Penn Med School Dean Says Philly’s Coronavirus Crisis Won’t Peak Until May

According to top medical experts, Philly’s COVID-19 problems are only beginning.

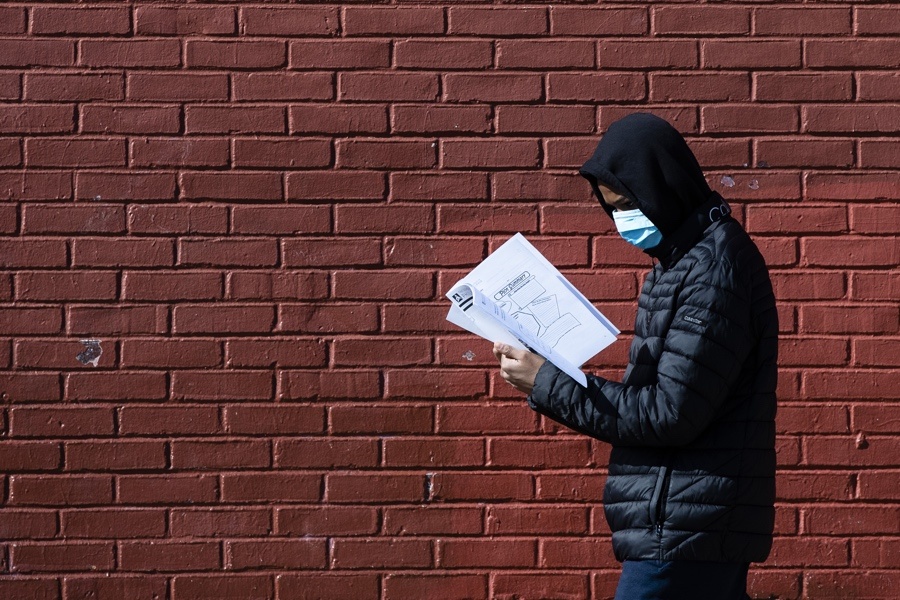

A Philadelphian wearing a protective face mask on Thursday, March 26. Residents are ordered to stay home, with few exceptions. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

The coronavirus outbreak continues to escalate across the U.S. and in Philly — and according to Dr. J. Larry Jameson, Dean of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, we’re nowhere near the worst of it yet.

As of Thursday, the Department of Public Health listed positive cases in Philadelphia at 637, but the numbers are expected to increase rapidly due to continued community transmission. (Alarmingly, a large number of the Philadelphians who have tested positive for COVID-19 come from a cohort made up of millennials and Gen Z.)

Despite the increasing COVID-19 positive cases and rising death count, President Trump said recently he wanted to have U.S. coronavirus-related restrictions lifted by Easter, or April 12th — a move which seems dangerous and irresponsible to top health experts, including Jameson. In response, in a March 24th opinion piece in The New York Times, Jameson called for all politicians to “save lives, not Wall Street” by keeping businesses and schools closed, as well as maintaining tough social restrictions, for the foreseeable future.

He wrote, “these steps will actually ensure our economic health, since commerce cannot thrive until we have substantially contained the virus.” The plea to government officials was backed by the leaders of Penn Med as well as six other prominent U.S. academic health systems from NYU to Johns Hopkins Medicine to University of California, San Francisco.

In a phone conversation, Jameson told Philadelphia magazine what we can expect in the next few months.

PM: When do you expect the coronavirus peak to happen in Philly?

Jameson: We’ve been modeling this at Penn Medicine using an application that is publicly available. It’s called Penn-Chime. It predicts we hit our peak in the middle of May. Exactly which day will depend on how much physical distancing we can accomplish to reduce the viral spread. If you look at the pattern, we’re just at the beginning of what could be a very rapid increase here in Philadelphia. As I model it today it looks like May 18th, but it depends on the rate of spread and how much impact people will have by changing their behavior. I would call it middle of May.

At that peak, how many patients do we expect to see on ventilators?

The data is a little softer because there are so many assumptions built in. We’re basing the model on the patients we’re taking care of at Penn. But using our own information, it’s going to be in the thousands.

How long does it take to for a person’s body to go through the infection?

When people are exposed to the virus, it takes on average five to seven days before those who have the virus and will have symptoms actually have any symptoms, and that’s just because the virus is beginning to spread in the body and the body is beginning to react to it. But then the body will develop a variety of symptoms, most commonly shortness of breath, a dry cough, fever. In some ways, fever is the best predictor, based on the data from China, of when your body has finally mounted a good response to this. When the fever breaks, people start to get into a recovery phase. That total course can be a 20-to-25-day period.

What about people who don’t have symptoms?

At least 80 percent of people have mild enough symptoms that they can stay at home. Some people don’t have symptoms and don’t even realize that they’ve got this, but they could still be spreading it. That’s why it’s extremely important, and something you can convey to the Philadelphia community, that people that are completely asymptomatic can be spreading the virus. My advice is that universally people should assume that they could be carrying the virus, or anyone that they encounter might have it. That’s why the recommendations of physical distancing of at least six feet and the hand-washing recommendations, how to cough into your elbow, are really important. It’s the most powerful tool we have to slow the rate of spread.

What does Philadelphia as a city need to do in these next few weeks to combat this?

It’s important for everyone in Philadelphia to realize they have a personal role to help address this pandemic. We have very brave people who are first responders working in the hospital; we have 45,000 people employed at Penn Medicine; 9,000 are doctors. You’ve got a lot of nurses, people working at the front desk — all of us can help protect those healthcare workers by not having this incredible large surge which is going to be challenging for them to manage. We can keep them safe. I like to think of our healthcare workers in the same way that we support our military. We need to look out for them. They’re working hard to protect all of us.

What does social distancing actually do?

It reduces Philly’s peak. We don’t want our peak to be a high one, because it will overwhelm our healthcare system. If the virus were to double every two or three days, it would be like a tsunami hitting the healthcare system. If we can slow it down, that wave is much lower, and the peak is much lower. It’s also buying us time to develop more effective testing, to screen for drugs that can be treatments, and to develop vaccines. At Penn, we have a whole center dedicated to coronavirus research, and there are active projects to develop tests, some of which can be performed in the home so we can get more rapid population-based information. There’s research to develop novel vaccines in collaboration with a company here in Philadelphia called Inovio. So the reason to social distance is to buy time to develop these treatments that are ultimately going to be the way that we conquer this.

Why did you and other health leaders feel you needed to call for businesses and schools to remain closed in your recent Times piece?

I’m a doctor. I’m focused on the health of individual people and the population. I think the priority has to be on saving lives. I think if we were to relax the measures being rolled out too early, we’re going to accelerate the spread of this and it’s going to be devastating. It’s very predictable. We’ve seen the models in other countries; we’ve seen how this plays out; we’ve seen what’s happening in the New York area. It will begin to spring up in many different parts of the country and spread, just like it has in every other place on the globe where it’s occurred. In the near term, we need a sharper focus on tests, identifying people who were infected, putting people in isolation or quarantine, and try to bring this under control more quickly.