How Penn Parties Now

Photography by Evan Robinson.

It takes three seconds for the champagne to spurt out once the bottle’s opened — four and a half if you’re lucky. Minutes before midnight, the foam will sop the flatiron-burned hair of girls in tight black dresses, splatter their dates’ Burberry ties. The floor — of a downtown club with bribable bouncers, a Center City ballroom, sometimes even the mansion of a frat on the University of Pennsylvania campus — will slicken and stick. The revelers are Penn students, some of legal drinking age, others not. They’ll roll their eyes, clutch their drinks, whisper to each other that the boy with greased-back hair showering the crowd with Dom Pérignon is such an idiot, God, who does that? But in those three seconds, the flash on Evan Robinson’s camera will go off 10 times.

The next morning, the champagne sprayer will lurch for his phone from his bed on campus. In Evan’s photo, he looks some kind of glorious — bulged eyes, lips open, king of a party he can’t completely recall. He’ll grin, change his profile picture. Think he had the time of his life.

When you’ve photographed more than a hundred of the Ivy League’s most lavish parties, they blend together, save for the time stamps. Twenty-three-year-old professional photographer Evan, a 2014 Penn grad who shot college bacchanals and professional commissions alike throughout his undergraduate career, still returns to campus every semester to capture the absurd, the debauched, the unapologetic frivolity characterizing Penn’s over-the-top nights out. And he’ll be the first to tell you — each one is more than just a party. For these kids, it’s an opportunity to forget, a chance to remember while you’re here. A rare moment to be no more and no less than 22 and seemingly invincible, shielding yourself from the blast of $200 champagne.

Photography by Evan Robinson.

The period between nine and 10:30 p.m. is a waiting game. The attendees are still pouring boxes of candy-pink wine into glasses at a downtown hot spot; maybe a fraternity’s social chair paces about or sips from a pocket flask, finally relaxed. Everything’s going to be okay now: The DJ showed up, the bouncer’s been paid off. Evan drinks a bourbon and walks around. This is his battleground for the next four hours.

Penn students pride themselves on their school’s reputation as “the social Ivy” — an image that’s evolved (or devolved, depending on your point of view) since the ’70s and ’80s, when parties were scarce and Smokey Joe’s was the only option for nightlife. In 2014, Playboy ranked Penn the number one party school in the nation; while most of campus still doubts that claim, the University City party season spans year-round, with only midterms and final exams as serious interruptions.

Unsurprisingly, there are different tracks to Penn’s social life. There are the pulsating, gloriously grimy open affairs — watercoolers full of jungle juice, wood floors and sweating walls, where the barriers to entry are the proper girl-to-guy ratio and some skillful name-drops to the frat boys who guard the door. There are the non-Greek house parties, makeshift bars on dorm-room desks, apartment complexes filled with counters of $7 bottles of Banker’s and plastic jugs of rum and Coke. And then, worlds and literal miles apart, there are the events Evan Robinson is commissioned to shoot: sorority formals at the Cescaphe Ballroom, a renowned wedding venue in Northern Liberties. Battleship Brunch, a once-a-semester booze-laden day party on the U.S.S. New Jersey. Gatsby-themed Greek date nights with champagne flutes and strings of pearls. The kinds of parties that only belong to a certain sector of Penn’s Greek life and social scene, a small but, thanks to social media, perpetually visible element of campus culture. These are events Evan wouldn’t have attended if he weren’t the photographer.

He almost wasn’t a photographer at all. Evan spent most of his childhood in Los Angeles as a sports kid and guitar player. But during a basketball game his junior year of high school, he felt a sharp pain in his hand and looked down. His pinky was sideways. He couldn’t touch a ball or guitar for 16 weeks.

The surgeon handed him a camera instead. Told him to play around with it.

Evan grins. “And it was fun.”

