The Re-Re-Re-Re-Rebirth of Atlantic City

When the casinos closed, everybody wrote it off. What if everybody was wrong?

Photography by Adam Englehart

John Longacre knows cool.

While most developers and real estate investors were running far, far away from the Point Breeze section of South Philadelphia, Longacre was busy opening one of its coolest restaurants, American Sardine Bar. Local IPAs. Vegan fried chicken sandwiches. Sweet-potato falafel. Twentysomethings with tattoos. Seven years after American Sardine opened, it’s hard to find a spot to lock up your bike most nights.

Longacre is also the man behind such cool and successful enterprises as South Philadelphia Tap Room; beer-nerd retail boutique Brew, with its hipster-approved garage-style doors; the year-old Second District Brewing; and the controversial Point Breeze pop-up beer garden.

But on this unseasonably cold and dreary day in early April, Longacre — a stocky 46-year-old with a penchant for craft beer — is about an hour southeast of his now-all-the-rage Point Breeze enclave, warning me not to trip and die.

We’re standing on the currently railing-less second-floor balcony of what used to be Club Deja Vu, a nightclub at New York Avenue and the Boardwalk in Atlantic City, in between Bally’s and Resorts. Deja Vu once pumped out house music at conversation-thwarting levels to guys in tight Ed Hardy t-shirts and girls in slinky dresses and strappy shoes. Drugs and booze flowed freely. Hookups ensued. For the moment, though, the thumping pulse of a subwoofer has been replaced by the sounds of a work crew that’s transforming the room into Longacre’s dream: a thousand-person indie music venue that he describes as the Union Transfer of Atlantic City, but with the intimacy of Johnny Brenda’s.

There’s a preternaturally ginormous disco ball in the center of everything. Longacre just spent a fortune on a sound system. Today, he’s trying to figure out just how big he needs to make the stage. The Anchor Rock Club, as it’s to be called, is set to debut in July.

“It won’t be nautically themed,” Longacre promises. “It’s ‘anchor’ as in the anchor of good things to come.”

The Anchor is just down New York Avenue from one of Longacre’s other good things to come, the old Morris Guards Armory, a 120-year-old, 30,000-square-foot architecturally stunning building that Longacre bought and gutted and is developing into lofty apartments with exposed brick and pipes. On the ground floor, retail. “It’s going to be like a smaller Reading Terminal Market,” he says.

Is John Longacre crazy? Union Transfer. Johnny Brenda’s. Reading Terminal Market. In Atlantic City?

He might be, but one thing’s for sure: Longacre is, as they say, all in. He’s channeling a big chunk of his resources into these and other Atlantic City projects. And he recently gave up his longtime Shore home in far less populated, far less grimy Sea Isle for an ocean-view place near the brand-new Atlantic City Boardwalk extension, just past what was once Revel. It’s mere blocks from a housing project.

“I spend all of my time down here these days,” Longacre tells me. “There is absolutely no reason that Atlantic City cannot succeed. It has everything that it needs to be reborn.”

People seem to either love or hate Atlantic City. There’s really very little in between. John Longacre is clearly in column A, as am I.

The city first drew me in about 15 years ago, when I was in my late 20s, thanks to the opening of the Borgata. At that point, most other casinos in Atlantic City were in various stages of decay, and here was this brand-new Vegas-style resort with casino restaurants that were actually good and the best shows in town.

These days, my travels to Atlantic City are more about the kids. My wife and I spend as much of the summer as possible on the A.C. beach with our 10-year-old and 12-year-old, opting for the relative solitude of the town’s southern end, far from any casinos or bars. We blow by all the suckers stuck in traffic trying to get onto the Garden State Parkway, sometimes making it in about an hour. Friends once tried to convince us to fall in love with Avalon, but it was, well … just too white, too artificial, too Stepford Wives. Last summer in Atlantic City, we saw a Muslim woman in head-to-toe black playing in the ocean with her toddler. If she tried that in Avalon, somebody would most definitely call the FBI.

