That Super-Stinging Jellyfish Is Popping Up Along the South Jersey Shore

The clinging jellyfish has previously been spotted north of LBI. But a recent discovery suggests the reach of creature’s tentacles is expanding.

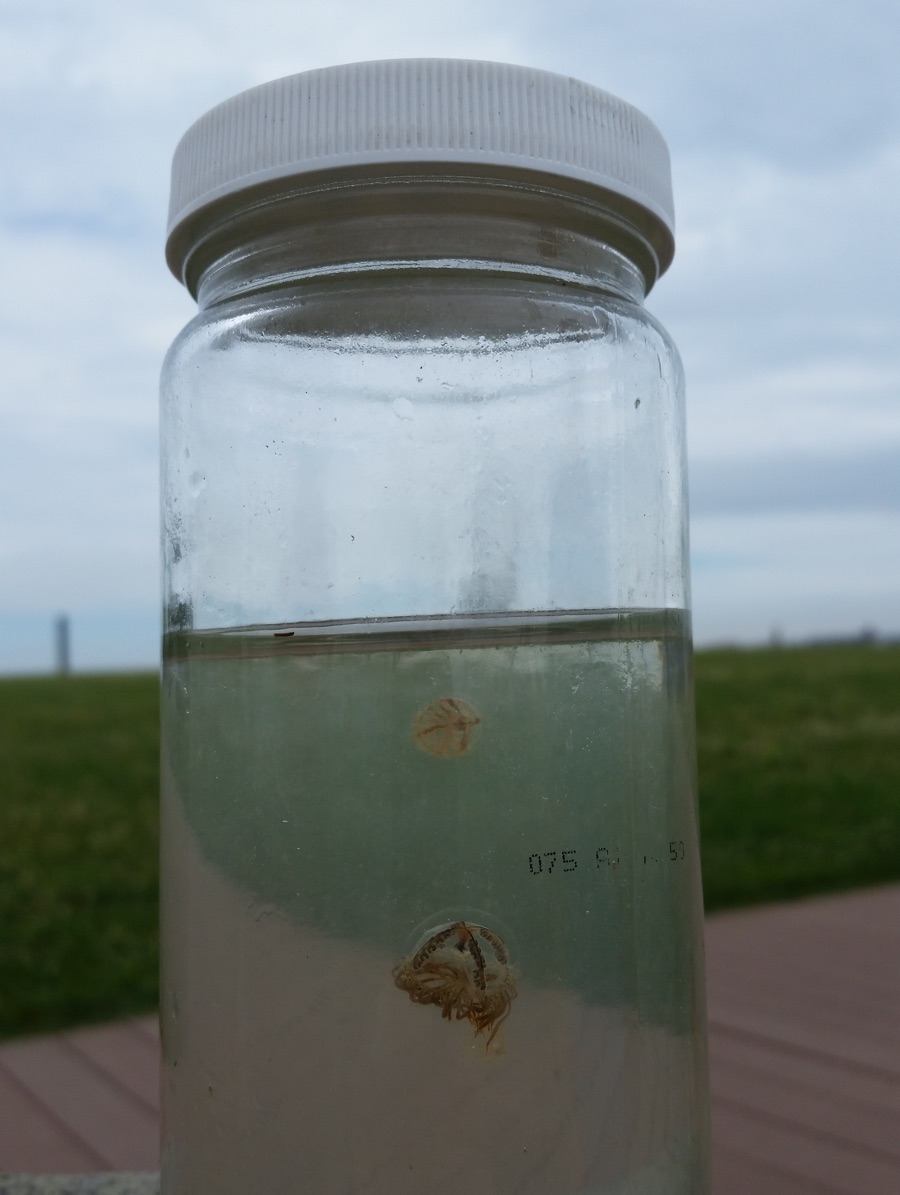

This spooky creature is a clinging jellyfish, and it turned up on Tuesday in a North Wildwood pond. Photo courtesy of Paul Bologna.

Water-waders, beware: A smack of jellyfish are slowly descending upon the Jersey Shore. Just before Memorial Day weekend, researchers found hundreds of “clinging jellyfish” — a species roughly the size of a quarter and known for its crippling stings — in Ocean County’s Barnegat Bay. On Tuesday, another 150 jellyfish were discovered in North Wildwood, some 75 miles south — and no one’s quite sure how they got there.

Although the find in North Wildwood — in a saltwater pond near the Hereford Inlet Lighthouse — represents the farthest south a clinging jellyfish has ever been found in Jersey, the species (Gonionemus vertens, officially) has made a home in the state since at least 2016. According to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, the jellies are native to the Pacific Ocean, and were first introduced to the Atlantic Ocean back in 1894, possibly from the transport of Pacific Ocean oysters. (Thanks, capitalism.) The incursion into Jersey has mostly been confined to the area of Barnegat Bay, as well as the Shrewsbury River near Long Branch. That is, until now.

Two captive clinging jellyfish. Photo courtesy of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.

This particular species of jellyfish is insidious because it packs such a punch for its small size. (Its stings aren’t life-threatening, although if you do get stung, you should apply vinegar to the wound and rinse off with saltwater.) They’re sneaky above all else: Researchers say you can hardly spot them in the water. Fortunately for beachgoers, the clinging jellyfish tends to hang just outside the ocean, preferring the calmer waters of bays and estuaries.

In short: You don’t have to worry so much about encountering one of these little guys at the beach. If you’re wading in some nearby waters, however, you’d want to keep an eye out, and the Jersey DEP recommends you wear long sleeves.

It seems a sort of cruel joke, but jellyfish presence at the Shore tends to line up almost perfectly with the summertime beach season. The creatures start appearing around the middle of May and stick around until August. Populations don’t migrate, which makes the recent find in Wildwood that much more confounding. Oftentimes, researchers say, the spread of a clinging jellyfish can caused by “accidental translocation.”

For those who want to follow this budding war of jellyfish aggression in real-time, the DEP publishes an interactive map of all confirmed sightings. Hopefully it goes without saying that if you think you’ve spotted one of these creatures, you shouldn’t touch it. Take a picture if possible, and contact Paul Bologna, a biology professor at Montclair State University tracking the jellyfish for the DEP, to let him know.