Lew Blum, the Tow-Truck King Philly Loves to Hate, Needs a Hug

He was known for hauling away illegally parked cars all over the city. Then he pissed off the wrong people.

Lew Blum at the West Philly impound garage where he might have towed your car. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Up until September 22, 2015, it was Lew Blum’s world; we just parked in it.

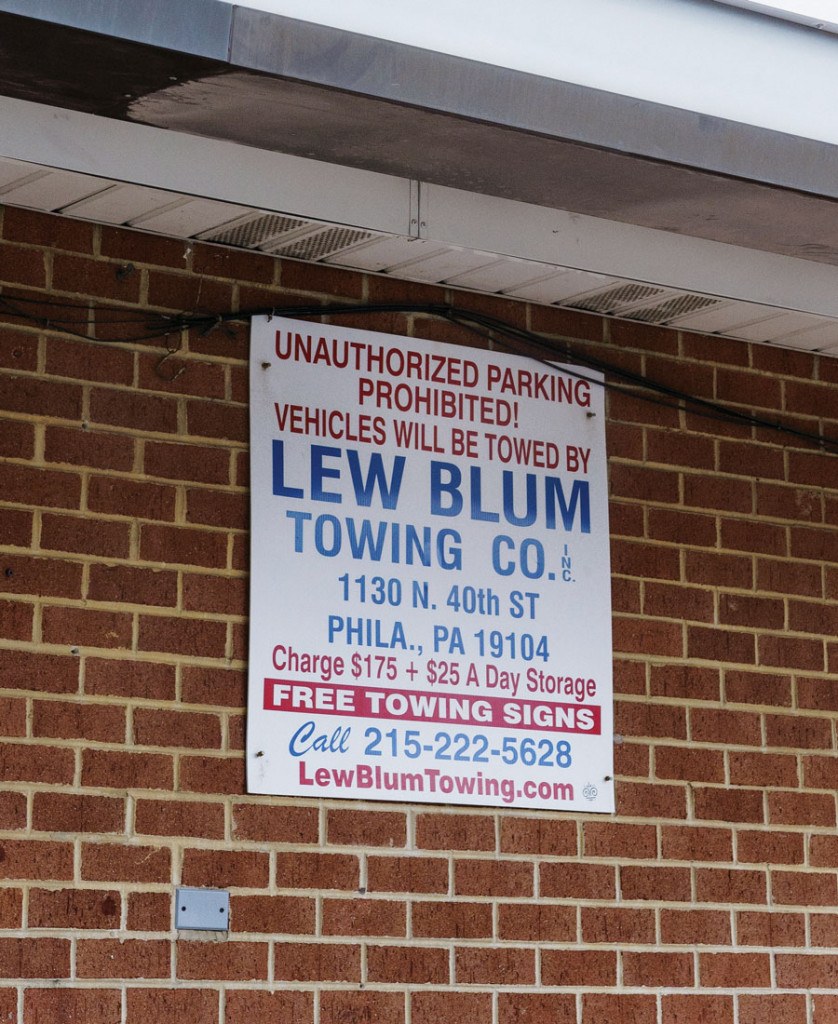

From behind the steel-reinforced walls of his fortified bunker in West Philly, Blum lorded over a vast and lucrative towing empire that specializes in removing unauthorized vehicles from private parking space across the city. His name is a household word in Philadelphia, where upwards of 10,000 LEW BLUM TOWING signs hang in ubiquity on the walls adjacent to more than 3,000 private parking lots, spaces and garage doors, warding off would-be illegal parkers the way scarecrows ward off crows. When that fails, Blum’s wreckers tow away those who ignore the warning, at the behest of irked private-parking-space owners and lessees. Nothing enrages us more than taking away something that belongs to us, especially our cars, which in America is tantamount to stealing our eternal souls. Blum was good at it, so good that he became The Most Hated Man in Philadelphia in the court of public opinion. Lew doesn’t take it personally — it’s just one of the many occupational hazards of being a tow-truck-drivin’ man. Besides, somebody’s gotta be the villain in this movie.