John Longacre

John Longacre and I aren’t the only believers in Atlantic City. There are some surprising signs of life these days, not to mention some serious investment — from small ventures, like Longacre’s projects, to big bets like Stockton University’s new beachfront campus and this month’s opening of the $550 million Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in the old Trump Taj Mahal. And it certainly can’t hurt that in mid-May the U.S. Supreme Court allowed sports betting in A.C.

“There’s more money pouring into A.C. right now than in all of Philadelphia,” boasts development mogul Bart Blatstein. That’s likely an exaggeration, but it shows how much Blatstein — who’s scooped up a number of Atlantic City properties in recent years — is also all in.

“Atlantic City has risen and fallen innumerable times,” says Temple professor Bryant Simon, author of 2004’s Boardwalk of Dreams: Atlantic City and the Fate of Urban America. “This is the story that has been told for a hundred years.”

The irony, of course, is that this new resurgence is happening just a few short years after nearly half the city’s casinos went under, thousands of jobs disappeared, and Atlantic City itself seemed to be left for dead. Then again, maybe there’s no irony here at all. Maybe this more organic, up-from-the-ground rebirth of Atlantic City is exactly the kind of action that could mean sustained success for the city by the sea.

Atlantic City has always held a special allure for Philadelphians. In A.C.’s Nucky Johnson-Boardwalk Empire days, for instance, my maternal grandmother, a triplet, used to visit for multiple-birth conventions at which tourists would take pictures of her and her fellow zygotic anomalies. How very Atlantic City.

A couple of decades later, my mom spent a few weeks each summer with her aunt — one of the triplets — in an A.C. guesthouse. She loves to reminisce about those days, the era — the late 1950s — in which Frank Sinatra dominated the town and made it a true see-and-be-seen destination. (Alas, my mom never managed to bump into Frank.) The next decade, my professional-magician father, back when he was dating my mom, would do tricks on Steel Pier for tips.

It was right around this time that Atlantic City began to fade. Dissertations and books have been written about the many factors that led to the resort’s demise in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but a big one was the sudden ease of jet travel. You could get on a plane after breakfast and be on a beach in Miami for lunch. Atlantic City? Pfft. The Shore town began to disintegrate. By the mid-’70s, the city found itself at a pivotal crossroads. It could do nothing, ride out the downward trend, and see what happened. Or it could come up with some novel and wholly artificial way to inject new life into itself.

It opted for the latter, betting that gambling would be Atlantic City’s salvation. Until that point, Nevada was the only place in the United States where you could open up a full-fledged casino. But in 1976, New Jersey citizens voted to make slots and table games legit in Atlantic City. The first casino, Resorts — which just turned 40 and is still standing — opened less than two years later.

The 200 block of South New Hampshire Avenue

For a time, business was booming. The casinos can be credited with bringing hundreds of millions of tourists to the Boardwalk during Atlantic City’s gambling heyday. Some years, this city of 40,000 residents topped 34 million tourists. But outside the casino walls, the city struggled. The casino owners — including, for a time, Donald Trump — got fat, politicians got their kickbacks, and the impoverished residents of Atlantic City remained just that.

And then everything went wrong. The new Atlantic City created in the late 1970s was premised almost entirely on maintaining a casino duopoly with Nevada; once casinos started popping up all over — including in Pennsylvania in 2006 — Atlantic City imploded.

Things truly came to a head in 2014. Atlantic Club, which had opened as the Golden Nugget in 1980, fell that January, followed by Showboat. In September, the doors were locked at the $2.4 billion boondoggle known as Revel, which shamefully lasted just two years. A few weeks after that, Trump Plaza closed. Finally, in October 2016, one month before its namesake was elected to the Oval Office, the lights went out at Trump Taj Mahal. In just two and a half years, five casinos vanished, their cavernous buildings shuttered. Atlantic City had bottomed out economically in the most spectacular fashion possible.

Just like Northern Liberties bottomed out before William Reed and Paul Kimport opened the Standard Tap there, sparking new interest and new development in the neighborhood.

Just like Fishtown bottomed out before Johnny Brenda’s opened and young people and artists moved in.

Just like Point Breeze bottomed out before John Longacre came along.

