11 Things You Might Not Know About Legionnaires’ Disease

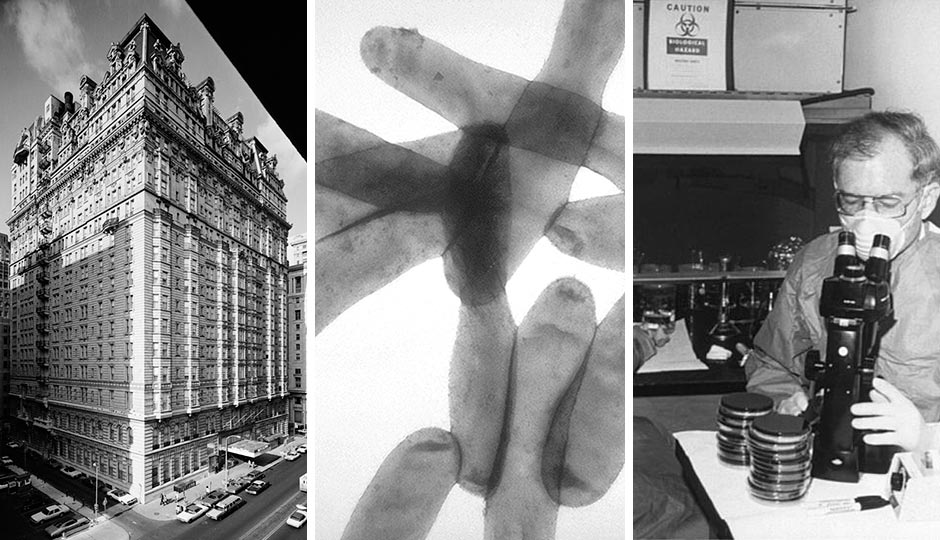

From left, The Bellevue-Stratford; pneumophila, responsible for over 90% of Legionnaires’ disease cases; Jim Feeley, examining culture plates upon which the first environmental isolates of Legionella pneumophils had been grown. All public domain.

In an eerie instance of metaphor fulfillment, this week’s Republican National Convention in Cleveland was hit with an outbreak of norovirus. Norovirus is bad, but it’s not the worst plague that can strike a convention. On July 21, 1976, in the midst of the city’s excitement over America’s Bicentennial that summer, 4,000 members of the Pennsylvania American Legion, a prominent veterans’ group, gather at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel at Broad and Walnut for their annual convention. Within a few days, hundreds of them would become sick with a mysterious illness; 29 would die of the ailment, which became known as Legionnaires’ disease. Here, a few things you might not know about the epidemic and its aftermath.

- The Bellevue-Stratford, opened in 1904 when Prussian immigrant George C. Boldt combined two smaller hotels (the Bellevue and the Stratford) into one $8 million French Renaissance palace, was at one time considered the finest hotel in the nation, charging a hefty $3.50 to $6 per room, per night, compared to other hostelries’ $2. It had 1,090 rooms and a staff of 700, including caretakers in the rooftop “pet hotel.” It hosted the city’s most glittering events and balls — there were two house orchestras, and the light fixtures in the Grand Ballroom were designed by Thomas Alva Edison. But by the time of the Bicentennial, the hotel was in considerable decline.

- Every U.S. president since Teddy Roosevelt stayed at the Bellevue. So did Bob Hope, Jimmy Durante, J.P. Morgan, Katharine Hepburn and a host of other famous folk. The hotel was the headquarters for the 1936 and 1948 Republican National Conventions and the 1948 Democratic National Convention.

- The day after the American Legion convention began, a few attendees developed cold-like symptoms: fever, coughing, chest pain, difficulty breathing. On July 27th, after attendees had returned home, the first death occurred — Ray Brennan, an Air Force veteran from Towanda, Pennsylvania, near the New York border. On July 30th, four Legionnaires died. By early August, there had been 18 deaths. The first person to realize they were linked was a doctor in Bloomsburg who had three patients with the same symptoms who’d attended the convention together.

