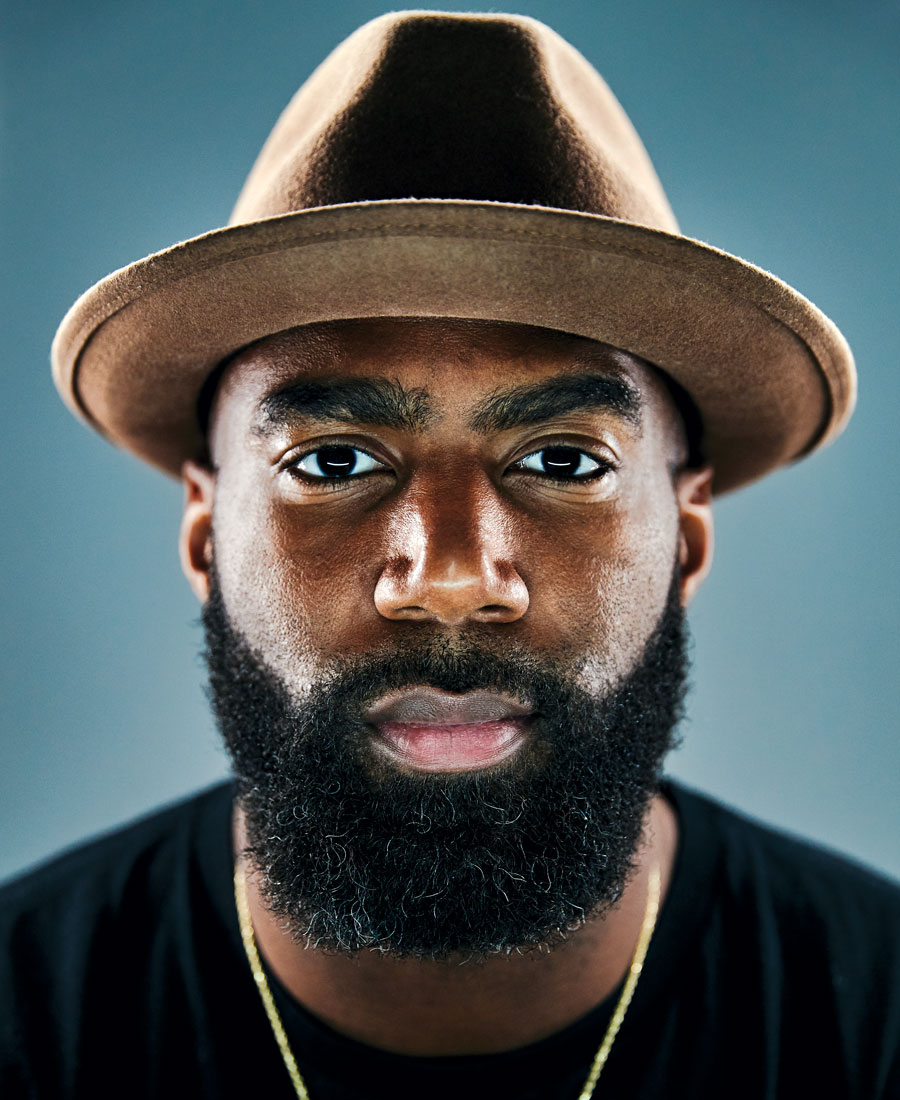

Eagles Leader Malcolm Jenkins on Race, Justice, and His New Filmmaking Career

This Malcolm Jenkins interview features a conversation about race, justice, his new film project, and what it means to play football in Philadelphia. Photograph by Jonathan Pushnik

Malcolm Jenkins is sore. “Two days after the game, it’s like when all your meds and stuff wear off,” he says, gingerly settling into a couch in the basement of Damari Savile, the Washington Square-based menswear store he launched in 2017. It’s the Tuesday after the Eagles’ disastrous loss to the Dolphins in early December, and Jenkins is doing what he does on his rare off-days during the season: attending to his multitude of outside-of-football interests.

