“I’m Terrified”: Life on the Front Lines of the Sunoco Pipeline

They’ve put up with round-the-clock drilling and construction chaos. But after massive sinkholes began blooming in their yards, neighbors of the multibillion-dollar Mariner East project are looking for answers — and some are suing to stop it.

T.J. Allen at the boundary of the Sunoco Mariner East pipeline project. Photo by Claire Sasko

T.J. Allen was asleep when the second sinkhole opened.

He awoke one morning in early March and looked out the window at his childhood yard in West Whiteland Township, Chester County, where roughly a dozen strangers in orange and yellow vests stood around a fresh, gaping void in the earth.

In recent months, Allen’s home on the outskirts of Exton has looked nothing like it did when he was growing up, thanks to Sunoco and its parent company, Energy Transfer Partners L.P. (known for building the contentious Dakota Access pipeline). Since Sunoco began construction on its controversial Mariner East natural gas pipeline project in February 2017, Allen’s modest, quiet backyard — and his neighborhood — has become a chaotic construction site.

The property is split by the path of Mariner East 1, a cross-state pipeline built in 1931 that can transport up to 70,000 barrels of highly pressurized and volatile natural gas liquids per day. It’s also the future home of two more natural gas pipelines being built by Sunoco: Mariner East 2 and 2X, which will bring the ME pipelines’ total transfer capacity to 345,000 barrels a day. To get permission to build the two newer pipelines, the company negotiated easements with Allen and his neighbors in 2016.

“They said, ‘We’re doing the drilling — we’ll be in and out,’” Allen says. “‘You won’t even know we’re here.’”

Now, a year after construction began, Allen says his once quaint property has been turned upside down and plagued by sinkholes, intrusive workers, and mysterious security guards from out of state. He’s terrified for his life and ready to flee disaster at a moment’s notice — and he’s not alone. Last week, after a state agency shut Mariner East 1 down out of fear for public safety, three of his neighbors filed a class-action lawsuit against Sunoco, alleging similar claims. Sunoco, meanwhile, maintains that its own investigation of the site “has confirmed that at no time was our pipeline at risk during construction or operation.“

But some local officials agree with the Pennsylvania Public Utilities Commission’s assertion that an extremely lucrative, multibillion-dollar, 350-mile pipeline project approved by both state and federal officials has spawned a potentially “catastrophic” threat to those in its path. Allen and his neighbors worry that should something happen to the existing pipeline, their water systems could become contaminated — or, worst yet, their properties (and nearby Amtrak and SEPTA railroad lines) could go up in flames.

The kicker? Some say this entire anxiety-spurring mess could have been avoided in the first place.

A Spill, Sinkholes, and the Shutdown

When I visit Allen’s house on March 18th, his yard is covered in straw and hundreds of thin wooden posts mark the paths of the pipelines. His fence and the fences of his neighbors have been torn back or removed where they previously intersected with the pipelines’ paths. There aren’t any workers today, but two burly-looking security guards watch us from afar, standing near a pickup truck on Allen’s street. In the backyard, bright orange plastic netting separates us from the construction sites of ME2 and ME2X, as well as two sinkholes, which have been filled with concrete. The sinkholes are why I’m here — but they weren’t Allen’s first problem with Sunoco.

His initial trouble came on November 11th, when roughly 1,000 gallons of drilling mud leaked out of the ground in his yard. “I pull in my driveway, and the shit is just gushing,” says Allen, a 46-year-old independent contractor. “It’s like a river.”

The aftermath of the November 11, 2017, drilling fluid spill. | Via T.J. Allen

For days after the spill, dozens of workers (overseen by the state Department of Environmental Protection) filtered in and out of Allen’s backyard to clean up what Sunoco called an “inadvertent return” of drilling mud. That’s when he first noticed a sinkhole.

“No one would tell me how big the hole was or any other information,” Allen says. “I was basically shut out of my own property.”

Things quieted down for a few months. Then he says he saw a second sinkhole, bigger than the first, develop in early March. And a third — as wide as 15 feet and deep as 20 feet, according to the PUC — developed in a yard a few houses over. Here’s where major trouble came in: The third sinkhole exposed the bare, buried pipe of Mariner East 1.

Both sinkholes (filled with a concrete mix) in Allen’s yard. | Via T.J. Allen

Allen says he called the DEP, which eventually contacted the Public Utility Commission. On March 7th, the PUC shut down ME1, claiming its operation could pose a potentially “catastrophic” risk to public safety.

Sunoco and the state are currently conducting tests to determine the next steps for the Mariner East pipelines. The PUC is investigating the situation. Sunoco claims that each sinkhole, including the one that exposed ME1, was “immediately reported to the DEP as required, and addressed.”

