If You’re a Good Citizen, Delete the Citizen Policing App

Some 200,000 Philadelphians are said to be using it. But crowdsourcing live footage of crime scenes doesn’t make you a superhero — it makes you a voyeur.

The Citizen app encourages users to live-stream footage from crime scenes. Photo by Caroline Cunningham.

Almost every story about the crime-reporting app Citizen starts the same way. The writer tells, in great detail, about a series of crimes that were just committed. The writer knows this not from pounding pavement, or from riding shotgun next to a police officer; in fact, to paint this portrait of crime in the city, we soon learn, the writer didn’t even have to leave the house!

The secret behind the sleight of hand is the app, which sends notifications, and sometimes live crowdsourced video footage, to nearby users whenever a 911 call reports an alleged crime affecting public safety. The philosophy of the app, which launched in Philly in April of last year and now has (according to the company) more than 225,000 local users, boils down to this: The best shield against crime is information. Armed with that, people know when to stay away. But Citizen sends a second, conflicting message: If you don’t want to stay away, would you mind shooting some video of the live crime scene?

In more ways than one, Citizen suffers from a split-brained identity crisis. When the app was first introduced in New York City in 2016, it wasn’t called Citizen; it was dubbed Vigilante. A launch video, since de-listed from the company’s YouTube page, feels like the opening sequence for an episode of Law and Order: SVU: A man in a hoodie stalks a woman walking under a bridge as yellow-tinted fog circles the street. She calls the police. Cut to the Vigilante headquarters, where an employee monitoring the 911 feed blasts out a warning: “Suspicious Man Following Woman.” Two men see the notification, drop what they’re doing, and jump into action. By now, the guy has the woman pinned up against her car. And just when the graphic scene reaches its unnerving peak, the two men pull up, before police arrive, phone cameras broadcasting. The criminal runs away. Vigilante justice has been served.

The authorities were unimpressed. The New York police department said in a statement, “Crimes in progress should be handled by the NYPD and not a vigilante with a cell phone.” Apple took the unusual step of banning Vigilante from its app store altogether. Eventually, Vigilante rebranded as Citizen. The app’s founder, Andrew Frame, said in a later interview that the name Vigilante had been a “poor choice.” (Tellingly, he also said, “Everyone thinks we changed the app, but we really didn’t.”)

Though Citizen signaled it would cast off its superhero cape — and in doing so earned the support of those previously skeptical police departments — it has demonstrated plenty of vestigial vigilante behavior. Two years ago, when Citizen launched in San Francisco, it did so with an ad not unlike the one that had aired in New York. Another video, uploaded by Citizen to its official Vimeo page in the summer of 2018, is titled “Catching a bad guy on the Citizen app.” Current Citizen ads are considerably more low-key, hewing to a message of We democratized 911 rather than one of heroes whose superpowers are a lack of common sense and an iPhone.

And yet: Citizen still encourages users to shoot video footage of crime scenes if they’re nearby. (Dominic McMullan, a Citizen spokesperson, wrote in an email, “We discourage users from walking into dangerous situations. … We are not aware of any instances of people putting themselves in danger by using the app.”)

Everything about Citizen seems to exist in similarly opposed binaries. Before using the app, you must decide: Is it better to be fully informed of all crime and possibly paranoid, or blissfully ignorant but constantly in danger? Meanwhile, though the app’s mission statement is to “keep people safe and informed,” the truth is, the feature that sets it apart from citywide crime databases or other notification systems is the video live-streaming, and far from encouraging people to stay away from a crime, video requires that people approach the scene. According McMullan, the app sends “hyper-localized notifications.” But it’s also the case that every Citizen user can search crimes committed in other neighborhoods — even other cities — that have no relevance to them whatsoever.

So while Citizen professes to be a benevolent actor that informs people about and protects them from nearby crime, the app’s own functionality — wide-ranging search and a live-streaming function — sends a different message entirely.

Last Tuesday, my phone buzzed with a Citizen notification: THREE INJURED IN SHOOTING. I was in West Philly, nowhere near the 400 block of Fitzgerald Street that the notification concerned, but I pulled up a video, which was eventually viewed more than 40,000 times. “We heard about 10 rapid-fire gunshots earlier … Definitely not fireworks,” a man with the apt user name GunsOrFireworks narrated. In the dark, wobbly video, we see cops bending over to pick up shell casings as a crowd of onlookers watches. In the app, a stream of hearts pops up, then evaporates on screen — other Citizen users sending emoji well-wishes from afar.