Since arriving in Philly in 2014, the Eagles safety, who grew up in Piscataway, New Jersey, and played college football at Ohio State, has established himself as one of the team’s strongest leaders and best players — not to mention one of the NFL’s most interesting, outspoken and impactful voices. He’s established a foundation that works with kids in various underserved communities. In the wake of Colin Kaepernick’s national-anthem protests, Jenkins raised a fist at Eagles games and co-founded the Players Coalition, an activist group that ultimately helped secure nearly $90 million i funding from the NFL for social justice causes. He’s spoken out about policing in black and brown communities, most recently authoring an Inquirer op-ed, published in November, calling for changes in the Philadelphia police department.

And now Jenkins, 32, is entering a new realm: film. He’s the executive producer of a forthcoming documentary called Black Boys, directed by white filmmaker Sonia Lowman, that will be featured at the SXSW Film Festival in March. He’s also co-founded Listen Up Media to produce other projects. Though he’s aggressive on the field, Jenkins is soft-spoken and thoughtful off of it and willing to talk about everything from the challenges that black men in America face to the love he still has for football.

You’re already involved with so many things. Why add moviemaking to the list?

It really started — I was writing a weekly column for a publication. It was right around when Trump called Omarosa “a dog.” And I wrote this piece about women in general — but especially black women — about the rhetoric that has always been used around them, comparing the word “dog” and how it’s synonymous with the word “bitch” and how that’s used throughout rap culture and all these different things. And while we can get upset at Trump, it made me take an introspective look at how I grew up and how society as a whole views black women.

Long story short, they didn’t want to publish the piece. Which is weird, because I wrote about a whole bunch of other things and they had no issue. And so that was kind of frustrating. That was the first time I wasn’t able to get my voice out there, and soon thereafter, Sonia Lowman contacted me to be part of the film she was doing, Black Boys. [Initially] I just came on as an interviewee, but I became really intrigued by her motivations for doing it — a white woman making a film about the spectrum of humanity of black boys. And the more I spoke with her, the more interested I got in the piece, and I was able to come on as an executive producer. And right around that time was when we started Listen Up, just as a way to control my own narrative, do storytelling about things in society that are going on, whether it be social justice or just being able to own the narrative of the black experience in America.

We worked really hard with Sonia on Black Boys and feel really confident about it. And we’re also part of a film called First Day Back. It’s a fictional story about the first day back after a school shooting here in Philadelphia.

In the past 15 years, media has gotten away from assuming there’s one monolithic narrative about things. There are a whole bunch of narratives that need to be told.

I think there is a need to show other narratives. But one of the things that happens is, you have the stories of minority groups being told by non-minorities. I think history has shown us that it’s hard to be responsible with someone else’s history or someone else’s experience or perspective. I think it’s important that that representation is there — that those narratives are correct and are told by those who live it.

How much does Black Boys resonate with your own experience?

As a film, it does a good job of painting the reality that there’s a broad spectrum of humanity when it comes to black people, especially black boys. We’re not monolithic. But it also shows how our bodies have been a commodity and have been used, and our minds completely disregarded or not acknowledged. Our creativity. Our love. And what it does to black men and black boys when you walk around in a society that fears you, and what kind of damage that does to you.

What intrigued me was that Sonia was trying to really pull on the heartstrings of white people and how they need to see themselves as part of the problem — or the necessity for them to be part of the solution. Growing up, she was on the right side of history; she didn’t have a racist bone in her body. Her parents are very, very liberal; they marched for civil rights. But she said once she got to her early 20s, she realized she had this unexplained fear of black men, and she didn’t know where it came from. I think she realized that society has kind of conditioned her. It’s not about your parents teaching you to be racist. It’s what you see in front of your classrooms. It’s what you see on TV. It’s what you hear.

