The History of the Philly Boo

The genesis — and consequences — of Philly’s sports anthem.

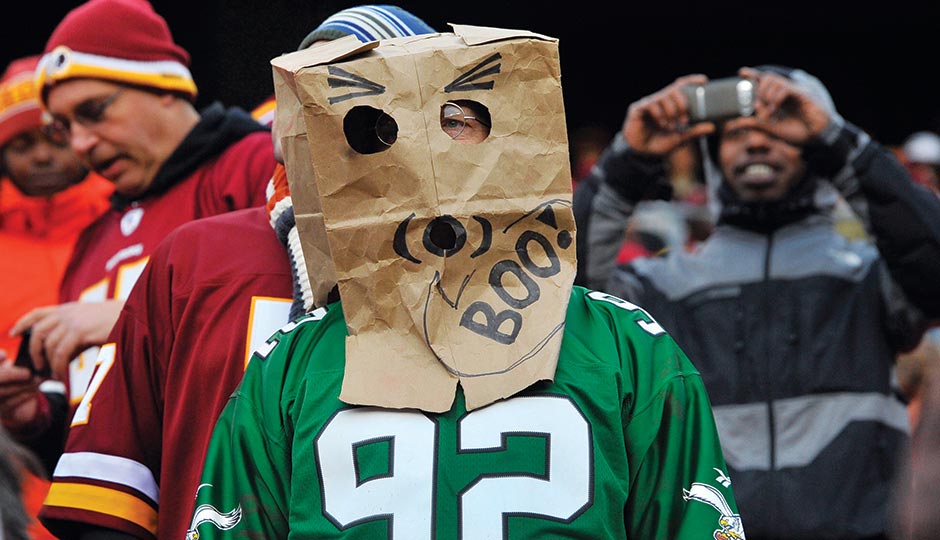

Mark Gail/MCT/Getty Images

As the clock wound down in the second quarter of the Eagles game against the middling Tampa Bay Buccaneers, the visitors had already piled on four touchdowns. All signs — particularly the Birds’ defense, which resembled matadors and turnstiles — pointed to a rout. In the wake of a heartbreaker loss to the lousy Miami Dolphins the week before here at home, a letdown against the Bucs had season-ending implications. The fans knew this. Which is why, as the players jogged off the field at halftime, a shower of boos rained down. These weren’t your garden-variety “We’re not happy” boos. This was a deafening, guttural roar. A seismic display of frustration. A tsunami of “You suck.”

I watched this debacle unfold from the lower corner of the end zone, above the tunnel that leads to the opposing locker room. On their way off the field, two Tampa Bay players smiled and laughed with each other. Impossible to say what joke they shared, but I imagine it had something to do with how loud the booing was, and how tough it must be to wear midnight green in Philadelphia. I was too depressed to jeer along with the crowd.

After the game, Philly Mag’s own Josh Paunil, of Birds 24/7, asked offensive lineman Lane Johnson about playing at the Linc. The poor guy took the bait: “If we get down by any significant amount of points or we don’t make any first downs, we’re going to get booed,” Johnson said. “That’s just kind of how it is. It’s not really home-field advantage playing here anymore. Really, that’s the truth. Cats here, they really don’t care.” Johnson later tried to explain he wasn’t criticizing the fans (a backtrack precisely no one bought) and eventually apologized (on Twitter, of course).

Philadelphia isn’t the only town that boos its home team (see also: Bronx Cheer). The word “boobirds” dates back at least to 1948 in a reference to Cleveland, one of the few fan bases more downtrodden than our own. Yet the sound is especially potent here, a vocal bomb that’s deployed often and aimed at opposing teams (Dallas, in particular), loathed athletes (Sidney Crosby), referees (pretty much all of them), and vaguely unsportsmanlike tactics (the slightest hint of a faked injury to slow down the Eagles offense). It also cuts both ways, given that we often direct this weapon of sass destruction at the home team. The day after the Eagles lost 45-17 to the Bucs, the Daily News cover headline read, simply, “BOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!”

With three of our four teams currently best described as “historically bad” or “soul-crushing,” no word captures the state of Philadelphia sports better than “boo.” After witnessing the fury unleashed at that Tampa Bay game, I started looking into the history of the boo in this town. I found a startling fact: For all our talk of home-field advantage, since the Linc opened in 2003, the Eagles have been slightly more successful on the road (62-47-1) than in South Philly (62-49). Could Lane Johnson be right? Is booing the home team bad?

