The End of the Tank Job: Why the Sixers Stopped Trying to Lose

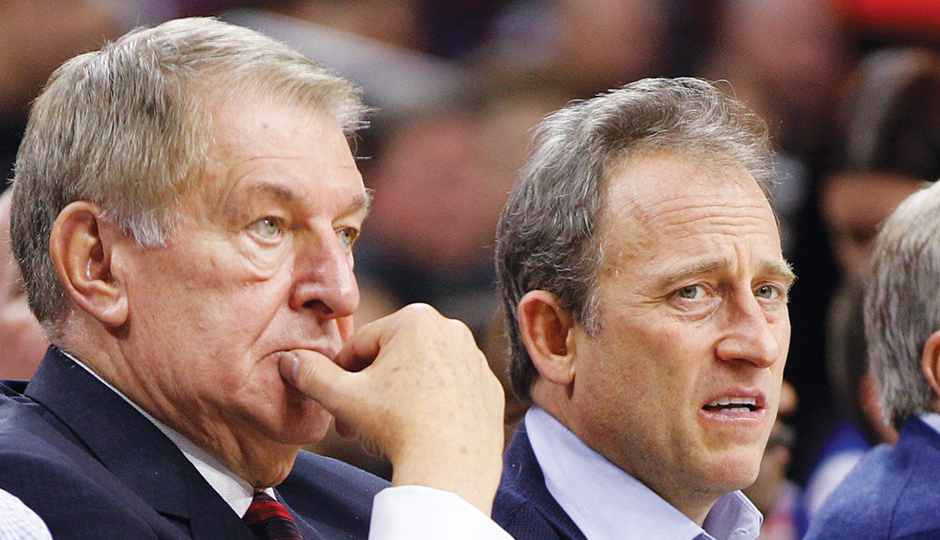

Jerry Colangelo, chairman of basketball operations, and Josh Harris take in another loss. Photo courtesy of the Associated Press.

At the time, it seemed that a punch in Boston was the end of The Process.

Sam Hinkie, the general manager of the Philadelphia 76ers, had devised the bold, open-ended plan to build the team into an NBA champion — which was quickly dubbed The Process, as if it might go on for many years, perhaps forever. But when the Sixers’ young star, Jahlil Okafor, got into an ugly street fight, everything quickly changed.

After the Sixers lost to the Celtics last November 25th, Okafor, then only 19 years old, went out to a nightclub. In the wee hours, he punched a guy to the ground outside the club because he was very unhappy with what the guy said about him and his team, which was that they utterly sucked — the Sixers’ record that night had fallen to 0-16. Someone on the street took a video of the fight, which naturally went viral.

The team, of course, has been bad on purpose, which was step one of The Process. They’ve done a lot of losing: at press time, 172 out of 217 games over two and a half seasons, to get the best picks in the college draft. Every team needs at least one — and preferably two — great players to contend for a championship, and drafting future stars is the surest avenue to the top. Okafor — who will miss the rest of this season following knee surgery — is supposed to be one of those stars.

But there was a growing sense throughout the NBA that the Sixers had taken the losing too far, that it looked bad for the league, that it was unfair to their own coach and players, that they’d reached a point where The Process simply was no longer tenable. The team started this year 1-30. They were not just bad, but a joke.

And then, three days after the fight in Boston, we learned Okafor had gotten a speeding ticket for driving 108 miles an hour on the Ben Franklin Bridge three weeks earlier. And the fight in Boston wasn’t his first. In Old City in October, just as this dismal season was about to start, there had been another one that ended with a gun pointed at an apparently intoxicated Okafor.

As the team was slow responding to any of this — owner Josh Harris and Hinkie were mum about the Okafor incidents — the media had a field day. The 76ers were not only awful on the court; there was no oversight of their young charges after the games ended. Was anybody actually running things?

