Teenagers Are More Stressed Than Ever. Who’s to Blame?

In Philly, well-off adolescents are experiencing a level of anxiety that’s unprecedented. What’s changed? The way we parent.

Teenage anxiety is affecting kids. Who’s to blame? Photo illustration by Michael Houtz.

One morning last fall, I was sitting at Green Engine Coffee in Haverford when I felt my phone buzz in my pocket. One buzz at first. Then another. Then three quick ones right in a row: Buzz. Buzz. Buzz. I lifted my hands off my laptop, reached into my pocket, pulled out my phone, and looked down at my screen.

“Hi. I failed the SAT.”

It was a text, sent to my wife and me by our 16-year-old daughter Sarah, whom I’d just dropped off at school 30 minutes earlier. On the way, Sarah and I had discussed the fact that today was the day she’d learn what she got on the SATs, which she’d taken in October. This made me a little nervous — not because I doubted Sarah’s abilities, but because I’ve seen, a time or two, how Sarah can react if she doesn’t do as well as she hoped to on an important test.

I continued looking at my screen. The next text came from my wife: “Wait, what?” Kate wrote.

Sarah shared her score, which, she noted, “is 100 points lower than I got on like any practice test.”

Then came the gut punch: “I’m gonna off myself.”

A word here about Sarah. I am, of course, biased, but in my estimation, she is, like her older sister, a pretty remarkable kid. Sarah is bright, spirited, good-hearted, socially aware, fast-talking, funny in a deeply ironic way. She’s thin, with long limbs, and, as she herself notes, a little high-strung, especially when it comes to school. A handful of times over the years, I’ve seen her struggle when something school-related didn’t go her way. These episodes were disconcerting in the moment, but the storms passed quickly, and I generally chalked them up to adolescence.

But now, looking at the text, weighing the circumstances, I suddenly felt deeply concerned. Was the “off myself” comment just the normal sort of drama you get from a teenager? Was it ironic, in the way some of us exclaim, “Oh, just shoot me in the head”?

Or was this a real plea, a real threat?

I got up and walked outside the coffee shop. My wife sent another text: “Sarah, please don’t talk that way you can take it several times again.”

“Mom I don’t think you understand how awful that is,” Sarah texted back. “I can’t go to any of the colleges I want to with that score.”

For some reason, at that moment, another text didn’t seem like enough, so I hit the phone icon on my screen and called Sarah. The line rang several times before she picked up. I don’t recall exactly what either of us said, though I remember she was very upset and I was trying my best to calm her down. I don’t think I succeeded very well, but by the end of the conversation, I’d at least reassured myself that nothing catastrophic was about to happen.

A bit later, I called Kate, who told me she, too, had talked to Sarah. Sarah had asked Kate to come and pick her up at school, but Kate said no, she thought it was best if Sarah stayed there and got through the day. I told her I agreed. We could figure out what to do when we all got home that night.

I walked back into Green Engine and sat down again. The score Sarah got? It might have been 100 points lower than she’d notched on her practice tests, but it was better than 95 percent of the kids who’d taken the test (not to mention 100 points higher than I’d gotten on the SAT when I was in high school). Which made me wonder: What world are we living in?

If you’re the parent of a teenager these days, the above episode might not seem too foreign to you. In so many places I go, when the talk turns to kids, the theme ends up being the same: how stressed they are; how overscheduled and overwhelmed they feel; how much pressure they’re under to achieve and succeed.

“We hear it one or two nights per week,” says Colleen Philbin, the director of counseling and program development for Speak Up, a Radnor-based nonprofit that organizes evenings designed to get adults and teenagers talking to each other about things like mental health, social media and drugs. “The parents are scratching their heads about how stressed-out the kids are. And the kids feel some relief in being able to say: This is what I’m struggling with.”

“I see lots of Penn students and lots of kids from competitive high schools,” says a local therapist. “There’s a lot of ‘I’m only as good as my last test.’”

