What the Hell Is Going On at the Pennsylvania Ballet?

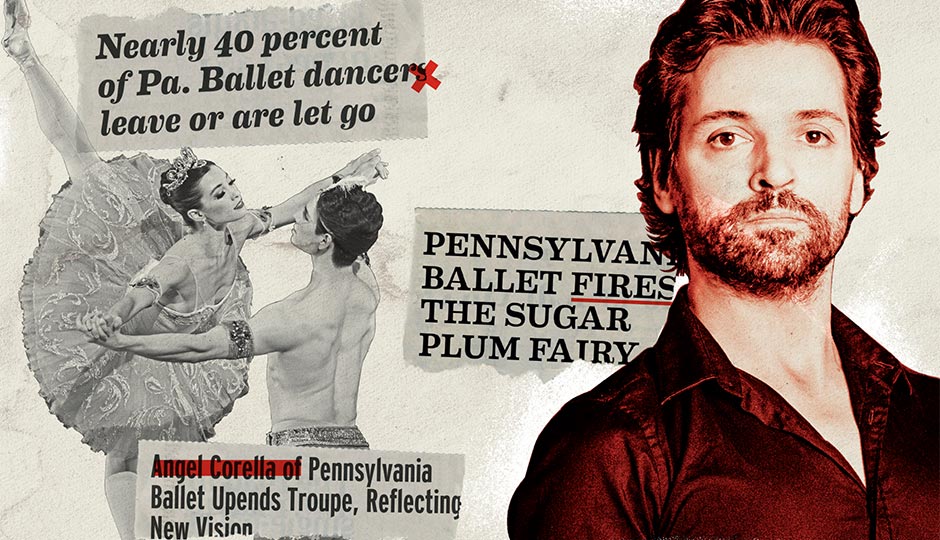

Corella, right, and Ballet dancers Lillian DiPiazza and Sterling Baca. Corella courtesy of Vikki Sloviter; Le Corsaire courtesy of Alexander Iziliaev

To judge by the headlines swirling around the Pennsylvania Ballet in recent years, the company has become a cross between Black Swan and The Hunger Games. News accounts didn’t seem to bode well for a smooth regime change following the July 2014 appointment of new artistic director Angel Corella: “Pennsylvania Ballet fires longtime artistic leaders, administrators” (August 2014). “Nearly 40 percent of Pa. Ballet dancers leave or are let go” (April 2016). “Angel Corella of Pennsylvania Ballet Upends Troupe, Reflecting New Vision” (April 2016). “Pennsylvania Ballet fires the Sugar Plum Fairy” (January 2017). “More staff members depart from Pennsylvania Ballet” (February 2017). “Pennsylvania Ballet leaders, husband and wife, are stepping down” (April 2017).

Corella, 41, left the American Ballet Theatre in 2012 after a 17-year career there in which he’d been one of the most celebrated dancers of his generation. The boyish-looking Spaniard’s electric charisma is a sharp contrast to his Pennsylvania Ballet predecessor. Tall, regal-looking Roy Kaiser had worked his way up through the ranks of the Ballet, avoiding the drama that’s often a hallmark of creative environments.

Corella brought a new panache and energy in keeping with the virtuosic style that marked his dancing at ABT. But the scale of change seemed daunting. And it aroused fears that the revered company, which kicks off its 54th season on October 12th with The Sleeping Beauty, might be deteriorating into chaos.

Turmoil is a constant threat in arts organizations today. They face rising production costs and pernicious financial challenges, considering the tempting on-screen entertainment that bombards potential ticket buyers every day. Yet live performance remains a draw. In fact, the qualities that define it — its ephemerality, its communal nature, the commitment and discipline required to make something marvelous happen in real time — are only gaining luster in contrast to our low-risk, predigested world. The challenge for the Ballet in such a world: to find a way to go on making its art.

