Philly Drivers, You’re Wrong: Protected Bike Lanes Will Actually Ease Congestion

Studies around the world — and on-the-ground experience in New York — show that separated bike lanes help move everyone faster. Philly doesn’t have to fall behind.

Courtesy of the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia

Last year, officials cut the ribbon across the city’s first and only one-way protected bike lane.

The opening of the 1.1-mile artery, which stretches east along Chestnut Street between 45th and 34th Streets, was not without controversy. After six years of intensive planning and careful community debate, the city councilwoman who approved (and helped arrange) the $50,000 lane said she was having second thoughts about it.

Why? Because despite the fact that the bike lane could save lives along one of the busiest and most accident-prone streets in the city, drivers grumbled over the fact that a car lane had been removed to build it.

While a city spokesman says the bike lane is here to stay, its creation renewed a common “bikelash” argument among Philly drivers, often punctuated with personal anecdotes: removing a car lane for bikers lengthens commutes and adds to traffic congestion.

The claim typically goes hand-in-hand with calls to block the building of protected bike lanes — an initiative at the heart of Vision Zero, the city’s pledge to eliminate traffic-related deaths and injuries. As part of Vision Zero, Mayor Jim Kenney has promised to build 30 miles of protected lanes. Right now, Philly is home to a paltry 2.5 miles — with plans for a few more in the works. In his annual budget proposal in March, Kenney called for the creation of a Vision Zero maintenance crew of 13 newly hired staff members who will be “dedicated to implementing a network of over 400 miles of bike lanes and traffic calming approaches throughout the City.”

Because here’s the thing: Adding more protected bike lanes – effectively separating cyclists from drivers – would actually work to unclog our city’s streets. And right now, that’s exactly what we need.

Changing Vehicles and Attitudes

In November, London’s public transportation organization fielded a question about whether the installation of a “cycle superhighway” (a.k.a. protected bike lane) worsened traffic congestion along Upper Thames Street, a major thoroughfare in the city’s historic and financial center. An agency bureaucrat responded by saying that the segregated cycle lanes were “moving five times more people per square metre than the main road, with … a more than 50 percent increase in the total mileage cycled.”

Note that the questioner had asked about traffic congestion — not auto congestion. It’s easy to confuse the two, especially in the U.S., where street planning has long prioritized cars over people. But attitudes are changing.

In Philly, car commuters are one of many players vying for precious space on our street grid, as Philadelphia magazine editor Tom McGrath recently explored. Today, cars must compete with buses, cabs, ride-sharers, delivery trucks, trash trucks, food trucks, construction vehicles, construction sites, double-parkers, trolleys, pedestrians, the occasional skateboarder, and yes, bikers. It’s the beauty (and the curse) of the city — a “chaotic ballet,” in the words of the Center City District, which issued an ominous report on traffic congestion in a rapidly developing Philly in late February.

Philadelphia has committed less and less money to basic street repairs and new traffic technologies, as traffic congestion has gotten worse. For more, download our new report: https://t.co/woeuJABb6T pic.twitter.com/WdsFhpGBrD

— Center City District (@ccdphila) March 8, 2018

As evidenced by the second thoughts over the Chestnut Street bike lane, officials like City Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell argue that protected bike lanes can lead to less space for cars — and, by extension, they reason, more congestion. But analysis proves otherwise.

One example (we’ll get to another one much closer to home later): A 2016 study led by researchers at Germany’s Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy (and funded by the European Union) monitored more than 20 cycling and pedestrian-friendly sites around the world — including New York — and found that “a modal shift from car traffic towards the more space-efficient modes of walking and cycling has the potential to reduce congestion.”

In recent years, urban planners across the nation have begun to shift away from car prioritization in favor of infrastructure that better supports urban life and its multitude of transportation options. In an article published this month in The Atlantic, Steven Higashide wrote that “it’s an increasingly basic tenet of urban planning that American cities must undo the car-oriented street designs of yesteryear.”