His accomplishments speak for themselves. He has photographed for the Wall Street Journal, the National Geographic Channel, Cosmopolitan. His first payday as a freshman marked a turning point, he says, as 5 a.m. drives to New York and flights to Los Angeles for photo gigs made classes almost an afterthought. That same year, an off-campus fraternity gave him a few hundred dollars to shoot Woodser, an annual rave in the Pennsylvania wilderness an hour’s bus ride away.

“And from there,” Evan says, “it was just a cascade.”

Word spread quickly about the guy students needed to hire to shoot their fetes. In the landscape of social one-upmanship, blurry iPhone pics were no match for a pro’s lens. The goal was to have proof: concrete evidence of fun had, drinks sipped, nights out that were bigger and better and brighter than anyone else’s. Evan now charges around $525 per gig. “When people pay more, they tend to respect your work more,” he says. “If you show up there for 100 bucks, you get shat on, but if you’re one of the most expensive parts of a party, they’re not going to fuck with you.”

Bonding with his subjects is made easier by the fact that Evan is still practically one of them. He’s also a participant in these boozy rituals, not just hired help.

“If you guys have an open bar with free champagne and bourbon, guess what? I should be able to grab something off the top shelf,” he says. “Otherwise, it’s too weird of a separation between me and them. If we’re going to get along and I’m going to have fun taking photos with you guys, then I need to have fun being here. And I’m not going to do that if I’m eating fucking ramen and sipping on a shitty Smirnoff cocktail.”

The first couple clatters into the restaurant, drunk and babbling, hair combed into black silk. If they know Evan — and many people at these parties do — he’ll get a high five or a hug. To some, he’s a fixture as important as the bottomless bubbly or zigzagging bass.

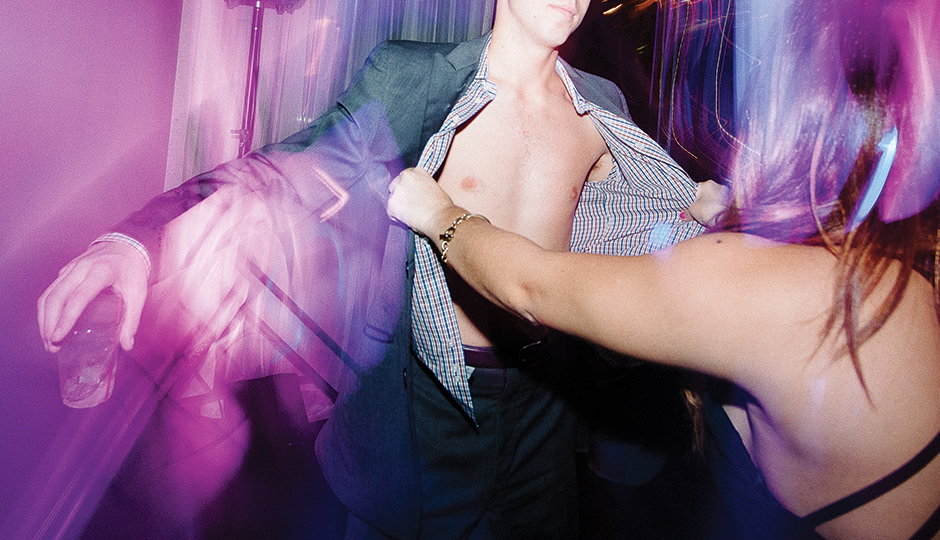

Evan’s photos are known on campus for, among other aspects, their “light streaks”: jets of colored light beams curled around an entwined couple or a cluster of grinning girls. Evan has to shake the camera to get the right angle for that effect, which gives the photos a more professional, polished look, another distinction from the smartphone Facebook albums anyone could upload.

There were tricks to building trust. He took advantage of his high tolerance and threw back shots with partygoers: “If you seem like that one friend who won’t drink at a party, like that awkward, sober piece of shit, they’re not going to let up around you.” He sparked conversations; he threaded the dance floor. He couldn’t just shoot for four hours straight. He had to engage.

The more parties he worked, the more Evan became a fixture. The people he photographs are usually delighted to see him, he notes. Of course they are. He’s the one who makes them look fabulous.

