Whatever Happened to Generation X?

As they head into middle age, the “slacker” generation of Philadelphians — sandwiched between the never-say-die boomers and the all-about-us millennials — is feeling overlooked, overworked and overwhelmed. But their chill, pragmatic approach to life might be just what we need right now.

Clockwise from top left: Sony DES51 Sport Discman; satin Eagles jacket; Jellies; Cabbage Patch doll; Nintendo Entertainment System; “Fresh Prince” cap. Photography by Jonathan Pushnik

My dad thinks my brother and I worry too much. Or not too much, he clarifies, but just that we worry. A lot. About everything.

My father and I are on the phone one December afternoon, discussing life. I’m looking out the window of my office conference room into a gray Philadelphia day; he’s on his patio in Florida, watching golfers make their way down the fairway of hole number six (as apt as symbolism can be). I called to ask what life was like for him when he was my age, which is 38. Was he optimistic? What kept him up at night? Did he think about his future?

It’s been 33 years since my dad was 38, but his answer comes quickly: “Well, I didn’t really worry. I had a good job at a secure company. There was a big career ladder ahead of me. I got 18 promotions in my 28 years and never applied for one of them.” There’s more: a guaranteed pension, dependable benefits, stock options. Health care was a line item, not a news headline. He had a nice suburban house in New Jersey and two kids who went to the local public school. (He never asked himself if the school was good enough.) He worked a lot, but that wasn’t an issue; parental guilt hadn’t been invented yet. For a middle-aged white guy in the 1980s, life was pretty damn good.

Which is why, when my father says that my 44-year-old brother and I worry a lot, I know he’s not being critical. We rehash how much has changed in only three decades. A few things that 1984 Dad never had to consider: mass shootings, police shootings, ISIS, 401(k)s, social media trolls, GMOs, corporate malfeasance, education reform, melting ice caps, bullying, high-deductible plans, co-parenting, fake news. Of course, the ’80s and ’90s came with their own problems, but those were tempered by the economic security of the era and enemies who lived somewhere else. College was affordable. Families were a lot less stressed. There was no such thing as a 24-hour news cycle. I’m pretty sure that in 1984, when you asked someone in the elevator how his weekend was, he said “Good” instead of “Busy.”

As my brother and I head into middle age, I know we aren’t the only ones feeling anxious. When I talk to friends my age around Philly, I hear the same refrains again and again: We’re way too busy — busier than we remember our parents being at the same age. We’re financially stressed, even though most of us know we’re better off than many other people. Between our jobs and our kids and all the social media noise, we’re pulled in a thousand different directions every single day. Maybe most disconcerting: Just when we feel like we should be taking over the world, we have the vague sense that the world might be passing us by.

In many ways, this feeling of dislocation is typical of my generation. I’m on the tail end of Gen X, the group born between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s. We were the “whatever” teens, considered — at least in comparison to the shake-up-the-world boomers — lazy, disengaged, cynical eye-rollers who didn’t care much about much, especially adulting. Two of our generation-defining emblems: a song named “Loser” and a movie titled Slacker.

That’s partially why, collectively, no one’s ever thought much of us. The boomers have for the most part ignored us, treating us like hapless little kids. And when the millennials came along — a group just as large and self-obsessed and overly dramatic as their parents — we became the forgotten middle children. We weren’t the “me” or the “me, me, me” generation. We were more like the “meh” generation, stuck between two cohorts who never stop talking. Lately, our sense of invisibility has felt particularly acute in Philly, a town still run by people in their 50s and 60s — but being remade to suit the tastes of people in their 20s.

Which raises the question: Where does this leave Xer Philadelphians like me? Is our moment over before it’s even begun? Should we just do our jobs, raise our kids, and spend our spare time rewatching Melrose Place? The slacker in me thinks that might be just fine. And yet I keep coming back to something, a quiet but confident voice in my head: Maybe, just maybe, our understated generational traits — from the detachment of our youth to our grown-up pragmatism — are exactly what’s needed to untwist a world that’s gone completely haywire.

I get a text late one night from my friend Renee, 38. She asks about my story: “What are you writing about, again?” “Gen X,” I reply. “Aren’t we Gen X?” she asks, then quickly follows up: “Lol. Oh wait. I think we are Y. No?”

It’s hard to talk about the mind-set of my generation with my generation. Maybe that’s because there are fewer of us. According to one recent count, there are currently some 75 million baby boomers and 75 million millennials in America, compared with just 66 million Gen Xers (a number that’s actually been significantly boosted by immigration).

