A Look Inside Temple’s New $175 Million Charles Library

The library, conceived as a public space as much as one for academic research, is instantly the most beautiful building on Temple’s campus. One trade-off: Most of the traditionally open book stacks are now a robot-only domain.

An entrance to the new Charles Library at Temple. Photo by David Murrell.

When it came to planning the new Charles Library at Temple University, there was a particular problem Joe Lucia, the school’s dean of libraries, had to solve: what to do about the books.

See, it turns out all those tomes take up a good deal of space, which is why many libraries are nothing more than fortresses of shelves. But Lucia wanted something else: a building that at its core is still an academic research library, but one that also retains enough open space for classrooms, public events, and just plain old milling about.

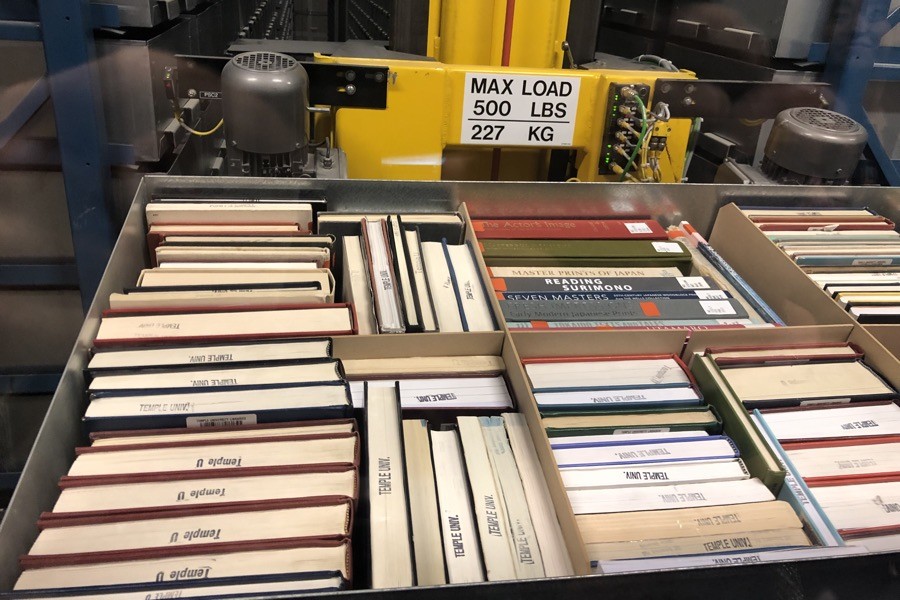

The solution Lucia came upon is one that is both largely out of sight and also the organizing principle of the entire $175 million, 220,000 square-foot building. Its name is the “automated storage retrieval system,” and it takes the form of a concrete vault in the back of the library, which looks like a nuclear doomsday fortress but is in fact where about 1 million (some 80 percent) of the library’s books are stored — all on 50-foot high, floor-to-ceiling racks, accessible only to a book-finding robot. Lucia says the ASRS, or “book bot,” as it’s known, is about 10 times more efficient than other types of shelving.

Now Lucia had space to work with, and with the Norwegian architectural firm Snøhetta, the two set about designing a space that looks more like a concert hall than a library:

The atrium at Temple’s Charles Library, so named for the $10 million gift that came from philanthropist and Temple grad Steve Charles. Photo by David Murrell.

The view from the second floor. Photo by David Murrell.

Where there might once have been books, there are now students. Photo by David Murrell.

The building’s exterior, all glass, granite and cedar, is nothing to scoff at, either:

Photo by David Murrell.

But the automated retrieval system — one of the largest such systems in any North American library — is the perhaps the single most interesting innovation. It essentially works likes this: A student requests a book online. A robot jumps into action in the concrete vault and delivers an entire box to a waiting (human) librarian. The librarian then finds the relevant book, places it on a collection shelf for students, and then the robot shoots off once more to return the box to the shelf. Check it out:

Books retrieved by the robot are then delivered to human librarians, who deliver them to students. Photo by David Murrell.

But the delivery system raises an existential question: What is a library for, if not for browsing and exploring books? Any professor can tell you stories about searching for one book at a library, only to stumble upon an even more useful one on the very same shelf. That method of serendipitous inquiry is dead with book bot.

“We’ve heard that a lot,” says Lucia. But to fit all the library’s books on site with compact shelving would have required anywhere between 60,000 to 80,000 additional square feet of space. “A space that much larger we couldn’t afford,” he says, while noting there still are 200,000 browsable books on the library’s top floor — mostly a collection of recent scholarly work, as well as certain oft-requested volumes.

The fourth floor is one of the few areas in the Charles Library that actually looks like a typical library. Photo by David Murrell.

Setting aside those heady questions … here’s the library’s top floor, home to one of its best assets: a rooftop patio and garden.

Photo by David Murrell.

Photo by David Murrell.

The green roof, which is meant to help curb stormwater runoff, is part of the library’s plan to apply for LEED Gold certification. In keeping with that eco-friendly philosophy, the building has hardly any charging outlets. Instead, students can check out portable laptops or portable batteries for their various devices. So far, the kids have yet to revolt.

After all, how could they? The library is undeniably beautiful. And here’s the best part: In keeping with Lucia’s vision of a library that’s not just meant for academics, the building is open to the public. Which means you can check out all of the architectural splendor above for yourself.