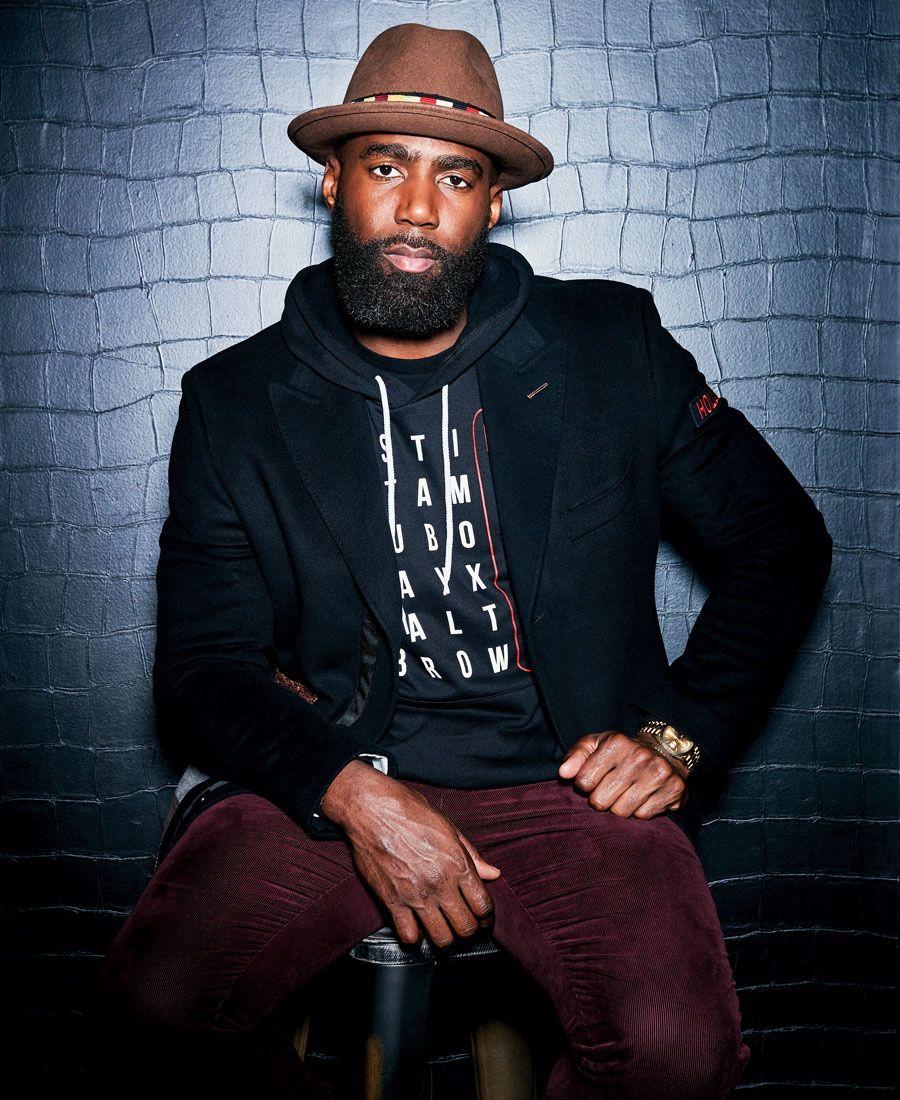

Photograph by Jonathan Pushnik

You’ve been doing things outside of football ever since you were a student at Ohio State. Why is it so important to you to do more than just play football?

I recognize that I’ve gotten to a place in life because people have nurtured all these different sides of me that had nothing to do with football. Football is the easiest part of what I do. But being able to have people talk to you about integrity and leadership and how to give back — I think it’s important that we give other people the same kinds of opportunities. When I look at my foundation and the work we do in communities, we come across some really talented and remarkable children that society doesn’t really value, either because of the zip code they live in or the school they go to. And we recognized, too, that we don’t need to teach them how to be great. We need to move things out of the way, because they already are.

For me, a lot of it starts with vision. That’s the biggest thing people have given me — people who implanted visions of myself in me. I never thought I could play football professionally until I had a coach who every day told me, “You’re gonna be in the NFL.” I never thought I’d be able to speak publicly until I had a person constantly telling me I could.

Before you can dream, somebody has to tell you what you can dream about.

That’s one of the interesting things abut Black Boys. There’s a principal here in Philadelphia who’s in the film, and he talks about this concept of windows and mirrors. In most cases, there’s a difference between a white kid’s experience and a black kid’s experience. I can tell a white kid, “You can be whatever you want to be,” and they can believe it because they’ll look at any profession and they’ll see white people not only in the profession, but at the top. If you see it, of course you can do it. But telling that to a black kid when a majority of your teachers — I think it’s like two percent of educators are black men, so you don’t see yourself in front of the classroom. You don’t see yourself as a principal. You don’t see yourself in all these high-ranking things. And so when someone tells you you can be whatever you want to be, it’s really hard to fathom that as a young kid.