As Higashide details, this developing doctrine is reflected in federal and national road design guides, which in the past two decades have expanded to include protected bike lane guidelines (largely borrowed from Northern European countries), as well as additional tips on speeding up public transit and automobile traffic calming techniques. Philly, like many other U.S. cities, follows bike lane standards put forth by such guides.

Last year, the Federal Highway Administration acknowledged in a new set of traffic rules that the fundamental purpose of a road is to move people — not cars and trucks. The U.S. Department of Transportation essentially determined that the “success” of a road system is measured by how fast people are moving, instead of how fast cars are moving — meaning a bus with 50 passengers will be considered 50 times more successful than a car with one passenger, as the nonprofit PeopleForBikes argued. At the time, Stephen Davis, a spokesman for mobility advocacy group Transportation for America, told the nonprofit that the rule change could determine “how the discussion over congestion will be framed” in the future.

It’s an elemental concept that’s outlined in the Center City District’s recent congestion report, which ultimately “recommends that Philadelphia better coordinate the multiple modes that make a city a success – walking, cycling, automobiles, buses and delivery vehicles.”

Image by Center City District via NACTO

In doing so, the CCD offers a number of suggestions that align with the recent nationwide push to lessen car-reliance in cities, including traffic enforcement by civilians, the elimination of on-street parking during business hours, designated pick-up and drop-off zones for taxis and transportation network companies (an easy-to-implement, potentially revenue-driving solution), congestion pricing (which, as the organization says, probably won’t happen), and a fare-free transit zone for dedicated bus lanes.

The traffic-calming recommendations were embraced by the Bicycle Coalition, which, of course, had just one additional proposal: more protected bike lanes.

Build It and They Will Come

New York, the third most traffic-congested city in the world, has built 98 miles of protected bike lanes in the last decade. Polly Trottenberg, the city’s transportation commissioner, told the New York Times last year that expanding biking infrastructure in the city was a crucial step toward decongesting the city’s streets.

“We can’t continue to accommodate a lot of the growth with cars,” she told the newspaper. “We need to turn to the most efficient modes, that is, transit, cycling and walking. Our street capacity is fixed.”

Between 2005 and 2017, as more and more protected bike lanes were built in New York, the number of daily bike trips in the city outpaced both the city’s population and employment growth, according to the Times. Last year, bicycles began to outnumber cars on one of Brooklyn’s busiest commuter streets, passing more frequently per hour along the road’s spacious protected bike lane.

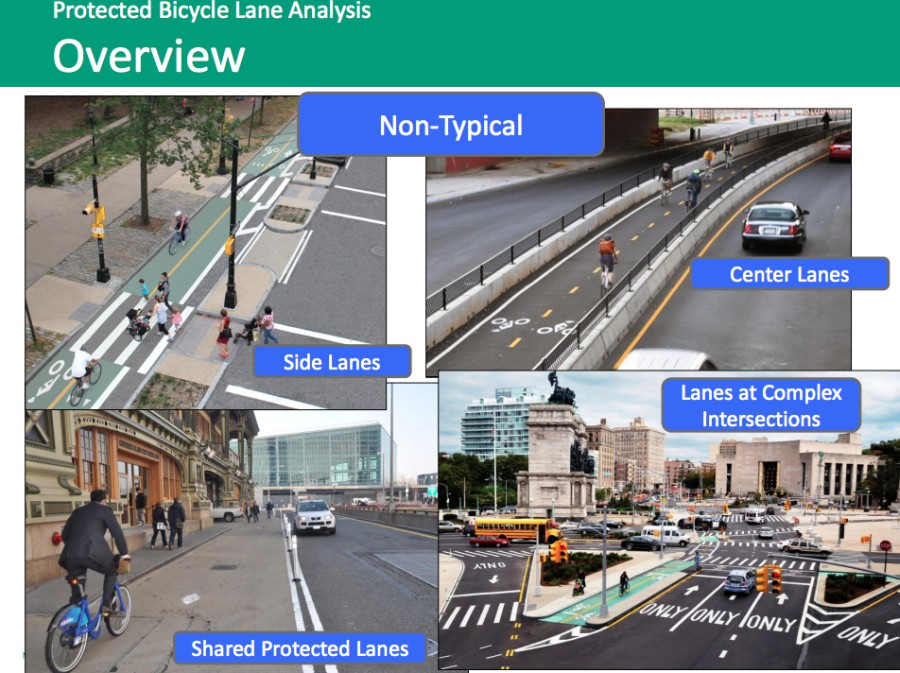

Examples of bike lanes installed in New York | Image via the New York City Department of Transportation