When property values get low enough, neighborhoods like these are desirable and affordable to people like Longacre, who can now pick up buildings for pennies on a dollar. You wanna open a rock club? Sure, give it a shot. You want to try to emulate Reading Terminal Market on a sketchy section of New York Avenue? Go for it. Atlantic City suddenly became a risk worth taking.

Investing in Atlantic City now makes a lot more sense than it did five years ago, but it’s hardly a no-brainer. The city is overwhelmingly poor. (It has a 37 percent poverty rate.) Taxes are overwhelmingly high. And walking around on Atlantic or Pacific avenue — the two main north-south boulevards, which run parallel to and within blocks of the Boardwalk — can be nerve-racking after hours. In daylight, panhandlers accost and prostitutes solicit. Politically, things are hardly ideal: Then-governor Chris Christie instituted a state takeover in 2016.

“Every bank in the region is terrified of Atlantic City,” Longacre says. He tells me that not long ago, a banker he was working with drove through a neighborhood where Longacre is building homes; even after the tour, Longacre couldn’t persuade him A.C. was a smart investment.

In a sense, argues Longacre, A.C. seems almost designed not to succeed. “If you look at the policy surrounding everything that exists in Atlantic City, it’s the perfect storm to keep investors out,” he says. “From the state handling the zoning to the tax base to rent control, everything that happens from a policy level makes it seem like New Jersey is trying to make A.C. fail.”

But Longacre doesn’t believe it will fail in the long run, though he tells me it could be a good three years before the Anchor, for instance, actually makes him any money.

Longacre isn’t the only “small-time” investor betting on Atlantic City. A couple of weeks before I toured the Anchor Rock Club, I tagged along as another Philadelphia business owner was scouting locations for an Atlantic City extension of his immensely popular South Philadelphia bar. (He asked me not to name him or the bar because he wants to keep it under wraps until the paperwork is signed.)

We made our way through a smelly former strip club — close to the Boardwalk but in the middle of a block known as a major spot to score heroin. He passed.

We drove out to a freestanding building behind the Convention Center that was once a neighborhood sports bar, about a five-minute Uber ride from Bally’s. The building hasn’t been in use as a bar for several years, and when we visited, it housed hundreds of beach chairs and umbrellas for the owner’s beach-rental business.

“I love it down here,” the South Philly bar owner told me. “It’s so gritty … but in a good way. It’s so cool.”

A few years ago, the bar owner traded his Florida condo for a four-bedroom house a couple of blocks from the beach on the southern end of Atlantic City, about a half mile before Ventnor. He spends his summers between his suburban Philadelphia home and the beach house. In A.C., he grills in his backyard, goes to concerts, or eats in spots like Angelo’s Fairmount Tavern, Dock’s Oyster House, the Knife and Fork, Chef Vola’s and Tony’s Baltimore Grill — all iconic in their own right. (Tony’s is where he turned me on to his special order: a sausage pizza and a spaghetti with white clam sauce, hold the spaghetti. You dip the pizza into the clam sauce. It’s scary good.)

“The restaurant scene here is the best on the Jersey Shore by far,” he insists. He usually lunches at one of Atlantic City’s many Vietnamese restaurants, which the New York Times gushed over in a 2013 feature, deeming them “among the nation’s most authentic.”

Around the same time this South Philly bar owner got his place near the beach, Alexis Kull moved into town. The 30-something blonde, a sales rep for California-based mega-winery Gallo, had been living one town north, in Brigantine. But when she found a pristine waterfront townhouse in Atlantic City for under $300,000, she couldn’t pass it up. Her back door opens directly onto the water, where she has a boat and a jet ski parked at her two boat slips. “Anyplace else, a house like this on the water would have cost me close to a million dollars,” she says.

The daughter of a retired state trooper and sister to two current police officers, Kull says her friends thought she was completely out of her mind when she announced she was buying a house in Atlantic City.

“Everybody’s like, It’s not safe to live there!” she recalls. “I got so offended by that. I’m not an idiot. It’s like any city. You walk in Philly and you have to have your smarts about you. It’s the same thing here. This is not Margate. But it’s literally crazy to me that people think so negatively about Atlantic City.”

