The Looming DROP Apocalypse

Eight years ago, Philadelphians became outraged over the city’s wasteful and reviled retirement perk. And then Philly politicians ... didn’t fix it. As other cities around the country dump their DROP plans, can Philly muster the will to get rid of ours — before our pension woes swallow us whole?

Photo illustration by C.J. Burton

He was the only son of the Big Bambino, but even that couldn’t save him from the political firestorm over DROP.

Seven years ago, Frank “Franny” Rizzo Jr. was one of a half dozen incumbent City Council members who — under the city’s extravagantly generous Deferred Retirement Option Plan, or DROP — were eligible to “retire” for a day at the end of their terms, collect six-figure cash bonuses, and then, upon winning reelection (and making a quick trip to the bank), go right back to work the next day.

This being Philadelphia, it was all completely legal. DROP is the Council-approved retirement double-dip that lets municipal employees collect both their salaries and their pensions during their four final years on the job. The aim is to retain veteran employees and help the city plan for their departures. In Rizzo’s case, by way of example, it meant he drew not only his regular Council salary, an average of $106,103 annually, but also a separate lump-sum cash bonus payout that was deposited on his behalf into an interest-bearing account. The minute he retired, a windfall of $195,052 — plus his regular pension — would be his.

Outrageous? Voters certainly thought so.

In May 2011, Rizzo Jr., who had served as a Republican member of Council for 16 years, lost the backing of his party and ultimately finished seventh in a field of nine candidates in the GOP primary for Councilman at-large. Rizzo rightly pinned his defeat on DROP. He’d even asked for instruction on how to return the money when it became clear the issue was torpedoing his campaign. But city officials reminded him that the decision to retire under DROP was “irrevocable.” At the end of his term, Rizzo collected his six-figure DROP bonus and retired for real.

“They couldn’t attack me for not working hard. I worked seven days a week,” Rizzo recalls now. But taking the DROP “made me look as though I was greedy.” That, Rizzo says, left him vulnerable at a moment when his fellow Republicans were eager for a fresh face on Council: “Unfortunately, I set them up for success.”

Four other incumbent City Council members who took DROP money — president Anna Verna ($566,039), plus Jack Kelly ($384,828), Donna Miller ($185,572) and Frank DiCicco ($421,123) — decided to pocket the cash and stay retired rather than risk voter wrath. Just one Council member survived the DROP bloodbath: Marian Tasco, who, after winning that 2011 general election, retired for a day, collected a cash bonus of $478,057, then served another four-year term before finally retiring for good in 2015.

The loophole that allowed elected officials to get in on the fun has since been slammed shut by the state. But in 2011, in the wake of all the public outrage, City Council could have ended the entire DROP program for good. After all, the problem with DROP has always been bigger than a few pols walking out with wads in their pockets. Reporting I did in 2010 showed that DROP was costly — and draining the city’s flagging pension fund. In fact, in the wake of my report, then-mayor Michael Nutter proposed a bill to end DROP for all city employees. It never even made it out of committee. Instead, in a 15-2 vote in June 2011, City Council decided to keep DROP but “reform” it.

