her place, announcing, “Let me first say, Dr. Levine is taking a well-deserved day off today.” The Governor had sent her home for a nap. “I drove up [to Harrisburg] today for the first time in two weeks, left my house in York County, drove my Jeep, and was really impressed with what I saw. We Pennsylvanians are really doing a phenomenal job — parking lots were empty, roads had very few cars. … Thank you to Pennsylvanians, thank you for staying in, thank you for doing what it’s going to take to defeat this virus.”

Wolf was, for a moment, a man who had had to hole up just like anyone and was finally out and about, just like the rest of us hope to be. It was a moment devoid of anything except a simple connection that sent us a message of what we must continue to do.

Listen. Please.

Published as “First Responder” in the May 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.