It’s one of the reasons we started Listen Up — to be able to showcase these different things, so people have references to see themselves in ways that haven’t really been portrayed thus far.

A lot of people have ideas. It seems like you have ideas and then you go ahead and do them. Either there’s no fear, or you just ignore the fear.

The only way that you can figure out, really, your purpose for being here is to try things. If it fails, then it wasn’t meant to be, and there’s lessons you learn along the way.

Let’s talk about the NFL and social justice. What was your reaction when Colin Kaepernick first started protesting during the national anthem in 2016?

I remember getting asked about it. It was right after a preseason game, so I didn’t get the chance to see it, and they were asking me about it. Nor did I get to hear his quotes. But once I got a chance to hear his reasoning and why he did what he did, I thought it was very powerful. And it sparked something in me, because I had been having those same convictions and ideas probably like a month or so before, in July, after the passing of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. A few weeks after that, I arranged a meeting with former police commissioner Richard Ross and some community members, and we were talking about policing here in Philly. And a few weeks after that, that’s when Colin Kaepernick knelt. So I knew there were other guys who feel just as passionately as I do about these issues. So that was encouraging.

It’s amazing how successful Kaepernick was, just from the perspective of protest as an art form. The point of a protest is to draw attention to an issue, and what all of you guys did has definitely done that.

Definitely. That part was completely mission accomplished. I think the hardest part about that whole thing was keeping everyone on topic. Because it quickly became about the anthem, about the flag, about the military — all these things. And keeping the focus on the issues — marginalized communities, lack of education, police brutality, all these things. You want people to stay right there.

You and Anquan Boldin co-founded the Players Coalition in 2017 to bring attention to racial injustice. When you first started to have conversations with NFL owners about the issue, did they get it?

Uh, no. And honestly, I think the majority of them still don’t get it. But they don’t have to, in my book, to get this thing right. This has always been a players-driven kind of a movement. I don’t really think it’s the owners’ role to get it and act upon it. I think it’s their role to facilitate and not impede what guys are trying to do. I think a lot of them recognize that it’s important and acknowledge that it’s there. But are they willing to step in front of the issues? I doubt it. I think it’s hard, in one or two sit-down meetings, to have someone who’s a billionaire owner of a football team, never came from that background, understand the plight of what’s going on in society in a way that makes them want to put everything on halt and jump out in front.

But one of the important steps that we did do is to try to at least educate them first on what’s happening. So here in Philly, we took Jeff Lurie and [NFL commissioner] Roger Goodell on kind of a listen-and-learn tour, where they met with grassroots organizations that were able to talk to them about the struggles of people coming in and out of the criminal-justice system. We went down to court and watched bail hearings. And you start to look at the discrepancies of who gets what kind of bail, and you’re able to talk with the police and kind of understand the struggles of policing in the city. So really, just a 360-degree view: These are the things that we’ve learned, these are the things that we’re trying to get accomplished, so that when you see a player taking a knee or raising his fist or doing whatever, you understand that this is what we’re referring to, and it’s not anything to do with the flag or the military.

At least from the outside, it seems like Jeff Lurie has an open mind.

Yeah. I mean, he’s definitely one of the NFL owners who have been, I think, allies, and he at least understands and acknowledges those issues and has done nothing to get in the way of the thing that we try to do. And he’s had, obviously, a really loud and vocal locker room over the last couple of years with multiple guys, not just myself. And it’s not that way around the league.

Photograph by Jonathan Pushnik

After the Players Coalition got the NFL to commit to an $89 million social justice partnership, you and Eric Reid from the Carolina Panthers, who’s a close friend of Kaepernick’s, got into an altercation before a game, and afterward, he called you “a sellout.” He was upset that you agreed to stop protesting during the anthem and also that Kaepernick hadn’t gotten his due. Did you understand where he was coming from?

I usually don’t comment on it, because I never want the dialogue to be about him and me disagreeing and not about what we both agree on — and that’s that we need to change things in our society, especially with black and brown people. I respect his view — him and Colin. This is not an easy subject, not even for black and brown people.

