Special Elections Are Undemocratic, Wasteful and Downright Stupid

After voting in a special election for a second year in a row, I’m convinced: This is Philly politics at its worst.

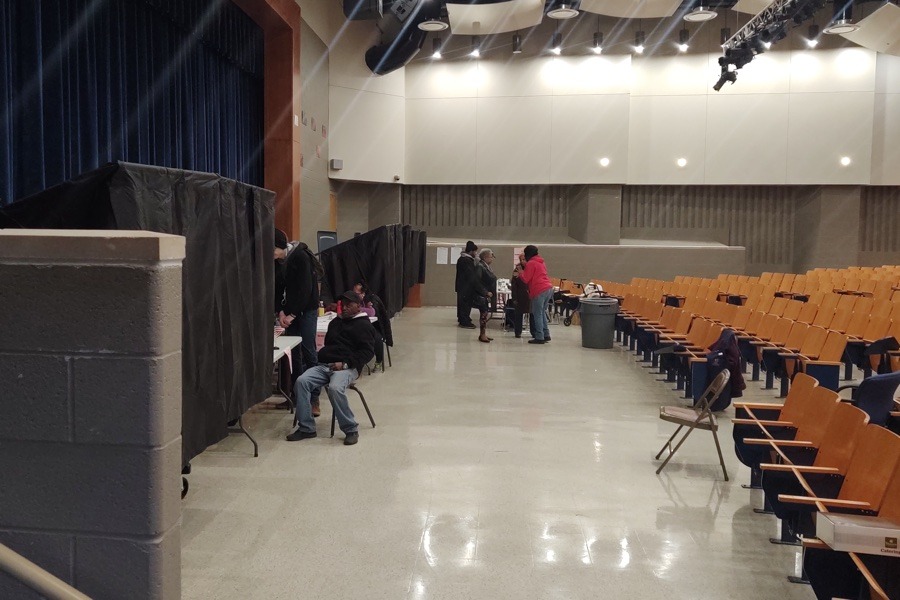

Th special election voting location at West Philly High School was nearly empty on Tuesday.

Tuesday nearly broke all that was left of my faith in the democratic process.

I’m what many would consider a super voter, given that I’ve cast a ballot in every possible election (local, state, and national) that I’ve been legally eligible to participate in since turning 18 a decade ago. I don’t take for granted the freedom of making my voice heard at the polls; it’s something my elders fought hard for during the Civil Rights era.

But after recently casting my vote in a special election in West Philly, I found myself hating the process and feeling cheated.

It wasn’t problems with my voting machine or voter suppression tactics infringing upon my rights; it was simply the election itself. Special elections, which are used to choose a replacement in the event of a sudden vacancy of a district’s seat, are the dumbest, most pointless political event in Philadelphia.

I know it might be considered crass to suggest that any opportunity to vote is pointless — but there’s just no other way to describe the current nature of special elections in this town.

On Tuesday, for the second year in a row, I had to show up to the polls to cast a vote in a special election in the 190th legislative district. After voting for Movita Johnson-Harrell during last spring’s special election — she won the seat following the resignation of former state representative Vanessa Lowery Brown, who was convicted of bribery and other charges — I now had to vote again since Johnson-Harrell resigned after being charged with stealing more than $500,000 from a nonprofit she founded. (She’s disputed the allegations.)

At 4:38 p.m., I was only the 23rd voter at my polling area at West Philadelphia High School. The room had more volunteers and committee people than voters. Even receiving the once-sacred “I voted” sticker felt silly since there were only two candidates on the ballot for state representative: Democratic nominee Roni Green and Republican nominee Wanda Logan.

Honestly, we all knew how this was going to play out.

With 87 percent of my district registered as Democrats, Green predictably won the seat by a landslide with 85.5 percent of the nearly 3,000 votes cast. Considering the fact that Green, a business agent for SEIU Local 668, raised $61,736 in campaign contributions (mostly coming from SEIU), one can’t help but be infuriated by the excessive spending.

But that’s just one reason special elections can be perceived as being undemocratic. Even more disturbing is the fact that all of the potential hopefuls vying for the party’s nomination don’t get to be considered by voters. Unlike in primaries, where multiple candidates from a single party can openly compete for a seat, in special elections there’s just one candidate per party — a candidate chosen by the party’s bosses. And what makes that particular nominee so damn special to begin with? Is it based on whether they can raise the money to keep committee members and ward leaders motivated to work the polls? Are there other factors that the public can’t see that go on behind closed doors? It should be noted that Johnson-Harrell was the Democratic Party’s third choice in the special election last year, after two other top picks failed to meet the necessary qualifications to get on the ballot.

In other words, special elections are deliberately designed to give the political party currently in possession of a seat an unfair advantage in selecting who’s going to be the next successor.

Unlike any other election, this one pretty much makes voting an afterthought because the outcome is so blatantly obvious that it insults voter’s time. The low voter turnout in the 190th district’s special election wasn’t because people don’t care. It was because the party didn’t want them to. There was little promotion of Tuesday’s election, and the last-minute press conference held in West Philly over the weekend by the city commissioner was a mockery of the democratic process altogether.

Want to make special elections more meaningful and engaging? Either the political parties should make their nomination processes more public, accessible, and transparent to voters — or the race should be open to all qualifying candidates. Otherwise, if this rigged system continues, I might just break my perfect track-record of voting in all elections.