5 Ways Philly Was Doing Well Before the Pandemic

Pew's just-released report paints a picture of a city on the rise in 2019, with unemployment at an all-time low. By understanding where we stood before the pandemic, we might learn what to expect on the other side.

The Schuylkill River Park Boardwalk in springtime

We’ve written about quite a few Pew reports here at Philly Mag — but none compare to 2020’s, which was released on Wednesday. The report reflects Philadelphia’s upward trajectory, including gains in population unseen “since the 1940s,” but it’s also entirely ominous in addressing the elephant that walked into the room a few weeks ago: the COVID-19 pandemic.

“At the beginning of 2020, economically, the indicators were pretty positive” in Philly, says Larry Eichel, senior advisor for Pew’s Philadelphia Research and Policy Initiative. “But a lot of this is now subject to change.”

Local officials are handling the public health crisis by encouraging social distancing and providing testing and daily updates, among other measures. But like virtually all other cities, Philadelphia is bound to take a hit because of the pandemic.

Right now, we don’t know how widespread or drastic its effects will be — or where we’re most susceptible to losses. But before we speculate, looking back at how Philadelphia was faring before this massive storm could help us in the future.

“It’s important to be aware of where we were before the pandemic arrived, because it helps focus attention on the issues that await Philadelphia once the current situation changes,” Eichel says. “Those issues involve poverty, jobs and crime, among others, and at this point all we can do is raise questions.”

Here are five ways Philadelphia was doing well before the pandemic, and what to look out for moving forward.

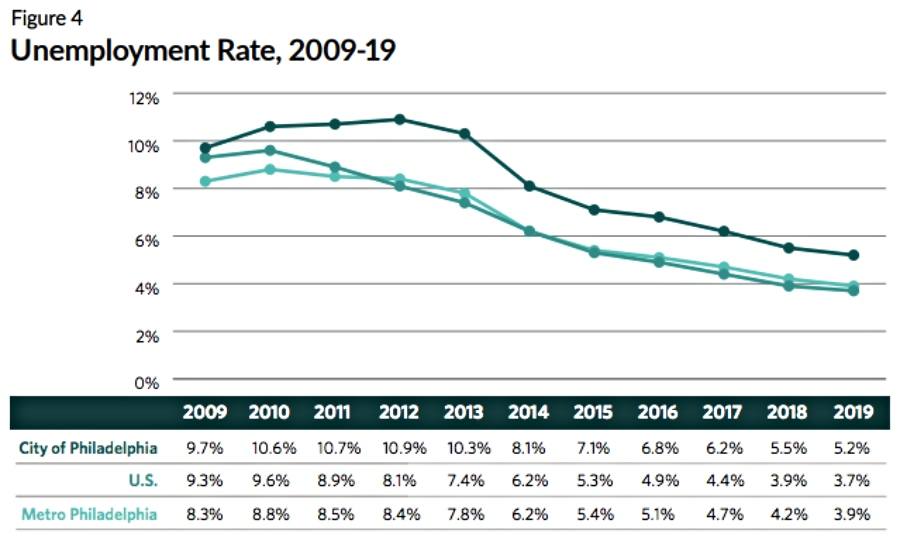

1. Unemployment was at a historic low

Continuing on a seven-year decline, Philadelphia’s unemployment rate averaged 5.2 percent in 2019. That’s higher than the national and regional rates — but it’s the city’s lowest in decades, which the Pew report called an indicator of Philadelphia’s expanding economy.

Graph courtesy of the Pew Charitable Trusts

But this is one area where we’re certain to feel the effects of the pandemic, and indeed we already have. As of Saturday, one in six Pennsylvania workers had filed for unemployment sometime within the last three weeks, representing nearly 1.1 million residents.

Eichel says he and other researchers will be watching for whether the spike in unemployment represents “a short term setback or a longterm problem.”

Other issues represented a threat to the city’s prosperity even before the pandemic, including Philadelphia’s stubbornly high poverty rate. Just under 380,000 Philadelphians (or roughly 25 percent of the city’s population) were living in poverty in 2018. Another 86,000 people were living just above the poverty line. Families in those households who depended on full-time or part-time jobs are “subject now to falling deeper into poverty,” Eichel says. “That’s really a concern.”

2. Job growth was at its highest since 1990

Job count stood at 741,200 in 2019 — even with the closures of Hahnemann University Hospital and the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery, two of the city’s largest and most established private employers.

Graph courtesy of the Pew Charitable Trusts

Crucial economic drivers — like the medical, hospitality and education sectors — contributed to that rise, per the Pew report. The increase in job growth across the board in Philadelphia outpaced the national rate.

As with the likely rise in unemployment, we’re all but guaranteed to see a notable decline in job growth during and after the pandemic. Restaurants and small businesses are struggling. Major employers could take a serious hit, too: Comcast had yet to announce any layoffs as of late last month, but one wonders how the postponement of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games will affect the company, whose NBCUniversal owns broadcast rights for the event.