Do you think Kaepernick will ever play in the NFL again?

The more weeks that go by, the less the likelihood is of him being in an NFL uniform again, but I really hope so. I know I’ve been trying to convince different teams to sign him. I think he deserves it, and I think at this point, everybody recognizes that it has nothing to do with his arm talent or him as a quarterback. I think it’s an unfortunate situation. But I also think it cements his legacy for what he’s sacrificed and what he was willing to put on the line to make a stand, to disrupt the status quo.

Are you guys in touch?

No. No.

Your activism is interesting. You’re willing to say what you think and call people out, but you also work hard to understand the other side. Why is that your approach?

My dad always told me: You don’t know what you don’t know. I wouldn’t want anybody to judge my community without understanding my community. And so I want to afford that same process to any other community I don’t know. So when we’re talking about policing and law enforcement, I know very well what the complaints of black and brown communities are. But what I don’t really know is what it’s like to be a police officer. What is the training? What is the culture like? I want to know. So I ask, and I have those conversations because I think, especially with the rise of social media, everybody’s kind of picking their corner — you say one thing, I have a counter-argument. And we’re really not listening. We’re just trying to figure out who has the best lines, and we’re not getting anything accomplished. In fact, it usually makes things worse. You’re further divided, which means that there’s a greater chance of fear, and when people are afraid of each other, bad things happen.

Have you learned things about policing that you didn’t understand before?

I know that there are really good cops out there; there are police officers that want to serve their community, that want to do the right things. But especially in certain cities — this being one — there’s a toxic culture. And in a lot of policing communities, there’s a lack of understanding of the history of policing in black and brown communities and what that badge means. It’s less about this person as an officer and more so what your uniform represents to my community. It’s the generations of trauma at the hands of the police.

Have you felt that trauma yourself? Are there incidents you’ve dealt with personally that have shaped how you think about this?

To me, one of the largest things is just over-policing, and so just constantly feeling like you’re being the target. When you have departments or cities that practice stop-and-frisk, the racial disparities in that are ridiculous. When it comes to officers being able to say who looks suspicious, it’s usually black or brown people. When you look at all of these tactics about how to reduce crime, they usually have these racial disparities. When you look at all the studies, it’s like — white people commit crimes at the same rate or at similar rates as black people. So why are there these disparities? And I think that over-policing, on top of, like I said, the historical context of how we got here with policing — it’s a cycle, you know? Where there’s no trust. On either side. And so things like simple traffic stops become huge issues. When people are afraid of each other, bad things tend to happen.

John McNesby, the president of the FOP, had a pretty Neanderthal response to the op-ed you wrote in the Inquirer, calling you a “non-resident washed-up football player” and basically telling you to mind your own business. Is that discouraging?

No, I think it proves the point. Honestly. It just showcases what I’m talking about. When I did a ride-along, we had to respond to a shooting. Which I was not expecting. So we show up, and there’s 10 to 12 officers in the middle of the street in a huddle talking to each other, and all the residents are either within their gates or on their porches. And the police officers are frustrated, saying nobody’s cooperating. The people who live there don’t trust that the police will keep them safe, so they’re not saying anything. And so it was … a very tense situation. But I can’t imagine how we can go about fixing that if, when the community talks about the things they want to see out of policing, the response is what we just saw. How you rebuild trust or gain any kind of commonality or common ground — it’s almost impossible if that’s the first response.

Even one of the officers I rode with, I was very surprised when I asked him about the protests and things around the country: Do you feel like there’s an issue with police brutality, or are people making noise for no reason? And he said he didn’t think there was a problem with police brutality; he thought there was a problem with people’s behavior. It just showed me that even as a law-enforcement officer, he doesn’t understand the disparities of his own practices.

There’s gonna be a difference between if Carson Wentz gets pulled over and if I get pulled over. I don’t want to say [Carson] won’t have a care in the world, but I don’t think he’s gonna be worried. Me? I’m petrified.