Raised on the dog-eared mean streets of the Bottom in the middle of the 20th century, Blum was born into a burgeoning towing dynasty. Towing was the family business going back generations. His grandfather, Lew Smith, more or less invented tow-truck enforcement of private parking in this city. Blum’s uncle was George Smith — of George Smith Towing fame — and between the two of them, they split the city in half. Sure, there were other towing companies in town — Jimmy’s, Earl’s, Empire — but they mostly nibbled around the edges of Blum’s and Smith’s respective fiefdoms. And yeah, some towers ran their businesses like pirate ships, but that wasn’t Lew Blum’s problem. He’s been saying for years that the city should be singling out and cracking down on the bad actors.

Blum says that in the past two years, his $2 million towing empire has lost 80 percent of its value. He’s exhausted his life savings just trying to keep his head above water.

In recent years, getting your car out of Blum’s impoundment lot would set you back $200, and up until 2017, his wreckers were hooking 20 cars a day. He estimates the value of his business back then in excess of $2 million. But all that began to change on or about September 22, 2015. That was when now-indicted and theretofore all-powerful union boss Johnny Doc emerged from an undisclosed location to discover that his illegally parked car was “on the hook” of a wrecker from an unnamed towing company, as spelled out on page 118 of the 109-count federal indictment of Johnny “Doc” Dougherty, business manager of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 98, and Philadelphia City Councilman Bobby Henon. After telling the tow-truck driver who he was, Johnny Doc shelled out the requisite $200 to get his car off the hook. Further insult was added to injury when the tow-truck driver was unable to make change and Doc was shorted $10. Shortly thereafter, according to the indictment, Doc called Bobby Henon to vent and plot his revenge.

It’s important to know that in addition to his $130,000 salary as a City Council member, Henon was paid $72,000 annually for a job at IBEW Local 98. It remains unclear exactly what his job duties were at IBEW — Henon and the IBEW declined to comment when asked to clarify — but from the feds’ point of view, the $72K a year was essentially the price Johnny Doc paid to have Henon enact his political will within Council chambers. “I think tomorrow, we fucking put in a bill to certify, ’cause if they can rob me, they can try to rob anybody,” Doc told Henon, according to the indictment. What they were going to do, Doc said, was put a bill through Philadelphia City Council to require tow-truck drivers to go through training. Referring to Henon’s fellow Council members, Doc told Henon, “Just tell them you’ve heard nothing but complaints [about the tow-truck companies] … just smoke ’em.” Referring to the tenner he was shorted, Doc said, “That $10 is going to cost their fucking industry a bundle.”

A week later, according to the allegations, Henon directed a staffer to “make a secret recording” of the impoundment lot of the towing company Doc had tangled with and then draft a resolution titled “Authorizing City Council’s Committee on Licenses and Inspections to hold public hearings to investigate the operations of [the name of the company that towed Dougherty’s car] in the City of Philadelphia for the purposes of protecting the general welfare and public interest of the residents of Philadelphia. … ” Fast-forward nine months: On June 16, 2016, a bill was introduced to City Council to amend Section 9-605 of the Philadelphia Code, the one called “Towing,” to add a requirement that a car parked illegally in a private parking lot or driveway first be ticketed by police before being towed. The bill was sponsored by Council member Maria Quiñones-Sánchez. A public hearing was scheduled for late November of 2016.

