10 Things You Might Not Know About Beer in Philly

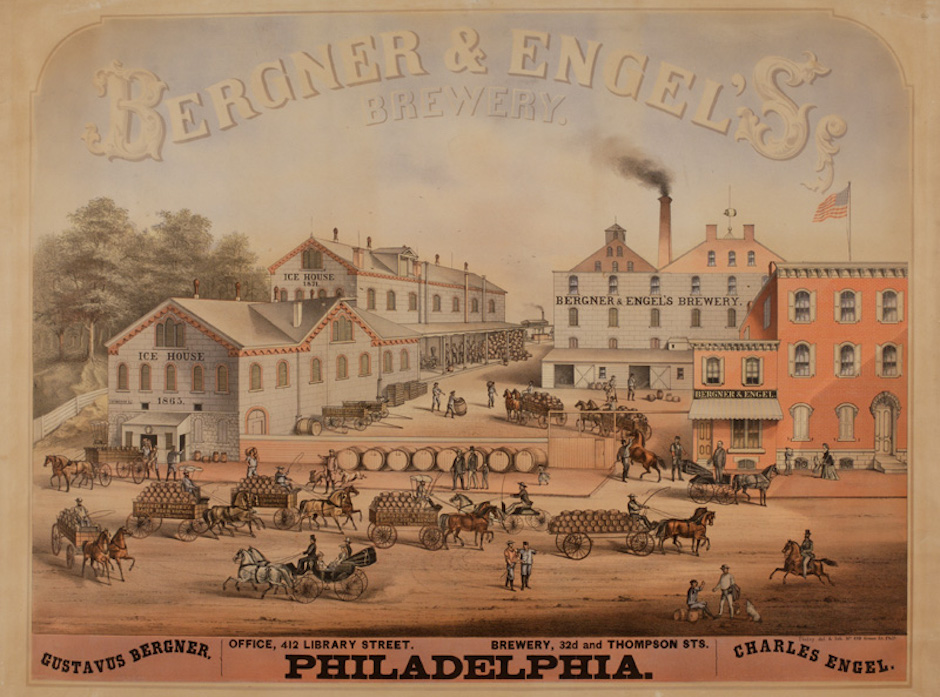

Bergner & Engel’s Brewery via the Library Company of Philadelphia

Beer is big in Philly right now, but it’s not as big as it once was. “I drink no cider,” John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail back in Boston during the run-up to the Revolution, “but feast on Philadelphia beer.” Rich Wagner’s 2012 book Philadelphia Beer: A Heady History of Brewing in the Cradle of Liberty overflows with tales of the city’s brewers, breweries and drinkers. Beer Week kicks off this week. Here, in celebration, are a few of the facts Wagner’s book contains.

- Beer was as much a food as a beverage for the earliest Philadelphians. William Penn reported that most beer brewed here late in the 17th century was homemade from molasses infused with pine or sassafras, the latter of which is now banned by the FDA because it causes cancer. (Sassafras oil contains a chemical used in the manufacture of the drugs MDA and MDMA.) The wealthy brewed their beer with malt. As of 1685, Penn was able to report that a brewer was now providing beer in the city.

- That brewer was William Frampton, a New York merchant said to have transported the first cargo of slaves to Philadelphia. He built his brewery, plus a bake house and tavern, at the southwest corner of Front and Walnut streets. After his death in 1686, the business continued under other owners through 1709.

- At the September 1787 Constitution Day celebration commemorating Pennsylvania’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution, the parade included 10 brewers wearing stalks of barley in their hats and carrying hops poles, malt shovels and mashing oars. They also bore a banner with the motto “Home brewed is best.”

- The neighborhood that became known as Brewerytown offered a number of water sources for beer-making and was close to the Schuylkill River, which provided ice for refrigeration in underground cellars or icehouses. The first such icehouse was built in the 1840s and held a thousand barrels. Settled largely by German immigrants, Brewerytown was providing half the city’s beer by 1900.

- The Philly brewery house of Bergner & Engel won two medals at the 1876 Centennial, for its draught and lager beer, as well as the grand prize for its lager at the Paris Exhibition in 1878, the Grand Gold Medal and Diploma of Honor in Brussels in 1888 and Paris in 1889, four medals at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, and the grand prize at the 1895 Amsterdam Exposition. The brewery was renowned for its Tannhauser Export light beer and Culmbacher dark beer, and its beers were sold throughout America and the world.

- One of Philly’s richest brewers was Louis Bergdoll, who built a brewhouse at 29th and Parrish streets in Logan Circle, alongside the Pennsylvania Railroad. After his death, his widow, Emma, became a major stockholder in the company. During World War I, her son, Grover, and stepson, Erwin, both dodged the draft. Grover’s evasion became a national news story, with reporters writing about sightings of “Ma Bergdoll’s boy.” He ran away to Germany and also managed to avoid the draft there. Grover’s son, Alfred, did his part by shirking military duty during World War II; an unpublished biography of his exploits was titled The Curse of the Bergdoll Gold.

- German immigrant and Civil War veteran Trupert Ortlieb opened a small brewery near 3rd Street and Germantown Avenue after the war, then bought another on 3rd Street south of Poplar. His beer proved highly popular, and he was succeeded as president of the company by his son, Henry T. Ortlieb, in 1893. Henry’s son, Henry F., took over a year later, and the brand, which had been called Victor Beer, began to be known as Ortlieb’s. By the time of Prohibition, Ortlieb’s was producing 30,000 barrels a year.

- By the turn of the century, small neighborhood brewery taprooms were becoming obsolete, as technological advances favored bigger brewers. Brewery workers were the highest-paid industrial laborers in the nation, and though Prohibition loomed on the horizon, brewers thought their product would be exempt, since it wasn’t as strong as spirits. But in August 1917, Congress passed the 18th Amendment prohibiting the sale, transportation, importation or exportation of intoxicating liquors. All breweries were ordered to cease production as of December 1, 1918; the rationale was that the transportation and labor involved in brewing was needed for the war effort. City brewers assured the citizenry that they had a six-month reserve on hand.

- While some breweries closed in the wake of Prohibition, others produced “near beer” and injected it with alcohol while in the barrel; hid barrels in tunnels and behind false walls; repainted their trucks with the names of laundries and dairies; bribed inspectors and cops; and even went to court to fight for their right to make beer. In 1928, the venerable Bergner & Engel went bankrupt. The city’s biggest brewer had been made an example, with 900,000 gallons of beer poured into the sewers.

- With the dawn of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt asked Congress to again legalize beer and liquor so the government could collect tax revenue. BEER IS COMING BACK read a sign erected atop the Poth brewery in Brewerytown. On April 6th, 1933, all Philadelphia police were ordered to report for duty at 10 p.m.; beer sales were slated to start at midnight. Though the heavens opened and rain poured and lightning flashed, thousands of people turned out to celebrate — and drink. After all, they’d waited 13 years. Even so, this is Philly, so there were complaints that the midnight beer was warm.

Follow @SandyHingston on Twitter.