In “Assault on Privacy,” Philly Police Routinely Reveal Mental Health Status of Missing City Residents

Police say it’s vital information for the public to know. Medical ethics experts say otherwise.

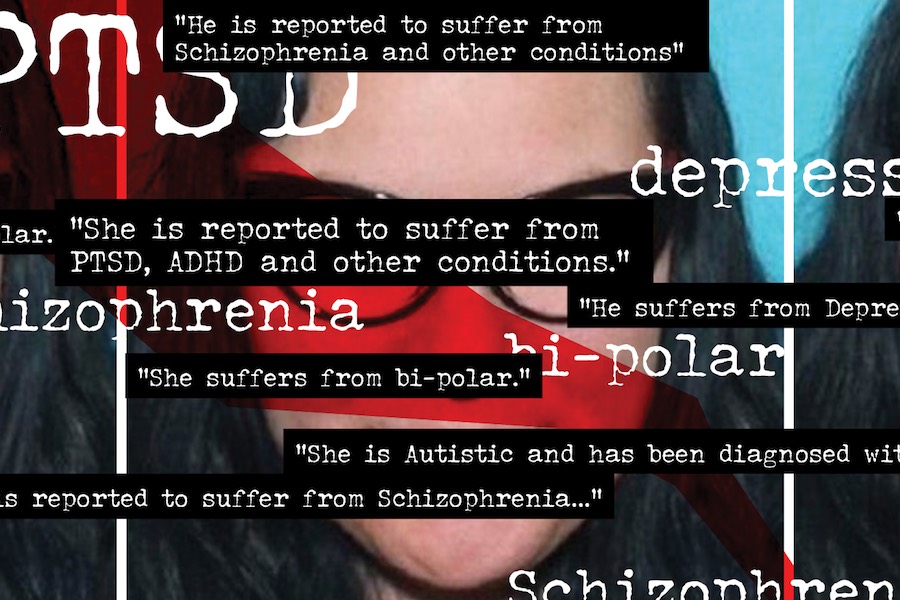

Background: South Philadelphia resident Christine Veasey in a photo released by police after she was reported missing last April. Foreground: Actual quotes from missing person alerts publicly released by the Philadelphia Police Department.

As far as Google was concerned, South Philly’s Christine Veasey was a relatively anonymous person a year ago. Back then, a quick search on her name would have yielded a link to her Facebook page and a brief mention in an Inquirer human-interest story. But by late April, the world’s largest search engine had new information in its dossier on Veasey thanks to the Philadelphia Police Department: Veasey was bipolar.

Veasey’s mother reported her missing on April 29th. The two of them live together in the Whitman section of South Philadelphia, and Veasey hadn’t been home or in contact with her mom for three days.

When her mom filed a missing persons report, she told the police of Veasey’s diagnosis, but she says she only gave them that diagnosis as background information. She didn’t intend for police to release the bipolar diagnosis publicly.

But that’s exactly what happened.

On April 30th, the public affairs unit of the Philadelphia Police Department sent out a press release to numerous media contacts and published a public blog post that included her photo, a full description, and a line about her bipolar diagnosis.

That post was shared scores of times on Facebook and Twitter. And, just like that, the fact that Veasey was bipolar was no longer a private medical matter between her, her doctors, her family, and close friends. It was out there for all of the world to see.

Veasey returned home after being gone for a total of five days, and it was shortly after this that she saw her face and mental health status plastered publicly on the Internet.

“It just wasn’t right,” says Veasey of the police department’s decision to share her diagnosis. “What’s important is that I was missing and endangered. You don’t need to know exactly what is wrong with somebody. You don’t need to know their diagnosis.”

Veasey explains that she had recently experienced significant losses in her life and that she had been under a lot of stress. She also wasn’t taking her prescribed medications correctly, but she adds that her therapist isn’t even sure that the bipolar diagnosis, which she received from a previous doctor, is correct. In any event, Veasey insists that she was never a danger to herself or to the public.

It turns out that the handling of Veasey’s case is standard operating procedure in Philadelphia.

“It Will Follow Them Wherever They Go”

A Philly Mag investigation has revealed that the Philadelphia Police Department has been publicly sharing diagnoses of mental illnesses in press releases and blog posts about missing persons — keep in mind, we’re talking about people who haven’t broken the law here — since at least 2013. A police spokesperson wasn’t sure exactly when it started.