One of Lew Blum’s ubiquitous signs. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

When Blum heard that the ticket-to-tow bill was a foregone conclusion, his blood ran cold. He knew the business well enough — it was in his blood, after all — to see the bill for what it was: an existential threat not just to his livelihood and the livelihoods of his competitors, but to the very notion of private parking enforcement in Philadelphia. He could see how this would play out: The cops, busy with actual crime, would de-prioritize complaints from private-parking-lot owners. It would routinely take hours and multiple phone calls to 911 to get a car ticketed. Sometimes the cops wouldn’t show up until a day later; by that point, the illegal parker would have long since escaped and/or the private-parking-space owner would have given up. This would inevitably result in a precipitous drop in revenue for the towers. He knew all of this because then-Councilman Jim Kenney had pushed a nearly identical bill through Council back in 2010, only to realize once it was signed into law that while it looked good on paper, in practice it was unworkable — for all the aforementioned reasons — leading to its repeal after three years.

Blum desperately arranged meet-and-greets with Council members to try to convince them to vote against the bill. He even brought cookies from the Acme, and poured his heart out to anyone who would listen; he was practically in tears in Council member Mark Squilla’s office — but the ticket-to-tow bill continued slouching toward Mayor Kenney’s desk.

As the bill worked its way out of committee and onto the Council floor for a final vote, where passage looked all but inevitable, Blum put out a call on Facebook for his fellow tow-truck operators to show up in their trucks and circle City Hall, horns blaring, much like the Teamsters had in protest of the soda-tax vote a few months prior. Blum waited for a cavalry that never came.

Truth be told, he thought the industry had brought this on itself. Rogue towers using bait-and-switch tactics to trick drivers into parking illegally had poisoned the waters for everyone. Whereas Blum prided himself on running a fair and honest and color-blind company — he has an A rating from the Better Business Bureau — some of his competitors could be predatory and greedy and as mean as the junkyard dogs that guarded their impoundment lots. He still remembers the night in August 2016 — just three months prior to City Council’s scheduled hearing on ticket-to-tow — when Fox 29 showed footage of wreckers from George Smith Towing removing cars from South Broad Street after apparently hiding the NO PARKING sign required by law. Blum immediately called one of his contacts at the company, which had been sold out of the family 15 years earlier, and pleaded with him to refund all the towees’ money and give them back their cars. The optics were terrible, Blum said; this would give the entire industry a black eye. “Fuck ’em,” the guy from George Smith said, according to Blum. “That’s $1,600!” (When I reached out to George Smith Towing to get their side of the story, whoever answered the phone hung up when I identified myself as a reporter.)

On December 8, 2016, Council voted 15-1 to pass Bill 160682 (with Councilman Oh casting the lone nay). On January 24, 2017, Mayor Kenney signed it into law. The impact on Blum’s bottom line was calamitous. He says that in the past two years, his $2 million towing empire — the product of 41 years of sweat equity — has lost 80 percent of its value. Blum went from towing an average of 20 cars a day — at $200 a tow, his take averaged $4,000 daily, or $1.5 million annually — to just two cars a day. That adds up to $146,000 annually. In the two and a half years since the towing bill passed, Blum, nearing retirement age, claims, he’s exhausted his life savings just trying to keep his head above water. His competitors have fared even worse. In the wake of ticket-to-tow, two of the major tow operators in the city — Roxborough and Siani’s — have liquidated their businesses or sold them off.

Making Lew Blum appear in the flesh is no easy task. Despite his Mephistophelian public image and how ALL CAPS megaphonic he is on social media, he’s actually a very quiet, private person. He conducts his business remotely from the secure, undisclosed location he calls home, handling the phones, talking angry lot owners down off the ledge, dispensing wreckers to hook scofflaws and shit-posting City Council on Facebook and Twitter, like, hourly. The first four or five conversations I had with Blum were over the phone, with him repeatedly begging off my entreaties to meet in person, saying he was too busy. Finally, he agreed to get together at the Oregon Diner in South Philly.

I first met Blum back in 2002, when I wrote about him for the Philadelphia Weekly in a profile bluntly titled “Who the Hell Is Lew Blum?” My memory of what he looks like is vague: trim, well-groomed and ruggedly handsome, like that B-movie character actor your dad liked who always played tough guys in the ’60s. I scan the diner but don’t see him anywhere and settle into a booth in the back to wait for him. When he does appear, it’s magical in a Goodfellas kind of way:

A waitress ambles up to my table and asks, “Are you Jon from Philadelphia magazine?”