“We have policies and procedures in place to address these situations when they occur, as was done in this case,” Jeffrey Shields, a spokesman for the company, wrote in an email.

In the meantime, Allen has created a disaster escape plan. After all, the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources wrote in a 2015 report to Gov. Tom Wolf (titled “Sinkholes in Pennsylvania”) that the “rupturing of natural gas lines by sinkhole collapse can have tragic results.”

Limestone and Lawsuits

On March 16th, roughly a week after the PUC’s shutdown of ME1, three of Allen’s neighbors filed a class-action lawsuit against Sunoco and one of its subsidiaries in Philadelphia County Court of Common Pleas. Mary March, Russell March and Jared Savitski claim that Sunoco’s construction has caused physical damage to their properties, lowered the value of their properties, and robbed them of their right to use and enjoy their land. They’ve accused the company of negligence, among other things, and are seeking more than $50,000 in compensation.

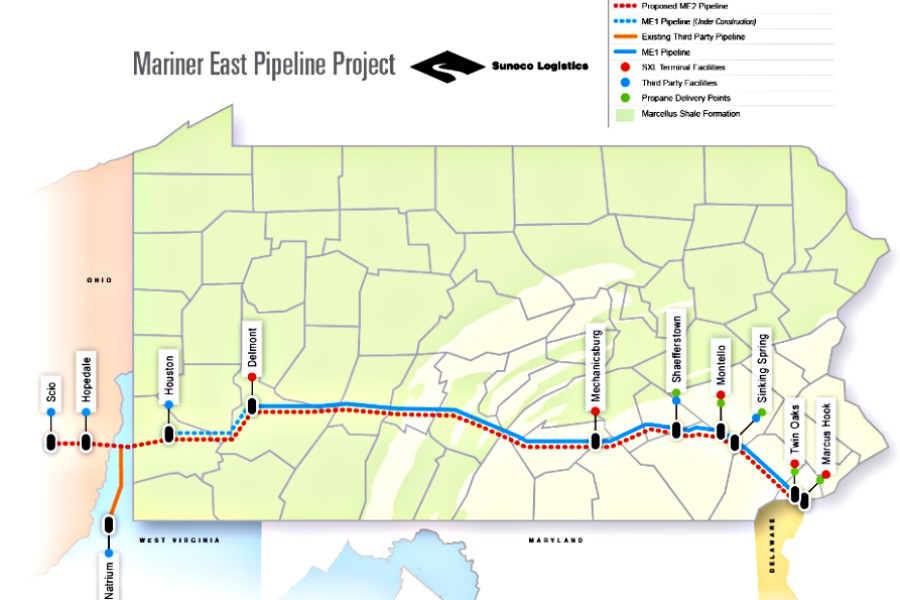

Some background: For most of its history, ME1 didn’t carry natural gas liquids. It transferred refined oil products until 2016, when it was repurposed to carry ethane and propane in an effort to cash in on Pennsylvania’s profitable Marcellus Shale region. The paths for ME2 and ME2X snake from Ohio through the Pittsburgh area and across southern Pennsylvania to Sunoco’s Marcus Hook facility in Delaware County, southeast of Philadelphia, on the Delaware River. They follow 80 percent of ME1’s existing route, including through Allen’s backyard.

Mariner East pipeline project route via Sunoco Logistics

In their lawsuit, Savitski and the Marches specifically reference Sunoco’s use of horizontal directional drilling (HDD) to install ME2 and ME2X outside their homes. HDD uses a mix of high-pressure water and bentonite mud (the drilling fluid that leaked onto Allen’s yard) to break up rock formations and soil in order to clear paths for pipelines.