Harris and Hinkie had nothing to say about that, either. In fact, they rarely talked at all. Their silence — which made the point that they would run their team as they saw fit — was stunning. Meanwhile, we continued to watch coach Brett Brown stand before TV cameras to say with conviction, after yet another loss, things like, “They are 20 years old and I need to help grow them. … I’ve got to wrap my arms around our guys, coach them hard, tell them the truth but also make sure they don’t feel anything else but strong.”

The three of them — the troika running the team — were playing their own brazen game, pretending that trying to lose is a normal course to take on the way to winning a championship. Never mind how upset the rest of the league or fans or the media was getting. They ignored everybody who wondered: Does an open-ended plan like this one ever close? The team might just go on losing. Where does it end?

We now have an answer to that question. It’s not, it turns out, Okafor’s fault that The Process came to an abrupt halt. His off-court problems weren’t the reason Josh Harris brought in an old-school NBA guy, Jerry Colangelo, to run the team less than two weeks after Okafor became a TMZ hit. Or why The Process is now toast.

The story, it turns out, cuts much deeper than a couple of street fights — right back to Harris, the owner, the man at the top. Losing as many games as possible was a very bold attempt to get great. But behind the scenes, Harris really was hearing the noise, the growing criticism, despite his public smugness that Sam Hinkie’s approach was the smart way to go.

In the end, the reason his basketball team is going in a new direction — which looks much like the old way of doing things — is that Josh Harris lost his nerve.

Coach Brett Brown talks mid-game with star center Jahlil Okafor. Photo courtesy of the Associated Press.

THE PROCESS REALLY began as a reaction.

Josh Harris has gotten very rich through private equity investing, specializing in distressed businesses. He zooms in on a company going bankrupt, enlists investors to pick up the debt for cents on the dollar, and often makes an astounding return after downsizing or restructuring said company. In fact, his firm, Apollo, is so good at this that Forbes anointed the investment in chemical manufacturer LyondellBasell Industries the greatest in the history of Wall Street, after Apollo, a major player in the deal, turned a $2 billion investment into $12 billion.

The sort of guy who can pull off deal-making on that level is not quite at home in the world the rest of us inhabit. A business partner remembers a meeting a few years ago in Harris’s New York office, which hovers over Central Park.

“Wow, Josh,” the businessman gushed, taking in the view. “This is awesome. This is really a sweet spot.”

Harris stared, blank-faced, as if there was nothing to say to that. The businessman wondered if he’d offended him. But he soon realized — Harris has no desire, the businessman says, to get to know other people, outside of whatever deal is on the table. He’s guarded, protective, doesn’t share himself. (He declined through a team spokesman to speak for this piece.) Harris doesn’t ask others questions about themselves. So what is he interested in?

“Money,” the businessman says. “Numbers.”

He remembers Harris calling several people to a business meeting at his home in New York a few springs ago. The meeting went on for some eight or 10 hours, and Harris didn’t offer so much as a glass of water to the others — merely because, the businessman assumes, it never occurred to him they might get thirsty. Money. Numbers. They’re all-consuming.

Like a lot of very rich men — he’s worth some $2.2 billion — Harris needed something to do with his money. He’s one of the co-founders of Apollo, but another founder, Leon Black, holds a bigger stake in the company, and Apollo is often referred to as “Leon Black’s firm,” which makes Harris, according to the business partner, visibly shudder. Leon Black collects expensive art, most notably the Expressionist pastel The Scream. Harris needed his own thing, perhaps bigger, or at least more public: sports teams. He kicked the tires on buying the Sixers as far back as 2010, and took a look at getting a piece of the Mets. Eventually, Harris would buy the New Jersey Devils hockey team, and last year he purchased a major interest in London’s Crystal Palace soccer club. He’s an antsy, hedge-his-bets-wherever-he-can kind of guy.

