Philly’s Latest Literary Star Has a Second Book Out This Week

We talk with Carmen Maria Machado about her haunting new memoir, In the Dream House.

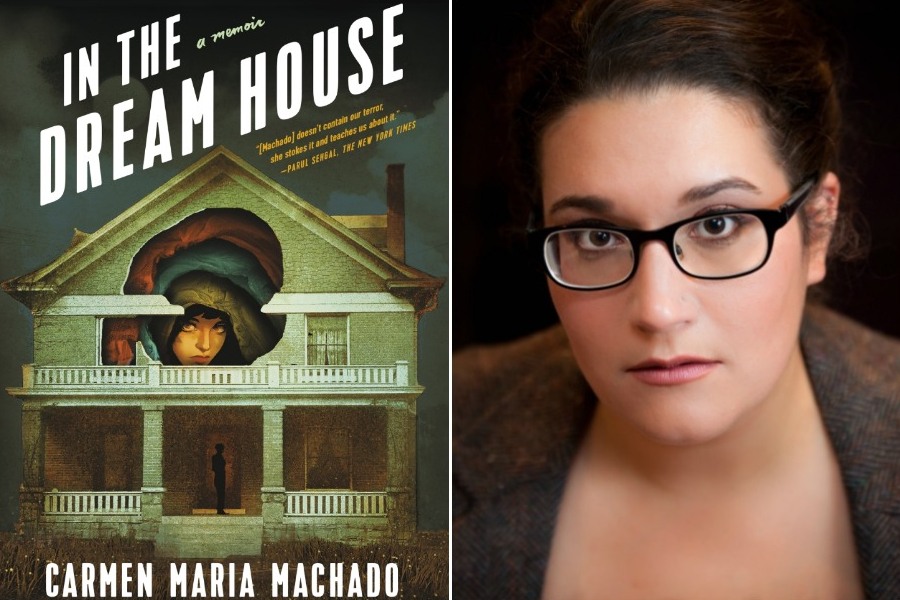

L: Image courtesy of Graywolf Press | Carmen Maria Machado by Tom Storm Photography

One of Philly’s most distinguished modern writers, Carmen Maria Machado, has a second book out this week.

The 33-year-old Penn professor’s memoir, In the Dream House, has been published by Graywolf Press to critical acclaim. Its release comes two years after Machado’s first book, a short story collection titled Her Body and Other Parties, became a finalist for a National Book Award and earned dozens of other accolades. (The collection is also currently being made into an FX horror series.)

In the Dream House chronicles an abusive and volatile relationship. Machado’s story is recounted in fragments that span genres and elude classification. Some chapters offer sharp, deeply personal snippets of her life — traumatic conflicts with her controlling and sometimes unpredictable partner — while others, in essay and nonfiction form, attempt to place her story within a larger (and, as she stresses, lacking) framework of domestic abuse within queer communities: “I enter into the archive that domestic abuse between partners who share a gender identity is both possible and not uncommon, and that it can look something like this,” Machado writes in the book’s second chapter. “I speak into the silence. I toss the stone of my story into a vast crevice; measure the emptiness by its small sound.”

We caught up with the West Philly writer (who will speak in Camden on November 15th) to hear more about her latest work.

How’d this book begin?

I was working on it for quite a while, picking away at it. It was always really bad. A couple of years ago, I was in Iowa City [where the book partially takes place], and at some point I thought to myself, “What if I try to tell this story as a haunted house story? What if I tell it as if it were a bunch of different stories?” As soon as I had that idea, the whole book sort of changed me. In early 2017, I sold an early draft to Graywolf and then expanded it. The haunted house idea came first. The non-memoir bits, the essays and the historical aspects came much later.

In the first section of the book, “Dream House as Overture,” you call prologues “tedious” and suggest that paratext implies that an author has something to hide. You then move onto “Dream House as Prologue.” Why start this way?

When I first read a draft of the section that was “Dream House as Prologue,” I really loved it. While I was working on this project, one of the hardest parts was writing the non-memoir parts. I didn’t have a lot of experience in turning research into good, interesting, readable prose. I had all these non-personal, fact-based pieces, and I would read them aloud to myself, and the prose would die on the page. The prologue section was the first [non-memoir section] that I wrote when everything came together, and I was like, “It’s establishing the terms of the book.” My editor loved it but pointed out that it was interesting to open a memoir with someone else’s words. So I thought I could start the book on my own terms [with “Dream House as Overture.”] [With the paratext], the biggest part of this for me was getting the reader to understand destabilization, and what it was like in that space. I liked the idea of opening up the book with a challenge.

How’d you make the decision to include some chapters in second person and others in first person?

When I initially sold the book, it was mostly very personal and entirely in second person. I sort of did that by accident. When my editor bought it, he was like, “We’re going to come back to it in a year and a half, and when we come back, I want to make sure you’re engaging with it deliberately, and [second person is] not just a distancing technique.” A year later I was revisiting it … There were pieces that I wrote that were intense and traumatic, and writing those felt like living it all over again. I thought, “I can put those pieces in second person plural, in an eternal hamster wheel. It’s going to implicate the reader, and it’s a way for me to engage with my past self.” I came to it in this backwards way, but it all worked out.

You talk about “archival silence,” or a “difficult truth” that “sometimes stories are destroyed, and sometimes they are never uttered in the first place; either way something very large is irrevocably missing from the archive.” How did a lack of documented stories about abuse in queer relationships affect the making of this book?

I talked in the afterword about some of the work I did encounter in writing this project. Even now, I’m currently re-watching Law and Order: SVU, and I saw an episode last night that involves a brief subplot about gay domestic violence. I think I’m always going to be encountering the thing I missed or the thing I forgot. That being said, there were a handful of very helpful and useful essays that helped me get a lay of the land. But it was hard to find that material. I was like, “Certainly there’s some documented historical material,” but I struggled. Even the idea of an abused person is relatively new. Also, I’m not a historian. As I was [researching], I was like, “Man, I wish an actual historian was doing this.”

How might this book change the life of a young adult, queer or otherwise, who reads it today?

I hope it gives people context for their own experiences. Insofar as I had no goals that involved other people, I can’t say to you — a stranger, who is separate from me in every way — what your experience is like. But I can tell you what happened to me, and maybe what’s happening to you is similar.

Did you have any qualms about writing about something you were so close to, especially considering your wife, Val, is a strong figure in this book? How might the “archival silence” have outweighed that hesitation?

I don’t know if hesitation is the right word. I certainly had to have a really intense conversation with myself. But honestly I felt like, with this book, it was about getting it out of the way. This is the book I have to get off my chest. It’s not like this happened so recently; it was seven years ago. Even though I had some anxiety about it, and part of me is like, “I wish I hadn’t had to write the book,” I’m glad it’s done.

Are you still working through what happened, or did writing the book give you a sort of closure?

I don’t think that the purpose of writing a book like this is closure. I wanted to write a beautiful piece of art about something that happened to me. I think my own relationship with the material is unfinished, as so much of our lives are.

You recently helped edit Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2019. What was that experience like?

It was really delightful. John [Joseph Adams] is very professional, and he just gave me 80 stories that I then had to whittle down to 20. It’s a real gift to have the opportunity.

And how’s Philly life been treating you?

I love Philly. We just bought a house in West Philly. I feel like I’ve really come into my own in Philly, and I’m really grateful for the community here.