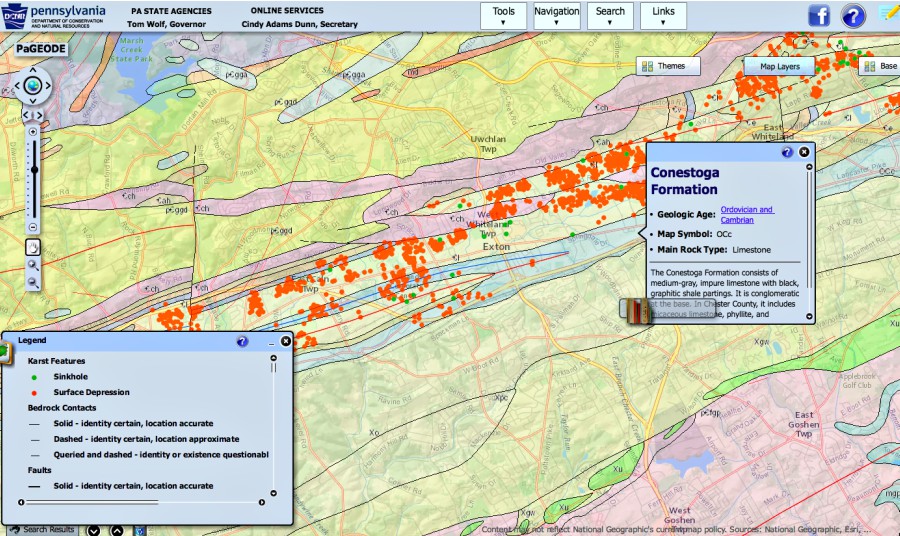

According to the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Allen’s neighborhood sits almost exactly atop a fault line where two rock formations — the Conestoga and the Octoraro — meet and form a fracture contact. Additionally, the Conestoga formation is comprised primarily of limestone, a porous structure that is prone to sinkholes.

Screenshot via the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources

Dr. Marie J. Kurz, a senior scientist at Drexel University’s department of biodiversity, earth and environmental science, says that limestone is slowly dissolved over time by rainwater (which is slightly acidic), and that erosion can be exacerbated by any process that increases the flow of groundwater — like HDD. For this reason, HDD is typically not recommended in areas dense with limestone — or near fault or fracture systems, for that matter.

“The area already has a propensity for sinkholes, but there’s a high potential that [HDD] has the ability to speed up the natural processes that form sinkholes,” Kurz says. “These aren’t tiny little bumps that someone is half-imagining — they are decent features. In the time frame reaction to the pipeline, it’s certainly very suspicious.”

In the complaint filed by Savitski and the Marches, they claim that an “underground fissure, void, fault or other change in the solidity and consistency of the subsurface rocks exists in the area of the March property” and that “Sunoco knew or should have known” of such an inconsistency prior to drilling.

“The failure to identify and avoid this fissure is a serious failure,” the lawsuit claims.

In an emailed response, Sunoco spokesman Shields said the company does not comment on matters related to current or pending legal issues. But the company maintains that the specific geology directly below Lisa Drive does not contain limestone.

“Professional geologists are always a part of the planning and operating of our pipelines, and ME2 and ME2X are no exception,” Shields wrote. “Construction through this area is safe.

“There is some karst [a rock structure that contains limestone] north of this area, but it does not impact this area. It is important to note that we have successfully conducted many drills in karst geology and many pipelines have been operating safely in karst areas for decades.”

Savitski and the Marches allege that using HDD methods near Lisa Drive caused the fluid spill in November, which they claim has spurred and could continue to spur potentially damaging sinkholes in the area. (They say that they have already noticed “cracking” in the walls, chimneys, and driveways of their homes.) They also fear that the spill may have “destabilized” the underground structure and water and sewer lines around the pipeline. In a worst-case scenario, residents say, they worry that if gas were to escape from the existing Mariner East pipeline, it could ignite and cause a “catastrophic” explosion.

An aerial view of Allen’s yard. | Via T.J. Allen

Andrew T. Neuwirth, a lawyer for the families, says they’re unnerved.

“These are small, cute, maintained developments with solid middle-class families,” Neuwirth says. “Now they’ve got drilling at all hours, diesel fumes all over the place, backhoes rolling out, jackhammers going and endless roughnecks from out of town parked [all over] their neighborhood. None of this would be necessary if a safer method had been used other than the one used by Sunoco.

“People are very concerned about their loss of property value. This is an up-and-coming area. A brand-new Whole Foods just opened up the road. Who’s going to want to buy a house on the sinkhole? Who’s going to want to buy something in the blast zone?”

A “Regulatory Breakdown”

The Lisa Drive episode is far from the only concern plaguing the Mariner East project. Since construction on ME2 and ME2X began, the work has damaged more than a dozen private water wells in Chester County. The DEP has issued the company 46 notices of environmental violations at sites across the state, and in January the agency ordered Sunoco to stop construction at certain sites (though not all). Roughly a month later, Sunoco paid a $12.6 million fine to the DEP (one of the largest civil penalties collected in a single settlement), and construction resumed.

State Sen. Andy Dinniman, a fairly moderate Democrat who represents the majority of Chester County, has been perhaps the Mariner East project’s most outspoken critic.

“Twelve million [dollars] is pennies considering the billions that are going to be made [because of the pipeline],” Dinniman, 73, said last week when I met him in his West Chester office. “While that sounds like it’s really cracking down, construction, to some extent, continued. Once [Sunoco] paid this fine, this pennies on the billions, they were given permission to proceed. That’s the point that drives me up a wall.”