In 2011, Harris took another look at the Sixers. The numbers were right. Ed Snider wanted to sell. The team was losing some $20 million a year and was mismanaged, but it was also undervalued. Those who watched Harris negotiate with Snider’s team were in for a treat. As one Sixers insider says, “I never met anyone less willing to compromise on a deal.” Harris is calm, deliberate; he waits until he gets what he wants, or there is no deal. With more than a dozen other investors, Harris paid $287 million for the team. (It’s now worth about $700 million.)

There was one small problem, however: Harris had no idea how to run a basketball team. But Doug Collins did. Coach Collins fancied himself the toast of Philadelphia, a guy who’d played here and come back to lead a moderately talented team into the playoffs, and according to the Sixers insider, he drew an immediate line in the sand with the new owners, especially Harris — telling him in no uncertain terms that if he didn’t get full power to make basketball decisions, he’d quit. The insider said Collins told Harris that considering Collins’s warm relationship with the local media and the fans, the owner would be screwed if Collins walked. (Doug Collins denies that he confronted Josh Harris. “It’s a fireable offense to speak to someone like that,” Collins says. “I just wanted to coach the team. I did not want full power.”)

Harris caved in to him, according to two Sixers sources, because Collins was the hometown boy, and Harris was on a steep learning curve when it came to basketball. The obsession he supposedly had when he was a student at Wharton, seeing as many Sixers games as he could, was a fabrication, says the insider, who watched the public-relations massaging. Harris’s Philly basketball chops were basically nonexistent.

But Collins’s power didn’t last long. The Sixers insider says the coach had more control of the team than its general manager, and his fingerprints were all over a series of disastrous moves — most notably a major trade for Andrew Bynum, a very big and very good center who had bad knees and would never see the court for the Sixers. Bynum was a bald attempt at going for broke — the team staged an event in August 2012 at the Constitution Center to introduce him — and the acquisition doomed Collins.

So now Harris was drawn to a diametrically different approach, one that paralleled his method on Wall Street of buying companies other investors won’t touch because they’re far too risky. His career had been built on making a sow’s ear into a silk purse over and over again, and now he’d bring his method into another — and much more high-profile — arena.

The team would take its time, find a great player or two through the draft. And they weren’t going to do it halfway. They were going to lose, big, in order to ramp up their draft position. There was another advantage to tanking: In gutting the team of high-priced veterans and signing very young players on the cheap, the Sixers would stop losing money. They’d reap enough from TV contracts to break even no matter how many fans stayed home.

Hello, Sam Hinkie. The Process had begun.

General manager Sam Hinkie holds a rare press conference. Photo courtesy of the Associated Press.

BRED IN A small town in Oklahoma, Sam Hinkie is a natural fit, intellectually, with Josh Harris. Hinkie played football and basketball in high school, and while sports are his passion, he’s a numbers guy, too. He once worked for a Bain Capital subsidiary in Australia, where he found and analyzed businesses to buy — something straight from the Harris playbook — before coming back to America to get his MBA at Stanford.

Hinkie picked Stanford over Harvard for his MBA because of the school’s relationship with NFL teams. Between classes, he worked part-time for the San Francisco 49ers and Houston Texans on player pricing and the salary cap. After convincing Rockets owner Leslie Alexander that he could help the basketball team think more objectively in making player decisions, Hinkie flew to Houston one day a week while he was still in school. Alexander would make Hinkie, at 29, the youngest vice president of an NBA franchise in the history of the league.

In the past decade, all the major sports have gotten on board with analytics, but no general manager in any league more so than Hinkie. The idea is to delve as deeply as possible into what the numbers say about a player, using, for example, the Player Efficiency Rating, which quantifies per-minute productivity, allowing for pace, compared to the rest of the league. Some old-way thinkers still see analytics as egghead hooey, but for Hinkie, using them to predict how good a young player will turn out to be is the obvious way to go. He’s an achievement junkie, like his boss. But as Hinkie explains his thinking, he appears quite different, gentle-seeming and affable, with a bit of Oklahoma twang remaining. He shares his take on analytics with a broad analogy intended to show he’s not a stats geek, but a rational thinker: “You’ll hear, ‘I don’t like numbers,’ or ‘I don’t like probability.’ I say go with your wife to a medical appointment and they say she has breast cancer. There’s only one number you truly care about. You want that number to be right, and if we do this, this happens, and if we do this, that happens.”