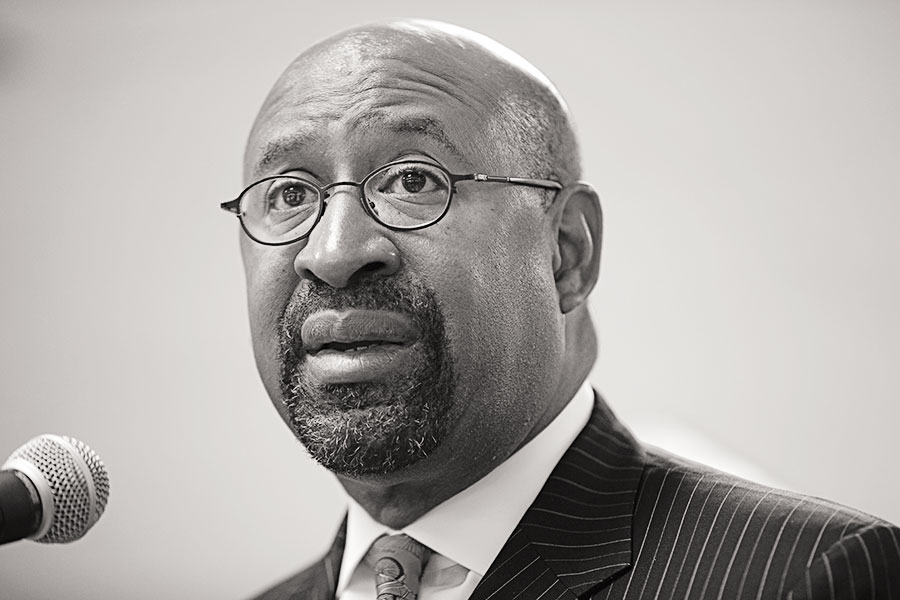

Mayor Michael Nutter, who tried to end DROP but couldn’t. | Photo: Associated Press

Unfortunately, seven years later, it’s clear that reform efforts did nothing to solve the fundamental fiscal problem caused by DROP—and some moves actually made things worse. Under the guise of reform, for instance, Council had the nerve to create a new perk that gave municipal employees another way to drain the city’s cash-strapped pension fund — one that 154 employees have taken advantage of, to the tune of $5.1 million. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Nutter, formerly the sworn enemy of DROP, quietly expanded the program by granting “extraordinary extensions” to 156 current DROP enrollees that allowed them to stay in DROP for a fifth year — and rack up even bigger bonuses.

The upshot is that today, DROP enrollment is up 32 percent over the past two years — and those retiring under DROP are checking out with higher average cash bonuses than ever before. And it’s all exacerbating strains on a municipal pension system so deep in debt that it’s absolutely crippling the city’s finances. Over the 19-year history of DROP, the total cost is staggering. From 1999 until April 28th of this year, the city has awarded to 12,411 municipal employees a total of $1.5 billion in DROP cash bonuses, or an average of $122,359 each.

It would be lovely if the city had all this cash to give away, but it doesn’t. Philadelphia’s municipal pension fund is classified as “severely distressed” because it’s only 45.3 percent funded. That means the city has just 45 cents for every dollar it owes in future pension obligations to 66,321 active and retired employees and their beneficiaries. (Actuaries believe 100 percent is the only healthy funding level for a pension plan.) And each big DROP payout only makes matters worse.

Here’s how bad it is: Our pension fund has $4.9 billion in assets but $11.3 billion in liabilities. Ultimately, in actuarial terms, that’s a $6.2 billion shortfall. For context, the entire city budget for the 2019 fiscal year is just $4.7 billion.

“We can’t kick this can down the road,” says Councilman Allan Domb. “There’s no more road. We’re about to go over the cliff.”

Who is on the hook to pay for that massive debt? The taxpayers, of course, who are already saddled with the cost of funding the city’s overly extravagant, unsustainable, and dangerously underfunded pension system. In fiscal year 2019, taxpayers will contribute $860 million to fund pensions — dwarfing the $709 million budget for the police department.

Mayor Jim Kenney, whose problem DROP is now. | Photo: Associated Press

Mayor Kenney has announced a plan to boost the funding of the pension system to 80 percent by 2030. But according to two financial experts, Kenney’s plan is unrealistic and “delusional.” Those experts say that because the city uses overly optimistic projections for the future earnings of its investments, the politicians down at City Hall are hiding the fact that the pension fund is in even worse shape than they admit. Indeed, it’s on the brink of disaster. The fallout from this overwhelming pension debt — the most flagrant symbol of which is DROP — could mean future cuts in services. It could also mean that the city, which has long struggled to fund its beleaguered public-school system, may be even harder pressed to pay for something as essential to its future as the education of its children.

DROP programs started out in the 1980s and ’90 in places such as Louisiana, Dallas and Baltimore. The idea was to entice veteran police and firefighters to stay in their jobs a little longer so they wouldn’t retire early and take their pensions to new jobs. There was also an altruistic aspect to the first DROPs—the sense that something special ought to be done for first responders, people who risk their lives to protect the rest of us. DROPs were consistently promoted, at least in theory, as cost-neutral.

But when DROP finally migrated to Philadelphia in 1999, altruism was replaced by greed. The trustees on Philadelphia’s pension board decided DROP was such a good deal that everybody should get in on it.

“It’s only fair. We’re all in the same boat,” John “Moon” Reilly, a firefighter on the pension board, told me back in 2003, when I wrote a story for the now-defunct Philadelphia City Paper. The Philly DROP might be egalitarian, but the expansion to include all municipal employees, even elected officials, is precisely why the boat is now sinking.

