Nicetown Neighbors Continue Fight Against SEPTA Power Plant

A coalition of neighborhood groups is asking the city’s Zoning Board to scuttle the project, calling it “a continuation of obvious environmental racism.”

Out on Wissahickon Avenue in Nicetown sits a state-of-the-art recreational facility built with the (perhaps guilt-tinged) largesse of Joan Kroc, the late widow of McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc. When she died in 2003, Kroc left $1.5 billion to the Salvation Army for the sole purpose of establishing and supporting community centers where members can perform in the club jazz band, take leadership courses, and, maybe, work off those Big Macs.

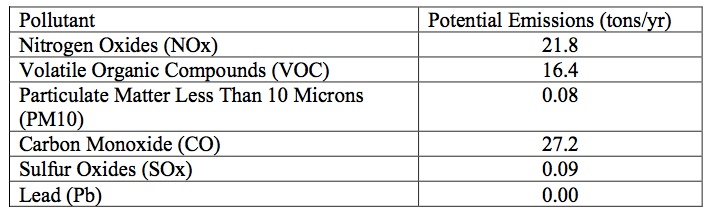

Right across the street from the Philly Salvation Army Kroc Center is SEPTA’s Midvale Bus Facility, part of the transit authority’s Roberts Complex and site of a proposed natural gas–fueled combined heat and power plant (CHP) that, according to SEPTA itself, would emit roughly 67 tons of toxic emissions into the air annually. That doesn’t exactly sound … healthy.

The plant has received preliminary approval for a building permit by the city’s Air Management Services office – an arm of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. But a ceremonial groundbreaking is not yet in sight, with a trio of community organizations having jointly filed an appeal to the Zoning Board — the next hearing of which is scheduled for Tuesday afternoon. Among the groups’ claims: “We consider this polluting proposal to be a continuation of obvious environmental racism, especially in Nicetown, but also Tioga and Germantown.” The demographics of the area where the plant will go is between 92 and 98 percent black.

“We know that our area was chosen under the assumption that we would not be able to organize resistance,” Lynn Robinson, director of one of the appellants, the Neighbors Against the Gas Plants, tells Philly Mag. “Nicetown and Germantown are low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods, and environmental issues have not traditionally been the loudest rallying cry in minority communities who have to contend with education, housing, and food insecurities, police violence, and more. But we suffer the most from negative environmental conditions so environmental justice is catching on.”

Neighbors Against the Gas Plants

In the simplest terms, the proposed plant is an eight-megawatt facility that will provide the baseload electricity for half of the Regional Rail system (the part that comes north from Jefferson Station through Temple University) and the bus garage, which is SEPTA’s largest. According to Erik Johanson, director of business innovation for SEPTA, the heat generated at the plant would also take care of the utility load for the complex.

“We describe this project as a win-win-win,” Johanson tells Philly Mag. “It will reduce our overall greenhouse gas emissions, generate electricity from cleaner sources than what the grid provides, and reduce the future risks associated with climate change. The win-win-win part comes from both of our main two goals being self-financed. This is not something that we’re paying for — it’s additive to our capital program.”

SEPTA is taking advantage of Pennsylvania’s Guaranteed Energy Savings Act to pay for the plant construction through the energy savings that the project would net. (The total cost of building the plant is just north of $25 million.) “The easiest way to describe it is a public-private partnership that pays for itself,” Johanson says. In addition to cost effectiveness, SEPTA says the plant would serve as a “resilient source of power” that would allow it to continue operating trains and buses even in the event of an outage by PECO.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Nicetown has a higher fine particulate level than 78 percent of neighborhoods across the nation, and more exposure to diesel exhaust than 90 percent to 95 percent of neighborhoods. In a 2012 report, the Philadelphia Health Management Corporation found that 31 percent of children living in the 19140 zip code were diagnosed with asthma – significantly higher than Philadelphia’s city average of 23 percent, southeastern Pennsylvania’s average of 18 percent, and the national average of 8.6 percent, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The emissions breakdown for SEPTA’s proposed power plant at its Midvale Bus Facility, from the agency’s May 2017 Notice of Application for Plan Approval.

In writing their appeal, the Neighbors Against the Gas Plants collaborated with two other Philly-based grassroots organizations – the Center for Returning Citizens and 350 Philadelphia. An overwhelming majority of members live within a mile radius of the Midvale Bus Facility or send their children to nearby schools in Nicetown.

“We believe that SEPTA has no immediate need for this project,” Robinson says. “The only viable motivation for SEPTA to build gas plants in Philadelphia is because they came under political pressure to buy natural gas before 2012, and then when they canceled a deal to convert their bus fleet to CNGs (compressed natural gas buses), they had to figure out another way to buy natural gas.”

Right to Clean Air

The appellants tout a state law stipulating that Pennsylvania residents possess a constitutional right to “clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic, and esthetic values of the environment,” alleging that SEPTA is in violation of this code. They call the project a “public nuisance” and challenge its designation as only a “minor source” of pollution, pointing to the plant’s equipment being designed for “major” output.

“We’re aware of the constitutional provision, but I’m not a lawyer so I can’t speak specifically to what the groups are alleging,” Johanson says. “Their position all along has been that SEPTA shouldn’t invest in tech other than solar and wind. We looked at both for this project and found that it could only produce 15 percent of the energy while running at approximately 100 percent. Renewable energy is just not a feasible approach to accomplishing what we want to do.”

According to Johanson, the Midvale Bus Facility is the site for this project and no other locations were considered. “The reason for that,” he says, “is because of the way the power system was designed.” All of PECO’s power is fed in through SEPTA’s Wayne Junction substation, which makes the complex the only available location for the new power plant.

While SEPTA has previously stated that the project received approval from both Air Management Services and the EPA, that fact remains in dispute. “For this specific site, EPA’s CHP Partnership was approached by SEPTA to review their results of the Partnership’s CHP emissions calculator tool,” an agency spokesman confirmed to Philly Mag. “The tool provides a comparison of CHP emissions and energy savings at a site against a comparable boiler used on site for heat and electricity used from the grid. The tool results review is independent of the formal regulatory permitting processes taken to design, install and operate such a system.”

As the appeals process continues to unfold, the Salvation Army is keeping close tabs on the fight of the Nicetown neighbors. “The Salvation Army is a charitable organization that focuses on meeting human needs and addressing community issues such as poverty, hunger and homelessness,” SA Pennsylvania spokesman Phil Pagliaro tells Philly Mag. “Regarding the proposed facility, there is a system and process in place that will determine the outcome. Thankfully, it involves professionals and civic leaders who are best suited to offer their knowledge, expertise and guidance to ensure that the end result is in the best interest for our community.”

Win-win-win?

When asked to respond to Johanson’s “win-win-win” comment, Robinson says she and her compatriots see no victory at all in building a natural gas plant in Nicetown.

“There is no win on reducing greenhouse gases,” she asserts. “There is no win on the project being a cleaner energy source than Pennsylvania’s energy grid. As our grid shifts away from coal and toward renewable energy, burning a fossil fuel for the next 20 to 30 years will lock SEPTA into an antiquated system. There is no win on reducing the risks of climate change, as SEPTA’s project will contribute to it for the next 20 to 30 years. We object to any public utility installing polluting projects in our city’s neighborhoods.”