As is the case with many Citizen live-streams, the video offers no information that wasn’t already expressed in the earlier text notification. Even McMullan, the Citizen spokesperson, admits this: “The videos tend to be post-fact, mostly police cars and fire engines.” In other words: They’re not meant to supplant, or really even enhance, the primary text notification.

But by allowing and encouraging the masses to live-stream videos, Citizen opens up a Pandora’s box of potential abuses. This is particularly acute for people of color who face racial profiling. “If I’m walking down the street with a red hoodie on and someone gets an alert that someone with a red hoodie did something, then obviously I become an automatic suspect,” says Reuben Jones, a local community activist and criminal justice reform advocate.

While Citizen proudly states on its website that it has the support of a broad coalition of police, businesspeople, and community leaders, Jones claims there’s near-universal disdain for the app in Philadelphia activist circles: “There’s a lot of opposition to it.”

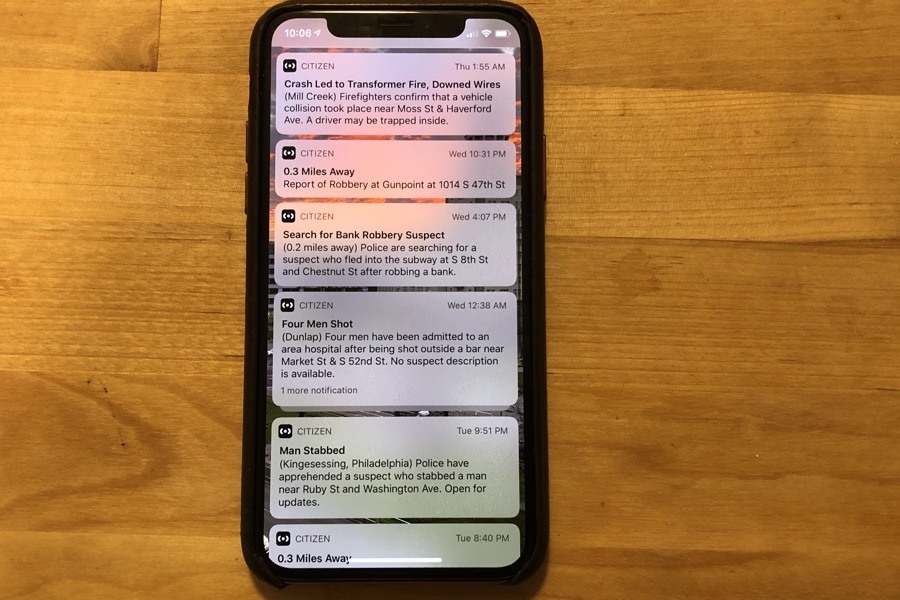

Three days’ worth of Citizen notifications. Photo by David Murrell.

I raise some of these issues with McMullan, suggesting that by allowing users to live-stream and access crimes citywide, the app might exacerbate a sort of voyeurism and stereotyping in neighborhoods with higher crime — which, as Jones puts it, will “stigmatize a whole community and put a whole bunch of people under additional scrutiny.”

In an email, McMullan rejects those critiques: “Citizen is the first app to combine location information with 911 intelligence to keep you and your loved ones safe. Unlike social media sites, the app is not designed to encourage time spent or engagement with content. Our success is measured by lives saved. To suggest Citizen is used for anything else fundamentally misunderstands the technology, mischaracterizes the user experience and misleads the public.”

But the reality is, Citizen does give users the ability to search and watch crime-scene videos from outside their area. And, like a social media site, Citizen also has a comment section, which — aside from providing a forum for inane remarks, as all comment sections do — worsens the more serious problem of potential false identifications. Posting suspect or victim descriptions violates the terms of service, but it can be difficult to moderate every crime thread in real time. Once, after an alleged bank robbery, I saw a user post a detailed description of a suspect with no sourcing whatsoever.