The struggle is real. In a recent national poll of more than 35,000 teens, 45 percent said they were stressed “all the time.” According to the Centers for Disease Control, the suicide rate for 10-to-19-year-olds rose 56 percent between 2007 and 2016. Meanwhile, in a survey last year, 64 percent of university undergraduates said they’d felt “overwhelming anxiety” in the previous 12 months. Little wonder it’s become commonplace for both college and high-school students to see therapists as a way of coping with stress.

“The practice as a whole has really seen an increase,” says Rachel Chandler, a therapist and social worker with offices on the Main Line and in Center City. “I see lots of Penn students and lots of kids from competitive high schools. There’s a lot of I’m only as good as my last test. There’s a lot of identity fusion with that. Their success really rides on this very arbitrary thing.”

Curiously, while observers say anxiety levels have risen among kids from all backgrounds, the problem is particularly visible among teens in the most affluent, high-achieving areas. Though kids from lower-income families face far larger, more concrete obstacles — poor schools, violence and trauma in their neighborhoods, limited access to higher education — it’s the kids with the seemingly endless opportunities who are most anxious about their futures.

It’s an irony my daughter Sarah says she and her equally fraught friends are well aware of. “We know we live in a bubble,” she acknowledges. “But where do you find the balance between ‘I’m being dramatic, my life isn’t hard’ … and invalidating your own feelings? You can’t just deny that you’re feeling it.”

No, you can’t. All you can do is try to understand it. And I’d argue that what we’re seeing here — and will continue to see, unless something significant changes — is what happens when the teenage brain collides with the world we adults have built over the past 40 years.

One day in December, about six weeks after Sarah’s SAT situation, I get together after school with her and two of her friends — I’ll call them Sophie and Paige — at another Main Line coffee shop. If “after school” suggests the girls’ heavy lifting is nearly done for the day, think again. All three of them are frequently up past midnight, doing homework.

It goes too far to say that Sophie, Paige, Sarah and many of their peers see their sole reason for existing right now as getting into the most spectacular college possible. But probably not by much. It’s what drives them to study so hard. It’s what informs their decisions about which activities to do and how they’ll spend their summers. And it’s what has their anxiety levels cranked up, many days, to 11.

“A lot of it stems from the idea of the ideal student or the ideal college applicant,” Paige says when we start talking about stress. “You have to donate to the homeless and be an astrophysicist and have a five-point-thousand GPA.”

And if you don’t hit all those marks? Well, the girls know rationally that life won’t come to a screeching halt, but that’s not how it feels. “I think you can talk to any kid and they’ll be able to say, logically, ‘I know going to Yale doesn’t necessarily make me smarter, better — it’s not gonna really determine that crazy-much about my future,’” Sarah says. “But at the same time, you still want it.”

Just where this need to achieve comes from is complex. Part of it, no doubt, stems from parental pressure. Sometimes, that coercion is overt. But not always. My wife and I, for instance, have never really emphasized grades with Sarah or her older sister — the message has been more Just do your best — but the other day, Sarah took my chill attitude and flipped it back in my smug face. “You give yourself such credit for not pressuring me,” she said, “but the truth is, if I got C’s and B’s, you’d definitely put pressure on me.” What’s more, she went on, the “do your best” message actually just increases the stress she feels, since if she fails, it means she isn’t capable. (Having a critically thinking child, I concluded as she made some very valid points, can be really annoying.)

Photo illustration by Michael Houtz.

But parental pressure isn’t the only source of the achievement anxiety kids feel. Just as daunting, it seems, are the expectations that girls like Sarah, Paige and Sophie have for themselves. Having been raised in educated, high-achieving and often affluent families, they imagine nothing less for their own lives. Sophie, for example, is interested in neuroscience, so getting into an elite college simply seems like a necessary step in the journey. “I feel like to do what I want to do, I have to get into a good college,” she says. “Obviously, I could get into a lower-ranked school and still get a good education. But maybe I wouldn’t get to do exactly what I want to do.”

