A Philly Photographer on His Decade of Documenting the Opioid Epidemic

Jeffrey Stockbridge’s work turns again and again to Kensington, a neighborhood in the grips of a crisis that he says is “all too often reduced to a photo of a needle.”

Jeffrey Stockbridge’s exhibit at Drexel University runs until March 30th. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Jeffrey Stockbridge did not come to photograph the opioid epidemic in Philadelphia by seeking it out. He spent his time, as a photography student at Drexel in 2005, roaming the city in search of abandoned buildings. He took their portraits — depicting their creaks and cracks in a way that made them almost seem human. Stockbridge’s eye remained fixed on those old ghosts for years, until he began to realize his buildings weren’t so abandoned after all.

People tended to gather around the structures he photographed. So Stockbridge spoke with them, learning that many were addicted to drugs. “I ultimately became more interested in the people I was meeting than the spaces I was photographing,” he says. “So I started to photograph the people.”

He soon ended up in Kensington. At the time Stockbridge began photographing there, in 2008, opioids were killing around 250 people in Philadelphia every year. A decade later, that has figure soared to more than 1,000. Stockbridge’s work in Kensington culminated with Kensington Blues, a self-published book of photos and interviews documenting growth of the crisis — and the people living it.

On Monday, I spoke with Stockbridge by phone to discuss the Kensington Blues project, which also lends its name to an exhibition of his photos on display at Drexel’s Paul Peck Alumni Center through March 30th. (Stockbridge will be moderating a panel — which includes former Governor Ed Rendell and Silvana Mazzella of Prevention Point — about the opioid epidemic on Wednesday evening at the university.) Our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity, touched on media coverage of the opioid epidemic — including Stockbridge’s own — and the ethics of photographing people mired in addiction.

Do you consider yourself an artist or journalist when it comes to taking these photographs of the opioid epidemic?

The original Kensington Blues photographs were more of a personal art project. Then, last year, I shot a story for the New York Times magazine, which is journalism. So I’ve been crossing back and forth between that line for some time.

How does your approach change from one to the other?

My approach when I’m doing journalism is to observe and report. You do have to gain people’s trust in order to make their photographs, but you’re keeping a certain distance and trying to exercise objectivity — photographing everything as you see it unfold before you. Whereas with Kensington Blues, there were a lot of things I didn’t photograph.

A young woman sleeps in a tent during the day beneath the Kensington Avenue underpass. After homeless drug users were evicted from the abandoned tracks, many relocated to four tunnels in the neighborhood. Photo and caption courtesy of Jeffrey Stockbridge.

In some of your shots, you’ve photographed people sleeping. How do you navigate permission, or lack thereof, in either case, artistic or journalistic?

It’s a question that I ask myself after I’ve made the picture: What does this picture communicate? Does this picture deserve to go out into the world? When you’re making that photograph, you have to approach that subject with a certain amount of sensitivity. I don’t want to really photograph people if they don’t want to be photographed. In the case of someone who’s sleeping in a tent, they’re not really in a position to be able to give consent. But they’re also not in a position to be able to deny it because they’re out on the street. And it’s within my rights as a photographer to photograph someone on the street.

The challenge obviously is rights versus ethics. That’s something that comes up a lot in this domain, right? How do you make that decision yourself?

I’m not trying to just show people at their worst. There’s a lot of photographs that I didn’t make, where I saw things that were rather horrific. You’re speaking specifically about this one picture where this woman is sleeping in a tent, and for that picture, I thought it was just such a gentle photograph — the space that this woman is curled up into this little ball, inside this tent on the edge of a dark tunnel. This is a picture of someone you might not expect to be in that scenario, to be stuck in that situation. I think it was powerful and it deserved to be captured as a photograph.

How do you feel the media has covered the opioid crisis specifically in Philadelphia?

Like they’d cover it anywhere: They cover it like it’s a war zone. I struggle with whether or not that’s the kind of work that I like, or even the kind of work that I want to make. I don’t know. I tend to not want to look at a lot of that type of work. But I can’t say that it doesn’t serve a purpose and that it’s not journalism.

A lot of dialogue has to do with the fact that, to many people, the coverage has been sensationalized — especially when the national media parachutes in looking for the worst thing and then proceeds to leave once they’ve gotten it.

I hear you. But when something is as bad as it is in Kensington, it needs to be acknowledged. It’s necessary to show those extremes.