From the get-go, when Harris turned to him in May 2013 to run the team in the wake of the Bynum disaster, Hinkie was going to be two things, by design: bold, and a loser. Hinkie traded all-star Jrue Holiday, the team’s best player, along with a draft pick for a skinny 19-year-old defensive whiz named Nerlens Noel, who couldn’t play for a year because of knee surgery (good! The team would stink!), in addition to a better draft pick than he parted with. Hinkie is infamous for being tight-lipped because he doesn’t want other teams to sense his strategy. He certainly studies other GMs. No one understood why Hinkie selected point guard Elfrid Payton in 2014 with the 10th pick in the draft, given that the Sixers already had a good young guard. But then he immediately traded Payton to the Orlando Magic — Hinkie’s sleuthing led him to surmise, correctly, that the Magic had been keen on taking Payton with their pick, number 12. He used that insight to grand advantage, getting future first- and second-round picks and the rights to a terrific Croatian player, Dario Saric, who at the time was contractually obligated to play at least the next two seasons overseas. (We may see him in Philly next year.)

Whew. If all this seems like a big, fast-moving puzzle, that’s exactly the point: It’s high-stakes betting on being able to manipulate other teams out of more than they give back, and Hinkie has proved masterful at it. The Sixers may stink now, but they could have four first-round picks next year.

Yet Hinkie’s aggression, coupled with the sense agents and other general managers seem to have of him as an analytics smarty-pants who often won’t so much as return their phone calls, has burned him. The Sixers insider says, “When Hinkie was in Houston, agents didn’t want their players drafted there, because he’d overnegotiate every contract. He doesn’t have a feel for people, for when to push and when to back off. If he has a slight advantage, he’ll try to turn the knob the whole way.” A rival GM says, “Other general managers roll their eyes when there’s a call coming in from Sam,” because his trade offers are often aggressive to the point of insulting. One agent who repped two Sixers when Hinkie got hired called him three times to congratulate him. He got nothing in return.

I ask Hinkie about the most elementary criticism — that he annoys agents by not returning phone calls. Hinkie agrees it’s a fair point, but then launches down the rabbit hole of just how consumed he is with looking for talent: “We’ve probably had the most players on our team of any team in the past several years. We must have cut the most players. If you’re going to keep looking for diamonds in the rough like Robert Covington or T.J. McConnell, then that by definition means some get sorted out.”

In other words, he’s very busy. You get a picture of Sam Hinkie sitting in his analytics lab, obsessing over the facets of those diamonds. Or flying hither and yon to scout potential “assets,” as he’s often called players. When he uses that term, Hinkie mirrors his numbers-obsessed boss. It suggests he’s involved in a zero-sum game instead of an enterprise that’s much harder to quantify on a stat sheet: the building of a team.

THIS SEASON BEGAN year three of The Process, but even though Hinkie had secured two potential franchise players — centers Nerlens Noel and Jahlil Okafor — they were very young and raw, and their playing styles didn’t mesh. (Hey, nobody said this would be easy.) A third center with All-Star aspirations, Joel Embiid, was sitting out a consecutive season after an operation — his second — on a broken bone in his foot. The rest of the team had been kept not only young but pointedly weak. Harris and Hinkie were still in losing mode, and the 1-30 start surprised no one.

But there was growing unrest around the league. Before the season, Hinkie had made overtures to a couple of high-end free agents, Bulls guard Jimmy Butler and Spurs forward Kawhi Leonard. It wasn’t clear whether he was ready to pull the trigger, to launch a team that actually could win. But there were rumblings that no free agent worth his salt would join the mess in Philly.

