The Brothers’ Network Wants to Change the Way You See Black Men

In its role as a producer, The Brothers’ Network has showcased both established and emerging African-American theatrical talent. Seen here: “Hands Up: 6 Playwrights, 6 Testaments,” which it co-produced with Flashpoint Theatre Company this summer.

To understand why the Brothers’ Network exists, it might help to share the tale of an experience its founder and creative director, Gregory Walker, had at a local coffee shop not too long ago.

He walked up to the counter and asked the barista for an espresso. The barista replied, “Have you ever had an espresso? Do you know what it is?”

“I’ve been drinking espresso since 1980,” Walker explained as he related the incident.

It seems that many Americans, white, black and in between, view black men through a certain frame of reference that fails to acknowledge the totality of the black male experience. At the museum, the black man is the security guard rather than the person who created the works on the walls; at the theater, he is the usher rather than part of the action on the stage or the person behind that action.

And in the everyday world, the black men who do create works of art, who do write plays, and who love to talk about the ideas they advance, get confused for those guards and ushers.

Walker founded The Brothers’ Network in 2006 to eliminate that confusion and put in its place a new frame of reference, one that recognizes what he calls “the multiplicity of identity” of black men.

“What we do is dismantle assumptions,” he said.

TBN’s chief building material in this deconstruction/reconstruction project is the very stuff found in museums and theaters, as well as in concert halls, on tables and in between covers: namely, creativity and ingenuity. The organization specializes in bringing brainy black men together around arts and culture, where they can then engage their brains around the ideas and issues raised by the cultural works they contemplate. Book discussions, conversations with playwrights, docent-guided gallery tours and artist talks, wine tastings, and the like are the tools used to carry out the reshaping.

And as they go about this reshaping, the people who attend TBN programs form a new community, one in which they no longer feel isolated.

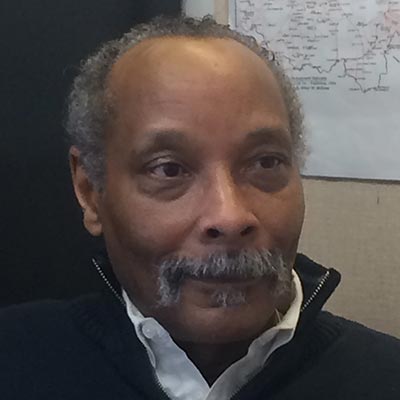

Roland Williams, Ph.D.

Roland Williams, professor of English at Temple University, is one of those people who found a new community through engaging with TBN.

“The Brothers’ Network has allowed me to know more not only about places and events, but also more people,” he said. “I’ve met lawyers, financiers, real estate developers, artists and even artisans through my involvement with The Brothers’ Network.”

And that in turn allows Williams to expose the students in his classes to what Walker calls “the possibility of possibilities.”

“I’m always teaching against the kind of false representation [of black men] that’s given by the mass media,” said the author of “Black Male Frames: African-Americans in a Century of Hollywood Cinema, 1903-2003.” “If you’re growing up as a young black male today, it would make sense that you would aspire to become a basketball player, because you can most readily see that as an avenue to success. You cannot see that same avenue in other professions, and TV does not offer black men many positive role models to evaluate.

“The Brothers’ Network has broadened my horizons and my awareness of African-Americans, and that awareness I take into the classroom to offer my students more role models, more avenues that they can pursue — avenues that in most cases they weren’t even aware of.”

E, Mitchell Swann

Just about everyone who has become involved with The Brothers’ Network can tell a similar story. E. Mitchell Swann, a LEED-certified professional engineer and principal of MDC Systems, a Paoli-based construction management and consulting firm, had heard about the organization in its early years, when its activity centered on book discussions; an avid art and music lover, his first serious engagement with the organization came in the form of financial support for one of its first theater-related programs, a discussion focused on The Mountaintop, Katori Hall‘s reimagining of Martin Luther King Jr.‘s last night on Earth.

The reaction some people had to the whole idea, he said, could be characterized as: “You can’t have this kind of refined, culture-based thing among African-American men; they don’t read, they won’t go to these things.” Which he knew not to be true: “I go, and I’m an African-American man, so there’s at least one data point to prove that wrong.”