New York isn’t the only city that sees protected bike lanes as the future. Chicago now has 25 miles of protected bike lanes, Minneapolis has 15, San Francisco 16, Washington, D.C., more than 9. In each of those places, the share of commuters who bike to work has more than doubled since the city’s first protected bike lanes was implemented. Why? Because as studies show, people are more inclined to bike when they feel comfortable on the street. And to make people feel safe while biking, you need protected bike lanes.

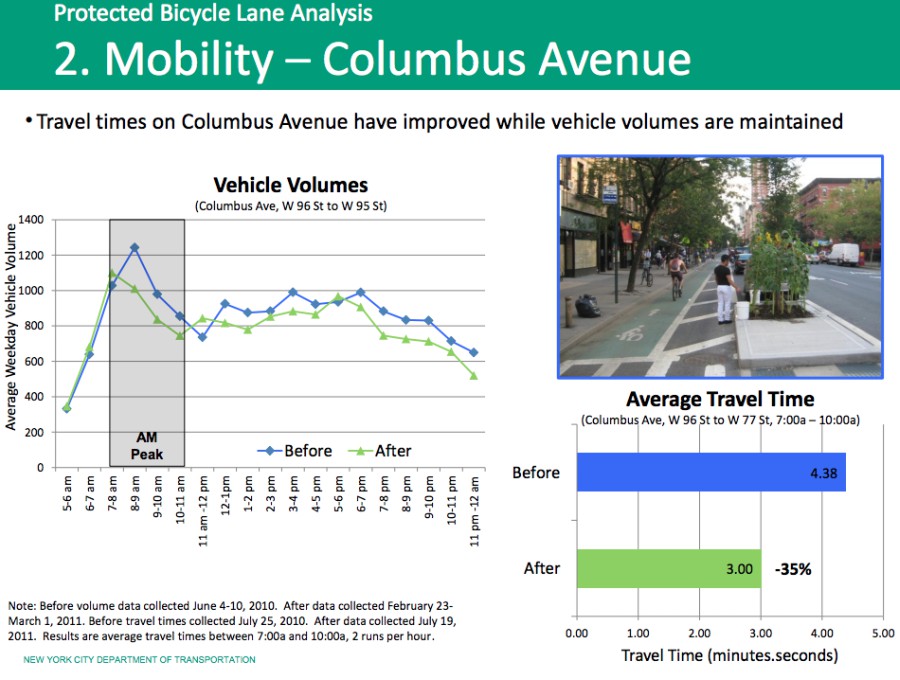

A major traffic study released in 2014 — after New York had built more than 30 miles of protected bike lanes — found that auto travel speeds in the Central Business District, where several lanes were implemented, remained steady. Travel times even improved on two roads — Columbus Avenue and 8th Avenue, where auto lanes were narrowed to install bike lanes. On both streets, the creation of “pocket lanes,” or lanes built exclusively for cars turning left, helped to both separate bikers and cars and speed up the flow of traffic.

Also worth mentioning: total traffic-related injuries dropped by 20 percent (2017 saw an all-time low), streets that received a protected bicycle lane saw a greater increase in retail sales, street crossing distances were shortened, and 110 trees were built as part of the bike lane project.

These numbers point to a missed opportunity for Philly, where the commuter bike share population is second only to New York despite the lack of protected bike lanes. Some city officials continue to drag their feet when it comes to extending Philly’s protected bike lane network, effectively discouraging would-be bikers and adopting the sort of car-first mentality that plays a role in clogging our streets in the first place.

