Ralph Natale and the Decline of the Philly Mob

Book photo by IStockphoto

Ralph Natale was all of 12 when he first felt a dark, primal urge inside him — the desire to kill another man. On that occasion, the guy on Natale’s bad side was his father, Michael, who ran numbers for the mob.

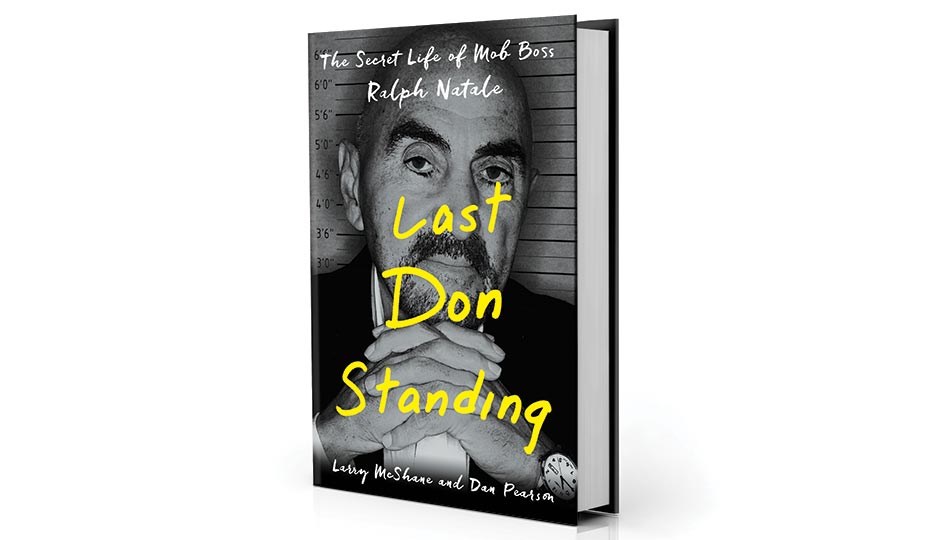

Michael had decided to punish his boy for missing a curfew by kicking him. “If I had something in my hands, I would have killed him. That’s when I knew what I was,” Natale, the former head of the Philly mob, recalls in the new book Last Don Standing: The Secret Life of Mob Boss Ralph Natale (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press).

Jarring admissions like that one are sprinkled throughout the book like locatelli cheese atop a plate of spaghetti. Co-authors Larry McShane, a veteran New York Daily News reporter, and Dan Pearson, executive producer of the Discovery Channel’s I Married a Mobster, offer a recap of Natale’s evolution from a tough South Philly kid to a cold-blooded killer who had a major hand in ensuring that crime families in New York, Chicago and Philadelphia all profited handsomely when casinos began sprouting in Atlantic City in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

The book also offers a dual portrait of the dramatic decline of the Philly mob, beginning with the 1980 murder of Natale’s longtime mentor, Angelo “The Docile Don” Bruno, at the hands of conniving underlings. The years that followed were marked by constant infighting, backstabbing and bloodshed that left the local La Cosa Nostra a mere shadow of its former self.

McShane and Pearson wrestle with a larger question of whether there can be any good guys in the world of organized crime. Natale often describes himself and some of the Mafia of his generation as honorable, stand-up men who lived by a code of loyalty and respect, while the generation that succeeded them is portrayed as greedy and recklessly violent. It’s hard to reconcile that with Natale’s reaction to overhearing an ex-con named George Feeney talking shit about Natale and Bruno: “I put three in Feeney’s face — boom, boom, boom! Right in his fucking dome. Done.”

Part of what makes Natale’s mob story unique is that he’s missing from it for long stretches. He spent 16 years behind bars on drug trafficking and arson charges, then took over the Philly mob after being released on parole in 1994. But his time on the throne was brief; he was scooped up on a parole violation four years later and soon indicted for financing a son-in-law’s meth operation. Natale had been the poster boy for omertà, the Mafia’s code of silence, but he opted to become a cooperating witness after learning that his underboss, Joey Merlino, had reneged on a promise to take care of his family after he returned to prison. (Natale has been in witness protection since his May 2011 release.)

Pearson is producing a biopic about Natale’s life, and there are plenty of interesting anecdotes to mine, including some concerning Natale’s quasi-friendship with infamous Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa and the mob’s role in allegedly getting Sonny Liston to throw both of his heavyweight bouts with Muhammad Ali. And then, of course, there’s the violence. “I never take pleasure in killing anybody,” Natale explains at one point in Last Don Standing. “I tell you, when it comes to that, I kill ’em so fast they don’t even know they’re dead. I shoot ’em. Right in the face.”