Q&A: Feminist Writer Rebecca Traister on How Anger Shapes Philly Politics

Traister, who grew up in Abington Township, will discuss her book Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger at the Penn Book Center on Saturday.

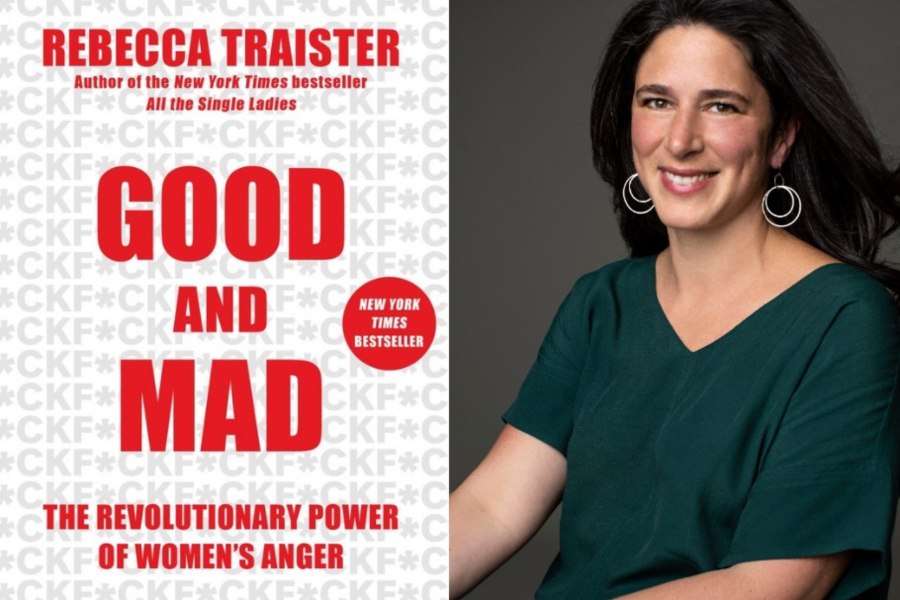

L: Rebecca Traister’s Good and Mad, published by Simon and Schuster | R: Rebecca Traister photographed by Victoria Stevens

Rebecca Traister is one of the most sharp-witted, observant feminists of our time. Her recently released book, Good and Mad, centers on women’s anger. Its 250 pages present a new cannon of women’s history, one that reanalyzes our nation’s major events to reveal how they’ve been shaped by women — and often by angry, righteous women who were, and continue to be, overlooked by men.

Traister, who lives in New York but was raised in the Philadelphia area, is also a writer at large for New York magazine and a contributing editor at Elle. She is set to discuss Good and Mad with Associated Press reporter Errin Haines Whack at 2 p.m. on Saturday at the Penn Book Center. We caught up with her beforehand to hear about how Philly has shaped her work, as well as what’s next for women and politics on a local and national scale.

Tell me a little about your relation to the Philly area.

I grew up in Abington Township. My parents still live there. I went to Glenside-Weldon school, which no longer exists. Then I attended the Abington school district through sixth grade and Germantown Friends School from seventh to 12th grade.

Now, I’m in Philly easily once a month. My husband and I will leave the kids with my parents and spend time in Center City. That’s the closest we can get to a getaway, staying at a hotel and playing around in Center City.

What’re some of your distinct memories of your childhood here?

Sonny D’Angelo, the butcher, and Di Bruno’s, when it was just in the Italian Market. The cheese shop in Germantown.

Has Philly affected your work?

Where I grew up, Glenside, was not at all progressive in the ’80s. It was a very Republican town. One of my memories is of the 1984 presidential election. I was in fourth grade, and I was the only person in my class that voted in a straw poll for [Democratic candidate Walter Mondale and his running mate, Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro].

I was extremely conscious that my politics were different than the politics where I was growing up, and I didn’t know a lot about city politics. Then I went to Germantown Friends School, where we talked steadily about progressive politics. That was a place where I began to think about racial and economic inequalities in new ways, as well as gender inequality.

Your book addresses women’s anger at a moment when, in the words of writer Elaine Blair, anger is the overall mood and political style. It feels like Philly is and has been one of the nation’s angriest cities. What’re your thoughts on that?

Well, it’s interesting, because many cities have been seeing a rise in protests. I think urban areas, where you have people who are keenly aware of the inequities people face — cities with diverse populations, economically and racially — are where you see a lot of disruptions and protests. You’ve seen an unprecedented rise in many cities, and I don’t know that it’s distinct here, though everything in Philly has its own spirit. It’s always been a politically and socially intense city. In my youth there was tremendous unrest in terms of mayoral politics, with Frank Rizzo and Wilson Goode, who bombed his own city. I also see Philadelphia as a place where a lot of leftist politics are being expressed, particularly with [District Attorney Larry Krasner], who ran such an exciting campaign. Philly is one of the places where we’ve seen an expression of the politics of this moment.

You could also say that women’s anger is translating here. Four local women will head to the U.S. House next year. Looking ahead to future elections, what kind of candidates do you want to see?

Pennsylvania has an abysmal record of women in politics — we’ve never had a woman governor or a U.S. senator, which is really embarrassing. What I’d like to see in Philadelphia and more broadly in Pennsylvania is a new generation of female candidates appearing in U.S. senate and gubernatorial races.

In the very beginning of Good and Mad, you make a point to identify yourself as a white woman. Shortly afterward, you write about how many organizers of the 2016 Women’s March, particularly white women, were unaware of the 1997 Million Women March, which was organized in Philadelphia and led by women of color. Can you talk about these two points?

I don’t think there’s any way that we can talk about the contemporary iteration of a women’s movement without tackling the racial inequality within it and the class inequality within it. I don’t think that it should be just women of color talking about race. White women need to acknowledge our race and our whiteness and do the work. That means recognizing that white women have come into movements where women of color have already done so much of the ground work.

Philly has a large population of independent and third-party voters. Are we going to see more voters like these in the future? And what might that mean for Democratic candidates like Hillary Clinton, who have worked their whole lives to overcome obstacles to rise within their party system, and then suddenly feel like that system is unacceptable to young, enraged voters, especially women?

Part of what we’re seeing with the 2018 midterms is a move to change the system. Hillary Clinton entered a system, years ago, that was run so much by white men. When you have young people in power — I’m thinking of Ayanna Pressley, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — this young incoming class of women is saying, ‘Wait, this system doesn’t have to be run by white men.’ And then you have these political groups that are trying to bring new kinds of candidates into electoral politics, people who are working to re-enfranchise people — as they did in Florida. You can’t just wish away the system and the inequities it’s been constructed on, but you can work to alter that system, and I think a young Hillary Rodham today would have a very different path than when she entered politics in 1968.

Last question. You wrote this book in four months. Are there any major issues happening right now that you wish you could’ve included?

Every day. Because once you start to see patterns of how women’s anger is dismissed, you realize that it happens around us all the time.