I first heard about DROP on a tip from a former city official. “It’s a scam,” Bennett Levin, the retired commissioner of the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections, told me. The program, Levin said, was cooked up by former mayor Ed Rendell when he was planning to run for governor and needed support from unionized labor.

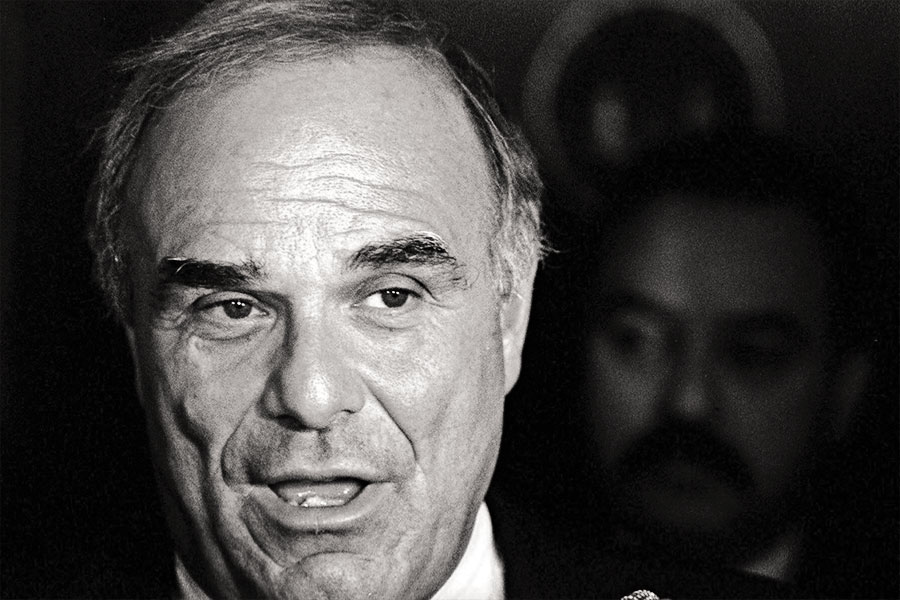

Mayor Ed Rendell, who started DROP. | Photo: Associated Press

Levin was particularly incensed because labor didn’t even have to go to the bargaining table to get DROP — it was a gift from the Rendell administration. Rendell, who declined to talk to me in 2003, was long gone from City Hall when he broke his nine-year silence on DROP. “If I knew then what I know now, obviously we wouldn’t have done it,” Rendell told the Inquirer on September 10, 2012.

Philly’s DROP began as an experimental program that would expire in four years if it resulted in “more than an immaterial increase” in pension costs. Then-mayor John Street told me he wanted to kill DROP. His finance director, Janice Davis, another early source in my reporting, dutifully told City Council members in February 2003 that they should get rid of DROP because the program was not only expensive — to the tune of $113 million in unexpected costs — but unnecessary. DROP was designed to retain veteran city employees, but Philadelphia didn’t have a problem hanging onto workers. Davis predicted that continuing the “widespread use of DROP” would mean that going forward, “a very high price” would be “extracted on the pension fund.”