State Sen. Andy Dinniman | Photo by Jose Mestre

The senator says the issue has enraged constituents across party lines. (Local Republicans like U.S. Rep. Patrick Meehan and State Sen. John Rafferty have also expressed dire concern over the pipelines.)

“I’ve been involved in politics for 25 years,” Dinniman says. “This is the largest grassroots movement I’ve ever seen in this area. The citizens are saying, ‘We now live in a state and in a country in which corporate interests are more important than our safety and our interests. Who do we look to for protection?’”

The corporate interest — and the state’s interest — are high. Sunoco claims that the pipeline project could generate a $9.1 billion economic impact in Pennsylvania. The company and Energy Transfer Partners LP insist that when construction is complete, the project will have supported more than 57,000 direct and indirect jobs between 2013 and 2019.

Gov. Wolf, who campaigned on enacting environmentally friendly policies, pushed for the DEP’s construction halt in January. But both state legislators and environmentalists say he hasn’t gone far enough.

Dinniman is calling on Wolf (as Meehan has) to see through an independent assessment of the Mariner East pipeline project, including a physical geological survey, and to use his power under Title 35 to halt construction of ME2 and ME2X until an analysis is completed. Residents of Delaware and Chester counties are so adamant about conducting an independent analysis that they’ve raised more than $18,000 via GoFundMe toward a $50,000 goal to fund the assessment.

“This area where the pipeline is going through is one of the most highly educated areas in the state, and [residents are] looking around and saying, ‘What’s going on?’” Dinniman says. “These are not radical environmentalists. These are not people who hang onto trees to stop bulldozers. These are moms and dads who are saying, ‘Is my kid in school being protected? Am I?’”

Senator Andy Dinniman addressing a standing room only crowd in West Whiteland. Citizen concerns: public safety, property values, property rights, all under attack by Sunoco, leakiest pipeline operator in the business. Thank you, Sen. Dinniman. Where’s Wolf? pic.twitter.com/9j6Dy2bZVN

— Eric Friedman (@EricFriedmanPA) March 4, 2018

During a legislative hearing on pipeline safety on Tuesday, PUC chairman Gladys Brown acknowledged that “there has been an increased public focus on the oversight of Sunoco and its Mariner East 2 project … with the public supporting the concept of having the Commission conduct a ‘risk assessment’ on the Mariner Project.”

Brown said the request “raises difficult issues,” seeing as Pennsylvania law requires the state to withhold some confidential information surrounding public utilities for security reasons. Still, Dinniman says, an independent analysis would better inform state agencies of potential risks.

The failure to prioritize such a study, Dinniman says, shows that “a corporation is controlling the whole show.” He and others question why the DEP and the state approved HDD methods in the area in the first place, knowing that the surrounding underground structure was prone to sinkholes.

“There is a regulatory breakdown — a failure,” Dinniman says. “This is no secret about the geology of the area. The state is fully aware because we constantly repair our highway system. This is absolutely the wrong area for [HDD]. The question is, why was this ever approved by the Commonwealth?”

In a statement, a DEP press secretary Neil Shader said the organization and other regulatory agencies “permit activities” in limestone-dense areas “rather regularly,” and that the DEP works to “address the unique issues associated with such geologic formations.”

“While the geology is more prone to sinkholes, it does not present unreasonable risk to permitted activity of all sorts,” Shader said. “Impacts from construction, such as sinkholes, are the responsibility of the operator, and DEP will continue to ensure that any impacts are fully remediated. DEP will work to ensure that any impacts are remediated by Sunoco, and can be avoided moving forward.”

Allen’s yard on March 18th.

For now, ME1 will remain out of service as the PUC continues its investigation of the site. A PUC spokesman said it’s not clear when more information will be released to the public.

T.J. Allen, meanwhile, says he’s frustrated that investigators haven’t spoken directly with him.

“They said they’re doing an investigation,” Allen says. “No one from the DEP or the PUC or any agency has knocked on my door and asked if I’m OK or asked anything. I find that irresponsible.”

Allen will wait to hear whether or not he’s safe — and if PUC will allow Sunoco to continue construction in his neighborhood or force the company to find another route. In the meantime, he’s put together a “go-bag,” with important papers, his wallet, cash, and the deed to his house.

“I’m nervous,” he says. “I have no answers. Any moment, I feel as though the pipe could break, or the house could sink, or I could look outside and see another sinkhole close to the pipe and have to leave. It’s a real threat.”