Paige, too, has high expectations for herself, born of both ambition and obligation. One of her extracurriculars is volunteering at a school in South Philadelphia, and the experience has helped drive home to her the advantages she has. “I think I feel an internal pressure to do something great,” she says, “to use my education to do something great, like cure cancer. Do something for the greater good, since I’ve been given this leg up. I think that’s where I feel the need to excel and get all A’s.” The pressure isn’t just about succeeding in the future. Sarah says that working as hard as possible right now is the debt she owes for the opportunity she’s been given.

Now, in many ways, all of this feels, well, right, doesn’t it? That is: These kids have internalized the message that you should work hard in life in order to fulfill your potential and make a contribution to the world. Isn’t that good? Isn’t that exactly what we want as parents? As a society? The problem, alas, is what it means from a practical standpoint, and what it can lead to.

For starters, there’s the fact that Sarah and so many of her peers feel there just aren’t enough hours in the day to do all the things they’ve been told — or told themselves — they should be doing. AP and honors classes. Varsity sports. Clubs. Outside-of-school activities. Summer experiences that leap off the page when it comes time to fill out the Common App (the standard online application many universities use these days). None of it seems optional, so they do whatever they must to squeeze it all in. On some days last winter, Paige had a schedule that even a seasoned CEO with a full administrative support team couldn’t have handled easily. School from 8 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Service project at that South Philly school from 3 to 5 p.m. Rehearsal for the school musical from 6 to 8:30 p.m. A dance class from 9 to 10 p.m. And then, finally, after a shower and dinner, homework that often kept her up studying until 1 or 2 a.m.

“I didn’t have dinner last year with my family for, like, eight months,” she says, “which was not awesome.” Though she’s eliminated some extracurriculars this year to focus more on academics — junior year is said to be crucial when it comes to college admissions — Paige still survives on just five or six hours of sleep a night, as do Sophie, Sarah and many of their friends. (Sleep is for the weak, the girls crack.)

What makes the overscheduling even more overwhelming is the feeling that they must do whatever they’re doing nearly perfectly — quantity matters, yes, but quality matters even more! So they strive to earn all A’s, get elected captain of a sports team, snag the lead in a school show, and conquer student government. It’s little wonder they sometimes feel so stressed that they actually have physical symptoms.

“Freshman year, I got really bad stress-induced stomachaches,” Paige says. “I thought someone was ripping open my stomach, and I would have to go home. It sort of went away on its own, but it was not awesome.”

“We’ve had friends who’ve had ulcers — literally ridiculous things,” says Sarah. “Our friend gets these weird stress-induced migraines.”

“I haven’t had symptoms from anxiety, but definitely from lack of sleep I’ve had headaches for two weeks straight and felt dizzy or dehydrated,” says Sophie. “I think anxiety is also worse when you don’t sleep, and I’ve had shaking.”

One could probably make the case that many of the factors causing these kids to feel stressed — parents, big ambitions, busy schedules — aren’t really new; high achievers across the decades have dealt with, and been fueled by, similar challenges. But what’s new — what has turbocharged teenage life in recent years and arguably made stress and anxiety go viral — is the ubiquitous presence of technology and social media.

Like most kids these days, Sarah is rarely without her phone, even when she’s plowing through several hours of homework every night. While she’s of the opinion that social media is generally a great stress reliever — it’s a good break from schoolwork, she argues, and a place where she feels supported by her friends — not everyone (including some of those friends) agrees.

To begin with, there’s the constant sense of comparison — and subsequent unworthiness — that nearly all of us succumb to when we spend too much time on social. As with the need to get into Yale, the girls understand rationally that all the perfect images they see on their friends’ Insta feeds are highly curated and filtered. But that doesn’t lessen the insecurity that can arise from scrolling through them. “You’re comparing your bloopers with their highlight reel,” says Sophie. “It’s such a false image of what’s really happening.” The constant quest for likes and comments also takes an emotional toll: You feel great when you get them, lousy when you don’t.