Kristaps Porzingis, a seven-foot-three-inch Latvian who can shoot from long range — now those are interesting analytics — was on the board when the Sixers made their pick in this year’s draft. But predraft, as other teams got to examine Porzingis’s physical and work him out privately, the Sixers were stonewalled. According to Deadspin, that led to a confrontation between Andy Miller, Porzingis’s agent, and Hinkie at the end of a June Pro Day event in Las Vegas.

“You said that I would get a meeting with him here,” Hinkie told Miller.

“I said I’d try, and it’s not going to work out, Sam,” Miller responded.

They stared at each other. Miller’s message was obvious: Stay away from my guy. Porzingis now stars for the New York Knicks.

SOME NBA OWNERS had already made it clear they were unhappy with the Sixers’ strategy of tanking games. “Teams did go to the commissioner to talk about it,” says Minnesota Timberwolves owner Glen Taylor. “Some owners felt that it doesn’t look good if a team is not trying to win. And the commissioner talked to me.” Taylor was on a committee in 2014 that proposed a change in the draft lottery intended to make it less likely that the worst team gets the top pick. But the Sixers lobbied small-market teams, pointing out that a change in the lottery could hurt them. The measure didn’t pass.

Coming into this season, coach Brett Brown was seen as something of a tragic figure around the league. He was a brilliant hire by Harris and Hinkie, given that Brown is so preternaturally sunny — and loves to talk as much as Hinkie prefers to stay hidden — that he can pull off coaching a team built to lose as if there’s nothing strange in the assignment. “Look around and enjoy each others’ company,” Brown told his players in the midst of the long losing streak this season. “And you find a level of love for the game. And forget everything else.” This from a coach who cut his teeth leading the Australian national team to some prominence and spent 12 years working for the San Antonio Spurs, an organization as addicted to winning as the Sixers have been determined to head the other way.

Every now and then, though, Brown’s frustration leaks out. He was clearly beside himself when Michael Carter-Williams, just one year removed from rookie-of-the-year honors, was traded last February; Brown says he lobbied Hinkie hard against unloading him, to no avail. At the end of the 2015 season, Brown said, “To coach gypsies, to have to coach a revolving door, that’s not what I’m looking for” — an indictment of Hinkie’s ongoing diamond-in-the-rough search. Last year, when a reporter noted the obvious in a private conversation with Brown — My God, being set up to lose must be so hard — he let it out, an unvarnished moment of truth: “It’s like bringing a knife to a gunfight.”

Still, Brown emerges after every Sixers loss to speak calmly to the press, to convince anyone who’ll listen that this is exactly where he wants to be — trying very hard to win as his owner and general manager try very hard to lose. Meanwhile, a sentiment in front offices around the league this year began to take root: Philly better start winning. Losing at a record pace simply can’t be sustained as a method without end.

The Sixers spent almost the entire first half of the year with no real point guard, meaning no one who could effectively get the ball to the ballyhooed big men — Noel and Okafor — who did represent some hope. It was painful to watch. The horrible beginning of this year felt even worse than the 0-26 stretch the team went through two years ago — a run that tied a record for the longest single-season losing streak of any team in the major sports in North America ever. When I speak with Brown, he refers to the period in mid-December as particularly “vulnerable.” He worried that his team’s spirit was waning. Until then, they would come up short, but they would play their hearts out. Now, the bad play and the losses began to feel as though they’d overtaken the Sixers — that there was nothing they could do to fix it. As if this was simply who they were. Losers.

While the team continued its downward spiral, Josh Harris, who was still frequently attending games, would get booed — the fans were clearly getting restless. So was the league. Word continued to spread, through the commissioner’s office, about how fed up other owners had become. The Sixers insider says the league’s board of governors considered the Sixers’ tanking cheating, and that it believed Harris was gaming the system. Harris was also hearing complaints closer to home, with at least one minority owner of the Sixers in his ear: People are laughing at us. There has to be a better way than this.