“People want him because he takes good pictures,” says Hannah Noyes, a Penn junior from New York City who’s attended events Evan has photographed. “And you definitely want, you know, something you can put as your profile picture. So it looks like you’re having fun.” She laughs, raises her eyebrows. “If you don’t have a good Insta picture, like, were you even there?”

At 10:30, that couple walks in, and Evan knows it. Not the first ones to arrive, but the ones who stroll in 40 minutes later, heads tall. The ones people turn around to see. They have the right little touch on the arm, the right lilt to their voices. They have something.

“You have to figure out who it is,” Evan says. “And then you have to get them to do it for 10 minutes more than they wanted to, with a few more people than they wanted. You have to make them feel special, because they make the people around them feel special and have this radiant effect where what could have become a mediocre party becomes this total raging mess of joy, and everybody is bobbing to this intoxicating metronome of beauty and excitement and hot bodies rubbing against each other and forgetting all the shit they do every day at an Ivy League like Penn. You’ve got to bring that out.” He nods to himself. “That’s your job.”

And the day-to-day at Penn can feel like a race to the night. The events Evan photographs mainly take place in a tight two-week span — fraternity and sorority formals are crunched into the period between Reading Days and final exams at the end of each semester. But every week at Penn, the same cycle unfolds: Thursday-night parties at clubs in Center City (known as “downtowns”), beer pong in sweat-slicked frat basements, wine-splashed dinners at BYO restaurants across the city. When Evan was a student, he didn’t stop shooting during Spring Fling, a weekend-long carnival headlined by a musical performer and known for its near-constant revelry.

“The way that I experienced Penn, it wasn’t competitive and it wasn’t cutthroat,” he says, in contrast to the popular perception of campus culture. “It was open-hearted, flirtatious, and maybe a little bit debaucherous. Some of the other Ivies don’t have so much fun.”

Photography by Evan Robinson.

Photography by Evan Robinson.

ELEVEN-THIRTY, MIDNIGHT — that’s the sweet spot. That’s when the DJ spikes, when dancers are drunk but not passed out, when Evan scrambles to shoot 80 percent of his photos in a 35-to-50-minute window. He downs three rum and Cokes so the caffeine hits his system, then sprints into the pulsating beat of the crowd. He doesn’t even look through the viewfinder, just shoots overhead, four feet away from his subjects, jabbing his wide-angle lens to the center of every spilled drink, every makeout, every giggled, garbled sing-along. The DJ blares throwbacks, and it’s all Evan can do to thrust forward into the twirling epicenter of high heels soaked in vodka cranberries, the smartest kids in the city shouting that my loneliness is killing me, and ay-ay …

The perfect party photo starts with light. The LED lights need to come from behind, the glow radiating from the backdrop. But technical considerations are minor.

“Look,” Evan says, “we’ve all been at good parties and we’ve all been at bad parties. The goal is to use these photos to make every party I go to look like the one you wish you were at.”

When the music picks up, he runs across the dance floor. He scours the scene for heads thrown back in laughter, eyes bulging to the size of fists, painted nails and the cascade of bracelets swaying toward an ornate ceiling.

“Think of how many times you’ve been at a party and this one guy lifts his hand over his head and screams with a bottle of vodka, and everybody looks at him like, What a fool, what is he doing? But my job is to get him the second he does that and make him look like the life of the party, because he is leading everybody to the time of their lives.”

A BRUNETTE IN a bandage dress totters over to Evan, asks if he’ll take a photo of her with her sorority little. Days later, she might text him — Hey, can I see that photo you took of me? You didn’t upload it.

Evan will say no.

He curates his photos carefully. Evan takes 2,000 to 3,000 images per night; he rarely sends clients more than 200. When he sees an unflattering photo that he’s shot, he deletes the file.

“I would rather have them think that I fucked up as a photographer than have them realize how awful they looked when they were drunk. That’s the nicest thing to do. Nobody needs to see that.” He sighs. “That’s not the point.”