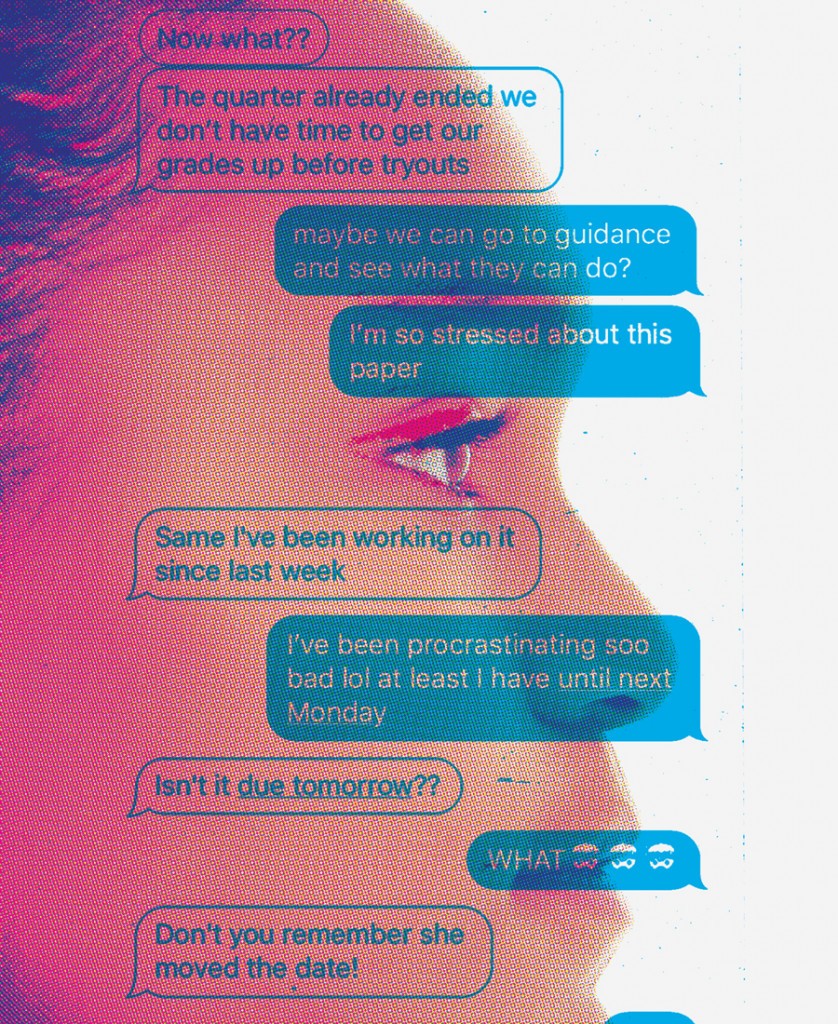

Another, even larger factor is the way social media and texting have given teenagers a 24/7 platform to share whatever they’re feeling in the moment — including stress from too much work and anxiousness about grades. This can be a good thing; it’s a way of connecting and coping. But the constant sharing has helped to create an adolescent culture in which stress isn’t just acknowledged or tolerated but, perversely, sort of celebrated.

Particularly last year, Sarah tells me, she and her friends engaged in lots of one-upsmanship — often expressed ironically but, you know, not really — about who was freaking out more and who had slept less and who was going to be the biggest failure in life because she was so going to get a 60 on this test. In my era, the game was to see who could get the best grades while studying the least. In Sarah’s world, it’s almost the opposite: who can get the best grades while suffering the most. The message they give each other: If you’re not dying, you’re not trying.

Sleep is for the weak, right?

Kids are caught up in a game that’s not really of their making and that they feel powerless to opt out of. At age 16, they seem kind of weary.

“It’s very much ‘How hard are you working?’” Sarah says. “How well can you do when you’re doing all these extracurriculars? Who can do the most? Who’s the busiest? And I think the competition really stems from, I want to be the best, but I want to be the best with the least to go on, if that makes sense.”

As I finish chatting with Sophie, Paige and Sarah, I find myself thinking a few things: how bright and mature they are. How broad their view of the world is. How self-aware they are. It actually gives me comfort and makes me think that despite the pressure they feel, these three girls, at least, are basically fine. Stressed but grounded. And yet, I’m also struck by how much they seem to be caught up in a game that’s not really of their making and that they feel powerless to opt out of. None of them seem bitter about that, but they do, at age 16, seem kind of weary.