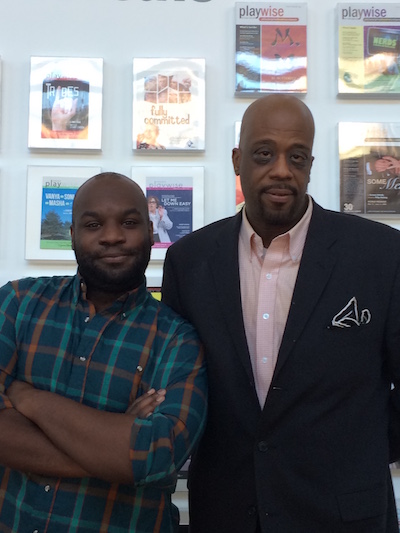

Playwright Ike Holter (left) with Brothers’ Network Creative Director Gregory Walker. Photo | Sandy Smith

The success of the Mountaintop program at the Philadelphia Theatre Company led to a partnership between TBN and PTC that endures to this day. The latest fruit of that partnership is this Saturday’s event that features a pre-performance conversation with Ike Holter, a young (30 years old) playwright who has taken his hometown of Chicago by storm. Holter’s latest play, Exit Strategy, looks at politics and community activism, among other subjects, by telling the story of a group of residents of a poor South Side Chicago neighborhood who band together to save their local school from closure.

It’s a subject that should resonate locally, as the School District of Philadelphia’s ongoing financial woes have triggered waves of school closings accompanied by impassioned campaigns mounted by neighborhood residents to save their local schools.

Holter explained that he seeks first to tell interesting stories, then to deliver something to make audiences think. “The important thing for me as a writer is to find something that people want to see, and then, about a third of the way into the story, they discover that there’s another conversation going on here.”

“Heirloom” by Cosmo Whyte

Like the other artists TBN has promoted through its activities, Holter uses material rooted in a particular experience to address universal questions. “I was always told as a young artist that good work transcends boundaries, so even though you should immerse yourself in something specific, that work can transcend and inspire those who have not shared that experience,” said artist Cosmo Whyte, a professor of fine arts at Morehouse College and TBN board member. Whyte’s first exposure to the organization came when he was invited to participate in a discussion on the work of Anglo-African artist Yinka Shonibare at the Barnes Foundation two years ago, and he was so impressed by both the turnout and the level of engagement that he decided to join the board.

That sort of deep engagement also characterizes the connections among TBN members. Research conducted several years ago by Dr. Kenneth Smith, formerly of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health and now at the University of Texas Medical Branch, found that Brothers’ Network members felt more connected to one another and to their community as a result of their participation in its activities.

(Full disclosure: This writer is another black man who found TBN’s message and mission appealing. I regularly participated in those book discussions in its early years, have attended several other programs in the years since, and formerly edited the organization’s email newsletter.)

The notables who have participated in TBN activities also value the connectedness and support its members provide. “We hosted the author Nelson George for a book talk, and he was overwhelmed by the turnout,” Walker said, adding that George said he had never had that many African-American men turn out for a book talk by him before.

TBN has become especially adept at bringing black men and black playwrights and artists together for mutual benefit. Besides PTC, the organization has partnered with a number of other theater companies both in and beyond Philadelphia, including the Arden Theatre Company, Plays & Players Theatre, and the Hartford Stage Company in Connecticut, and showcased and used as a springboard for discussion works by some of the most celebrated young African-American playwrights of our day, including 2013 MacArthur Fellow Tarrell Alvin McCraney, two of whose works—”The Brothers Size” and “Marcus: or the Secret of Sweet,” the group co-produced with Simpatico Theatre Project and Plays & Players Theatre respectively. Theater companies welcome the audiences TBN brings—more than 1000 people came to see McCraney’s plays during their Philadelphia premieres—and members enjoy additional opportunities for cultural and interpersonal connection.

Its most ambitious project to date could be considered a literal metaphor for what TBN seeks to do in the larger society: The Henry “Box” Brown Festival, a multimedia, multi-disciplinary series of performances, conversations, symposia and exhibit tours staged in 2013 and organized to honor one of the most audacious escapes pulled off by an American slave: Henry Brown got his nickname by shipping himself from Virginia to Philadelphia and freedom in a wooden box in 1857, making him an instant celebrity among abolitionists in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Funded by a grant from the Knight Foundation, the festival used the box as an organizing principle to “unpack” the hidden genius that resides in black men.

TBN continues to expand both its geographic reach and its subject areas: it has sponsored conversations with Holocaust survivors as a way of showing the universality of the struggle for freedom and dignity, hosted art exhibitions in Washington and returned to its roots with a new series of book discussions. It also has plans to add more cities to its roster in the years ahead. In a year when “Black Lives Matter” has been a phrase on the lips of many, The Brothers’ Network has made it its mission to show that the phrase extends well beyond the boundaries others have erected around the lives of black men.

The Brothers Network hosts Ike Holter in conversation at the Philadelphia Theatre Company‘s January 30th performance of Exit Strategy at the Suzanne Roberts Theatre.