There was some criticism of the New York Times magazine piece, including your photographs depicting the faces of people engaged in illegal drug use. And there’s a school of thought that that’s not an ideal way of portrayal. What do you think?

My thoughts about that are pretty simple and straightforward. And that is: If it’s happening out in the open, where a kid can see it when he’s walking home from school, then I have every right to photograph it. I think it serves a purpose. I mean, it’s insane what was happening out in the open. And a lot of Philadelphians, they don’t even go up to Kensington. They ignore it.

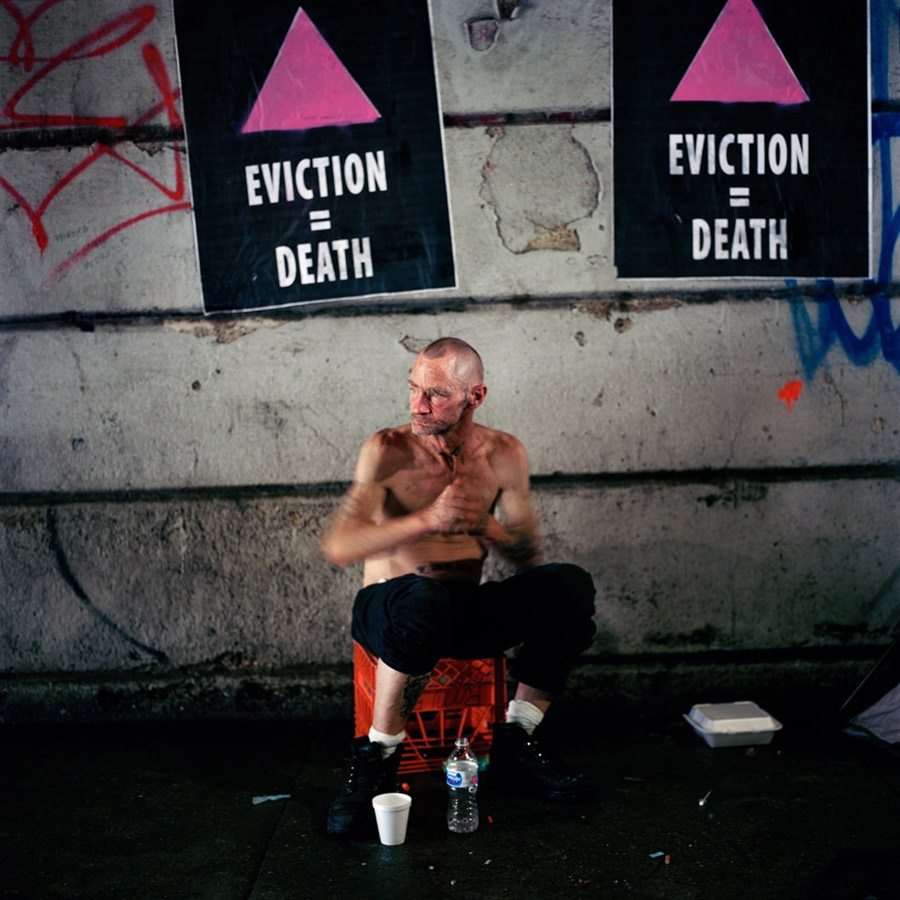

Country rocks back and forth after injecting heroin the day before the city evicted drug users camped beneath the Kensington Avenue underpass. Photo and caption courtesy of Jeffrey Stockbridge.

So I assume it’s fair to say that you fully stand by all of the photos that ran in that piece.

Absolutely. I do. And to point this out as well, I shot 100 rolls of film for this project. So you’re looking at eight pictures online, and four in the magazine. But I shot 100 rolls of film. So that’s 12 shots per roll. You’re talking over 1,000 pictures.

I assume there were also photographs that you didn’t take — well, let me ask you: When it comes to journalism, does it factor in as you said before, that you don’t want to show people at their worst? What if you’re doing something for the Times?

It makes me push my own boundaries a little bit, for sure. It makes me work really hard to try to capture as much as I can. So yeah, I think I might overstep a boundary. But then I will step back and realize, What does this photo communicate in the end? What purpose does it serve? That’s what I always ask myself. But there are things – it doesn’t matter who’s paying me to go do a shoot — that I probably wouldn’t photograph. There are things that I would say, “Hey, that’s too far.”

Has there been a photograph that you’ve sent out into the world, either journalistically or through one of your projects, that now you look back on thinking, “Maybe I overstepped that line.”?

No. That’s a simple answer.