“A lot of people say, ‘Live every day like it’s your last,’” Paige says. “And I’m like, if this was my last day, would I be doing any of this? No, I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t be with the people I’m with. I wouldn’t be sitting in the classes I’m in, probably. But it’s like, okay, you have to follow the path.”

“I feel like I can’t stop because it would look bad,” Sophie says. She’s about to head off to a dance class that, yes, she loves, but maybe loves a little less than she did back when she just did it for fun, before it became an Official Part of Her Résumé. She pauses. “I wish I didn’t have to live my whole life off the Common App.”

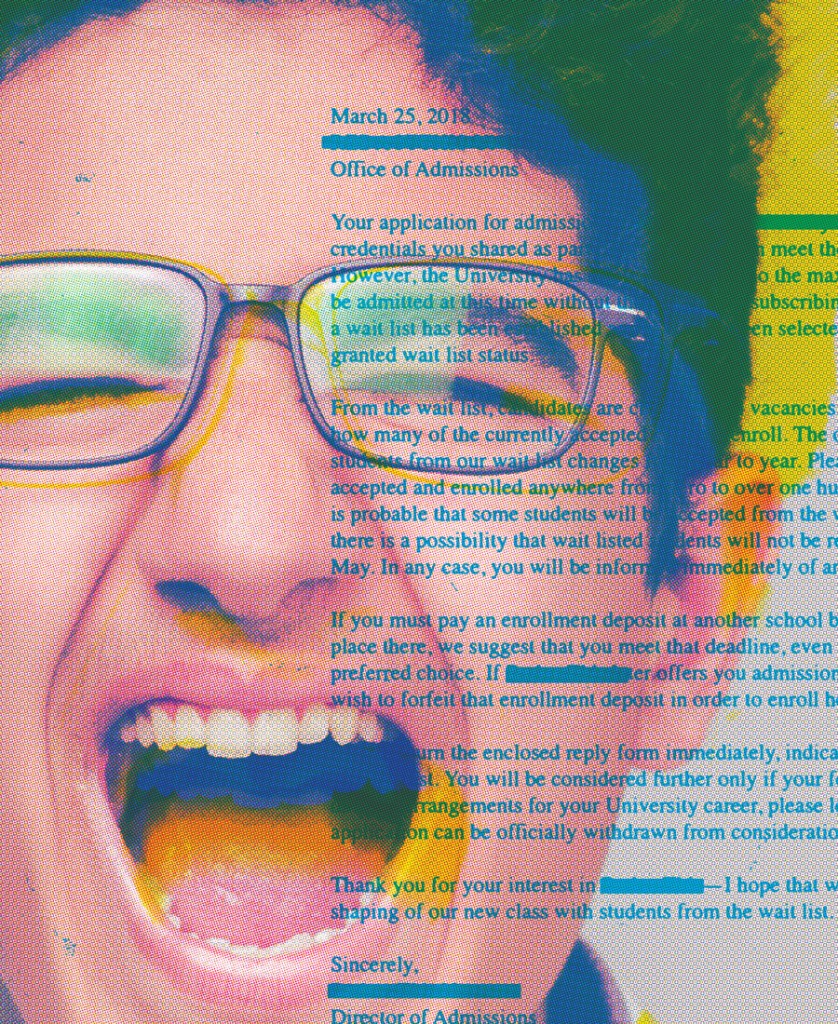

At the heart of Sarah’s and her friends’ anxiety is the understanding — or at least intuition — that the world is a harsher, more competitive, more stratified place than it was when I was in high school. The income gap has widened considerably in the past four decades, with those at the top seeing their earnings rise significantly while those in the middle and at the bottom watched their earnings stagnate or even fall. The best hedge against coming down on the wrong side of the have/have-nots line? Clawing your way into an elite college. Alas, that fact has only intensified what was already a fierce competition. In 1992, a decade after I graduated from high school, Penn’s acceptance rate was 39 percent; in 2018, it was eight percent, an all-time low.