The latest chapter in the Ballet’s story begins with the departure of its last artistic director. Roy Kaiser resigned in May of 2014, just as the company was winding down its celebratory 50th anniversary season. His move was shocking and … not shocking. Rumors had begun circulating in the dance community, and the company dancers were aware that his leave-taking was a possibility.

Kaiser, from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, had joined the company as a dancer back in 1979 and eventually rose to the top rank of principal dancer. His 1995 appointment as artistic director was the culmination of a period of Ballet turbulence marked by a parade of strong-willed artistic directors and near financial collapse — twice. Kaiser, the insider, provided the steady hand at the wheel the organization desperately needed.

“When Roy and his team came on, they brought a lot of stability to a company that had seen a lot of upheaval,” says Janis Goodman, former Pennsylvania Ballet board chair and current board member. “Roy and his team had grown up in the company, they danced in the company, and they stayed.”

But over time, confidence in Kaiser began to erode. Leading up to his 2014 departure, ticket sales had been flat for seven years, except in 2010, when the movie Black Swan spiked intense interest in dance. The troupe’s long-term debt was $3.3 million. Individual donor giving wasn’t where the board needed it to be — and neither was the board’s own generosity. Fund-raising to complete the company’s home on North Broad Street had stalled, leaving it only partially built.

In 2013, the then-board chair, Cary Levinson, and executive director, Michael Scolamiero, made a tactical decision: They engaged the services of consultant Michael Kaiser (no relation to Roy). Kaiser, known as the “Turnaround King” for his impressive record of rescuing sick arts organizations from certain death — the resuscitated included the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, American Ballet Theatre and London’s Royal Opera House — was charged with finding a path that would ensure the Pennsylvania Ballet a sustainable future. Putting his mantra of “Good art, well marketed” to work often requires overhauling an organization, and the Pennsylvania Ballet was no exception.

Michael Kaiser remembers the challenges he identified for the Ballet then: “The company is in the top tier of ballet companies in America. The problems it faced were not unusual ones. … It had real cash problems, but that’s not unusual. It wasn’t severe. I’d seen far worse.”

Kaiser’s final report to the board recommended creating “transformative” work as well as expanding the school and embracing diverse communities. He urged measures to “address [the Ballet’s] major administrative shortcomings: the need for a stronger board structure, the weakness of its marketing program and the need for a stronger focus on individual donors.” Kaiser is also a strong proponent of institutional marketing, which goes beyond publicizing specific programs to focus on promoting the company’s brand.

All of these steps are easier, of course, if you have a passionate leader who relishes the spotlight and connecting with the public as well as with private donors. But by 2013, the company wasn’t exactly the “It Girl” of the ballet world. Its reputation for reliable quality was intact, but the intangible spark of excitement that builds donor generosity, loyalty and buzz had dimmed after half a century.

And many dancers weren’t happy, either, according to Janis Goodman, who authored a report during this period, with fellow board member Michael Lillys, based on dancer interviews. The board hoped to pinpoint the source of behind-the-scenes discontent among some dancers.

“Frankly,” says Goodman, “the staff who had once lent stability when there hadn’t been any — well, there wasn’t any excitement anymore. There was not enough involvement with the growth of the dancers. What we realized was lacking was the hands-on, surefire technical brilliance of an artistic director and his team. … We needed fresh blood, fresh ideas.”

“I felt Roy might have been tired,” says Lillys, the current treasurer and finance and audit committee chair. “That’s a long time to run an artistic organization. The way the company evolved … it was time for a new artistic leader to give a renaissance to the company.”

A month after Roy Kaiser announced his resignation, he echoed the “fresh blood” sentiment at a City Institute Library talk he gave: “Ballet companies are living organisms,” he told the audience, “and you need new ideas. So I think it’s a win-win for everybody.” (Kaiser, now artistic director emeritus for the Ballet, didn’t respond to a request for comment by press time.)

Michael Kaiser led the global search for Roy Kaiser’s replacement. Thanks to his long reach into the international dance world, he was able to round up elite candidates, including Angel Corella. The two knew each other from Michael Kaiser’s time as executive director at American Ballet Theatre. “Michael is to me my fairy godfather,” says Corella, who had founded his own company (since shuttered) in Spain in 2008. “Is that how you say it? He supported me throughout my career.”

