Philly to Crack Down on Use of Vacant Buildings in Wake of Oakland Tragedy

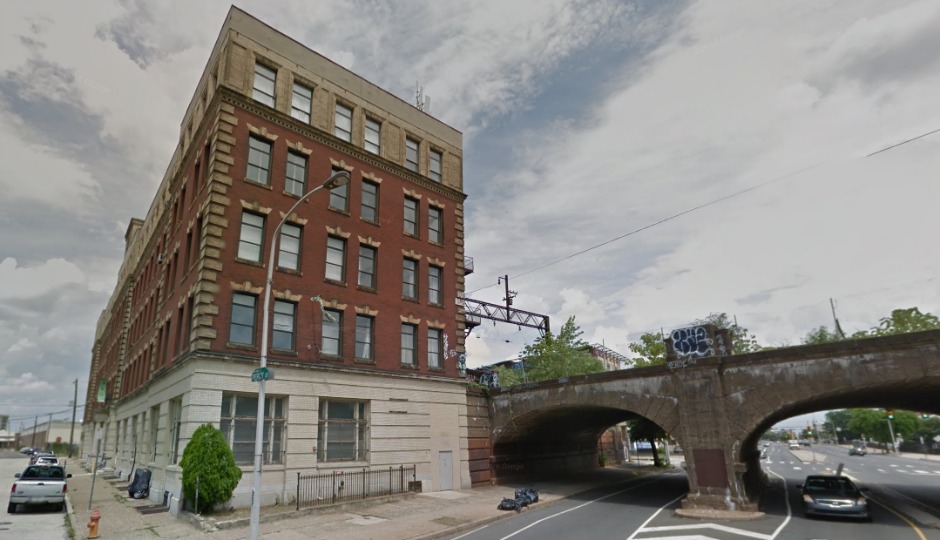

915 Spring Garden was home to more than 100 artist studios before L&I evicted the tenants in 2015, after a fire prompted the discovery of 29 code violations. | Courtesy Google Maps

Philadelphia officials are planning to crack down on illegal “pop-up” nightclubs and parties in vacant properties in the wake of a deadly fire that left 36 dead at a warehouse-turned-art-colony in Oakland last week.

Mayor Jim Kenney is working with the Department of Licenses and Inspections to seek out buildings with hazardous violations — especially if there’s reason to believe the buildings are being transformed into illegal gathering spaces.

Last week’s tragic fire engulfed a building known as the “Ghost Ship,” once home to many vagabond artists who couldn’t afford to pay rent in the neighborhood. The building had no permit for residences or performances, and its wooden infrastructure, boarded-up exits, and heaps of new and old materials made it a “death trap,” according to one former tenant.

It’s a grim situation that could easily have happened in Philadelphia, home to roughly 25,000 vacant buildings and 330 “imminently dangerous” building violations, on top of about 5,000 “unsafe” building violations. Karen Guss, a spokesperson for L&I, said officials are particularly concerned about “pop-up nightclubs” held illegally (without a specially assembly occupancy license) in Philly’s vacant buildings.

Guss said that in the last three years, L&I has uncovered about eight buildings that were converted into “some sort of studio or party space.” L&I is “pretty aggressive” in targeting such buildings, Guss said, because “even though there is a pretty low incidence of things going on, when they do, it can be so catastrophic.”

NewsWorks reports that Mayor Kenney said it’s up to the public to turn down invitations to gatherings in potentially dangerous buildings, “stay vigilant in their neighborhoods,” and “if you see this kind of ad hoc nightclub thing set up, to let us know as soon as possible.” But targeting one party here or there doesn’t necessarily get to the root of the problem.

Philadelphia abounds with vacant, aging, and often tax-delinquent properties that prompt far too many life-threatening warehouse and building collapses. This includes one notorious incident: in 2012, after two firefighters were killed in a fire at the vacant Thomas Buck hosiery factory in Kensington, the city revealed that the building had multiple code violations, and locals had long complained that squatters and vagrants would sometimes enter the factory.

L&I has since begun partnering with the Fire Department to more vigorously inspect buildings – especially large commercial ones. In 2015, the department evicted occupants at 915 Spring Garden Street after a small fire prompted officials to discover 29 code violations, including blocked exits and damaged elevator shafts and fire escapes. The old Reading Railroad building had been home to about 100 artist studios for more than three decades. Steven Donegan, an artist who had managed the building, said at the time that L&I had regularly inspected the building over the years but never issued a citation or noted a violation, according to the Inquirer.

“They had been there a long time without a problem,” Guss said. “Thank God nothing happened.”

The discovery came months after L&I announced that it had received $5.5 million in funding and would make room for 43 new building inspectors, on the heels of report by then-Mayor Michael Nutter‘s special independent advisory committee, which “found that L&I was underfunded, had too many responsibilities” and needed drastic restructuring, according the Inquirer.

At the time, officials said they would work to remove buildings that posed significant safety threats. Guss said the department hasn’t kept official data regarding how many properties have been demolished since then, but she said many buildings in the city are being “monitored,” and some are often fenced in to prevent trespassers from entering the property.

L&I tears down about 500 vacant buildings a year, Guss said, but the majority of those buildings are residential houses. Larger, commercial properties – like warehouses – are demolished less often, because they can be expensive to take down.

“Unfortunately, there are a lot of properties in the city that we just monitor because we can’t demolish them all,” Guss said. “We don’t have the budget capacity in terms of being able to hire enough certified demolition contractors.”

Follow @ClaireSasko on Twitter.