The growing divide between the well-to-do and the less-well-to-do, between the meritocracy and the hoi polloi, isn’t only having an impact on how kids look at the future; it has coincided with — I’d argue has significantly changed — the way those kids have been raised.

For starters, there’s the fact that at least among the professional classes, being a parent these days can often seem less like a role you play than an important high-stakes project you’ve been given — yet another opportunity to show off your awesome competence. In contrast to the laissez-faire approach favored by previous generations, parents of my era are far more likely to put our trust in research and experts than in common sense and hand-me-down wisdom. We’ve loaded our kids up with structured activities — sports, camps, lessons — that we’re quietly betting will pay off in some kind of ROI. We constantly monitor their emotional well-being, not only attending every game and school performance but plowing down any obstacle we fear will jeopardize their happiness or self-esteem. Perhaps most significantly, we’ve elevated kids from an important part of adult life to the red-hot center of it: My world, dear child, is about you.

Because of that — and perhaps because of our deep-seated economic fears — we’ve subtly redefined the fundamental job of a parent. A role that used to be about shaping character and instilling good habits is now primarily about providing as much opportunity as possible. We flock to the best school districts or, if we can afford it, shell out handsomely for private schools. We hire SAT tutors and encourage our kids to take the tests, not once or twice, but three, four, five times. When summer comes around, our offspring don’t work at the local fast-food place; they land impressive internships or attend pricy summer enrichment programs at brand-name universities. In short, we do everything we can to give our kids an edge over anyone else they might be vying with when it comes to their own entry into the meritocracy. When the one-percenter music stops, we want to be sure our kids have seats.

None of this is necessarily bad, but we should at least be honest that it does have a cost. To begin with, there’s the fact that all our hovering and attention and structure can rob kids of having to figure certain things out on their own. There’s value in the pickup basketball game. There’s value in the miserable job. There’s value in the tough teacher. “One of the most important qualities a kid can develop is perseverance,” says Steve Piltch, the longtime head of Sarah’s school, Shipley. (He’s retiring this year after 27 years at the helm.) “I think sometimes we get in the way of that. When something not great happens, we want to solve it for them. Or when they don’t get the grade they want or think they deserve or we’d like them to achieve, we find fault with the teacher or perhaps the process. All of which could be relevant, but in the context of resilience … ”

At the same time, our current approach to parenting has — perhaps through our conscious choices, perhaps not — whittled the definition of what a successful life looks like down so far that it only seems to apply to a certain kind of high-achieving professional success. While it’s true that almost all the parents I know tell their kids the same mantra — You can be whatever you want; I just want you to be happy — I’m not sure that’s the message those kids receive when their every waking moment is geared toward achieving something or impressing someone. What’s that old expression — if the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail? For an elite 21st-century kid, everything surely looks like the Common App.

Finally, but maybe most importantly from an emotional standpoint, there’s the question of what exactly it feels like, pressure-wise, to be a child at the center of a child-centric world. “In a lot of our communities, family life is organized around young people having rich opportunities to perform and succeed,” says Speak Up’s Colleen Philbin. That’s great, but it puts a lot of heat on a kid. When it comes to sports, for instance, “Kids sometimes don’t tell parents when they’re injured,” Philbin says. “You don’t want to disappoint anybody. You know how much has gone into supporting you in this way.”

To be fair — and this, perhaps, gets us back to our hyper-competitive world — in many cases the structure and focus parents put on kids’ activities like sports grow out of something practical. The cost of college is astronomical, and in many families, a volleyball scholarship is the only way to swing it.

But it’s important to remind ourselves what all this feels like to a teenager. Martie Bernicker, the executive director of Speak Up, says that a few years ago, one of her four sons, then an eighth-grader, announced that he wanted to sing at church — not as a choir member, but as a cantor who leads the congregation. On the first Sunday of his new gig, Bernicker sat in the pew, anxious for him — and herself.

“I’m sitting there listening and thinking: I can’t believe I let this guy put himself out there; this is a pretty vulnerable position to be in,” she says. “And I’m thinking to myself: I should tell him he can get some lessons. But before I said anything, I stopped, because I remembered something that I’ve heard kids at Speak Up say.”