So I asked him — I said, there’s gonna be a difference between if Carson Wentz gets pulled over and if I get pulled over. And the difference may not even be you. It may be the fear that Carson has vs. the fear that I have that will cause you to react differently. I don’t want to say [Carson] won’t have a care in the world, but I don’t think he’s gonna be worried if he gets pulled over. Me? I’m petrified. We want to act like we’re past this racial divide, we’re past racism, but we’re really not. We had our black president; all things are well. And it really isn’t.

McNesby was obviously playing to a specific constituency.

Yeah, he’s the president of the FOP. What that tells you is that there’s a faction of people he’s pandering to. And it’s not surprising. That’s how things continue to be repeated. We might find common ground here on the street, but those in power keep things the way they are.

We’re at an interesting cultural moment. On the one hand, there’s a lot more conversation about social justice. On the flip side, there’s Trump and the reactionary right and people going to extremes on that side. How do you reconcile that?

I feel like every action has a reaction. Those who want to change society will be met with equal force by those who want to keep it the same. The closer we get to change, the more divided I think we’ll be. It’s not like racism is the only thing holding all of this apart. There’s a lot of money and interests involved in why things are set up the way they are. In a capitalist society, there’s always gonna be people that have and people that have not. And when you’re the majority, you’re gonna make sure that your people are the ones that have. Or at least, if there’s gonna be people that have not, it’s not gonna be us.

I think when people talk about privilege — that’s more so what we’re talking about. And it’s hard to get people to give up their own privilege to bring somebody else along. It’s hard to get somebody to take a step down to give somebody else a step up. And so that’s what we mean when we talk about equality. To bring everybody closer to the middle. That means somebody’s losing something, somebody’s gaining. And it’s almost like, like I said, the closer we get … when those changes become inevitable is when people are really the most polarized.

What kind of reaction do you get from fans these days?

Honestly, I’ve never gotten a bad comment. Everybody is like, I love what you do on the field, but even more so what you do in the community. I get talked to about things in the community more than football. I’m honored [by] that. Football is great, and I love it and I want to be a legendary player, but at the end of the day, it’s a game, and there’ll be other players who play it at a higher level than I do. The real impact is obviously in the community — real lives, real people being touched.

In terms of the Eagles, it seemed liked there was amazing chemistry on the Super Bowl team. Was that just luck?

I think there’s a little luck in there. But it takes time and the ability to build a culture. When Doug [Pederson] first got here, we were — I think we had a losing record. But I think we all felt like we were just a couple of pieces away from really being a solid team. And then the next year, we won the Super Bowl. What everybody kind of assumes is that, oh, once you have a championship-caliber team, that just stays. But the hard part about maintaining success in our league is that your locker room turns over 30 percent almost every year. So here we are, three years removed from this championship season, and the team is totally different. Totally different. LeGarrette Blount was a two-time Super Bowl champion — lost. Chris Long, a two-time Super Bowl champion — lost. A bunch of guys that were integral in creating a culture. So not to say all is lost, but it’s not the same team as 2017.

How aware are the guys in the locker room of the impact the team has on the emotional life of the city?

I think we very much understand it. And I think we carry that burden as well. Losing here is a lot worse than losing anywhere else, I can tell you that.

How much longer do you think you’ll play?

I don’t know. I want to keep playing. I mean, my body feels good. I’ve been healthy. I’ve accomplished a lot in the game. But I think I am to the point where I am finding other talents that I have, and I want to explore some of those different things. But there’s nothing quite like running out into the stadium. I’m happy where I am. I told myself a long time ago I’d make it to 10 years, then every year after that would be year-to-year. This is my 11th season that we’re finishing up. And so we’ll see if I feel healthy at the end of the year. And keep going.

You have no shortage of things to do after football.

Yeah, I got plenty of things lined up if I ever want to walk away from the game. But I’m having a lot of fun playing. The minute the game stops being fun is when I’ll probably hang it up.

Have you thought about politics as a next step?

People bring it up all the time. But I don’t think I’m interested in it. I don’t like playing politics. [laughs]

You might be too honest.

Yeah, a lot of politics comes down to money. You need money for a campaign and all these different things. And then you end up kind of being a slave to whoever funds you. And that’s the game of politics. I’m not really interested in that. I think I serve a better purpose just using my voice, my influence and my leadership in the way that I have been.

Published as “Malcolm Jenkins Would Like You to Listen Up” in the January 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.