Yes, why? I ask.

She just looks at me, saying nothing — not even a “hon” or a “toots” — before walking off. When she gets three booths away, she nods as she passes, and the man sitting there with his back to me stands up and pivots around and points his finger at me, flashing a 100-watt grin and giving me that “You old son of a gun!” look. He asks if we can switch sides of the table so he can have his back to the wall and face the door.

Niceties out of the way and seating chart sorted, talk soon turns to his origin story. Lew Blum was born in 1955, and for reasons he won’t go into, he was raised by his maternal grandparents — Fannie and Lew — in a big house at 52 North 38th Street, in the middle of the Bottom. During the Depression, his grandparents bootstrapped their way from below the poverty line up to relative prosperity by turning other people’s trash into money King Midas-style, harvesting old tires and gluing together the good parts to make new ones. “They were hustlers,” says Blum. “They’d take five dead car batteries, strip out the good parts, reassemble them, charge them up, and sell them for a quarter apiece.” By the tail end of the ’30s, Lew Smith, Blum’s grandfather and namesake, had saved enough to buy a garage at 38th and Powelton and started an auto repair business. When a tow-truck operator wanted to charge the confiscatory price of six whole dollars to move a disabled car, Smith decided to cut out the middle man and got himself a wrecker. When he discovered there was more demand for towing services than auto repairs, he adjusted his business plan accordingly, and Lew Smith Towing was born. “People were always calling my grandpop and saying they had someone blocking their driveway or parking lot,” says Blum. “So we’d put a tow sign on your property, you’d sign a contract, and we’d tow the cars.” Lew Smith was a bartering man. If towees couldn’t pay in cash, they’d pay in bottles of milk or loaves of bread or chickens: “My grandfather always said, ‘A favor owed is worth more than the dollar,’ and I still run my business that way.”

Everyone worked in the family business — all six of Lew’s uncles and all three of his aunts as well as his mother and her mother. It was somewhere around the sixth grade when Lew stopped going to school so he could hang full-time at the garage. “I hated school,” says Blum. “All I wanted to do was work in the garage with my grandpop.” So his grandfather paid the truant officer to look the other way. When Lew was 17, his grandfather passed away. The business was passed on to his Uncle George, and the name of the family business changed to George Smith Towing.

In 1978, when he was 23, Blum was ready to strike out on his own. He’d saved up $500 and made a down payment on his first tow truck. Every week for 15 weeks, he paid the man $100 until the truck was his. It wasn’t much to look at, but it dragged cars where he needed them to go. Blum worked 18-to-20-hour days for $4 a tow. By the following year, he had rented his own lot, at 3825 Pearl Street. He parked an old yellow school bus in the lot, ripped out the seats, and made it his office. He ran a telephone line to the bus. He had a Johnny-on-the-Spot installed in lieu of a proper bathroom. From the get-go, he understood the power of advertising. He had stickers made up that said LEW BLUM TOWING, along with his phone number. He would start at Front and Walnut and tag every phone booth from there to 63rd Street. Then he’d head back down Chestnut and do it all over again. “Wherever people were,” he says, “I would go — to restaurants, bars, wherever they had pay phones. Stick them with stickers: Lew Blum, Lew Blum, Lew Blum.”

In an attempt to map a through line — or the lack of one — from Johnny Doc’s 2015 fuck-the-tow-trucks edict to Henon to Council chambers to Mayor Kenney signing Bill 160682 into law a year and a half later, I reach out to Dougherty and members of City Council. Henon and Johnny Doc decline to talk, issuing the following statement via their shared spokesperson, Frank Keel: “It’s our policy not to address any questions directly or indirectly related to the federal indictment.” Both Councilman Squilla and Councilwoman Quiñones-Sánchez deny any connection between the ticket-to-tow bill and the Johnny Doc/Henon plot intercepted by FBI wiretaps.