It was even harder to find a sociologist who wanted to talk about us. “I’m skeptical that one age group is culturally different from another,” says Dustin Kidd, a sociology professor at Temple. (In case you couldn’t guess, he’s 42.) He believes that race, ethnicity, geography, and other socioeconomic factors have more impact on your life than the year in which you were born. His point is valid: Individual circumstances are paramount, and in that sense, making group generalizations can be baseless. But it’s also true that the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s — when Xers were coming of age — were vastly different from the decades that came before and those that have come since. And our experiences in those years created the DNA for how Gen X responds to the world.

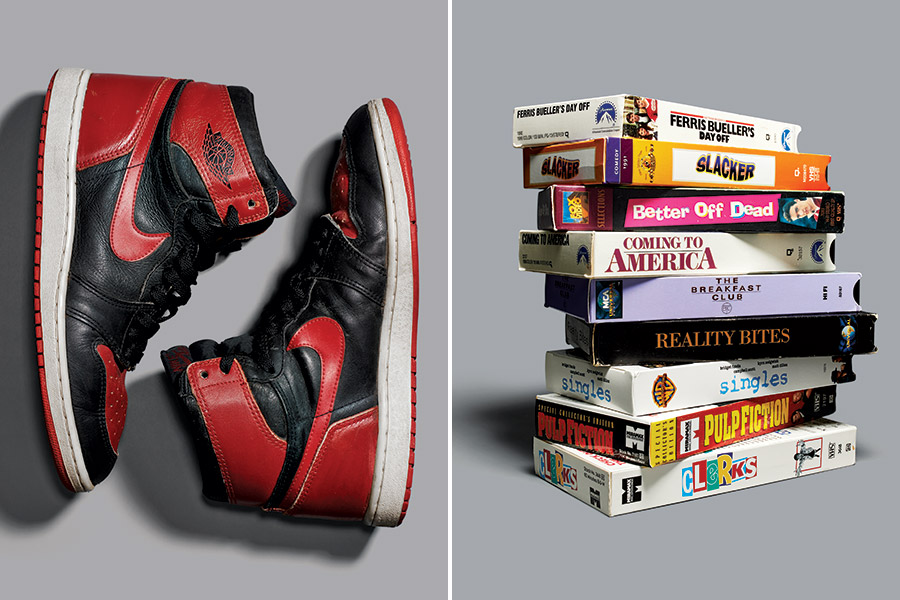

Left: Air Jordan 1 black/varsity red. Right: Collection of VHS tapes.

When Gen Xers were young, we were dubbed “latchkey” kids, because we often came home to empty houses. Whether it was for blue- or white-collar jobs, women continued to bust into the workforce, and divorce rates skyrocketed, hitting their peak in the 1980s — more than double what they had been two decades prior. These factors shifted the traditional family setup, and a whole group of kids was forced to be more independent. That freedom was bolstered by a sense of security; Etan Patz’s face didn’t appear on a milk carton until 1984. Our parents generally didn’t care how much Diet Coke we drank or how many hours of screen time we had. We were shooed out of the house and told to “be home before dark.” Sunblock — and, in my family, backseat seat belts — were optional. There weren’t too many expectations foisted on children then; parents led by example, not fear.

As Gen Xers became teens and young adults, we were deemed detached, uninspired and indifferent. (The term “Generation X” was popularized thanks to Douglas Coupland’s 1991 novel of the same name; “X” was meant in the math sense — an unknown variable.) We were cynical and rebellious, but not in a march-on-Washington, sexual-revolution sort of way. Our rebellion came in the form of skateboarding and black eyeliner.

But in time, something interesting happened: We mall rats, the group who snickered at the subversive irony of Beavis and Butt-Head and Wayne’s World, grew up into people no one expected us to be. In 1990, Time magazine ran a cover story lamenting the shiftlessness of the Gen Xers; seven years later, it reversed course with “Generation X Reconsidered,” admitting it had been wrong. Our new adjectives: hardworking, open-minded, pragmatic, inclusive, charitable. We weren’t big on labels. We still questioned authority, but in a respectful way.

The writers at Time weren’t the only ones who noticed. In 2001, when the first of our generation were entering our mid-30s, California sociologist and author Mike Males wrote that “ … Gen-Xers compensated for their boomer parents’ disarray by assuming more adult responsibilities at younger ages and refusing to emulate their elders’ excesses. Contrary to their detractors, Gen-Xer teens proved admirably competent in handling adult freedoms and duties.”

Admirably competent. Not a phrase that would do much for those high-self-esteem millennials. But we Xers take our compliments wherever we can.