Then, in November, Okafor got into the street fight in Boston. In the video, a heckler mocks his bad team, and Okafor yells back, “We got money!” Punches were thrown. It was ugly. The other news followed: speeding over the bridge, the Old City fight that ended with a gun pointed at him, and video of a second street brawl on that night in Boston. It was Coach Brown who broke a week of near-silence on the subject of the Sixers’ young star, before a game in New York. (Hinkie, who was at the arena that night, refused media requests to speak about Okafor.) Brown announced that the center had been suspended for two games and that it was time for “tough love.”

In late December, I started visiting the Sixers locker room, mostly to try to figure out the deal with Jahlil. It’s a tricky proposition, to judge a 20-year-old across vast differences in age and occupation and stardom. (Okafor has been feted as a prodigy since he was 14, and last year he won the national championship at Duke.) But I chatted with him before several games to see if I could get some feel for who he might be. Quiet, deep-voiced and polite, Okafor won’t talk about the late-night incidents, naturally. Before a game against Memphis, we shared a bit about our pets; he once said that if he didn’t play basketball, he wanted to be a vet. Okafor has a Rottweiler named Natty, and I told him I was concerned about my cat, who had blood in his urine. “I’m sorry to hear that,” he said. Before the next home game, I went up to Okafor to tell him, “I’m the guy with the cat pissing blood.”

“I remember,” he said.

“He’s doing better.”

Okafor smiled. “Oh — that’s good to hear.”

Before a third game, I asked him if he still nods to his mother just before tip-off. A couple years ago, he told a Chicago writer the story of how his mother died, when he was nine, of a collapsed lung. It was Okafor who discovered her breathing hoarsely, but by the time he understood that she was in trouble and ran to get help, it was too late. Before games, he would whisper, “Let’s go, Mom. I’m ready.” He told me that he still does.

I’m not foolish enough to think my moments with Okafor gave me some reading into his soul, but I do get the sense that what others around the team tell me — “Some guys come along, you just sense in the locker room or watching them that they’re not the best of citizens,” says one longtime Sixers employee, “but I don’t get that vibe at all from Jahlil” — is believable. And that the heat the Sixers took in the aftermath of Okafor’s Boston fight is legit, too. Okafor’s agent, Bill Duffy, says the rookie found all the losing “basically shocking,” given that in two months he’d suffered through more defeats than he had experienced in his basketball life in total. He was unprepared for it, and reacted badly. The Sixers, who have since beefed up their security around Okafor, did him no favors.

Which speaks to what a former team executive told me about Sam Hinkie: “I don’t think he realizes the emotional aspect of losing, the way it creates tension, how it wears them out. They’ve been winners their whole lives, and he’s creating a culture of losing. I don’t think he understands what that does.”

As Sixers management took a public thumping for providing no direction to the youngest team in the history of the league, Harris made his move. He went to league commissioner Adam Silver.

But it wasn’t primarily because of the hubbub over the team’s handling of Okafor. It was what Harris’s fellow team owners, and even minority owners of his team, were saying. It was the media, and the fans. Silver often privately shared his hatred of the team’s method with the Sixers insider; it was making the NBA look bad. All of this was bubbling up, ready to blow. Silver also told the Sixers insider that Harris now confided to him that with all the nasty things people were screaming at him, he was worried about his physical safety at Sixers games.

His tarnished image as the Sixers’ owner isn’t helped by speculation that Harris is nearing his end game here, and that he’ll flip the team as just one more business to unload at a profit. Forbes reported that his real desire is to bring an NFL franchise to London, and that he invested in soccer there last year to get a foothold in the European sports world. But pro football is the most exclusive fraternity of big-league sports ownership, and Harris getting into that club after his stewardship of the Sixers is pretty unlikely. In his defense, both Timberwolves owner Glen Taylor and Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban praise how involved in league matters — various committees and so forth — Harris has been, despite what some other owners think of his methods.