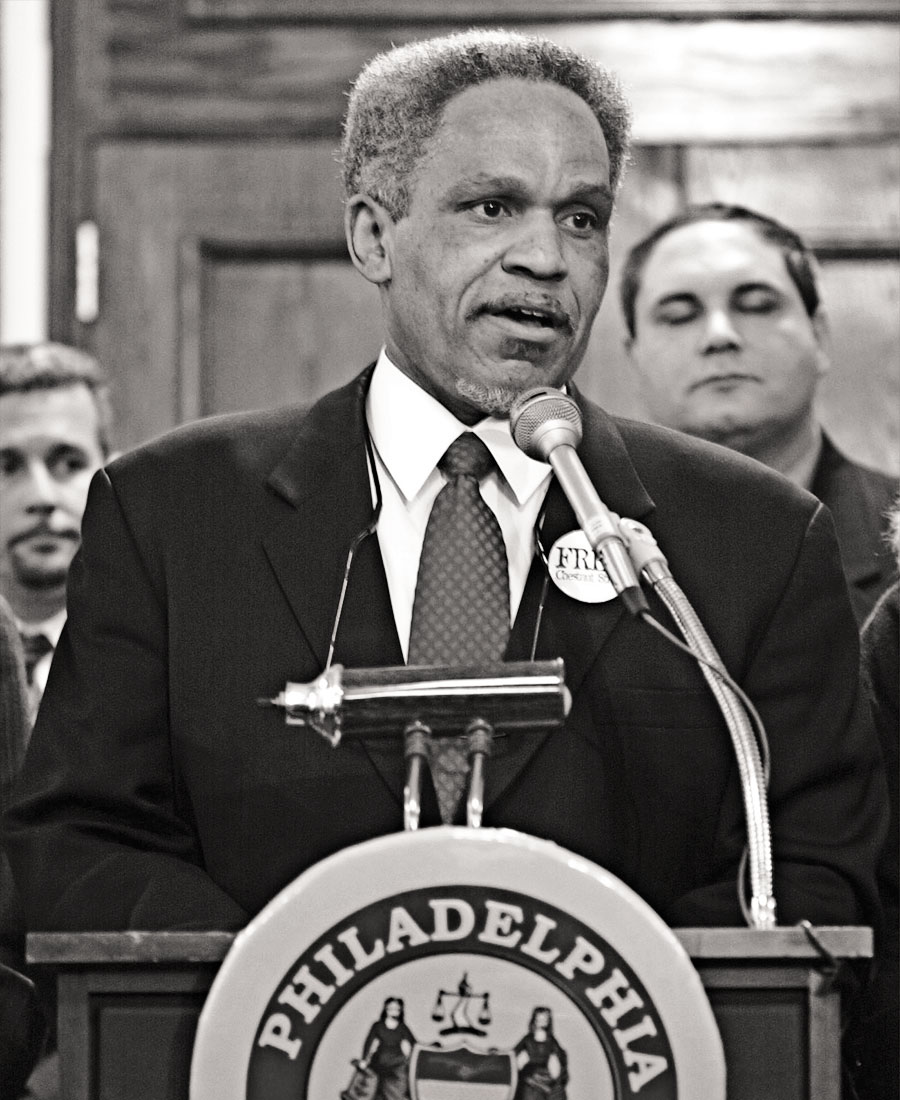

Mayor John Street, who wanted to end DROP but didn’t. | Photo: Associated Press

Davis was right, but the pension board didn’t listen. Instead, it voted in 2003 to make DROP permanent. And Street, who had previously told me, “We will ultimately end the DROP program,” eventually had a change of heart. (When he retired in 2008, he did so with a DROP bonus of $456,964.)

But it’s not just bold names like Street and Rizzo. DROP has been responsible for some truly memorable one-day runs on the pension fund thanks to less-prominent retiring employees. Take John Cerrone, a captain in the Philadelphia police department who on January 9, 2016, retired and left his job with a cash bonus of $493,411.

Also retiring that day: William P. Murtha, a captain of detectives in the DA’s office, who departed with a cash bonus of $482,691, and James D. Gould Jr., a police lieutenant who left with $457,916. All three cops spent five years in DROP thanks to “extraordinary extensions” granted by then-mayor Nutter, who, ahead of the Pope’s visit, determined that public safety would be impacted if the men retired after four years. (Nutter couldn’t be reached for comment.)

The list of the departed goes on. Cerrone, Murtha and Gould led a parade of 52 municipal employees who retired under DROP that day, collecting a total of $12.8 million in cash, or an average DROP payment of $246,861 each.

On June 29, 2013, Carl Ciglar, the deputy executive director at the city’s Parking Authority, retired with a DROP bonus of $539,343. He was part of a one-day exodus of 93 retiring city workers who collected a total of $18.8 million in DROP bonuses, or $202,313 each.

The record for the biggest one-day giveaway in the history of the DROP program was probably September 30, 2003, the day when the first big graduating class of DROP enrollees — more than 600 city employees — was scheduled to retire. City officials say they didn’t keep daily tabs for DROP-outs back then, but at the time, DROP payments were averaging $109,278 each, so the total payments for that one day amounted to estimated cash bonuses of $65.6 million.

This is, of course, perfectly legal under the pension system. But at some point, the wheels of the gravy train are going to fly off.

How was a program responsible for such big runs on the pension fund ever supposed to be cost-neutral? The idea was that participants get up-front cash bonuses in exchange for lower annual pensions.