You don’t necessarily need an entire network of protected bike lanes to see how supporting a cycling-friendly mindset can alleviate traffic in a city. And a 2017 study conducted in Washington (one of the nation’s other most congested cities) determined that the availability of a bike-sharing program reduced traffic congestion within a neighborhood by upwards of 4 percent. Results also indicated that bike shares specifically help to reduce jams in highly congested areas (like Center City, for example).

“Interactions among bicycle infrastructure and other modes of transit are only going to become more relevant as Washington, D.C., and other cities expand their bike-sharing programs,” the D.C. study concluded.

What’s in Philly’s Way?

In February, Councilwoman Blackwell told Philadelphia Magazine that if she could have vetoed one piece of legislation, it would have been the Chestnut Street protected bike lane that she once approved.

“People feel different ways about it,” she said. “You’ve lost a driving lane; there are parking issues. It’s a big problem. But the bikers love it.”

Last month, Blackwell introduced a City Council bill that biking advocates say could drastically hinder bike lane expansion in Philadelphia. The measure would mandate that a City Council ordinance is required to build, upgrade or modify any bike lane that could potentially affect “the flow of traffic” in Philadelphia. Currently, City Council approval is needed only for bike lanes that would remove car or parking lanes, per a 2012 ordinance largely seen as a Councilmanic power grab.

Blackwell calls the Chestnut Street bike lane a “big problem.” And yet, since the lane was implemented, the median morning-commute delay that drivers experience along its 12-block length is less than three minutes, according to a Google traffic data analysis by the Bicycle Coalition. There is no recorded delay during other times of day.

Tell Council: Don’t Slow Down #VisionZero https://t.co/rZJhJNKxq8 pic.twitter.com/hTGlpgMiHY

— Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia (@bcgp) February 23, 2018

Cycling advocates like Sarah Clark Stuart, the Bicycle Coalition’s executive director, say the three-minute delay is well within what a 2015 traffic study predicted — and a small price to pay to prevent tragedy on the road with the highest crash rates per mile among all city streets. After all, while traffic congestion seems to drive the conversation around street planning in Philly, there’s an obvious (and necessary) advantage of protected bike lanes that officials simply cannot continue to put off: saving lives. Philly saw more traffic deaths per capita in 2015 than New York, Los Angeles, or Boston. After the particularly high-profile death of 24-year-old cyclist Emily Fredricks in November, bikers lined up along the Spruce Street bike lane where the tragedy occurred, holding hands and forming a human wall to protect the road’s bike lane. Despite pressure from biking advocates, officials have not announced plans to protect the Spruce and Pine street bike lanes — the busiest in the city.

From a multimodal perspective, the recent time increase for drivers on Chestnut Street (which could also be partially attributed to construction in the area) doesn’t necessarily represent an increase in overall congestion. The Bicycle Coalition measured a 63 percent increase in the number of cyclists using the bike lane, as well as notable changes in cyclists’ behavior, including significant decreases in sidewalk and wrong-way riding.

The evidence is clear: If Philly is sincere about reducing traffic congestion and improving safety, walkability and livability in its neighborhoods, officials need to up their game when it comes to protected bike lanes.

If Blackwell’s bill were to pass, a specialized maintenance crew like the one that Kenney has proposed would likely face far more time-consuming roadblocks. Despite its pledge for improved safety, the Kenney administration has not fully weighed in on Blackwell’s bill. In a statement, city spokesman Mike Dunn said mayor’s office “looks forward to further conversations with the Councilwoman about the proposal.”

Philly’s cyclists are waiting for officials to view bike infrastructure and improved public transit not as extraneous perks but as necessities placed on the same footing as cars and trucks. Over the past five years, biking in Philly has increased by 14 percent, according to the Bicycle Coalition. The organization recently found that, per hour, the average amount of bikers on streets with buffered bike lanes is more than triple the amount at intersections with no bike infrastructure, and more than double the amount where there is a standard bike lane.

City Council is now faced with two opportunities to move Philly forward. The first comes in the form of rejecting Blackwell’s bill. The second would require members to sign off on the mayor’s plans for a 13-member Vision Zero crew. Then, officials need to make serious headway on Philly’s meager 2.5 miles of protected bike lanes.

To fail to do so would only stall progress and further clog our crowded streets.