It’s nice to be recognized for our strengths, but as my Gen X compatriots and I embrace middle age, we do so at a time when the world is being transformed economically, technologically and socially — basically, in all facets of life. And I’d argue that as we transition from a boomer world to a millennial one, it’s the Xers — those of us caught in between — who are most suffering the consequences of those changes.

Start with our financial state. Middle age is historically the “peak earning years,” but according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, male workers ages 35 to 54 currently make less than the same age group did decades ago. (There’s less disparity for women, but we still make less overall.) Why the gap? It might have something to do with, you guessed it, the boomers — specifically, their unwillingness, or perhaps inability, to step off the stage. “About one in seven Americans over 65 worked full-time last year, compared with one in 12 in 2000,” the New York Times wrote in a recent story about those in their early 50s headlined “Generation Grumpy.” “[Boomers are] also riding a wave of increasing dominance on the income scale and hanging onto high-paying work, keeping some of those slightly younger 45-to-54-year-olds from ascending to those jobs.”

The recession also had a major impact on us. According to a Pew Research report, Americans who are now ages 35 to 54 lost between 40 and 55 percent of their net worth in the economic downturn. This, of course, has implications when it comes to retirement: Thirty percent of Gen Xers have already tapped into their retirement savings, and most of us expect to work well beyond traditional retirement age.

Meanwhile, life has just gotten more expensive. Housing costs are up. The price of four-year public colleges has tripled since the 1970s. Child care can feel so out of reach that people decide to opt out, even though it’s not the most financially sound long-term decision. It should come as no surprise, I suppose, that almost 40 percent of Gen Xers say they don’t feel financially secure — and have more debt than savings.

As stressful as the state of our bank accounts might make us, our uncertainty about the future may be even more unsettling. Thanks to globalization and automation, the career ladder that my dad was dancing up like Paula Abdul is looking pretty damn rickety these days. Company loyalty feels like a liability, and job security is a thing of the past. Entire industries we chose to be trained for — hi, I’m a magazine editor — are disappearing. All of this, of course, is happening just at the moment when Gen Xers — who are stretched entirely too thin — need stability.

Middle-aged women seem to be hit particularly hard. Modern women carry more financial burden than ever before, which leads to serious time constraints in a society that’s become increasingly child-focused and appearance-oriented. Women across all income brackets and races feel like they’re never doing enough for their kids, their relationships or themselves. An Oprah magazine article in November dubbed this “the new midlife crisis” for women.

From left: CK One perfume; Motorola MicroTAC 650; Rollerblade.

Technology has only added to the confusion. Yes, my generation basically invented the modern Internet — Amazon, PayPal, Google and YouTube all came from Gen Xers — and we’re unquestionably more tech-savvy than our parents. But the majority of us weren’t building computers in our moms’ garages, and what we learned in our youth isn’t relevant anymore anyway. “In the ’90s and 2000s, everyone was learning how to make websites in high school,” says Kidd. “No one is paying for your HTML skills now.” Indeed, unlike the millennials, Gen Xers weren’t raised in a digital-first environment; social media is just one aspect of our busy lives, not the basis for a worldview. “I do feel like I’m getting to a place where my age is a liability,” says my friend Christy, a fellow writer and mom of two who lives in Fairmount. “I’m aware that I’m not an ingenue anymore, and I look at the talents that these kids have, the social media wisdom …” Christy, for the record, is all of 38.

Social media isn’t the only way we’re different from the large — and forceful — group that’s coming behind us. Millennials, for example, use words differently. I’m not talking about saying something is “lit” (whatever that means); I’m referring to a heightened sensitivity to everything that’s said or written. To an Xer like me, this desire to question the status quo is inspiring, but the millennial absoluteness is confusing. I don’t quite know how I feel about safe spaces on college campuses, where my lines are on sexual harassment, if statues should be removed. If you don’t have a very strong opinion these days, you can feel sidelined. Plus, Gen Xers like jokes, and it seems it’s not cool to be funny anymore.

So, yes, I say to my father: The struggle is real. And that’s why we worry.

You show up for dinner reservations on time, but the hostess explains there will be a short wait. You sit at the bar, have a few drinks, and try your hardest not to throw daggers at people who won’t get up even though they’ve already paid the bill. Why won’t they leave, already?

That’s what Philly feels a little like these days. “This town is literally run by older people and has so many millennials, and it feels like those are the only two perspectives that are ever considered, that are ever heard,” says Christy. “And guess what falls between the cracks? Things that middle-age people care about, like schools.”