The Pennsylvania Ballet grabbed instantaneous attention with Corella’s hire. He came complete with an international network of ballet-world connections, a take- no-prisoners approach to executing his vision, and an ease with fund-raising. That was particularly important in a city with a limited donor pool — one in which arts organizations often fight for the same dollars.

“We needed what Angel gave us,” says Goodman. “Angel is an international star, and very hands-on. He’s always at rehear- sals. He strikes the perfect balance as an artistic director because he works well with people and is willing to go out on fund- raising calls. He dazzles people with his knowledge and excitement.”

But Corella’s arrival also marked the beginning of a makeover that started with the senior artistic leadership. Shortly after his arrival, ballet mistress Tamara Hadley, ballet master Jeffrey Gribler, head of the ballet school William DeGregory and Michael Sheridan, Roy Kaiser’s assistant, were let go. All had been dancers with the company — some from as far back as 1975. Their dismissal was an unmistakable signal that the new chief was more focused on the future than the past.

Corella says of the purge, “It was not reflective of who the team was and what they can do. It was more about the kind of team that I needed to create the new artistic vision.”

In his first year, Corella simply oversaw the programming Roy Kaiser had put in place for the 2014-’15 season. His artistic team began to come together. David Gray was hired as the new executive director. Gray’s wife, Kyra Nichols — the famous New York City ballerina and muse of the late, legendary choreographer George Balanchine — took up coaching duties with the company. Retired dancers Julie Diana and Zachary Hench took over from Hadley and Gribler as ballet mistress and master until 2015, when they relocated to Alaska. Samantha Dunster then assumed the task of rehearsing the dancers.

Retired New York City Ballet dancer Charles Askegard was added as ballet master in 2015. Nichols and Askegard aren’t just world-class talent; they brought with them the gloss of Balanchine and his tradition, reassuring local balletomanes who feared Corella might remake the company into a version of ABT, known for its classical style and evening-length story ballets.

But no sooner was the new team in place than it began to shift. This spring, David Gray and Kyra Nichols announced they were leaving for an opportunity Nichols couldn’t pass up, a position at Indiana University. The board is currently conducting a search for a new executive director.

In the Ballet’s executive offices this past summer, Corella springs from his chair, skirting the conference-room table to offer a hug — “I can’t help it,” he says in his lightly accented English. “I’m Spanish!” After adjusting the blinds for less sun, he outlines his progress toward his goals. The 2015-’16 season at last gave him the opportunity to create a slate of his own selections, and he served up a mixture of Balanchine and edgy choreographers — Justin Peck, Wayne McGregor, Liam Scarlett — as well as his own lavish restaging of the full-length classic Don Quixote.

But what was exciting for the ballet world came at a cost to company members. Corella made cuts deep into the roster in the spring of 2016 — the first chance he had to, under the dancers’ contracts. Until then, they’d benefited from a quirk created by Corella’s hiring date; instead of the typical one-year grace period before a new artistic director can make personnel changes, they got two seasons. In the final count, 18 of the company’s 43 dancers wouldn’t return — some by choice and some because they weren’t asked back. The press took note: EXODUS! NEARLY 40 PERCENT OF DANCERS GONE!

“Dancers have the right to go to the press,” says board member Janis Goodman, “but grow up. They had two [seasons] to prove themselves. The dancers shouldn’t be angry about Corella’s choices. They were suddenly under the guidance of someone hyper-engaged and involved, and they are expected to do what he wants.”

Asked whether Corella clearly articulated what he wanted from his dancers, one of those let go, 19-year veteran and former principal dancer Francis Veyette, says, “The [new] dancers he brought in made it clear. They were a different type of dancer. They were more classically trained — more than neoclassically trained.”

