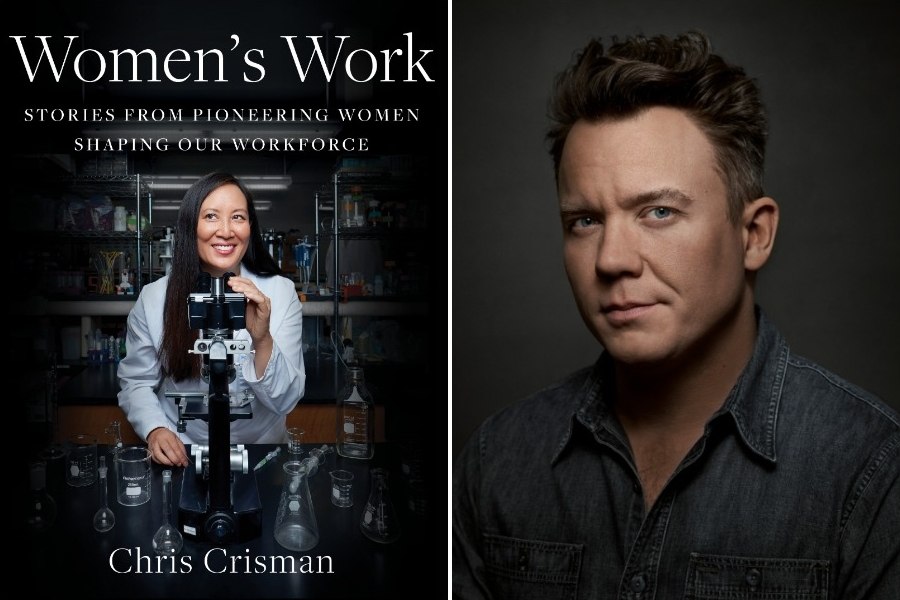

This Local Photographer’s New Book Features 56 Stunning Photos of Women at Work

Chris Crisman’s Women’s Work includes interviews with Heather Thomason of Primal Supply and Penn’s Angela Duckworth, among others.

Chris Crisman’s new book, Women’s Work, features 56 stunning photos of women at work.

Chris Crisman was raised in rural Pennsylvania by parents he describes as “undeniably DIY.” They heated their home — about 100 miles north of Pittsburgh — with wood they cut themselves. They grew their own food, relied on rotary antenna for their TV signal, and had a washtub but no shower.

Crisman, a local photographer (his work has appeared in Philadelphia magazine), wrote about his childhood in the beginning of his book Women’s Work, published this week by Simon & Schuster. He grew up watching his parents and learned that “no jobs were off-limits in our home.” Chris saw less of his father because of his long shifts at the nearby steel mill. But he helped his mother, Karen, run her own dog-grooming operation, witnessing “firsthand not only her dedication and work ethic, but also how she balanced the challenges of being a mother and wife with being a business owner.”

Women’s Work features stunning photos of women like Karen Crisman in their job settings. Its subjects are women all over the country, including in and around Philly; you’ll find Primal Supply owner and butcher Heather Marold Thomason, Penn’s Angela Duckworth, C-suite executive searcher Judith von Seldeneck, Army NCO/CBRN Tiquicia Spence, Bucks County architect and furniture maker Mira Nakashima, and more. There’s a heroic quality to the photos that makes them extra-arresting, and they’re accompanied by the women’s stories in their own words.

We caught up with Crisman to talk about his experiences in conceiving and creating the book.

As you write in your intro, your mother was a huge influence on you. Is this project something you’ve always thought about? And how does the current moment shape this book?

It wasn’t a lifelong goal to make this book, but it’s in the lane of familiarity. When I was growing up, my father worked from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m., so if I wanted to spend time with him, I had to work. The biggest influence for me in business is my mother. She was an entrepreneur running her own business by herself, doing sales, execution, customer service, behind-the-scenes work. Today, and including with my wife, I’m often very drawn to people who work, whether it’s manual labor, craft labor or skilled labor. And as a photographer, I have a general curiosity about juxtapositions that registers visually. A few years ago, I met with a producer in New York City, and she told me about her friend who had quit designer work and wanted to be a butcher and move to Philly. I reached out to her. Up to this point, the image in my brain of a butcher was a bulbous white man, probably bald, with a bloody white apron, standing in front of a shop with his arms crossed. That’s what the archetype was. But Heather Marold Thomason is a different person. That was intriguing to me. And that spawned another shoot, and I started to feel like, “Okay, this is a project.” I’m just massively impressed with [the women in the book], and they’re retelling their stories in a cool way.