Which is? “We don’t even tell our parents what we like to do, because they want to make us do it better.”

Stress and anxiety aren’t inherently bad. Without some level of stress, most of us wouldn’t get off the couch every day. And a nervous edge before a big event or performance isn’t just natural; it’s probably beneficial, prepping our minds and bodies for the task at hand.

But there’s a difference, depending on your age, in how your brain reacts to stressful and anxiety-inducing situations. While a middle-aged brain like mine, in theory at least, processes input predominantly in the prefrontal cortex, using reason and logic, a still-developing brain, like Sarah’s or any teenager’s, deals with the world a little differently.

“The frontal part of the brain is not growing as quickly as the sex-drugs-and-rock-and-roll part of the brain, the amygdala,” says Taliba Foster, a psychiatrist who practices on the Main Line. “Executive function isn’t fully developed yet in a teenager.” Put another way: Because their brains are still growing, teens are essentially hardwired to react to the world more emotionally.

That’s a fact that’s helpful in understanding a lot when it comes to adolescents. It’s why they sometimes behave impulsively and take risks that drive their parents crazy. And it’s why, even though they understand things rationally — why a negative social media comment isn’t really the end of the world, and why a disappointing SAT score isn’t really the death of your dreams — they often react and behave as if they don’t understand that at all. In many ways, they’re still just kids.

For most teens dealing with stress and anxiety, the world is manageable. But in some kids, there can come a point where mental health issues become deeper, more serious and more debilitating. Panic attacks. Drug and alcohol abuse. Eating disorders. Cutting. Depression. Sarah’s friend Paige told me she could instantly count 10 kids she knows whose issues are serious enough that they’re in therapy. Sarah has told me of being concerned enough for a classmate that she approached a school counselor. In the last year, four Downingtown East High School students or recent graduates have died by suicide.

Photo illustration by Michael Houtz.

One day recently, I spoke to a woman I’ll call Meg. (She asked that her real name not be used.) She lives in an affluent part of the western suburbs, and she told me about her 17-year-old son, “Dylan.”

Dylan was always shy and socially anxious, she said. Though he had friends and did well in school, by eighth grade he was starting to withdraw — so much so that at the suggestion of a teacher at his public school, Meg and her husband switched him to a private high school. Though his social anxiety continued, he performed well academically and participated in activities. But then came junior year and the beginning of the college search.

“He started off fine,” Meg says, “but by November, he was really withdrawing from his friends, playing a lot of video games, watching a lot of videos online, spending a lot of time in his room.”

Matters grew steadily worse. By last January, Dylan was complaining of stomach pain and only going to school two or three days a week. By March, he was on medical leave, unable to go to school at all. The family tried a series of treatments — therapists, a psychiatrist, medication — but nothing worked. “He would come downstairs for dinner, but he would be counting the minutes until he got back upstairs,” says Meg. “The second he went upstairs, he would wrap himself in his blanket and just shut the blinds and withdraw.”

By late summer, Meg knew more drastic action was needed, so on the advice of some parents in a support group she’d joined, she began investigating wilderness therapy programs, which have become increasingly popular in recent years as a way of dealing with depression and behavior issues in teens and young adults.

She and her husband eventually chose a program in New England for Dylan, one in which he lived in an outdoor wilderness setting with six other teenage boys and two adult guides, plus met twice a week with a certified therapist. Dylan spent each day hiking, doing various tasks, and generally fending for himself in a way he never had before. “They have to learn how to light their own fires with flint and steel, and as they progress, they have to start a fire with a bow,” says Meg. “They have to pack their own packs, and they’re responsible for all their own gear. And they learn that if they don’t do it right, and it rains, your stuff is wet and you’re just out of luck. No mom is gonna rush in and dry your clothes for you.”

Meg says Dylan struggled at first, but as the weeks passed, he accepted where he was and what he needed to do. One key moment came when it was his turn to be the group’s cook for a week. After a long day of hiking, the boys are often ravenous, and that can mean a lot of stress on whoever is preparing dinner. The first time Dylan had to do it, he told Meg, it was difficult for him. He was meticulous. He didn’t like the pressure from the other kids. “But he sat and reflected on what was hard about it, and he said, ‘I’m kind of a doormat. I kind of let everyone walk all over me. And that’s one of my personality traits I’d like to change.’ And he did. He learned how to stand up for himself.”