THE PRACTICE OF heckling dates back to the ancient Greeks (which is fitting, given that Dionysus is essentially the god of tailgating). Cheering or jeering playwrights was considered a civic duty, like wearing sandals and building fancy columns. In Rome, hissing a gladiator didn’t just hurt his feelings; it was often a death sentence. (Puts the old 700 Level crowd in perspective, doesn’t it?) The word “boo” has been traced to England in the early 19th century, when it was used to describe the groaning of cattle — also fitting, given the way fans file in and out of stadiums to pay $12 for a beer and watch bad teams lose.

By the 1900s, booing was synonymous with the howl of unhappy crowds, and there’s evidence to suggest that Philadelphians were early masters of the form. A Sporting News article from 1910 contained this gem: “Do not blame unruly baseball behavior on foreigners, since it is long commonplace in Philadelphia.” In The Great Philadelphia Fan Book, authors Anthony Gargano and Glen Macnow recall the Kessler brothers, who were the Yannick Nézet-Séguins of home-team trashing. The pair sat on opposite ends of the diamond at Shibe Park and conducted mass jeering of the Philadelphia A’s for nine innings. Their haranguing was so toxic that team owner Connie Mack sued the pair to shut them up. Mack lost, and in the ultimate display of devotion to shouting in public, the Kesslers rejected his offer of free season tickets in return for their silence.

Our national reputation for booing may have been cemented in 1930, when President Herbert Hoover was welcomed with it during Game Two of the World Series between the St. Louis Cardinals and the A’s at Shibe Park. The same scenario played out the following year, when both teams met for the championship again, inspiring a New York World Telegram sports editor to describe the sound as “a vigorous, full-rounded melody of disparagement.”

The 1960s brought the blossoming of the modern boo age, inspired by the collapse of the ’64 Phillies and, especially, the calamitous five-year run of Eagles head coach Joe Kuharich, who compiled a 28-41-1 record. “It wasn’t just a couple disgruntled people,” recalls Ray Didinger, the Hall of Fame sportswriter and copious-note-taking analyst on CSN’s Eagles post-game show. “You had groups of people taking out ads in the paper, and organized protests. A plane flew over Franklin Field with a sign that said JOE MUST GO. Kuharich was the first person to take the boobirds and galvanize them as a flock.” This was booing as a mass movement, a union of dissatisfied fans. “That was the first time it took on real hostility,” says Didinger. “It was nasty. It was beyond booing a bad play.”

A brief respite came in 1980, when all four Philadelphia teams reached their championship games — a feat no other city had achieved before or since. Gargano, now the morning-drive host on 97.5 The Fanatic, was a product of that era. “I was born during the generation when things were good, so I always had a more positive outlook,” says Gargano, who swears he’s never booed. “I was 10 and everyone went to the finals. That affected my sports view. The older guys were nasty — ‘They’re bums!’ And the younger guys, there’s some nastiness, too.”

Those younger guys (and women) watched as every few years, their teams came close but never clutched a trophy: The ’93 Phillies, ’97 Flyers, ’01 Sixers, ’04 Eagles and ’10 Flyers all lost in the championship round. Even the euphoria of the 2008 Phillies World Series victory faded as the team slowly tumbled back into baseball’s cellar. “I would have thought the boo would have softened,” Gargano says of today’s fans, many of them craft-beer-drinking, artisanal-mustache-cultivating types who’ve experienced at least one parade. “The boo hasn’t changed.”

Yet its delivery system has. The 2016 variety of boo is inescapable. It lives not only within arenas and ballparks, but also online. Athletes used to avoid reading newspapers and listening to sports-radio chatter — or said they did, anyway. Good luck escaping the criticism today. Eagles linebacker Brandon Graham estimates he’s blocked 500 fans from his Twitter account for their virtual heckling. Some players even have to worry about their own families — witness the vulgar tweets of Michael Vick’s brother, or the rants of a woman claiming to be KJ McDaniels’s mom about the “disgraceful” Sixers who drafted her son. “Fighting in the stands is actually softer than what’s on Twitter,” says Gargano. “There’s no consequence to the boo.”

Perhaps, though, there is.

RAY DIDINGER’S GRANDFATHER owned a bar at 65th and Woodland, and he helped his regular customers — working-class guys from the neighborhood — pay for their $18 Eagles season tickets in installments. Young Didinger would ride a bus with that crew from the bar to Franklin Field each Sunday. Wretched as those Eagles were, no one from the bar booed. Didinger once asked his father how reviled quarterback Norm Snead could be so lousy. “He’s doing the best he can,” his dad replied. Says Didinger: “My family just drilled into us that you don’t have to cheer, but you don’t boo.” Such a measured, restrained sentiment from a lifelong Eagles fan is at once both Rockwellian and something out of an Eagles-themed Twilight Zone episode.

Today, the boo is a birthright for most Philly fans. But the civility of the Didinger family and Lane Johnson’s comments made me wonder — against every instinct I have as a Philly sports die-hard — if we should give it a rest with the booing. When Steve Mason lets in four goals in the first period and gets the hook, he’s no less upset than we are. A lusty round of boos doesn’t help matters.

