Women Writers Are Driving Philadelphia’s Literary Renaissance

How a cluster of talented authors and one low-key but incredibly influential writing group called the Claw are making Philly a lit hotbed.

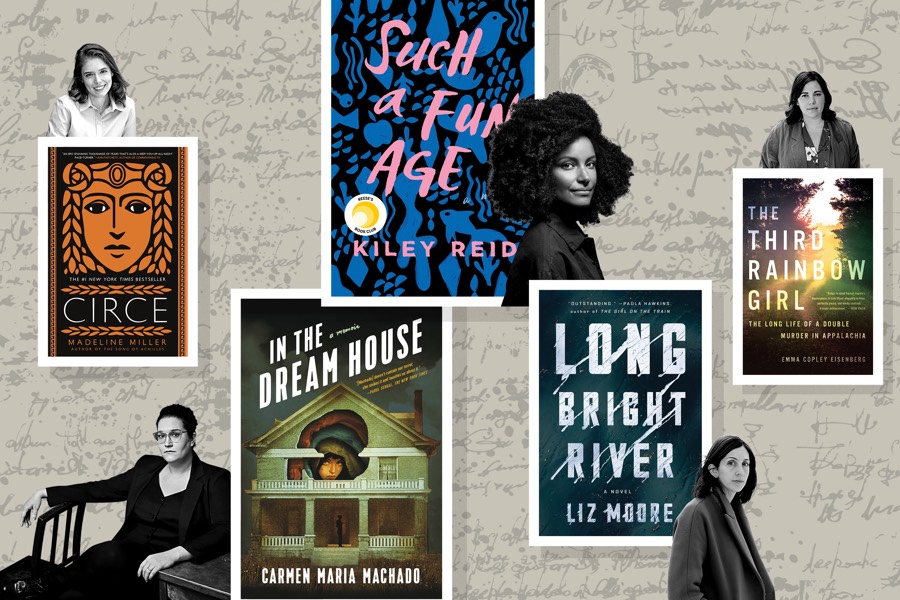

Some of the Philadelphia authors driving the city’s literary renaissance (clockwise from top left): Madeline Miller, Kiley Reid, Emma Copley Eisenberg, Liz Moore and Carmen Maria Machado. Photo illustration by Jamie Leary

Carmen Maria Machado is one of the country’s most celebrated contemporary fiction writers. A few years ago, she was catapulted into the national spotlight on the strength of her debut short-story collection, Her Body and Other Parties. But what she did next could prove just as momentous as her haunting, award-winning prose.

In the wake of her newfound success, Machado and Liz Moore, an English professor at Temple University and a fellow 30-something author, launched a Philly women’s writing group called “The Claw” (like New York City’s women-centric club and co-working space “The Wing,” Machado explains, but “sharp”).

The Claw is comprised of 19 published and professional fiction and nonfiction writers. Not unlike a book club, it meets roughly once a month, usually at one of the members’ homes. Over glasses of wine, the women ask for advice, offer feedback, and discuss what they’re writing at the moment — or just whatever’s occupying their minds.

“It’s really helpful to get together and talk about what we’re going through,” Machado says. “There are concrete things coming out of it, but for me, it’s a little more abstract. It’s about emotional support and having a place that’s inviting and friendly and welcoming.”

More than a writing group, the Claw is a support network. And the results of late are stunning.

A few months ago, Machado published her second book, a genre-bending memoir called In the Dream House that examines emotional and physical abuse in queer relationships in general but also chronicles a painful relationship she endured while earning her MFA at the University of Iowa. More recently — within the past month, to be exact — works by three other members of the Claw hit bookshelves and received stellar reviews: Liz Moore’s Kensington-set crime thriller Long Bright River; Kiley Reid’s novel Such a Fun Age, a Philly-centered meditation on race and privilege; and Emma Copley Eisenberg’s hybrid murder investigation/memoir The Third Rainbow Girl.

