Are Philly Streets Any Safer After a Year of Vision Zero? We Look at the Report.

The ambitious initiative is progressing — but we’ve still got a long way to go if we want to reach zero traffic deaths by 2030. Here’s what you need to know.

The Vision Zero protected bike lane pilot program on Market Street and JFK Boulevard opened in June. | Photo by Claire Sasko

It’s been one year since the city launched Vision Zero, its plan to completely eliminate traffic fatalities by 2030.

Official released on Friday morning a report detailing the project’s progression — as well as areas where efforts have fallen short.

The major takeaway? Philly saw fewer traffic-related deaths and severe injuries since the launch of Vision Zero. However, if fatalities continue to occur at the same pace they have been, we won’t reach our goal of zero deaths by 2030.

Officials say it’s still possible, though: Through measures like improved road infrastructure, educational initiatives, and policy changes, they believe that the city can slowly chip away at its number of traffic fatalities — six deaths fewer per year, they hope — to get where they want to be.

Here are other takeaways from the Vision Zero one-year report.

- Philly’s streets are safer than they were a year ago. That’s largely thanks to a few ambitious new infrastructure programs: New bus plazas on Roosevelt Boulevard (a high-speed corridor); trash trucks upgraded with new safety features, including four 360-degree cameras and side guards (notably after Emily Fredricks was struck and killed by a private trash truck while bicycling on Spruce Street); and a protected bike lane pilot program on Market Street and John F. Kennedy Boulevard, which saw the installment of the city’s first bike signals.

- In addition, the Chestnut Street bike lane — the city’s first one-way protected lane, which opened in August 2017 — was evaluated, revealing a 47 percent reduction in the number of vehicles traveling on the stretch of the lane with speeds above the posted limit during morning commute hours.

- However, our streets are still far from safe enough. In 2017, Philly lost 78 people in traffic crashes, and 244 more sustained severe injuries in crashes. That reflects a 19 percent decrease in fatalities from 96 in 2016, but deaths are still occurring at a far higher rate than other major cities with Vision Zero policies: When it comes to traffic fatalities per 100,000 residents, Philly stood at 6.4 in 2016, while New York recorded just 3, Boston saw 4.2, Chicago saw 5.2 and Seattle saw 4.7. Los Angeles, which has notoriously deadly streets, came in just slightly higher than Philly at 7.8.

- The city figures that to hit our goal of zero traffic fatalities by 2030, we must reduce the number of related deaths in the city by roughly six each year. It’s going to take a lot of change — infrastructure, education, etc. — to make that happen.

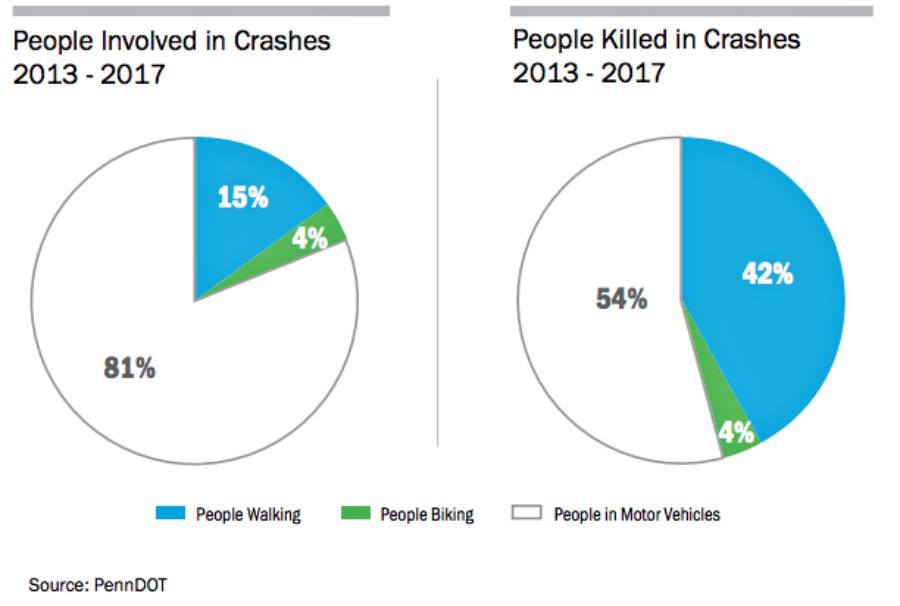

- Pedestrians are most susceptible to traffic-related deaths in Philly. In 2017, while 15 percent of crashes involved pedestrians, they made up nearly half of all traffic deaths. The city is hoping to combat this in the second year of Vision Zero by launching the Pedestrian Safety Study and Action Plan, which aims to identify trends in crashes and guide efforts to implement improvements.

- Overall, of the 78 people killed and 244 severely injured in 2017, 144 people were traveling in vehicles, while 87 people were walking and 13 were on bikes, according to the city.

Image via the Mayor’s Office

- Two of the slowest areas of progress? Bike lanes and local policy.

- Remember Mayor Jim Kenney’s goal to build 30 miles of protected bike lanes? Yeah, it’s moving along slowly. The city now says it’s aiming to install 40 miles of protected lanes by 2025 — an ambitious goal.

- Plus, out of all the areas where Vision Zero is tracking progress, efforts to change local policy are lagging. One major recent victory? Working with state legislators to gain approval for speed cameras along Roosevelt Boulevard, where 13 deaths occurred so far this year, as a pilot program. That was approved this month. But so far, the Mayor’s Office has yet to work with City Council to draft legislation authorizing the implementation of traffic calming/safety improvements though changes to road signage, markings and configuration — and it’s also yet to work with state legislators to gain approval for local control of speed limits (though the city did just announce that neighborhood streets around the city will have speed limits reduced to 25 mph, effective immediately). Plus, efforts to study implications of instituting stricter laws for injuring or killing pedestrians or cyclists within the right of way — like New York City’s Right of Way Law — are also moving along slowly. What can we say? Such is bureaucracy. But the city — and legislators — must do better to hit the Vision Zero goal.

- More is coming — expect to see new street infrastructure projects (and safer streets) in the next few years of Vision Zero. Last year saw the launch of several infrastructure projects, including the American Street Improvement Project (medians, shortened pedestrian crossing distances, and protected bike lanes on North American Street) and the Lincoln Drive Safety Program. Other forthcoming projects, which have secured funding and are expected to begin in the next three to five years, include raised medians on North Broad Street between Girard and Cecil B. Moore avenues, raised medians and improved sidewalks at South Broad and Locust streets, and a side path along South Broad Street connecting Pattison Avenue and the Navy Yard (which is probably welcomed by anyone who has ever tried to walk between the two).