Sports psychology research suggests that razzing the home team can have a negative impact on its performance. The effect seems to differ from sport to sport and skill to skill; one study found that basketball players shooting free throws were immune to booing, while other hoops research saw an increase in turnovers and fouls when fans applied pressure. Booing can increase player aggressiveness, which may lead to mistakes (think: pitchers trying to strike out a batter by overthrowing, or a linebacker making a big hit instead of a secure tackle).

None of those studies examined the millennial athlete, and anecdote suggests younger players are even more sensitive. After Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie fired Chip Kelly in December, he described his ideal coach as having “emotional intelligence,” a guy who will “open [his] heart to players.” Among Lurie’s athletes who may need a hug is Lane Johnson, age 25, who has been a Bird for three whole seasons and is already complaining about hearing boos. When street-fighting Sixers center Jahlil Okafor was still in high school — a little over two years ago — he told Chicago magazine that mean comments on Twitter hurt his feelings: “I wonder if they would say negative stuff if they realized how nice I am.” LeSean McCoy was so mortally wounded by getting traded to Buffalo that in his rematch against the Eagles, revenge seemed to be his priority.

There is no one in the Philly sports universe — or maybe any other — with a more Zen outlook on life than Bernie Parent. The two-time Stanley Cup-winning Flyers goaltender is a devotee of mid-aughts best-selling self-help book The Secret, which reduces the complexity of life to this message: The positivity you send out into the world comes back to you. On the matter of booing, I figured Parent would encourage fans to focus on the positive — to lift their teams up instead of tearing them a new one. Instead, he has a message for his fraternity of fellow players.

“My philosophy is very simple,” Parent says. “People come out for two, three hours of their lives. They escape from the real world and whatever problems it can create. When people boo — and it’s not just in Philly, it’s everywhere — players have to realize, you’re not playing well.” Parent acknowledges that at the height of his career in the ’70s, the gap between athletes and fans was a narrow one. Those Flyers teams wined and dined with the common folk in South Jersey and Center City; they were relatable guys, real human beings. Most athletes today live in an alternate reality. They’re more like Hollywood celebrities than members of the communities where they work. That dehumanization makes it easier to pull the trigger on a round of boos, or tweet “You’re a bum.”

Changing times aside, Parent’s advice to athletes frustrated by their fans is both old-school and thoughtful: “When I was playing, I didn’t compete against anyone else. I competed against myself. I tell young players: Learn to communicate with people. Tell folks: ‘I’m working very hard to get to the next level and get better results.’ Players make a lot of money today. When you’re on the field and it’s filled with people, where do you think that money is coming from?” Parent adds a plea for unity: “Don’t say, ‘We’re the players and they’re the fans.’ We’re all one big family.” (Strange to think a Broad Street Bully is the Gandhi of Philadelphia sports, but there you have it.)

Money, of course, is what separates sports from family. Athletes know they can be traded or cut, and fans understand their heroes may skip town for a big payday elsewhere. But like that ne’er-do-well relative who needs a talking-to every now and then, we’re hard on our athletes. Philly, like New York and Boston, is a tough-love town. No matter how sweet a spiral you throw or how lethal you are from beyond the three-point arc, if you need coddling from fans, this town isn’t for you. Likewise, emotional fortitude — what Didinger calls “rhinoceros skin” — should be as important to the Sam Hinkies (and whoever calls the shots for the Eagles at this year’s draft) as 40 times and wingspan.

Here’s what’s certain: The boo isn’t going away. The pastime reached new heights at the Linc three weeks after that Tampa Bay game, when officials upheld a critical interception by the Buffalo Bills. On replay, the pick looked similar to an earlier catch by Eagles receiver Riley Cooper that was reviewed and called incomplete. Fans anticipated a reversal. So when the Bills were given the ball, the crowd gave the refs the business. Television cameras caught Jeffery Lurie, up in the owner’s box, waving his arms in disgust at the call. Then something shocking happened. Even the worst lip reader could interpret what he was saying. Mouth open in that old familiar pucker, the most powerful man in Philadelphia sports booed.

Booing is who we are. But perhaps the fans and athletes can meet somewhere in the middle. When we buy a ticket to a game, we also bear some responsibility. Like it or not, our bad vibes may impact our players for the worse. So let’s wait until at least halftime to unleash the boos, and try channeling our inner Didinger the next time a goalie gives up a soft one. As for the players: Accept the boo as part of the job, one that predates you and will outlive us all. No one will fly a YOU SUCKED banner over your funeral. Promise.

Published as “The Score” in the February 2016 issue of Philadelphia magazine.