When employees enter DROP, their monthly pension benefits are frozen, meaning they agree to forgo future increases in benefits that might accrue through raises and promotions. So DROP is just a trade-off, city officials say — those big cash bonuses are up-front payments on annual pension benefits that employees would otherwise be entitled to without DROP. With every cash bonus they hand out, officials maintain, the pension fund ultimately reaps a savings in the form of a cheaper annual pension.

But there’s no guarantee the pension fund will actually break even in that exchange. For example, when deputy managing director Susan H. Kretsge entered DROP in October 2010, she had more than 35 years of service and was paid an annual salary of $115,000. Another of Nutter’s extraordinary extensions, Kretsge spent five years in DROP. During that time, she was promoted and received several raises, boosting her pay to $169,740 when she retired in October 2015 at the age of 64.

But while she was in DROP, Kretsge’s future pension payments remained fixed at her 2010 level. That’s because the day she entered DROP, Kretsge’s pension was, per the city’s pension structure, frozen at 80 percent of the average of her three highest-paid years, or $90,271. Without DROP, her annual pension would have been $112,635.

So in the deal to collect her DROP bonus of $504,803, Kretsge gave up annual pension benefits of $22,365. But don’t shed too many tears. Thanks to DROP, she got another break. Employees who enter the program no longer have to contribute to the pension fund. For Kretsge, that amounted to an annual bump in her take-home pay of $3,774 while she was in DROP, or a total of $18,870.

In Kretsge’s case, it will take nearly 20 years for the pension money she would have earned without DROP to exceed the money she actually got paid under DROP—and for the city to come out ahead.

The outlook for that is not rosy. A Boston College study done last year said DROP has cost the city at least $237 million since its inception. (And elsewhere around the country, DROP programs have been found not to be cost-neutral as advertised.)

But that’s not the only reason DROP has been a big loser for taxpayers since day one. For starters, there’s a big hidden cost. While the city was running its generous DROP giveaway for the past 19 years, it was essentially giving away borrowed money.

Back in 1999, the year it started DROP, the city borrowed $1.29 billion by issuing pension bonds, at an interest rate of 6.6 percent, in what was, at the time, the largest municipal bond issue in state history. City officials have steadfastly maintained that this bond issue and DROP were unrelated. Without that bond issue, however, the city would never have had the cash on hand to give away all those DROP bonuses.

The bond issue boosted the city’s pension fund, which in 1999 had $2.9 billion in assets and a funding level of 52.3 percent, to $4.5 billion in 2000, and a funding level of 76.7 percent. That sounds good, but taxpayers have been paying off that bond ever since. For the 2019 fiscal year, our tab on that $1.29 billion note is $110 million. By the time the 30-year note is paid off in 2029, it will have cost taxpayers nearly $3.5 billion. But when actuaries, academics and city officials talk about the cost of Philadelphia’s DROP program, they don’t mention that bond issue.

The other ugly truth about DROP: When a pension fund is only 45 percent funded and saddled with sky-high costs — more on that later — it makes absolutely no sense to allow that fund to continue to hemorrhage cash in the form of six-figure bonuses. In fact, if the city were a business, under the safeguards of the federal Pension Protection Act of 2006, all lump-sum payments and credits for future service would have been cut off until the pension system’s funding level reached 60 percent. But since it’s a government program, Philly DROP rumbles on.

“Stupid,” and “symbolic” of deeper problems. That’s how Sam Katz — the three-time candidate for mayor who monitored the city’s finances as the chairman of the Pennsylvania Intergovernmental Cooperation Authority (PICA) — describes DROP. The program, he says, quite simply needs to be eliminated for all employees. DROP is “an easy target that needs to go — but it won’t go,” says Katz, the former CEO of a public finance and investment firm.

The only alleged advantage of DROP as a management tool is that it gives the city four years to plan for the future retirements of employees. That’s an expensive management tool. As Katz puts it: “Who gives away money when you’re $6 billion short?”

Another local expert on public-sector pension plans agrees that the city’s DROP program makes no sense. Bill Karbon, an actuary at CBIZ Inc. in New Jersey, advises the pension plan run by the Association of County Commissioners of Georgia, which includes 99 counties, as well the pension plans of 25 municipalities located primarily in mid-Atlantic states.