Kull and the South Philly bar owner are just two examples of the new breed of people who are now interested in Atlantic City — and who might help define its future. It’s not about Aunt Edna and Uncle Fred and their casino bus trips anymore. It’s about younger people who aren’t into Atlantic City for the gambling. It’s about people who don’t just feel comfortable in but desire urban environments, with all their flaws and character. It’s about people who respect and require diversity. It’s about people like me and my wife, who, to be honest, cringe when we drive into a place like Avalon.

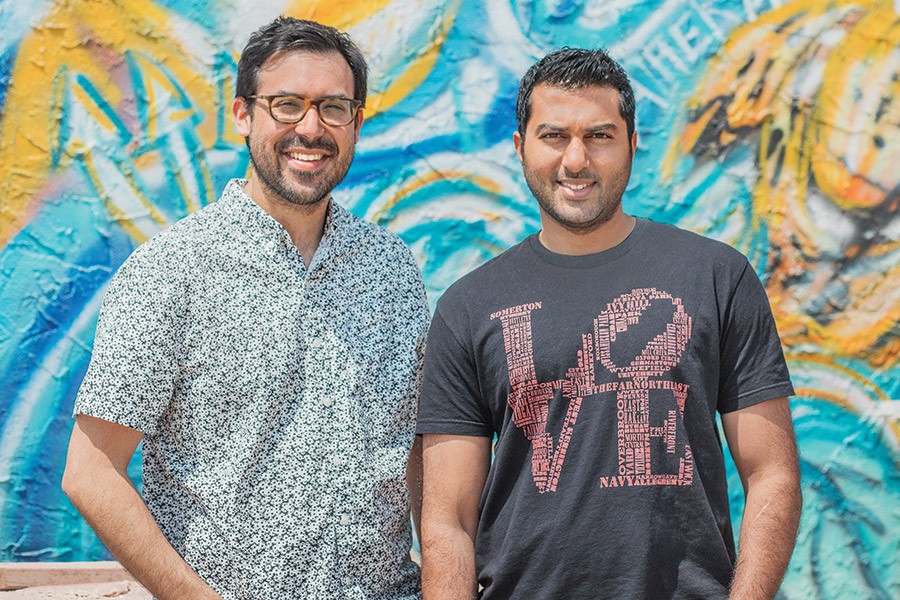

Evan Sanchez, left, and Zenith Shah

Kull bought her home when things were still pretty quiet on the development horizon. But now, everywhere she looks, there’s stuff happening. Over on Tennessee Avenue, a particularly desolate stretch of empty lots a block off the Boardwalk, there’s Made, a just-opened boutique chocolatier, right down the street from a yoga studio that debuted last fall. Both are part of a revitalization of the block being led by 34-year-old developers Zenith Shah, a Drexel grad originally from India, and Evan Sanchez, who got his B.A. at Columbia. Both men grew up in the Atlantic City area and are aware of the bad reputation of the block they’re now immersed in.

“People always ask us why we would choose Tennessee Avenue, of all places,” Shah says. “But this is beach-block. The ocean is right there. We see this as the most valuable piece of land in the most valuable city in Atlantic County. It’s Frankford Avenue 10 years ago.”

Shah and Sanchez are set to open a coffee shop on the block this month and a beer hall in late summer. “Living down here is a millennial’s dream,” says Sanchez, who left his NYC apartment for an Atlantic City townhouse. “Wake up, go surfing, grab a cup of coffee, get your work done, and then meet up for beers.”

Yes, things are definitely changing in Atlantic City.

What’s intriguing about A.C.’s current revival is the way small projects are being complemented by large ones. The Hard Rock Hotel is finally going to open on the Boardwalk later this month, where the Taj Mahal was until October 2016. Pottstown native Todd Moyer, senior vice president of marketing for this new outpost of the rock-and-roll-themed company, got his start in the casino business in 1990, when he worked as a tuxedoed greeter at, coincidentally, the Taj.

“I was working for Hard Rock out West when I got the chance to come home,” he says. “I jumped at it. Sometimes I would be at a bar or restaurant and hear people talking about Atlantic City being dead, and I’d jump in. I’m a defender and a giant supporter of A.C. We’re building hotels all around the world, but really, all the focus lately has been on Atlantic City.”