All this uplift is, without a doubt, contributing to a literary resurgence under way in Philly. As the city’s writers are garnering praise for new works, independent bookstores are popping up all over our neighborhoods: Amalgam Comics & Coffee House in Kensington (run by Ariell Johnson, the first black female comic-book-store owner on the East Coast); pundit and Temple prof Marc Lamont Hill’s Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books in Germantown; Shakespeare and Co. in Rittenhouse (with its steampunk-esque espresso book machine); A Novel Idea on Passyunk; and, imminently, Harriett’s Bookshop in Fishtown, whose owner, Jeannine A. Cook, describes it as if “black girl magic were a bookshop.”

When Harriett’s opens its doors on February 1st, plenty of folks are expected to turn out, as they have at other recent Philly bookstore debuts. But the buzz for this opening feels heightened: More than three and a half thousand people have indicated on Facebook that they’re interested in attending. Some of them are already buying Harriett’s merch.

Why the groundswell? I’d argue it’s because of the store’s mission to celebrate women: women authors, women artists and women activists. As Philly’s once-somewhat-diffuse fiction and nonfiction communities “coalesce,” as Machado puts it, writers and readers are beginning to recognize that women, by and large, are leading the way. They’re opening bookshops like Harriett’s, launching literary hubs, and publishing wildly popular titles.

Cook, Harriett’s 36-year-old owner (she’s also a writer and an educator), says it’s not a coincidence that “we’re seeing a huge surge of women on the New York Times best-sellers list.”

“Part of the reason it’s a great time to open Harriett’s is because of the polarization in our current society, especially around issues women are at the center of,” Cook says. “What you see in Philly’s literary community is that women have decided to take the lead here. A lot of women have decided to make our voices heard and start speaking up.”

A Demand for New Voices

Across the country, the publishing industry, like many societal sectors, has for too long been controlled by men who celebrate men. This despite the fact that in the United States, women read more than men. Historically, men have guarded their leadership of the country’s top-tier magazines, newspapers and journals, which have, unsurprisingly, predominantly represented male authors.

Since 2009, the organization VIDA: Women in Literary Arts has published reports on gender diversity in the U.S. publishing industry, tracking magazines like the Atlantic, the New Yorker, and Paris Review, and literary magazines like McSweeney’s Quarterly, Missouri Review and n+1. In recent years, it’s expanded its scope to include race, ethnicity, sexuality and disability statistics. When VIDA released its second so-called “VIDA Count” in 2010, tracking the then-binary genders of authors published in the nation’s most prominent publications, it lamented “the truth of publishing disparities.”

“We know women write,” VIDA’s Amy King said at the time. “We know women read. It’s time to begin asking why the 2010 numbers don’t reflect those facts with any equity.”

In 2018, VIDA celebrated a breakthrough: For the first time ever, none of the 25 literary magazines the organization monitors published fewer than 40 percent women writers. At last, the tides are beginning to turn, in no small part because of the demand for change.

It should come as no surprise that as our nation, like the rest of the globe, becomes more multicultural and connected, people expect a greater diversity of voices. Stories that illuminate untold truths generate change, foster communication and instill empathy. They mold the narratives we tell about ourselves, and those narratives play a role in the issues and people we prioritize. There’s a reason writers including Machado and nonbinary former Philadelphia poet laureate Raquel Salas Rivera were on this magazine’s “New Power” list last year: Their writing gives voice to people who have been dismissed by the mainstream literary canon and whose stories have gone largely untold.

In fact, the study of literature — the telling of stories — has always been ideological and “about identity and notions of the popular,” says Julia Bloch, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s creative writing program. In recent years, Bloch and her colleagues across the country have noticed a growing “appetite for new writing.” Students who enter Penn’s creative writing program often come “hungry for more representation of writers of color, women, and nonbinary and trans and queer writers,” she says.

Here in Philly, Bloch says, those writers happen to be producing the kind of writing that students seem “excited about” — science fiction, speculative fiction and experimental writing, which Bloch says provide authors with new forms through which to “give language to the kinds of experiences that have not been represented well in literary tradition.”