“I’ve never seen DROP used to this level,” Karbon says. “I don’t know why you would have such a broad-based DROP program.”

While Philadelphia officials extol the virtues of retaining senior employees, Karbon questions why any municipality would want to keep veteran civil servants on the job when they could replace them with younger workers at lower pay. “Encouraging employees to remain employed and then giving them the parting gift of the DROP doesn’t make sense,” Karbon says. “Why would you want to encourage employees in physically demanding positions,” such as police officers or firefighters, to stay?

Thanks to the lure of big cash bonuses, some municipal employees are staying longer on the job. That Boston College study found that with DROP, Philadelphia police were staying an extra 4.8 years on the job, and city firefighters 5.9 years. The effect on the retirements of non-uniformed employees was negligible.

The only way for the city “to stop the bleeding,” Karbon says, would be to eliminate DROP for all new employees.

In stubbornly keeping its DROP, Philadelphia is bucking a trend. Among the states and cities that have either frozen, limited or terminated DROP in the past decade: Alabama, Milwaukee, Dallas, Baltimore (city and county), Houston, Phoenix, San Diego and San Francisco.

Around the country, public officials, spurred on by angry voters, have gotten rid of DROP. Here in Philadelphia, however, DROP remains popular with municipal workers. Since 2016, the number of employees enrolled in DROP has jumped from 1,614 to 2,134 — an increase of 32 percent.

If those 2,134 employees currently enrolled in DROP follow the pattern of the past eight years, when DROP bonuses have escalated to an average payment of $142,026 each, they will cost city taxpayers an additional $303 million. That would bring the total tab for the DROP program in four years to more than $1.8 billion.

But eliminating DROP isn’t even under consideration in the administration of Mayor Kenney, the son of a firefighter. He’s been drawing a city paycheck since he first took office as a City Councilman back in 1992. In fact, Kenney was the guy who, back in the days of the experimental DROP, co-sponsored legislation that would not only have made the program permanent but would have increased the time employees could spend in it from four years to 10, which would have resulted, for the highest paid employees, in million-dollar cash bonuses. Fortunately for taxpayers, Kenney’s proposal went nowhere.

Now that Kenney is mayor, he’s certainly not going to do anything that would piss off the unions before he runs for reelection.

“The Mayor’s perspective is informed by the previous administration’s effort to eliminate DROP,” wrote Mike Dunn, Mayor Kenney’s spokesman, in an email referring to the losing campaign waged by Nutter. “As you know, that proposal was not approved by City Council, although Council did revise the program so that it is less costly.” (Council lowered the interest rate that DROP bonuses were accruing from 4.5 percent to the rate of a one-year Treasury note—which for 2018 was fixed at 1.76 percent.)

“The simple fact is that eliminating DROP would require an act of City Council as well as an agreement through collective bargaining for unionized workers,” Dunn continued. “It’s not something that can be done unilaterally by the Mayor. Because of that reality, this administration has focused on achieving other substantive pension reforms [through contract negotiations with city unions], including increased contributions from all employees and a capped pension benefit for new non-uniform employees. We also worked with DC 33 and 47 to lower the interest paid on DROP accounts to reduce the cost of that program. These changes will help the pension reach 80 percent funded by fiscal year 2030.”

As far as Kenney is personally concerned, Dunn added, “The Mayor has stated unequivocally that he will not enter DROP.”

Those recent changes enacted by the city, Karbon says, are positive developments. But Karbon is skeptical about Mayor Kenney’s plan to boost the pension fund to 80 percent funding by 2030, which kicks off by diverting $300 million in future sales tax revenues over the next five years to the pension fund.

“At this point, the city’s benefit payments exceed the level of contributions” made by city taxpayers and employees, Karbon says, looking at a 2017 actuarial report on the pension fund that shows $780 million coming in through contributions and $830 million flowing out in benefits payments and administrative expenses.

During years in which its investments perform poorly, Karbon says, the city “may have to liquidate investments at an inopportune time” to pay its pension obligations.

The stakes are high. The city’s revenue projections from investments are currently set at 7.65 percent per year; if actual returns are one percent lower, Karbon says, “liabilities could increase by 10 percent.”

The problem with public-sector pension plans, he says, is that “you’ve got elected officials with a short-term horizon making long-term decisions.”

Former PICA chairman Katz agrees.