Yet even with a few supporters inside the league and a vocal minority of fans who still believe in Hinkie’s tear-down plan, Harris — so patient and tough on Wall Street in making billion-dollar deals — could no longer hold the line on maintaining the worst team in professional sports. He told Silver that he had to have some help. Silver said that he needed Jerry Colangelo, and Harris said yes. With that move, The Process was over.

JERRY COLANGELO IS a dapper, pleasant, talkative man of 76, which happens to be twice Sam Hinkie’s age. He lives in Phoenix, and he’ll go on living in Phoenix, even though Josh Harris hired him in December to oversee the Philadelphia 76ers as the director of basketball operations. Quickly, changes were made: The Sixers traded two second-round draft picks (normally, Hinkie stockpiles those) for point guard Ish Smith, who played for the team last year but whom Hinkie let go; immediately, the Sixers won a handful of games. Respected veteran Elton Brand, who thought he had retired, was signed by the team to mentor Okafor and the other youngsters. Clearly, Colangelo was in charge. And it didn’t take him long to do something Hinkie never would — proclaim that the team will get better sooner rather than later.

I spend an hour with Colangelo in the team’s offices in the Navy Yard, and right off the bat, he launches, unbidden, into the story of just who he is, beginning with his first NBA job with the Chicago Bulls in 1966 — when he sold season tickets by tossing pamphlets off the back of a flat-bed truck. He would fly to Phoenix two years later, to see if he wanted to create a team there.

“I had never been to Arizona. By the end of the day I’m being pressured to accept a deal. Here’s what I saw: I saw a blank canvas, and it came to me, at that age: This could be an opportunity to do something on your own — you paint it. So I got to a phone and my wife picked up, and I said, ‘Pack your bags, babe. It’s Phoenix.’ Two weeks later, I took our three kids, nine suitcases, 300 bucks in my pocket, and got on a plane. I never looked back. I was 27.”

With that, before Jerry Colangelo has been asked a question, he has answered the only important one, which is: What is he doing in Philadelphia?

The man who created professional basketball in the Southwest, and brought Major League Baseball there to boot, and who now runs USA Basketball and is chairman of the NBA Hall of Fame and has gotten very rich making land deals in the farthest reaches of the country, the man who knows everyone in the sport and whose handshake has been gold to seal a deal for half a century, the man who said that Josh Harris “pleaded” with him to come East to save the 76ers, and said that when he first arrived in Philly, Brett Brown fell into his arms and told him, “Boy, do I need you” — he’s the man who couldn’t resist the challenge to take it on. To come flying in and resurrect this team.

To that end, there’s another Colangelo story to share: In 1969, there was a coin flip for the first pick in the college draft. It would go to either the Milwaukee Bucks or the Phoenix Suns. The Bucks won. They chose Lew Alcindor, who would soon change his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. The Suns ended up with a guy named Neal Walk. You’ve never heard of him for a reason.

With Walk, the Suns won 39 games — almost half of their total. “I coached the team the second half of the year,” Colangelo tells me proudly, “and we made a run. We had the Lakers down three games to one in the playoffs.” Before losing. Most expansion teams are awful for years, but in just their second season in the desert, his team had attained mediocrity — a surprising achievement. The Suns then found the good groove that would define them for most of their existence, the sort of never-quite-good-enough-to-win-a-championship limbo that Josh Harris and Sam Hinkie had been determined to leapfrog here in order to get great.

So it’s on to what Harris calls The Next Phase. After starting with old-school baller Doug Collins, after trying Sam Hinkie’s radical approach, Harris has bounced back to a true basketball man. No one knows exactly what The Next Phase will bring, though it’s clear that in losing his nerve, in caving to the growing crescendo that he was making a mockery of running a team, Josh Harris picked the safest guy he could find.

Which is why Jerry Colangelo, who has never won a championship in his long career, is now in charge.

Published as “Courting Disaster” in the March 2016 issue of Philadelphia magazine.