“Never happened,” says Squilla. “I know what’s written in the paper, and people believe it. This was started by Councilwoman Sánchez, and she was motivated by stories from her constituents complaining about some of the antics of towing companies in her district.”

Quiñones-Sánchez agrees. “The ticket-to-tow policy originated in 2010 with then-Councilman Jim Kenney and was reversed in 2012 at Mayor Nutter’s request,” she says. “In 2016, I authored legislation to reinstate it in response to vehement constituent outcry related to predatory and illegal towing practices, widely documented in the media and in testimony at Council hearings.”

Let the record show that in 2015, Johnny Doc used IBEW funds to primary Quiñones-Sánchez, and, she says, he’s doing it again this year. So why would she go after the private towing industry on his behalf? Beginning to wonder if I’m chasing the wrong stick, I reach out to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, which authored the Johnny Doc/Bobby Henon indictment. I ask acting spokesperson Michele Mucellin why the Doc and Henon let’s-screw-the-tow-truckers intercept was included; after all, it’s not a crime to consult constituents when crafting legislation. Citing an ongoing investigation, she declines to address the matter directly other than to say that everything in the indictment is there for a reason.

One day, Lew Blum calls and says he wants me to ride along with Ray, his best tow-truck driver, to get a taste of what it’s like out there. This sounds like a capital idea to me — I’m picturing a scene out of Repo Man where we’re driving around all day snorting bathtub speed and blasting Black Flag while looking for aliens and rogue cars. Sadly, none of those things come to pass.

Bright and early one morning in late February, I show up at Lew Blum Towing HQ on North 40th in West Philly. When you walk in the front door to get your car back, you enter a dungeon-esque anteroom where the floor, walls and ceiling are all covered in reinforced steel diamond-plate. There’s a bulletproof service window that’s entirely blacked out except for a mail-slot-shaped peephole. It’s like walking into a secret society, or a snuff film. These structural impediments to direct human contact between the towee and the tower are intended to protect Blum’s employees from harm. Turns out, right or wrong — and nobody ever admits to being wrong — people get really, really mad when you take their cars and make them pay you $200 to get them back. There are often threats of violence, curses and imprecations. One time, a woman registered her extreme displeasure by urinating in the corner. Another time, an elderly man beat his cane to splinters swinging it like a baseball bat over and over against the blackened service window.

The anteroom. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Two disembodied eyes appear in the peephole and want to know what I want. When I explain that I’m here to ride with Ray, the eyes tell me to wait a sec while he locks up two bluenose pit bulls, Marco and Princess. The door opens, and a young, dreadlocked man beckons me in. His name is Julian. He’s 27. He’s lived his whole life in West Philly. Before he started working for Lew Blum, he worked at the airport. “Believe me, this is 10 times better than working at the airport,” he says. The office is spartan in extremis, just the dingy light of a naked lightbulb illuminating an old chair crushed into submission by the dungaree-muffled thud of a million asses taking a load off and a matching desk that also looks ready to give up. Julian’s been monitoring the impending arrival of Bryce Harper. “He’s the LeBron James of baseball — no question about it,” Julian says, standing up and offering me the only chair in the room while we wait for Ray to show up for his shift.

Ray Sierra is, I think we can all agree, a perfect name for a Tow-Truck-Drivin’ Man. Ray is a sweet-natured, 50-something half Italian/half Puerto Rican guy who started out in retail before transitioning into towing when his knees started to go. He lives in Levittown — “Takes me an hour each way with traffic” he says — with his wife. Somehow, they’re putting two sons through Kutztown on a tow-truck-drivin’ man’s salary. Ray’s father was a Philly cop turned bounty hunter. Every week or so, a man would show up at the front door and drop off a yellow envelope filled with mugshots of bail-jumpers, and Dad would disappear for a few days or a few weeks. If you squint, you can almost see the Venn diagram where towing illegal parkers intersects with hunting fugitives from the law.