“DROP is symbolic of how badly managed the whole pension system is,” he says. “The real problem is, we’re overestimating what we’re going to earn.” A lower investment projection of 6.7 percent, Katz says, would inflate unfunded liabilities to $6.9 billion and lower the funding level of the pension fund to 39 percent. As for Mayor Kenney’s plan to raise the pension fund’s funding level to 80 percent, Katz dismisses it as “noble but delusional.”

“The plan rises or falls on investment performance,” Katz notes. “Are you willing to bet on that for 18 years?” (The city says that a return of even 5 percent under the new plan would still raise the fund to 71 percent funded by 2030.)

Besides being in bad financial shape, Philly’s pension fund is extremely expensive. The traditional way to gauge pension costs is to calculate how much money a company or municipality puts into the system as a percentage of its payroll. In the corporate world, the acceptable range for pension costs as a percentage of payroll is between three and 10 percent. In Philadelphia, the cost of funding municipal pensions has nearly doubled in the past 20 years; as of 2017, it stood at 47.4 percent.

“That’s a very high number,” Karbon says. “I don’t think I have one plan that’s above 25 percent of payroll.”

None of the 125 county and municipal pension plans Karbon advises has a DROP. “I don’t do any DROPs, because they’re going to add to the cost of the plan,” he says.

But what ails Philadelphia’s pension fund is much bigger than DROP. “At the end of the day, their real problem was that [city officials] were irresponsible to let a plan get this underfunded,” Karbon says. “Because it’s so difficult to dig out of the hole.”

What’s led to this underfunding is a combination of overly generous benefits that far exceed the contributions made by employees and taxpayers and unrealistic projections for how the money invested in the fund will perform. Large lump-sum DROP payouts further decimate the pot.

“DROP just made a bad situation worse,” Karbon says, because it “creates an additional stress on a system that was already greatly stressed. … The city has a poorly funded plan with or without DROP.”

As far as Katz is concerned, the city’s pension problems are the result of a succession of mayors who negotiated affordable labor contracts that held the line on raises for union employees in exchange for increases in pension benefits. Eliminating DROP won’t solve the pension problem on its own, but eliminating it for new employees would be the first responsible step to stop that bleeding. Symbolically, it would send the message that Philly is serious about getting its act together on pensions.

If the city had only half its present pension debt, Katz says, it could contribute an extra $200 million annually to its chronically underfunded public-school system. Considering Philly’s oppressive tax structure, Katz adds, the way out of the present financial crisis is for the city to “monetize” its assets by selling off, say, the Philadelphia Gas Works or Philadelphia International Airport. In 2014, Michael Nutter proposed selling the Gas Works to a Connecticut company for $1.86 billion — but he couldn’t even get Council to hold a hearing on the plan.

So there you have it. Clearly, the responsible move for city officials is to get rid of DROP yesterday, then figure out how to address the mountain of pension debt.

“We can’t kick this can down the road,” says Allan Domb, the at-large City Councilman who’s emerging as that body’s voice of fiscal reason. “There’s no more road. We’re about to go over the cliff.”

In corrupt and contented Philadelphia, our public officials have previously lacked the will to do the right thing for taxpayers. They would rather keep that DROP spigot flowing so that down at City Hall, everybody stays happy. The only losers are the taxpayers stuck paying for a wasteful program that does absolutely nothing for them.

Domb, for one, has had enough.

“I think DROP is disgusting,” he says. Who needs a management tool that gives the city four years to replace a civil servant, he wonders, when “the president of the United States barely gets two months?”

Domb adds that if the city is really looking out for all 66,321 active and retired employees, and their beneficiaries, it’s irresponsible to treat the 12,411 employees in DROP to bonuses that amount to 30.6 percent of the pension fund’s current assets — in addition to their regular annual pensions.

Then Domb makes an announcement: “I’m going to introduce legislation to eliminate DROP for new non-union employees.” Non-union employees represent a small percentage of DROP enrollees, but it would be a start.

Domb is expected to introduce his bill to Council in late September. Whether his effort ultimately suffers the same fate as Nutter’s remains to be seen. But maybe, just maybe, the time is now ripe for this crusade to truly begin.

This story has been updated to include a response from the Kenney administration about the mayor’s pension reform plan.

Published as “The Looming DROP Apocalypse” in the October 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.