Yes, Moyer’s a marketing guy. What else is he going to say? But Hard Rock’s arrival in Atlantic City is significant, because while the property will have a casino in it, gambling is by no means the focus. Hard Rock is an entertainment company.

The Hard Rock name alone will undoubtedly draw a certain type of tourist to Atlantic City, and the resort says it’s going to be presenting hundreds of big-name shows each year to lure them in. Resort guests can choose to join a yoga class by the pool or on the beach or stay in their rooms and do yoga to original Hard Rock yoga programming on the TV, all underscored by Led Zeppelin songs, naturally. Or you can pick up your room phone and have someone deliver a retro-style turntable with built-in speakers, along with a handful of actual vinyl.

“We want to do everything we can to change the perception of A.C.,” Moyer offers. “This is a cool town.”

Then there’s the Ocean Resort Casino, which is taking the place of Revel. Its developer picked up the massive property — the last high-rise hotel on the northern end of the Boardwalk — for $200 million, an astonishingly small fraction of Revel’s original $2.4 billion price tag. When Ocean Resort debuts this summer, it will offer 1,400 hotel rooms, five pools, and an attraction that’s being billed as the world’s largest virtual golf experience.

“It’s about to explode down here,” Kull says when I ask her about the new casinos.

John Longacre couldn’t care less about casinos. “I’d love for every casino to go out of business and see Atlantic City re-create itself without them, as an urban beach town,” he says with a snicker.

Longacre might not be a fan of gambling, but there’s one massive Atlantic City development he says is a game-changer: Stockton. The nearly 50-year-old public university, which has its main campus in Galloway Township, about 20 minutes from the Boardwalk, is set to debut a brand-new beachfront Atlantic City campus this September. One thousand students will use the campus, and many of them plan to live in town.

“I’m already renting apartments to some of them,” Longacre tells me. “Stockton is huge. It’s the first real institutional investment in years that’s not a casino.”

Bart Blatstein agrees that Stockton is pivotal, but what he’s really excited about is that new Boardwalk extension, which opened just beyond Showboat (which he now owns) and Revel last year. “If you have not seen that new Boardwalk yet, you have to get down here,” he insists. “It’s so beautiful. You feel transformed out there.”

After Showboat closed in 2014, Blatstein didn’t waste any time grabbing it. He reopened the resort as a hotel — sans casino — in July 2016. Now, there’s talk he might bring gaming back inside. Around the same time Blatstein picked up Showboat, he also acquired the Pier at Caesars, the mall-like property that juts out into the Atlantic Ocean and houses restaurants that include Stephen Starr’s Buddakan and Continental as well as a sprawling Boardwalk-entrance candy store that my kids beg to go into whenever we pass by. The Playground, as Blatstein has renamed the complex, hasn’t yet helped Atlantic City reach the status he promised as, um, the “capital of entertainment on the East Coast,” but when you steal a $200 million property for $2 million, there’s plenty of breathing room.

Blatstein owns numerous other parcels and properties he’s not ready to talk about just yet. “Besides,” he says, “I’m one tiny piece of the many pieces down here. The money is just pouring in.”

Whether the gambles being made by Blatstein, Longacre and others are successful remains to be seen. Also unresolved is whether all the investment will put much of a dent in Atlantic City’s poverty rate or help the town’s current residents. And it’s not going to be this summer or next summer when we find out who, if anyone, wins.

But when I consider Point Breeze circa 2008 and that same area today, I have hope for this complicated Shore town. There will always be casinos here, for better or worse, and there will always be crime and poverty and grime. This is, after all, a city.

But 10 years from now, when my own kids are (I hope) in very good colleges, it’s not too hard to imagine us spending a summer weekend at some boutique hotel on New York Avenue. We’ll stop into the Boardwalk La Colombe for a draft latte, served up by a very hip-looking third-year Stockton student on break. For lunch, HipCityVeg down in the inlet. Happy hour will be at some John Longacre-owned brewpub overlooking the Atlantic.

And dinner? Well, for dinner we’re still going to Tony’s Baltimore Grill, for sausage pizza with a side of clam sauce — because some things will never change.

Published as “The Re-Re-Re-Re-Rebirth of Atlantic City” in the June 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.