- An army of medical examiners from the Centers for Disease Control descended on the Bellevue, along with state investigators. Since no known cause for the illness could be found, wild theories naturally developed: that the disease was due to biochemical warfare; that it was a CIA experiment of some sort; that it was an outbreak of swine flu, which earlier that year had broken out at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Helping to drive these theories were cases of the illness in people who hadn’t attended the convention but had been to or close to the hotel: a bus driver who’d delivered a drum and bugle corps to the city for a parade, a truck driver who’d delivered food. A hot line set up by the city took as many as 400 panicked calls an hour.

- State officials set up a “war room” with a map covered with red pins for deaths and yellow pins for reported cases. Workers canvassed hospitals by phone, searching for additional victims. Physicians, biologists and chemists worked around the clock to isolate and identify the disease agent. Epidemiologists interviewed every one of the sick Legionnaires and the families and friends of the dead, searching for a common set of experiences among them. The scientists were able to rule out swine flu or any other kind of influenza as a cause.

- One other possibility was ornithosis, a disease transmitted through bird droppings. A doctor in Allentown who suspected ornithosis treated three patients with the antibiotic tetracycline, and all improved. But CDC researchers ruled out bird-carried viruses along with bubonic plague, fungus, rabbit fever, Lassa fever, Marburg disease and typhoid fever. An August 16th, 1976, article in Time magazine, headlined “The Philadelphia Killer,” quoted the CDC director, David Sencer, as saying, “There’s an outside chance we may never find out the cause. … It may be a sporadic, a onetime appearance.”

- After six months, a CDC laboratory scientist, Joseph McCade, was able to isolate the bacterium that caused the disease, which he named Legionella pneumophila. Because of the time lapse, scientists were never able to pinpoint its source in the hotel, but they theorized that it had spread through the air-conditioning system. In April 1977, the CDC officially named the illness Legionnaires’ disease.

- The bacteria that cause Legionnaires’ disease grow best in warm water, in sites like hot tubs, cooling towers, grocery-store misters, hot-water tanks and public fountains. (They don’t appear to grow in car or window air conditioners, according to the CDC.) People inhale the bacteria when they inhale misted water or vapor. The disease doesn’t appear to be contagious from person to person, like the flu. It’s fatal in about one in 10 cases. Most at risk are those age 50 or older who are smokers or former smokers and/or have chronic lung disease or weakened immune systems.

- CDC scientists searching for similar outbreaks in the past identified a number of them: one at a Hormel meatpacking plant in Austin, Minnesota, in 1957 that sickened 78 workers; one in 1965 at St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital in Washington, D.C., that struck 81 patients, 14 of whom died; the relatively mild “Pontiac Fever” that sickened 144 visitors and staff at the Pontiac, Michigan, health department in 1968.

- Internationally, scientists have identified outbreaks of Legionnaires’ in Stafford, England (1985); at a flower show in the Netherlands in 1999 (318 sickened; 32 dead); and in Spain (the largest ever, in 2001, with 800 cases), Norway, Portugal and Toronto, Canada. In the U.S., some 5,000 cases are identified each year. Most are linked to contaminated water systems. There have been recurrent outbreaks in the South Bronx, including one last year that sickened 113 people and killed 12.

- The Bellevue shut down in 1976 amid the rash of bad publicity linked to the outbreak. In 1979, it was reopened by Ron Rubin, who’d bought it the previous year for $8.2 million and renovated it for $35 million. A second renovation in the late 1980s cost $100 million and resulted in retail businesses, offices and 172 total rooms. Following several more ownership changes, the hotel is now officially named the Hyatt at the Bellevue. More colloquially known as the Grande Dame of Broad Street, it’s on the U.S. Register of Historic Buildings.

Follow @SandyHingston on Twitter.