Lew Blum employee Earl Brunson with Marco and Princess. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Ordinarily, Ray doesn’t go out until there’s a call from a lot owner to tow an illegal parker. When no calls materialize, we pile into a shiny cherry-red Ford 450 wrecker, load up on coffee at the nearest Dunkin’, and go looking for trouble. “At any given point in time, 80 percent of the cars in private lots are illegally parked,” Ray assures me. “It’s invisible to most people, but I drive around all day, I can see it.

“You see, nobody is afraid of getting towed because they know the cops don’t show up for hours, if at all,” he continues.

For the next four hours, we drive around looking for action. We hit a couple Rite Aids, the lot at Wing Phat off Washington, and the lot next to Aircon Filter near Edgar Allan Poe’s house — and alas, there’s no action to be found. To pass the time, I ask Ray to tell me some Tow-Truck-Drivin’ Man war stories. He doesn’t disappoint.

“We run into some hairy situations. People think that parking-lot enforcement is just a regular tow job,” he tells me. “We put our lives on the line. We run into some hairy situations. I mean hairy.”

He’s not kidding. One time, he cut a guy parked illegally in a Wells Fargo lot a break and lowered his car off the hook; the guy followed him for seven blocks before pulling up next to him near the Home Depot on Roosevelt, rolling down his window, pointing a 40mm at him, and pulling the trigger twice. Ray says one bullet went through the passenger-side door, through the seats, and nearly out the driver-side door, narrowly missing his legs. The second shot whizzed past the back of his head.

A couple months ago, at a different bank parking lot, a guy snuck up behind Ray, pulled his hood over his head, and put him in a headlock, all the while working the lever to lower his car. Ray throat-punched him, and they wrestled for a while until the cops showed up.

Ray Sierra at Blum HQ in West Philly. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Then there was the time two summers ago that he was towing a black Toyota Camry “with very tinted windows” from a lot in the projects around 13th and Girard. “Five young men walk up to me — very young, like 15 to 18,” says Ray. “All five pull up their shirts to show me the 9mm [pistols] tucked into their waistband. They were like, ‘Let it go.’ I’m shaking my head: not gonna happen. And then two of them pull out their guns and smack back the chamber: ‘Don’t make us ask you again.’ We just stared at each other, and finally I just decided it wasn’t worth it.”

Plus, his wife would have killed him if he got shot. Unlike Harry Dean Stanton in Repo Man, Ray doesn’t pack heat. “It would just escalate the situation,” he says. “Safety is priority one. If there’s two guns, one of them is going to go off sooner or later.”

Want to know a secret? In the wake of ticket-to-tow, there’s functionally no such thing as private property in Philadelphia anymore, at least when it comes to private parking lots, spaces and driveways. With the exception of street parking and public spaces patrolled by the PPA, you can park wherever you like these days, at least for an hour or two, with little fear of consequences. I speak with nearly a dozen tow-truck operators and private-parking-lot owners, and they all echo Blum’s beef.

“Most of the time, the police don’t come. When they do, it takes at least an hour for them to show up,” says Mikina Harrison, owner of A Bob’s Towing. “And then they might make an executive decision not to ticket. I’d say on about two out of 10 calls, we are able to successfully tow an illegally parked car. The only reason we are still in business is because we do other things: auto repair, breakdown towing, etc.”

The Philadelphia Police Department declined an opportunity to provide evidence disproving these allegations.

Nobody will deny that prior to passage of the law, there were rogue tow-truck operators in this town who were employing dishonest and predatory tactics to rip off the public. And while it’s true that ticket-to-tow treats that kind of cancer, it kills the patient in the process. What tow operators and private parkers are asking for is revised legislation that takes a more surgical approach to the problem, so it cuts out the malignancy without nuking the entire industry. There are some folks who wonder if the collateral damage caused by ticket-to-tow is actually a hidden function of the law, not a flaw — that it’s a back-door way to crush the private tow operators and hand private parking enforcement over to the Philadelphia Parking Authority.

