10 Things You Might Not Know About the 1876 Centennial Exhibition

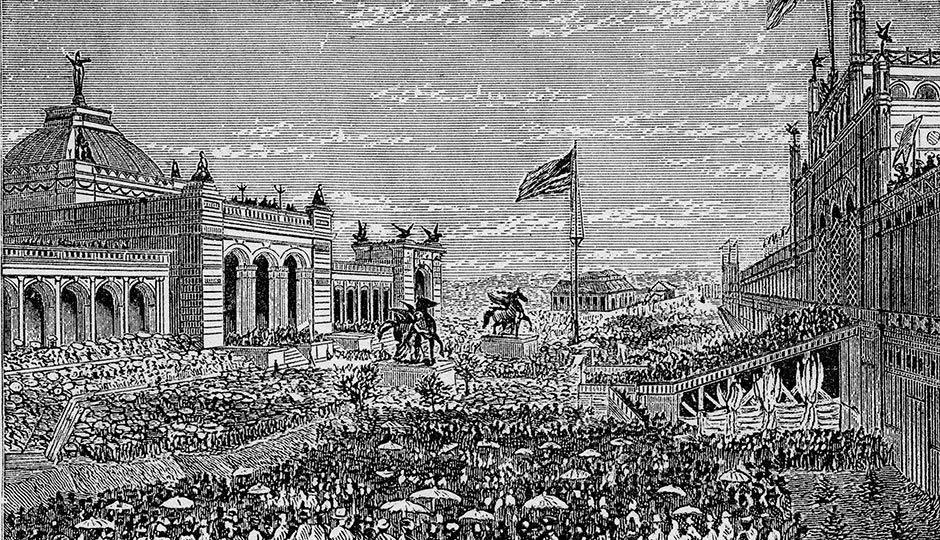

By James D. McCabe from “The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exposition Held In Commemoration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of American Independence.” Public domain from The Cooper Collections of U.S. History.

Today marks the 140th anniversary of the opening of the 1876 Centennial Exposition, which brought nearly 10 million visitors — almost a fifth of the nation’s population — to Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park to view what were then the Wonders of the World. This great World’s Fair — the official title was “The 1876 International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine” — was the first ever held in the United States. It introduced attendees to a host of new technological inventions and some really tasty foods, and forever changed the landscape of the city. Decisions made by the Centennial Committee as to roads, buildings, gardens and vistas continue to reverberate today. Here are ten things you might not know about the greatest party this city ever held.

- On opening day, ceremonies began with the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry marching President and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant to their places in the grandstand, where they were joined by Emperor Dom Pedro II and Empress Teresa of Brazil, who were the first reigning monarchs ever to visit the United States. An orchestra regaled the crowd of 186,272 with the anthems of a dozen foreign nations, concluding with “Hail Columbia” and a “Centennial Inauguration March” composed by Richard Wagner. Following prayers and remarks, the President’s party processed to Machinery Hall, where Grant and Dom Pedro turned the master levers to start up the Corliss Duplex Engine, the largest steam engine in the world (it was 50 feet tall and powered the hundreds of machines in the building), symbolizing America’s industrial prominence.

- The floor plan of the Main Exhibition Building was patterned after Center City’s layout, with four squares surrounding a central square. Made of wood, iron and glass, it was the biggest building in the world, enclosing 21.5 acres (Rittenhouse Square, in comparison, comprises seven acres) and measuring 464 feet wide and 1,880 feet long. Indoor fountains served to cool the building off. Exhibits inside were related to mining, manufacturing, metallurgy, science and education. After the Centennial closed, the hall was auctioned off for $250,000.

- The Eastlake- or stick-style building on the fairgrounds where visitors procured their official catalogs was dismantled after the Centennial and moved to Wayne, then moved again to Strafford, where it still serves as the SEPTA train station.

- Outside the fairground gates, along what became Parkside Avenue, exhibits not deemed worthy or appropriate for the grounds themselves offered hotel rooms, cheap restaurants, ice cream and shows of can-can dancers in short skirts and bandeau tops, in makeshift wooden structures. Initially, sales of beer and wine were banned, but when attendance dropped during a summer heat wave, the Centennial commissioners relented.

- Among the culinary treasures first introduced and/or popularized at the Centennial were Hires Root Beer, Heinz ketchup, sugar popcorn, soda water and bananas.

- As for that “Manufactures” part of the official name, inventions introduced included Alexander Graham Bell‘s telephone (“My God, it talks!” Emperor Dom Pedro said as he held the receiver to his ear); the first Remington Typographic Machine (a.k.a. typewriter, complete with QWERTY keyboard); a five-foot-by-eight-foot hand-cranked mechanical calculator (it was rendered obsolete by smaller models within a decade); and a double-decker steam-driven monorail that ferried passengers 150 yards between Horticultural Hall and Agricultural Hall.

- But surely the highlight of the Centennial was the convertible portmanteau demonstrated by resourceful young Civil War veteran Ethelbert Watts, a graduate of Penn. A portmanteau, or suitcase, made of rubberized cloth, it could be fashioned into a bathtub, “to afford travelers in places where such conveniences are wanting the luxury or comfort of bodily ablution.” Watts was the great-grandfather of Downton Abbey actress Elizabeth McGovern.

- The women of Philadelphia had contributed greatly to the success of the Great Central Sanitary Fair that was held in Logan Square in 1864 and naturally expected to do the same for the Centennial, but were denied permission to show their exhibits in the Main Hall. Undaunted, and led by Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, great-granddaughter of Ben Franklin, they built their own exhibit space, the Women’s Pavilion, which promoted more than 80 patented inventions, all produced by women, intended to provide them with less housework and more leisure time. Among these were a dishwasher, a self-heating iron, a stove, a frame for lace curtains, emergency flares and interlocking bricks. Information was also provided on the dress reform movement, which aimed to liberate ladies from corsets and heavy Victorian dress.

- It originally appeared that the hugely successful Centennial Exhibition had turned a profit for its original investors. But in 1877 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that funds provided by Congress had only been a loan and had to be repaid. There wasn’t enough money left to dismantle or sell off all the buildings, but a group of the investors tried to keep the party going by creating the International Exhibition Company and purchasing the Main Building and its contents at auction, intending to continue to operate the facility. Alas, the building hadn’t been constructed with an eye to permanence, and it soon deteriorated. According to a new book by historian Elizabeth Milroy, The Grid and the River: Philadelphia’s Green Places 1682-1876 (Penn State Press), the Fairmount Park Commission soon ordered the IEC to vacate the building, charging that it had devolved from education to entertainment, with “prestidigitateurs, recitations, speeches, drills … billiard playing … fire-works, balloon ascensions [and a] grand fancy dress carnival on roller skates.”

- Hermann Schwarzmann, the young architect of the Centennial Exposition — the man who beat out famed park designers Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux for the design of Fairmount Park, who drained the land on which the Centennial stood, who built its railroad and bridges and designed most of its buildings — left Philadelphia not long after the fair gates closed in November 10, 1876. He moved to New York City, where he formed an architectural firm and achieved national renown before dying of syphilis in 1896, at age 46.

Follow @SandyHingston on Twitter.