That difference touches on a concern voiced in the dance community following Corella’s appointment: that the Ballet’s identity as a “Balanchine-style” company might change under this new, classically oriented leader. Balanchine played a significant role in helping his protégée, Barbara Weisberger, found the company in 1963. She returned the favor by entrenching her mentor’s neoclassical style into the company’s DNA. Was Corella actively seeking to change that style and emphasize wow-inducing star turns? Some company dancers believed he was.

As Francis Veyette explains it, this difference simply comes down to stylistic preference. “To put it in football terms,” he says, “it’s like if you were the Eagles and you could either go with a ground-and-pound running game or a passing game with long bombs down the field. Neither one is better; they’re just different philosophies.

Veyette says the dancers tried to adapt to the new regime: “Everyone jumped in with both feet. We all loved the company and wanted to stay there and gave it our best shot. It’s the dancer’s responsibility to do what the artistic director wants you to do — it’s his prerogative — but at the end of the day, if you feel the artistic director is not seeking the type of artist you are, you have to find the company that is.”

Charles Askegard says, “Angel is very honest with the dancers. And sometimes those things are hard to hear, but at least you’re not left wondering why.”

Quite a few former PB dancers have found a new home at Miami City Ballet, another “Balanchine-style” company. They include Veyette, who teaches at its school; his wife, principal dancer Lauren Fadeley, who now dances in the company; and former principal dancer Arantxa Ochoa, who also now teaches there.

Whether Corella is shifting the company away from its heritage or not, a larger question hovers: Does it even matter? If the choice is “Change or die,” who cares if the dancing is different? It’s a classic “would you rather” moment: Ballet fans, would you rather have a different-looking company or no company at all?

For concerned traditionalists, Corella’s upcoming season has Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, Theme and Variations, and evening-length ballet Jewels. That’s a solid helping. Corella has often asserted his desire for chameleon-like dancers who can perform many styles. His individually approved dancers will need to prove their versatility in a repertoire that includes Balanchine, unconventional contemporary work, and sweeping classical ballets such as this season’s The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake.

“Dancing is a very short career,” says Corella. “As a dancer, either you’re at the company where you want to continue your career — or if not, you make the move right away, so you get to the company that will fulfill you artistically.”

Consultant Michael Kaiser gives this assessment of the PB situation: “It’s not unusual when a new artistic director takes over to have substantial turnover. That person has been hired to introduce a certain aesthetic and build exciting work. You can’t blame them for making changes to get there — although it needs to be done with sensitivity and with real care for those dancers who are displaced.”

Asked about the negative publicity, board chair David Hoffman says, via email: “One could say that any press is good press, but it did not feel that way to Angel and his team. I think some of the press came because the company had been stable for so long. Change can be disturbing, but without it, we die. All the radical change is behind us, and the company is shining.”

That change reflects the board’s faith in Corella’s vision and his will to get that vision onstage quickly — even at the risk of bruising some of the dancers’ egos or building a reputation as an insensitive manager.

“I empathize with the dancers who were here before and didn’t get contracts,” says Michael Lillys. “It’s always going to be difficult from the dancers’ standpoint, but this is part of the business. Angel wants the best dancers, and that’s what we want him to do. It’s our fiduciary duty to make the company flourish.”

The board likes what it’s seeing so far. It has extended Corella’s contract into the 2021-’22 season. Ticket revenue for last season was up 15 percent over 2013-’14. There’s been a 33 percent increase in contributed revenue from the board since Corella arrived. Individual giving is up 42 percent, not including the board gifts. A New York Friends of Pennsylvania Ballet has formed, and the numbers are rising for the Ballet’s Young Friends contingent.

Corella talks proudly about newly hired dancers who have won major dance competitions and have chosen to join his company. He loves the raw energy on display in the men’s studio classes and the abandon with which the dancers move onstage.

“We are trying to make the dancers understand that when the curtain goes up, they have to blow away every single person in the audience,” he says. “I go backstage before the show and I say, ‘Go for it. Don’t hold anything back!’”

Published as “The Turning Point” in the October 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.