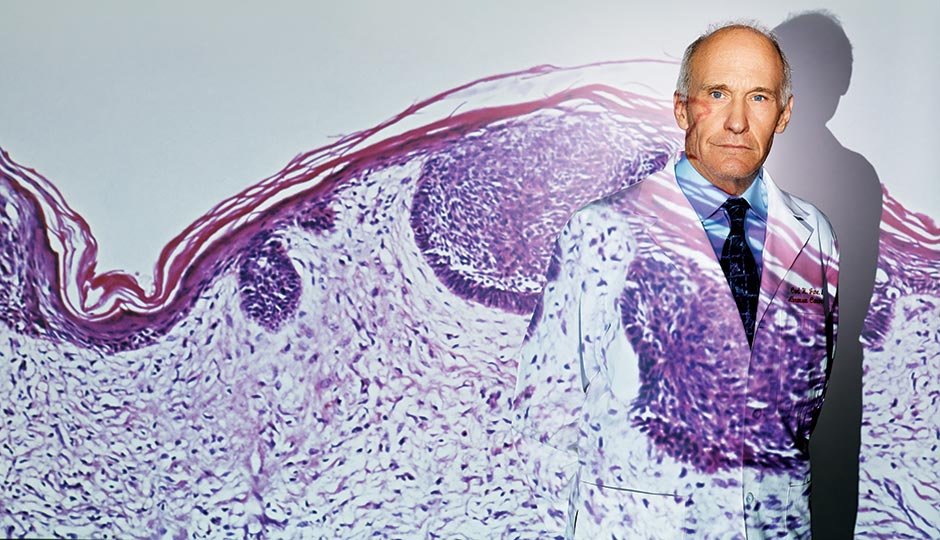

Carl June: The Cancer Slayer

Carl June | Photograph by Jonathan Pushnik

Take a giant leap toward a cure for cancer, and everybody wants a piece of you.

On an afternoon in late August, two days before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved his laboratory’s game-changing treatment for leukemia, Carl June was being patted with face makeup so he could look his best in a video being shot by the University of Pennsylvania, his employer. Nobody knew exactly when the FDA decision was coming, or whether it would be good news. But the video team had an hour of June’s time, and they wanted to get some footage ready.

“Didn’t we say no lab coat?” the video director asked politely as June sat down in front of a window overlooking the Philly skyline.

“I was just told ‘coat.’ But I don’t care,” the doctor said.

“Are you okay with that?”

“Sure,” June said, starting to remove the coat.

Pause.

“Do you usually wear your coat?”

He took off the coat.

The leukemia treatment that came out of June’s lab doesn’t involve a bone-marrow transplant. It consists of extracting a patient’s own white blood cells, genetically reprogramming them to attack the blood cancer, and putting them back to work as a sort of living medicine, on patrol inside the body for years. Clinical trials on some patients, many of them children, have obliterated their cancers, often after other treatments failed.

Carl June in his lab. Photograph courtesy of Penn Medicine

The FDA approval signals the dawn of a new era in medicine — it’s the first personalized cell therapy for cancer to be sanctioned in America. It also highlights June, at age 64, as a franchise player in the field, someone who can lead Penn and maybe Philadelphia to global preeminence in this emerging science.

And so Penn was making this video in part to inspire wealthy donors to write checks to the medical school. The marketing team wanted June to project about 80 percent scientific authority, 10 percent life-affirming wonder, and 10 percent pledge drive. He wasn’t uncomfortable or unfamiliar with the process. But he did have other things to get to.

“Do you have to be out of here at three sharp?” Penn’s video interviewer, Jill Wacker, asked June from off-camera.

“I think so,” he said. “It’s like back-to-back all day.”

June was in Philadelphia for about one week during August, in the midst of traveling around the world to give talks and help guide trials of his treatment. Off-camera, he was asked how busy his schedule had been lately, and everyone laughed. “I’m going to China tomorrow,” he said. (After that, Switzerland, France and Minneapolis. A pushpin-dotted map outside his office is labeled “Where in the World Is Carl June??”)

June was trained at Baylor College of Medicine after graduating from the Naval Academy. He was awed by the ferocity of the human immune system and began working on HIV in the ’80s, moving to Penn in 1999. Even without the lab coat, his angular face and cropped gray hair give him the look of a TV doctor out of central casting. That is, until you see him in spandex — he bikes to work at least once a week, eight miles each way from Merion Station. A rebellious sign on the wall in his office reads: “Bicycling: A Quiet Statement Against Oil Wars.”

June with, from left, his daughter Kristen, Amy Gutmann, Leonard and Madlyn Abramson, and June’s wife, Lisa, at an August “flash mob” at Penn’s Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine to celebrate the FDA approval. Photograph courtesy of Penn Medicine

Sometimes it takes a well-trained maverick to shake things up, says Richard Vague, the Philadelphia-based investor who was so enthralled by June’s work that he gave Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine $3 million to make June the Richard W. Vague Professor in Immunotherapy. In Philly, Vague works with tech start-ups and FringeArts, and he sees the same kind of outside-the-box spark in June. “These are all very creative people. These are not people who follow rules,” he says. “You don’t have to be a rebel to be creative, but in his case, the breakthrough was using the HIV virus to deliver altered DNA to the tumor. It’s hard to imagine a more bad-sounding idea.”

“Would you say this is a revolution in medicine?” the video interviewer asked June.

The doctor demurred. “I think others have already said that. I’m gonna wait to make that judgment.” Then, meeting halfway: “It has many of the features of a revolution.”

June is happy that more people will have access to the treatment. The government approval is for using doctored T-cells in children and young adults to address an aggressive type of leukemia — B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia — that may resist other treatments. Future approval is expected for older patients and, conceivably, for similar approaches to other cancers. The approval lets Novartis, which has licensing rights to the therapy, offer it commercially and makes it eligible to be covered by health insurance. Novartis gave it one of those weird drug-company names: Kymriah. And it announced a price tag: $475,000 per treatment course.

The sticker shock of advanced therapies like this will present a quandary for a while. Cell therapy can replace years of expensive treatments, and analysts suggest the price isn’t out of line. But insurance limitations may hinder access.

“I think it’s similar to when computers started,” June said. The first computers not so long ago cost millions. Today’s sub-$1,000 home computers outperform those early wonders.

June with Sanjay Gupta and Tom Hanks at the launch of Los Angeles’s Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy in April. Photograph courtesy of Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

An overhead shot of the August flash mob. Photograph courtesy of Penn Medicine

Of course, what people keep asking is how June feels about all this. He answers with stoic words like “gratifying.” Feelings are one place even globe-trotting doctors don’t like to go.

“He is a very emotional guy,” Vague says. “Back in the early days, you couldn’t hear him talk about the patients, their stories of kind of coming back from the abyss, without him tearing up.”

More often than not, though, feelings are kept out of the room. Vague tells the story of June receiving the Philadelphia Award in 2013. Unbeknownst to June, organizers had invited several middle-aged men the doctor had never met whose lives the immunotherapy treatment had saved in clinical trials years earlier.

“Carl didn’t know how to react,” Vague recalls. “The guys didn’t know how to react. They’re shuffling around. Staring at the floor. They didn’t know what to say.”

Originally published as part of “The 100 Most Influential People in Philadelphia” in the November 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine. See the entire list at phillymag.com/influential-philadelphians.