Philly has had previous moments when literary scenes united around a sociopolitical theme — and the city’s African American writers have often been at the forefront. The city’s poetry community has long been regarded as rich and robust, thanks in no small part to Black Arts Movement pioneer (and the city’s first poet laureate) Sonia Sanchez. Sanchez, who taught in Temple University’s English department for more than 20 years, brought such literary giants as Alice Walker and Ntozake Shange to Philly, inspiring the likes of our own Lorene Carey (whose first-ever play debuts this month). As for Philly’s science fiction, fantasy and LGBTQ scenes, Samuel Delany’s prose on sexuality, literature and society has held a place here for nearly two decades. (More recently in the fantastical realm, Madeline Miller’s Circe, a New York Times bestseller published in 2018, gave a new voice to one of Greek mythology’s most “unlikeable” female characters.)

Asali Solomon, a writer and Haverford English professor who grew up in West Philadelphia, says that especially when Sanchez moved here in the ’70s, Philadelphia served as a center of sorts for the nation’s “political and artistic energy,” particularly in African American communities.

“You think of all the majorly influential music that has been produced in Philadelphia, the richness of life here, the economic, spiritual and political differences … Philadelphia is a place where things have happened that have shaped national history,” Solomon says. “A lot of times they weren’t given coverage, but black writers kept those things in conversation.”

Nurturing the Next Generation

The Philly area is certainly home to some great male writers — Ken Kalfus, Solomon Jones and Tom McAllister, to name a few. But Haverford’s Asali Solomon, who’s also a member of the Claw, says she noticed a trend years ago while earning her PhD in English at the University of California, Berkeley: “It’s been my experience in writing and teaching that women are more likely to try and build community and work together more formally,” she says. “We try to go to each other’s events and support each other.”

Kiley Reid, whose Philly-set debut Such a Fun Age is about a young black woman wrongly accused of kidnapping while babysitting, moved to Philly in July and joined the Claw shortly afterward. While visiting the city on research trips for her book, she felt drawn in by the architecture, the food scene and the diversity: “Philadelphia is 40 percent black — I would love for my children to see people who look like them and don’t look like them.”

Reid says she hadn’t realized Philly’s fiction-writing scene would be “as big as it is. … When you move somewhere new, it’s pretty much the best offer [you can get], to hang out with other women in that city.”

The Claw and new bookstores like Harriett’s are far from the only places for writers to meet and support each other in Philly. MFA programs like those at Temple and Rutgers University, Camden (which fully funds its students), independent publishers like The Head and the Hand Press and New Season Books and Media, and intersectional literary publications like APIARY Magazine have also helped foster the scene.

A few years ago, Claw member and The Third Rainbow Girl author Emma Eisenberg created a new literary hub in Philly alongside friend and fellow writer Joshua Demaree, whom she met while working at the Penn Book Center in West Philly (now People’s Books & Culture). Eisenberg had noticed that while Philly’s poetry community seemed to be thriving, its prose community “could be a little fractured, or there could be many small scenes that didn’t always communicate.” She and Demaree thought up Blue Stoop, a literary home (without a physical home — for now) with the mission of connecting and supporting writers and readers in Philly via events, workshops and writing classes. Through a visiting writers series, the organization helped bring big names to Philly, including Alexander Chee, Emsé Weijun Wang, T Kira Madden and Kristen Arnett.

“The idea was to make a more public, accessible, open literary community where people could meet across lines of community and genre, and also to start classes so people could get better at the craft of writing, find mentors, and take the next steps in their career,” Eisenberg says.

What excites her most about Philly’s literary community is the young writers — in their mid-to-late-20s — who come out of Blue Stoop classes “figuring out how to be writers in the world right now.”

“I have a lot of empathy for that, because when I graduated in 2009 … there were no models,” Eisenberg says. Now, “There are just so many cool, talented people … from Philly.”

Machado says it’s not clear when she, Eisenberg, Reid and Moore will meet with other members of the Claw again; the foursome is busy touring the country right now. Someday soon, though, there will be another gathering. And for now, the group will remain open to only women and femme authors.

“Men take up a lot of oxygen in the room,” Machado says. “So much of my professional career is occupied by men’s presence. It’s nice to not have to worry about that.”