Meg and her husband picked Dylan up in early December, after his 12 weeks in the outdoors. “He seems happy and settled,” she says now. As part of the program, parents participate in their own weekly counseling sessions with a therapist, which has made Meg reflect on the way she raised Dylan.

“As a parent, I kind of tried to shelter him from some of the things that are hard in life,” she says. “Anytime he would have anxiety — he was a socially anxious kid — I was like, well, you don’t have to go. So I didn’t really teach him resilience. And I also didn’t teach him that I thought he could do it. Kids need to meet adversity and win to have life skills.”

Meg says the experience has also made her think about the high-stress culture in which Dylan has grown up, both the obsession with college — teachers began talking to Dylan about it when he was in eighth grade — and the role parents play. “Parents think of their kids as an extension of themselves,” she says. “For them, it’s like a badge of honor. My husband and I were guilty of it, too. We were so excited when Dylan got his SATs back and they were so good. But now I’m like, you know what? That’s not about us. That’s his accomplishment.”

“I kind of tried to shelter him from some of the things that are hard in life,” says one local parent.

As for Dylan’s next step, this semester he’s enrolled at a boarding school. “He’s going to boarding school because I have a tendency to over-parent,” Meg says, “and we’re afraid we’re going to fall back into old habits.”

How we all move forward is tough to figure out. While stress and anxiety are issues that have an impact — sometimes a devastating one — on individuals and families, they’re ultimately societal and cultural problems whose solutions are far from clear. How do we reverse nearly half a century of growing income disparity and all that comes with that? How do we return sanity to a college admissions process that grows increasingly ludicrous every year? How do we undo decades of achievement-oriented mores? How do we defang social media? How do we persuade a generation of teenagers that life isn’t over if you don’t have a five-point-thousand GPA?

The situation, as Paige might say, is not awesome.

Maybe the only step we can take is to focus on our own lives. Colleen Philbin and Martie Bernicker of Speak Up believe there’s surprising power in simply talking and listening to kids.

“I can tell you what teenagers ask for,” says Philbin. “One of the things that they love is to spend time with their parents doing stuff that’s not related to accomplishing anything. They like to watch TV. They actually like to have dinner as a family, as long as they’re not talking about things that have to be done in school, specifically. And they like having their parents as people they can vent to instead of people who are solving their problems or judging them for their world.”

Just as important — though probably far more difficult — is for parents to remind themselves that kids are people, not projects, and that the teenage brain isn’t yet an adult brain. “There’s so much preparation for adulthood right now,” Philbin says. “The life of a young person isn’t really about being the best young person you can be anymore, the best teenager you can be. The job of a kid,” she insists, “is to be a good kid. Some of that’s lost on us right now.”

That doesn’t mean coddling anybody. On the contrary, it means giving kids age-appropriate responsibilities — and letting them fail, if that’s what happens. It means backing off and letting them figure some things out for themselves. It means reminding ourselves that over the long haul, there can be as much value in a crap summer job as in an expensive summer enrichment program.

All of this, given the current climate, is easier said than done. The day after I met with Sarah and her friends, colleges across the country sent out acceptance and rejection letters to applicants who’d applied early-decision. It’s a strategy that’s used increasingly by elite kids because it often ups their chances of getting into a great school. As we sat at our dining room table that night, I watched how excited Sarah was for kids a year older than she is who’d been admitted to terrific schools like Penn, and how disappointed she was for a couple of other friends who’d been deferred at Brown and Dartmouth. To be honest, I found myself slightly annoyed, in that very dad kind of way, at how invested she was in the entire thing.

But I’d be a liar if I didn’t acknowledge how invested I am myself. Just a month after Sarah took the SAT the first time, she took it again. Her score went up 100 points.

I hated how proud I felt about something that had so little to do with me.

Published as “Overwhelmed” in the February 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.