While some police departments around the country share similar information on occasion, Philly Mag couldn’t find a police department in a major metropolitan area that publishes the information anywhere near as routinely as happens in Philadelphia.

In the last six months, the Philadelphia Police Department has announced a total of 94 missing persons — the vast majority of those were quickly located — listing specific diagnoses of mental illnesses for 30 of them, or nearly one-third. Those diagnoses included depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizophrenia.

Many of the missing persons reports shared by police also make it to the large audiences watching local TV news. That’s great in one sense, since the whole point of a missing persons bulletin is to ask for the public’s help to find somebody, but when the bulletin includes a mental health diagnosis, the broadcast also reveals that diagnosis to the viewers. And many of those TV news reports also become articles posted for all eternity on the TV stations’ websites. We found many dozens of local examples.

The end result of all of this is that when you google the name of somebody whose mental illness diagnosis appears in a missing persons report, the first search result is often a link to the blog post by the Philadelphia Police Department or a news article referencing the department’s information. In some cases, these police posts include the name and face of a child.

“This is a fundamental assault on privacy,” says Dominic Sisti, the director of the Scattergood Program for Applied Ethics in Behavioral Health Care at the University of Pennsylvania. “It will follow them wherever they go, and it is stigmatizing. You say schizophrenia and most people still think that the person has ‘split personalities.’”

Sisti points out that while telling the public what the missing person was last seen wearing and how tall they are might help somebody spot the individual, telling the public that the person is schizophrenic or bipolar will not.

“It’s just an anachronism from times gone by where this is essentially code for this person may be dangerous,” he adds. “It’s a dog whistle about violence and danger which is not empirically true, statistically speaking. This points to our false beliefs about individuals with mental illness. But a person with schizophrenia is no more violent than a person without schizophrenia, and, in fact, the person with schizophrenia is probably more vulnerable to being victimized.”

Sam Knapp, director of professional affairs for the Pennsylvania Psychological Association and author of dozens of papers and books on the ethics surrounding psychology, agrees.

“How can you tell if somebody is schizophrenic or bipolar when seeing them on the street?” Knapp asks. “Maybe there is some weird, isolated situation where it is relevant, but routinely releasing the diagnosis definitely isn’t the way to go. This is the type of thing that most people want to keep private, and there is harm when it gets out.”

Both Sisti and Knapp suggest that describing a behavior that’s distinctive to the person and that may be related to their mental illness would be far more helpful than listing a diagnosis.

“Perhaps, in some cases, it would be worth saying something like, ‘People approaching this person should know X, Y, and Z’,” Sisti says. “Maybe they should be approached in a certain way that a family member would be aware of. That’s potentially helpful. But saying somebody has schizophrenia or is bipolar is not.”

“It’s a Fine Line”

We reached out to the Philadelphia Police Department to find out why they insist on revealing these diagnoses in missing persons reports.

“It’s a fine line,” says Philadelphia Police Department spokesperson Sergeant Eric Gripp. “We don’t want to stigmatize anybody. But we also want to notify the public of a condition that might be a potential threat to the public. We also want to do everything in our power to give identifiers for those missing people. Sometimes their family members or friends are so concerned. They fear that they are going to kill themselves.”

Gripp says that his office will delete any missing persons posts — and says they have before, though he’s not sure how often it comes up — if the person is found and if they or a family member makes a request. (The public affairs office can be contacted via email at police.public_affairs@phila.gov.)

In fact, the public affairs office deleted the post about Veasey on Wednesday afternoon after being contacted that morning by Philly Mag and Veasey’s father, a former Philadelphia police officer.

In light of the deletion, we asked Veasey if she’d prefer to remain anonymous in this article. After all, the original source of the concern is, in theory, “gone.” But the cached version lives on and the police alert also shows up in a background check, the same type that a prospective employer, landlord, or just nosy person might one day use.

“I have real concerns about how this information might be used in the future, if it’s found out of context,” Veasey tells us. “So I’d rather come forward and tell my story and also give a voice to other people whose personal lives have been exposed. What is going to happen when our boss finds it? What is going to happen if we need to rent an apartment? What if I want to try dating in the future? Yo, this chick is crazy! But I’m not. And it’s none of anybody’s business.”

Research assistance by Cara Heenan.