11 Things You Might Not Know About Samuel Upham

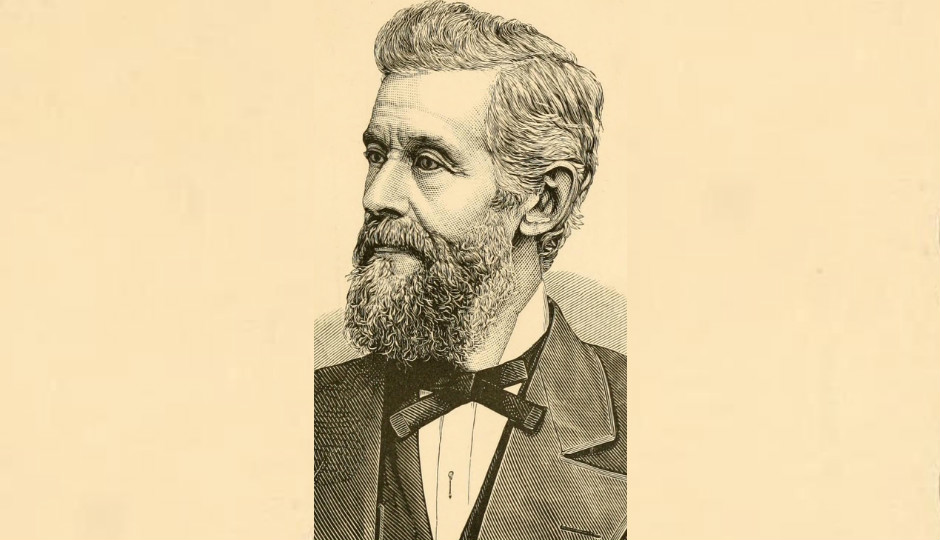

Image via Internet Archive Book Images

1. In late February of 1862, a year into the Civil War, a Philadelphia stationer named Samuel Curtis Upham observed a run on the sale of copies of the Philadelphia Inquirer at his shop on Chestnut Street. When he asked why, customers pointed out what was printed on the front page: a copy of a $5 Confederate bill. Philadelphians were curious to know what Confederate money looked like.

2. In a flash of brilliance, Upham realized there would be a market for souvenir copies of the currency. He rushed to the Inquirer’s offices and bought the electroplate that had been used to print the facsimile, then took it to a printer and had him run off 3,000 copies. He hung a sign in his shop promoting them as “Rebel notes,” on sale for a penny apiece. They sold out within days.

3. Upham then procured the electroplate for a Confederate $10 bill that had appeared in another newspaper and had a quantity printed. He was careful to append to the bottom of each a notation that read: “Fac-simile Confederate Note—Sold wholesale and retail by S.C. Upham 403 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia.”

4. Conveniently, when this note was cut away, what was left was an exact replica of a Confederate $10 bill. This fact didn’t escape the notice of Northerners who were engaged in illegally smuggling cotton from the South for fabric manufacture. They soon began to pay for their cotton with Upham’s counterfeit bills.

5. Upham advertised his bills throughout the North, promoting them in newspapers that included the New York Tribune and Harper’s Weekly as “mementos of the Rebellion.” His ads also offered to pay “three times the value in gold” for other denominations of real Confederate bills and coins for him to duplicate. By May of 1862, he had a dozen different Confederate notes and stamps for offer and claimed to have sold 80,000 in April alone. His success led to a price increase: Notes now went for five cents each. He also added a caution to his advertising: BEWARE OF BASE IMITATIONS.

6. About this time, rather mysteriously, the notes, which had hitherto been printed on letter stock, began to appear on fine-quality banknote paper. Some people claim that the U.S. Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, provided Upham with the paper after it was seized in a Union blockade. (Stanton is the man who, upon Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, famously declared, “Now he belongs to the ages.”) By summer, Upham’s counterfeits were superior in quality to the real thing.

7. But why would the Secretary of War want to help Upham make fake money? By now, his notes had spread throughout northern Virginia and as far as Arkansas, carried by Union soldiers who used them to purchase supplies. Cannily, the soldiers often offered the phony notes for purchases for which they were given real money as change. On May 31, 1862, the Richmond, Virginia Daily Dispatch published an outraged article decrying “Yankee rascality,” denouncing Upham as “a knave swindler of the most depraved and despicable sort,” and declaring that the phony notes were being spread “wherever an execrable Yankee soldier pollute the soil with his cloven hoof.”

8. Upham’s counterfeit notes were so ubiquitous that in August, Confederate president Jefferson Davis discussed them with the Confederate Congress, and the Confederate Treasury Secretary issued a report on Upham’s handiwork to the House of Representatives. The Dispatch warned that there was no way of knowing how many of the false notes had been circulated, but they’d turned up in Augusta and Savannah, Georgia, and Montgomery, Alabama.

9. While the Union government didn’t applaud Upham’s work openly, it didn’t exactly denounce him, either. When investigated by government agents, he pointed out that he never made copies of Union currency. (The investigation was eventually referred to Stanton, who dismissed it.) And while it would have been illegal for Upham to counterfeit another nation’s banknotes, the Union never recognized the Confederate States of America, so Upham’s money couldn’t legally be considered counterfeit. President Davis had no patience with such quibbling and put a bounty of $10,000 on Upham’s head.

10. One historian has estimated that Upham was responsible for between one percent and 2.5 percent of all Confederate currency in circulation while he was actively copying bills. Upham himself would later estimate that he had made and sold $15 million in phonies. By August 1863, inflation in the South was rampant, and its finances were so out of whack that no one would accept Confederate notes, real or fake; the cotton traders would only allow payment in gold or Union greenbacks. Upham had been so successful that he put himself out of business.

11. In the wake of the war, Upham boasted that a Southern senator had told the Confederate Congress that his efforts had “done more to injure the Confederate cause than General McClellan and his army.” He went back to selling stationery and cosmetics, including Upham’s Hair Dye, “best in the world,” and died of stomach cancer in 1885. Today, his counterfeits are rare and are collected … as souvenirs.

Follow @SandyHingston on Twitter.