While there could be some appropriate use for searching citywide crimes — maybe you’re considering a move to a new neighborhood — there’s already a resource that provides a similar service: the City of Philadelphia’s official crime database. This is searchable by neighborhood, too — a fact McMullan notes while suggesting Citizen does nothing the city isn’t doing already. But there’s a difference: Citizen, with its sleek user interface, its comment section, and its crime-scene videos, makes popping in on those scenes across the city much more stimulating and interactive than browsing the city’s bare-bones website. (Citizen, for its part, says it doesn’t track whether or not users jump to other neighborhoods to view crime.)

Another concern: The constant crime notifications coming in through Citizen have the potential to shape users’ psychology, says Temple criminal justice professor Ajima Olaghere. Maybe someone watches a series of crime-scene videos in a neighborhood with boarded-up homes. There’s nothing criminal about boarded-up homes, but now an association has been made. In facilitating this, the app “reinforces perceptions of people’s ideas of crime and fear.” These “notions of ‘disorder,'” she adds, “stoke fear in people and often translate to a 911 call” even when nothing criminal is going on.

Citizen can also shift the perspective of longtime residents. Lynn Rinaldi, who has lived in Girard Estates for 20 years, never used to worry about coming home late at night after work at Paradiso, the East Passyunk restaurant she used to own. But she recently downloaded Citizen, and seeing all the crime notifications “created a little bit of anxiety for me,” she says. “I started to say, I’m not going to take my car out after dark; I’ll just Uber if have to go somewhere.” Though she decided to stop checking the app, it’s easy to imagine how Citizen could produce a self-perpetuating cycle in someone else: A user downloads Citizen and becomes more anxious about crime; the person becomes hyper-vigilant and starts calling 911 when something “suspicious” goes on; that, in turn, generates new Citizen notifications, which ultimately makes everyone else using the app more paranoid, too.

One of the challenges with Citizen’s real-time philosophy is that its alerts are derived from 911 calls, which are sometimes inaccurate. Though the app, now in nine markets across the country, has a team of 60 people monitoring 911 calls around the clock, vetting allegations in real time poses problems. In Philly, for instance, Hans Menos, executive director of the citizen-led Police Advisory Commission, tells me about a recent trend: When convenience-store owners have a nuisance customer, some have taken to calling the police and saying that the person has a weapon. “They wanted a more rapid response,” Menos says, “and they know if they just say they have a homeless guy in the store, police will make them a lower priority.” Suddenly, what would be a minor 911 call rises to the level of a (false) Citizen notification.

The issue of false notifications has led some observers to caution against taking Citizen too seriously. In one South Philly anti-crime Facebook group, members would regularly post screenshots of Citizen notifications to warn the broader community. Eventually, a community liaison with the police district wrote to the group, “PLEASE be aware of certain crime alert apps such as Citizen … Sometimes they DO NOT UPDATE their alerts properly, causing people to be up in arms.” Case in point: On Sunday night, Citizen notified people in Girard Estates about a “report of armed suspect” at 17th Street. In fact, it was apparently at 7th Street; 12 hours later, the warning still hadn’t been updated by Citizen moderators.

Beyond these concerns, it remains unclear how, exactly, Citizen plans to monetize. To date, the app has raised $40 million in venture capital funds. (Peter Thiel was an early investor.) But considering that the company says it will never serve ads on its platform or sell users’ locations (which you’re required to provide to use the app in the first place), it might have to get creative.

McMullan wrote in an email that profit isn’t the objective, at least for now: “Our primary focus is getting users on to the platform and optimizing their user experience.” Still, he seems to suggest other avenues that might one day turn into revenue: “Police departments, fire departments and emergency rooms are now starting to use Citizen as kind of an addendum to 911 alerts, since the dispatch will potentially be slower than Citizen,” he says. (This hasn’t yet happened in the Philly market.)

A Citizen app whose functions included decreasing response times and somehow preparing trauma surgeons for incoming patients might actually produce a net social benefit. But it’s hard to see how the app as currently formulated comes anywhere close to meeting that threshold.

That, in any case, is the view of Jones, the community activist. “The reality is,” he says, “I just don’t believe in the expansion of any type of technology that’s going to add an additional layer of surveillance on poor black and brown communities.”