I ask Councilman Al Taubenberger, who voted “Yes” on ticket-to-tow and also happens to sit on the board of directors of the PPA, if there’s any truth to that talk. Through his spokesperson, Frank Keel (yep, the same mouthpiece as Johnny Doc and Bobby Henon), he issues the following statement: “Councilman Taubenberger sees no need to amend or end the law. As to the whisper campaign of the law being nothing but a PPA-orchestrated attempt to take over private parking in the city, it’s utter nonsense, a baseless rumor.” Watch this space.

By the spring of 2018, Blum was really feeling the hurt that ticket-to-tow put on his bottom line. The phones stopped ringing; revenue dried up; he had to lay off five employees and dip into his personal savings to keep the lights on. Having worked through the seven stages of grief — from shock to denial to anger to bargaining, etc. — Blum arrived at the rarely discussed eighth stage: revenge. If he couldn’t beat City Council, he decided, he would join them. He began floating the idea of running for one of the at-large City Council seats in the 2019 May primary, with the following campaign slogan: “You Took My Job, Now I’m Taking Yours!” And sure, he was getting into this to repeal the ticket-to-tow law, but he wouldn’t be a single-issue candidate. He has a lot of ideas about how to improve life in Philadelphia.

First, he would spend $20 million a year staffing up on beat cops. “I want to make Philadelphia a 12,000-man force,” he says. “I want boots on the ground. Everyone deserves to live on a safe street.” The Police Department says there are currently 6,300 cops; Blum says that’s not enough. “Take that number and divide it by three shifts,” he says. “Take half and put them behind desks. Take the other half and make them detectives. Now, how many people do you have patrolling the streets of Philadelphia? Not enough!”

To alleviate the cruelties of mass incarceration while simultaneously beautifying the city’s trash-strewn streets, Blum would replace prison with community service for non-violent first-time offenders — vandals, car thieves, pot smokers — and put them to work cleaning up city streets. “It’s costing the city $175 to $225 a day to keep a person in prison,” he says. “Which adds up to $90,000 a day for the care and feeding of 500 inmates.” Blum says he’d take those 500 people out, put them on home release, and have them clean the streets for $10 an hour. Five hundred people earning $10 an hour, working eight-hour shifts, will cost $40,000 a day. “I just saved you $50,000 a day and gave you clean streets!”

And he’s just getting started.

He would put seat belts on every school-bus seat in the city. And he’d double teacher salaries. “Somebody had said that we need to do more for our kids to help them find jobs,” he says. “To do that, we have to educate them better. I want to take $100 million right from the PPA and give it to the school board. I want to give the teachers a raise. Teachers in Philadelphia are making $40,000 a year. They need to be making $80,000 a year!”

You have to admit: These aren’t terrible ideas. Quite the contrary, in fact. But Councilman Blum? A moon shot, to be sure. Still, given his rough-hewn charisma, gritty humor, tough-guy-who-helps-people persona and capacity to dispense blunt working-class wisdom with a folksy — albeit often grammar-challenged — charm, not to mention the restiveness and unpredictability of a city electorate enraged by the soda tax and skyrocketing property taxes, plus the fact that there are 55(!) candidates for City Council on the ballot for the May 21st primary, anything could happen. Especially if 2019 turns out to be a Throw the Bums Out year. And given that there are surely more shoes to drop in the feds’ investigation of Bobby Henon and Johnny Doc and the shadowy workings of the City Hall/Local 98/PPA Industrial Complex, we could be looking at a seismic scrambling of the chess board of Philadelphia politics. And then all of Johnny Doc’s horses and all of Johnny Doc’s men won’t be able to put the electoral calculus of the “corrupt and contented” status quo back together again.

