Media-Shy Amy Gutmann Helped Produce Report Calling for Media Transparency

Former student journalists at Penn say the school’s president limited access to reporters. Gutmann’s spokesperson didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Photo by Matt Rourke/AP.

Penn president Amy Gutmann is a political scientist by trade. Like most political scientists, she believes that a free press is critical to the health of democracies.

Over the past few years, as the press has come under increased pressure and scrutiny, Gutmann has fashioned herself as something of a public intellectual on the subject of the media. Most recently, she was one of 27 thinkers to help produce a 200-page report, sponsored by the Knight Foundation and the Aspen Institute, about the ongoing crisis in journalism. The paper offered many prescriptions, including one that the media must begin to practice “radical transparency” about its sources and how it decides what stories to cover.

The irony: Gutmann herself has often been far from transparent in her dealings with the media, especially with respect to student journalists at her own school.

Penn’s student newspaper, the Daily Pennsylvanian, is financially and editorially independent of the university. That affords the publication a certain degree of freedom: Its coverage is often critical of the administration — particularly, in recent years, on the subject of student suicides.

Dan Spinelli, who graduated in 2018 and was the former executive editor of the paper, says Gutmann used to meet once every semester, for an hour, with some 20 or 30 members of the DP’s editorial staff. These meetings were casual — kind of like a get-to-know-you session with the paper’s rotating leadership — and not especially contentious. Gutmann would speak for a while, then the assembled staff would ask questions. But around 2015, according to multiple former senior editors at the paper, Gutmann had gotten into the habit of spending most of these meetings reading from what were essentially prepared press releases about the state of affairs at Penn. (I went to Penn and worked at the DP for a time, though I never attended one of these meetings.)

The staff collectively decided that at the next meet-and-greet, it would press to ask more questions in an attempt to break what Spinelli calls Gutmann’s “filibuster.” The meeting didn’t go well, Spinelli recalls: “Some of the reporters were gruff with their questions.”

That was the final hourlong meeting. Gutmann and the administration cut the time in half, and stipulated that only two or three of the paper’s top staff should attend future meetings.

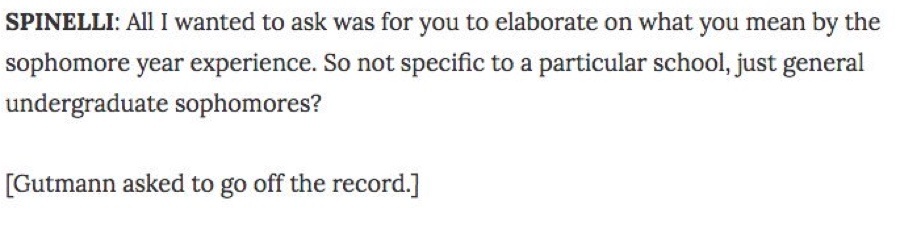

By 2017, when Spinelli ascended to the executive editor perch, he was one of the few staff members to attend the reduced and shortened gathering. In one of those conversations, held in March of that year, Gutmann asked to go off the record five separate times, often in response to seemingly trivial questions. Precocious editor that Spinelli was — practicing the precise kind of radical transparency for which Gutmann would later advocate — he published the full transcript.

An example of a Gutmann request to go off the record.

That’s the danger of radical transparency. If you’re the one being interviewed, well, you run the risk of looking silly.

The issue of media transparency extends beyond Gutmann’s own personal interactions with the press; as an institution, Penn has had a tendency to deflect media attention. This behavior revealed itself, most notably, when Donald Trump, a Penn alumnus, declared his run for president. Spinelli wrote an entire piece for Politico about the administration’s reticence to talk about then-candidate Trump. When the Atlantic wrote a similar piece last year, a university spokesperson declined comment, saying, “We just don’t comment on individual politicians.”

Penn also found itself in the middle of a less-than-positive news cycle a few years before Trump, following a series of student suicides — more than 10 in the last six years — at the school. When Huffington Post wrote a piece about one student’s death, the school apparently declined repeated requests for comment. And when Billy Penn reported on the suicides in 2015, the head of Penn’s counseling services department didn’t comment, either.

Nobody really questions Gutmann’s belief in a free press. She’s spent decades of her career researching “deliberative democracy” — the concept that a healthy democratic system must foster debate and discussion at all levels of society. The media plays the critical role of conduit in this equation, transmitting trustworthy information to the body politic.

But to recent grad Caroline Simon, another former news editor who watched this devolution unfold at Penn, it’s hard to square Gutmann’s national persona of media defender — speaking at a New York Times panel on the subject, for instance — with her treatment of the student press. “It would be like if a member of Congress was totally cool with talking to the New York Times and CNN but wouldn’t talk to his local paper, and then called himself great with the media,” says Simon.

Spinelli, who now works at Mother Jones, also mentions Gutmann’s scholarly record in her defense — and gives her the benefit of the doubt even regarding that peculiar off-the-record, on-the-record interview with her. “That struck me not necessarily as her trying to be evasive, but her being so poorly coached when it came to navigating media,” he says. “I don’t think she’s confident in her ability to navigate adversarial interviews.” The main conclusion Spinelli’s made through years of reporting on Penn is that the university — at an institutional level, above all — has a “lack of respect for the mission of student journalism.”

You might be wondering: What does Gutmann herself have to say about all this?

Well, a request for comment was sent Monday afternoon to Penn’s director of media relations. It wasn’t returned.