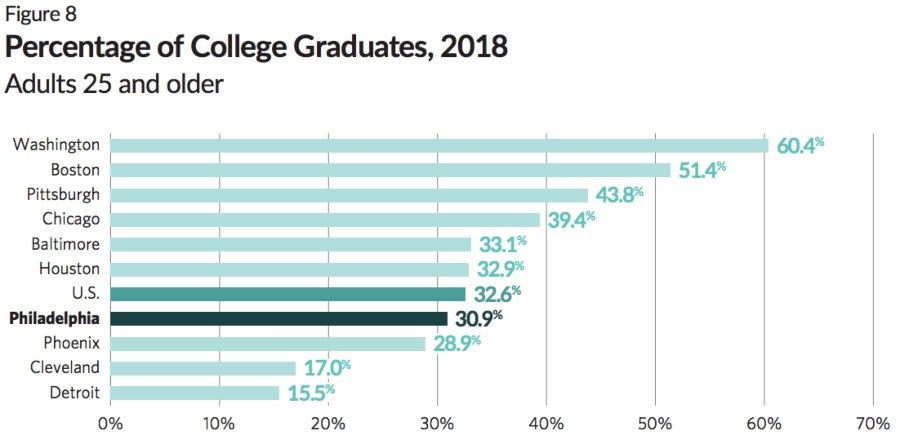

3. The share of Philadelphians with a college degree had grown

The share had reached 30.9 percent overall in 2018 — up from 21 percent a decade earlier. This marks the first time the share exceeded 30 percent, per the Pew report. For adults ages 25-34, the share was higher — 45.1 percent — “making the city more attractive to would-be employers,” the report read.

Philadelphia still trailed behind comparison cities and the national average in this regard — but we were on the upswing.

Graph courtesy of the Pew Charitable Trusts

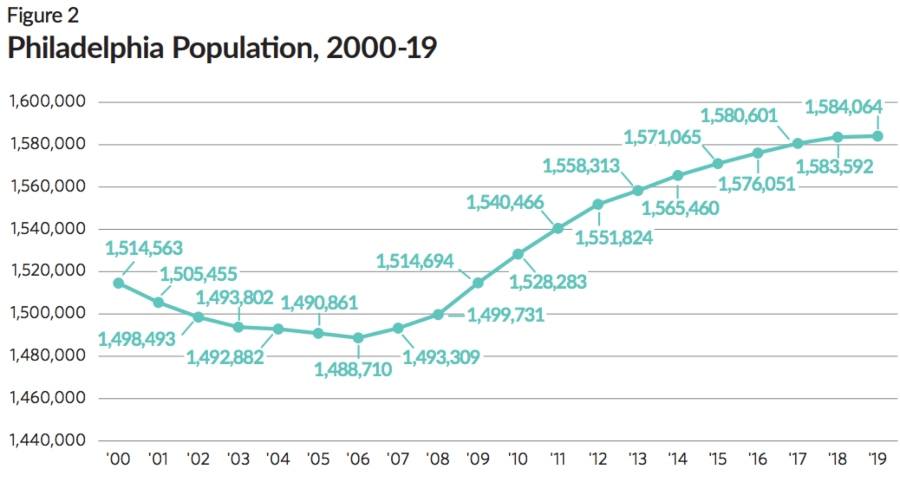

4. The population rose for the 13th consecutive year

However, the increase was pretty marginal in 2019: fewer than 500 residents. Still, since our population was at its lowest 2006, Philadelphia has gained more than 95,000 residents, thanks to factors like immigration and a boom in young adults. Combined with the city’s economic successes, the future looked promising in 2019.

Graph courtesy of the Pew Charitable Trusts

COVID-19 will surely affect our outlook, but it’s worth noting that other threats persisted even before the pandemic: our declining but still far-too-steep poverty rate, as mentioned, and an upsurge in violent crime, which rose 7.2 percent in 2019. Philadelphia’s homicide level was at its highest since 2007, which officials attributed in part to an increase in opioid misuse, according to the Pew report.

“The trends [in violent crime] were not positive,” Eichel says, and “had the potential to alter the city’s [overall] positive trajectory.”

Crime, including some violent crimes, dropped in the first week of quarantine in Philly. But it’s way too soon to say if that trend will continue. Among Eichel’s questions for the future: “Will the rise in homicides continue, or will Philly become a less violent place?”

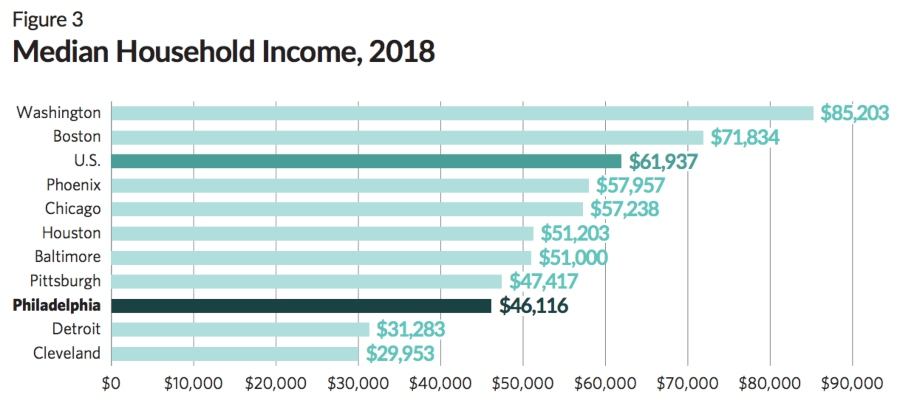

5. The city’s median household income was up

Here’s another area where we’re still far beyond most comparison cities (except Cleveland and Detroit) — but getting better. Philadelphia’s median household income rose to $46,116 in 2019, a “healthy margin,” according to the report. Since 2016, median household income rose by 11 percent.

Low-income and minority communities could be hit particularly hard by COVID-19, though, putting those renters and homeowners at risk. For now, the city has vowed to suspend evictions until April 30th— but the pandemic’s affects will last long after that.

Graph courtesy of the Pew Charitable Trusts