That was the fairy-tale ending to this story — and we all lived happily ever after — but this isn’t a fairy tale. Cut the trumpets; there will be no two-fisted victory dance atop the Art Museum steps for Lew Blum. Rocky Balboa doesn’t go to City Hall and throw the bums out. Not this time, anyway. “I’m not running,” he says after a long, deflating sigh, shoulders slumped, eyes downcast. “Every campaign manager I talked to wants to know if I have money. ‘No, it’s all gone. All of it.’ A million dollars, two million, maybe.”

Plus, there’s the residency issue. Turns out Blum lives outside the city limits. (He asked that we not reveal the exact location because “a lot of people hate Lew Blum.”) He was going to establish residency, but when push came to shove, he says, he couldn’t come up with the first and last month’s rent on a tentpole to hang his shingle on. “This city has taken my livelihood,” he says. “I put it out there now about Sánchez. You’ve deprived me of my Christmases. You’ve deprived me of my birthdays. And what I mean by that … I can’t do for my babies like I used to. We can’t have fun like we used to. We can’t go places like we used to, because I don’t have the money! It’s very depressing. My credit score is probably below 500 again now because of this. I’m behind on bills because of this. I haven’t had a payday since February 2017. If I don’t go to the gym, I’ll just be at home. Depressed. Very depressed.”

Admittedly, Blum may not be the most effective advocate for his cause. Councilman Oh finally had to block him on Twitter after being carpet-bombed with hourly demands that he repeal Bill 160682, despite the fact that Oh voted against it. Some members of City Council think Lew’s crying wolf, but here’s why I believe him. Lew Blum is an old-school self-made man — built himself up from nothing and proud of it. Goddamn proud. And rightly so. Plus, he keeps to himself; he doesn’t put his business out on street. He’d rather chew broken glass than drive to a diner to tell a relative stranger who’s going to tell everyone else in Philadelphia that one year shy of retirement age, Lew Blum is flat fuckin’ broke.

But he’s desperate.

And that’s another thing: He’s sick of being called The Most Hated Man in Philadelphia. “I’m not a bad guy, I have a heart,” he says. “Nobody sees all the times I cut people a break. One time, there was a Little League team that came to pick up a vehicle. The coach was there, and there were three little boys looking at me with these big brown eyes. I’m like, ‘Look. Here’s your money. Treat them to pizza.’ Nobody writes about that. I’ve had grown men cry. ‘Take your keys. Get out of here’ — I never even got a thank-you. My family gets upset with me when I cut a break to City Council.” (Council members lobby him to let their constituents off the hook.) “‘Why do you do that? They do nothing for you. Nothing. And the constituent you helped is not going to praise you! They’re going to praise the Council-person.’ And I’m like ‘No, the favor is worth more than the dollar.’ Well, that backfired on me.

“I was just happy doing my job,” he says finally. “Americans have a birthright to pursue our happiness! And as long as we do it right, we should be allowed to do our job.”

The hazy winter sun is setting on the Oregon Diner, leaving behind a grimly darkening twilight as the lunch shift gives way to the dinner shift. The waitresses switch out the ketchup bottles with fresh soldiers, signaling the inevitable changing of the guard. As Lew and I part ways in the parking lot, there’s a sudden squall of snowflakes fluttering atop the grime. He pulls up the collar on his black windbreaker — an overly optimistic sartorial choice for a late February day. “Hey, did you hear about the guy from Jersey that won $273 million in the lottery?” he says. He looks over his shoulder at a shabby newsstand on the sidewalk where the locals are lining up to buy Powerball tickets. He turns back to face me as we shake hands, and I can’t quite tell if the look in his eyes is determination or defeat. “You know what,” he says. “I think I’m gonna go buy a lottery ticket.”

Published as “The Tow-Truck King Needs a Hug” in the May 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.