Heather Marold Thomason | Chris Crisman Photography LLC

What other juxtapositions come to mind?

We wanted to find more women who are in careers that historically are male-dominated. I think we — and I say “we” because I have a team in-house — had ideas that were pretty blue-collar, and I think that’s me thinking blue-collar jobs photograph pretty well and offices don’t photograph quite as well. I thought, “Hey, this is interesting because it feels different to me, and it looks different to me, to put a big body of work together showing the opposite of what you expect but what is actually the wonderful reality.” This is normal. This is essentially saying: Limits to careers should not be based on sex, gender, any sort of demographic, any sort of race, any sort of anything.

Some of this work was released as a photo series a few years ago?

That was the start of the project. It was, again, about a curiosity about jobs that I’ve never done. I’ve done magazine editorial work for a long time, shooting all over the country. And a lot of it was about, “Oh, I want to photograph X. Anyone doing X?” For example, I really love shrimp, and I wanted to see what it’s like to be on a shrimp boat. We ended up in a lobster boat. We ended up in a gold-mining operation for some of the original shoots. There were a lot of cool blue-collar jobs at the get-go. Then, in fall 2016, we released an early version of the project and got a lot of feedback about reaching more people [in other careers].

Sophi Davis | Chris Crisman Photography LLC

What was the feedback like?

There were some experiences that really motivated me to go forward with the book. A fifth-grade teacher in France reached out to me. She was trying to have a healthy debate about, “Is there any job that a woman can’t do?” She was hoping to get some of the pictures. We sent her everything. The idea of reaching children is cool and one reason I kept my mouth out of [the book] — my writing, there’s only three or four pages. I wanted to stay out of it as much as possible. My voice, in the way that I make work, is there, and clear. But I wanted these women to tell their stories.

Did you have a say in the cover? You started out with a lot of blue-collar jobs, but it features a woman in STEM.

As time went on, I began seeing the lack of women in just about every industry, STEM in particular. I think that’s really important. Did you read Yoky Matsuoka’s story? She’s a VP at Google and a pretty amazing person. Hers is one of my favorite photo sessions. As far as the cover, it’s a group decision. I love [chemical engineer] Connie Chang’s picture. And you know, the book kind of feels like a science textbook to me. For a while, I took that as a negative. And now it feels like a science textbook in a way that I’m starting to love.

Damyanti Gupta | Chris Crisman Photography LLC

It does feel like something you can study to learn about working women at a particular moment in time. How did you pick these 57 women?

I think there were 15 women in the original project, maybe 16. That was its own body of work. Then it took about a year and a half for me to fully commit to doing a book. We had a timeline that was like, effectively, most of two years. I felt like doing normal business plus adding this project was going to be pretty brutal. We did offset it, because I had shot some really amazing women already. So we brought legacy work into it, like the portraits of [basketball coach] Pat Summitt and the picture of my mother. I wanted to focus on people who had made an impression on me. And I reached out to a lot of other women. A quarter or maybe a third [of the book] is legacy work. Everything else is new. And diversity was important to me.

Do you have any favorite photos?

I felt really, really lucky to get Angela Duckworth. And I thought there was a really unique story about Mira Nakashima. Mira, [the woodworker George Nakashima’s daughter, who lives and works in Bucks County] is an incredible woodworker in her own right. Typically, if your family does a thing, it’s going to influence your thing. But her work is totally special and unique. Her dad is certainly an influence, but not the only one. I think if she were George Nakashima II, she would get different treatment. Father/son lineages and businesses are romanticized. The father/daughter element is there, of course, but I don’t believe her work gets enough credit. And the book talks about that. She opens up about her father. And one of the most fun shoots was the Heidi and Renae Moneymaker shoot and Mara Reinstein, the film critic.

Heidi and Renae Moneymaker | Chris Crisman Photography LLC

I want to talk about the scope of the book. In what way does showcasing women working reveal a picture of women in general, and in what ways does it limit what you’re saying about women?

Well, number one, this is a very small sample size. It’s 57 individuals across an entire species. And to be frank, it’s a very American book. We can’t speak to everyone. But I hope people find a commonality — jobs — and I think the book should transcend politics and hopefully allow people to see a little bit of the other side of the mountain. A point that came up before is … it’s a man doing the book. But men should be able to stand up for women. I think it’s positive. You see pictures of a career, and then you read the stories from the women themselves.

Yoky Matsuoka | Chris Crisman Photography LLC