The point, then, is to offer the image of a perfect night at a school where perfection is more an imperative than a dream. But Evan thinks his photos play a role in a larger story, stretching back to commissioned portraits in medieval times — a point he makes with no hint of irony.

“It’s humans,” he says. “It’s not Penn students. We’re all vain, many of us black out, everybody wants to know what they look like. Everybody wants to think they had a hot date. Everybody wants evidence of the fun they’ve had.”

But evidence comes in different forms, and at Penn, professional photos are the clear winner in the hierarchy of social media projections. It’s about proving a point, about appearing polished and groomed in what are more often than not unruly moments. And when many of the partygoers pass out and forget their nights beyond what a photo captures, only Evan knows the real story.

“I’ve seen it all,” he says. “I’ve seen glasses smashed and girls cry, I’ve watched DFMOs [Dance Floor Make Outs], and I’ve been told, ‘That was not my boyfriend, please delete that photo.’ I’ve watched a bouncer kick somebody out. I’ve seen guys that are so coked out they don’t realize their ear has white on it.”

Besides, Evan chuckles — maybe it’s more efficient to hire a photographer. Perhaps Penn, in all its preprofessional glory, has just figured out how to minimize selfie-taking and maximize party time, at a cost of roughly $125 an hour.

Jack Grasso is a member of St. A’s — St. Anthony Hall, a fraternity on campus. St. A’s social chair hired Evan a few years back, Jack says, and the frat has used him since to shoot some of its events, including its most recent Winter Formal. “It’s good to have pictures of us looking nice to show our parents and to look back on,” he says, suggesting his folks may receive a somewhat edited array of snapshots. Evan’s fee was “not much of the budget at all.”

Emily Johns, a junior from Mount Airy, has been to five or six events that Evan’s documented. She doesn’t usually keep track of who’s behind the lens. “Usually, it’s just like, okay, we’re ready, now let’s go find the photographer,” she says. “And after five minutes, we’re done. But I like having the photographer there. My sophomore year, we didn’t have a photographer, and I was pissed.”

Though Emily says Penn is very different from her high school, Central High in Logan, there was always a kid at Central walking around at parties taking pictures and posting albums.

“There’s a lot about Penn that I could point to and be like, this is excessive and lavish and crazy and no one else anywhere does this,” she says. “This is the one aspect of the Penn party scene that I don’t actually think is weird.”

Photography by Evan Robinson.

BY 1 A.M., the twirling couples have stacked themselves in Ubers and headed back to campus. The DJ slows his set; the tables are cleared. The empty Dom Pérignon bottle responsible for the sticky floor lies sideways on a tablecloth, label ripped and cork vanished. Nothing new to Evan.

“There are some specific guys in certain frats who I have probably seen spray 15 grand of champagne more than once,” he says. “They’re choosing the choicest fucking models, and their tabs are huge, and they just keep doing it.”

His voice picks up. “I’ve seen every version of champagne sprayed. I’ve seen

magnum-sized Grey Goose bottles with sparklers that go off in three seconds while all the drunk girls try to chug it down and the ugly guys with too much cash hit on them. I’ve seen all the variations of it.” And Evan has watched the system recycle, each new crop of former valedictorians from New York and Miami squeezed into spaghetti straps and custom-fit blazers while the upperclassmen gradually thin out.

“Everybody gets tired of it,” he says. “You can only go to the top for so long before you’re only doing it to show off a bit. There’s only so much conspicuous consumption you need to do before it’s not quite fulfilling.”

But whenever Evan gets tired of it, he remembers the people he met, the blue-light-bathed conversations about summer vacations and pets left back home. The whispered, vodka-induced confessions. The moments when these kids could let their guard down, at a school that seems to encourage, above all else, impenetrable invulnerability. The girls who cried through their mascara for two hours, then pulled it together and smiled — click! — just before the flash went off.

Published as “Best. Party. Ever.” in the April 2016 issue of Philadelphia magazine.