City government neatly symbolizes what Christy is talking about. “Politics, and especially Philadelphia politics, have been pretty stagnant for a long time, in that there haven’t been a lot of younger people elected to office,” says Rebecca Rhynhart, who at age 43, without having run for anything in the past, was elected city controller in November. Rhynhart got dubbed a progressive early on, although she considers herself an independent voice. (So Gen X!) “It’s been business as usual for a long time, and there’s not been a focus on change or making things run more efficiently,” she tells me one recent morning. “I’m not saying every problem is easy, but there is a compromise to be made to move forward. If we had more leaders with that philosophy of ‘Let’s get it done,’ our government would work better, and people would have more faith in things.”

Rhynhart believes the tide is turning, though, noting that after her win, she got calls from contemporaries asking her how she did it. She also points to recently elected state reps in our age bracket — like Donna Bullock and Joanna McClinton — as leading the charge. “Gen Xers rising into political leadership will help bridge the divide between people and government — help bridge some of that apathy and dislike,” Rhynhart says. “We have a more modern approach.”

Being a bridge — not just between government and the people, but between the two large and idealistic generations that bookend us — may ultimately prove to be Gen X’s destiny. Boomers and millennials are both good at making everything very black-and-white. Idealism can be a powerful tool, but lately it’s turned everything from politics to the workplace into a never-ending, polarizing game of tennis. Gen Xers? We’re much more comfortable living in the gray. So yes, we do worry, like my dad says, but we aren’t afraid to get our hands dirty. And there’s great hope in our secret sauce of cynicism, humor, resiliency and tough love. We figure out how to move forward whatever comes our way.

Many of the Gen X bosses and business owners I talked to mentioned harnessing the energy of the millennials; they love their enthusiasm and fresh perspective, but they also make it clear there are rules and boundaries to adhere to. They all mentioned how they had to adapt their management styles to get the most out of their younger employees, but only did so up to a point (and not one of them bought a ping-pong table). “I think the boomers are more afraid of the millennials than we are,” says Christy. “We see and embrace the idealism, yes, but I like to think we are a marriage of the better parts of both generations.”

“There’s a better way to do things, a more pragmatic solution. It’s not rocket science,” says Rhynhart. “We need more inclusion, more diversity. I might view these as Gen X characteristics, and they are really all positive things.”

Unless I specifically ask them to, I’m assuming my friends won’t read this story. We aren’t really interested in ourselves. But just because we’re often overlooked doesn’t mean it’s all doom and gloom. While it’s most definitely not always fun, we do work tirelessly to find an optimistic version of balance. We spend time with our kids but also tend to ourselves (we popularized the phrase “date night”), and we aren’t self-obsessed. We have a better work-life balance than previous generations. “I do feel like sometimes I need to try harder to embrace the changing world, but it’s not part of my composition,” says Christy. “I should be more like a millennial, but that’s not who I am. I got to where I am by perseverance and a lot of really hard work for lots of years, and the same methods are going to get me to my next step.”

About that next step: It’s hard to know what the future looks like for us, but I have a few informed guesses. Our kids will live with us for longer, and we’ll have less money than we hoped, but that’s okay, because retirement doesn’t sound that appealing anyway. “I don’t really separate who I am personally from who I am at work,” says my brother. “But I haven’t had to, because this job is also my hobby. I like where I work, but I’ve made it that way.” We discuss how awesome it would be to retire to Florida. But then we laugh. It sounds nice, but what would we do there all day? We don’t golf. We don’t play bridge — or any games, for that matter. How many hours can one sit on the beach? “My hobby is drinking beer, which isn’t really a hobby,” he admits. “I have nothing tangible to replace working with.”

There’s other evidence that it’s our time to shine: Just go shopping. Versace’s latest runway show featured models from the ’90s, and toys like Cabbage Patch Kids, Ninja Turtles and Atari are back. On Walnut Street, there’s a Doc Martens store right next to a Vans shop, as if Kurt Cobain and Jeff Spicoli are standing together, letting us know that everything is going to be okay.

On a new special for Netflix, comedian Dave Chappelle, 44, even does a whole bit about my favorite ’80s Saturday-morning cartoon, the Care Bears. “They were like teddy bears, but they were people,” he explains. “They were all different colors … they all had different designs on their stomachs, and the designs told you something about what they were like inside.” He goes on: “And when shit got real bad … they didn’t get mean faces; they got determined. The leader would say, ‘Come on, guys, it’s time for the Care Bear Stare’ … and I’m not bullshitting you, actual love would shoot out of their chest and would dispel anything that was fucked up. And when we grew up, we wanted to be just like those bears.”

» See Also: Philly Is a Boomer Town (Still)

» See Also: Checking In on Generation X

Published in the February 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.