The Philadelphia 76ers Lost Defensive Identity

Figuring out how to play Jahlil Okafor and Nerlens Noel together has been a challenge for Brett Brown on the defensive side of the court. | Bill Streicher-USA TODAY Sports

The Sixers’ offense is bad.

Really bad.

As a team the Sixers average 94.1 points per 100 possessions, easily the worst in the NBA. In fact, that would be the third worst offensive output over the last 20 years, behind only the 2002-03 Denver Nuggets (92.2 points per 100 possessions) and the 1998-99 Chicago Bulls (92.4).

It’s also a slight drop from last year’s already bad baseline of 95.5 points per 100 possessions, which was itself a drop from the 99.4 points the offense produced during Brett Brown‘s first season as head coach.

Because of that it would be easy to blame the Sixers’ 1-28 start on the offense. And, certainly, the offense prevents them from winning at a high level, and is something that will hopefully be corrected as the Sixers add more high level talent to their roster.

The Sixers found themselves in a similar position last year, sitting at the bottom of the league with a 2-23 record when they squared off against the Orlando Magic on December 21st. But the Sixers “turned their season around” — and by turned their season around, I mean won enough games to avoid the records for futility that they seemed destined to destroy — not on the back of offensive improvement, but from a defensive mindset that became a legitimate identity for Brett Brown’s young team.

Poor offensive play, spearheaded by an inability to protect the basketball, is something that has been a (depressing) defining characteristic of this team during the majority of its rebuild. In fact, some of the offensive statistics the Sixers have put up during their infamous start to the 2015-16 season look eerily reminiscent of their futility to start the 2014-15 season as well.

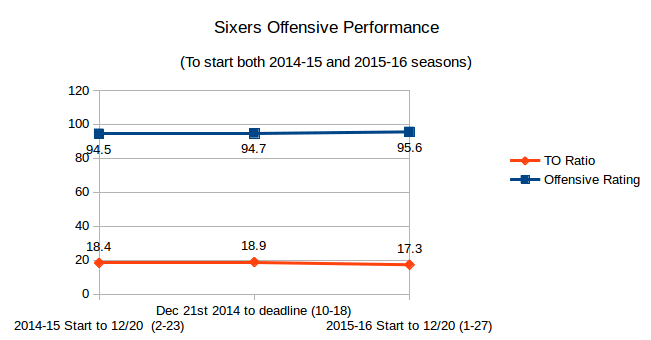

But here’s the thing: when the Sixers turned their season around, going 10-18 from December 21st, 2014 up until the 2015 trade deadline, those same pitiful offensive metrics still existed. They still couldn’t score, and they were still far too careless with the basketball.

Offensive performance, per 100 possessions, to start the 2014-15 and 2015-16 seasons. All data from nbawowy.com. Offensive rating is points scored per 100 possessions, and TO Ratio turnovers committed per 100 possessions.

If those numbers look shockingly similar, they should. The Sixers are currently a horrible offensive team that turns the ball over way too much. They were also a horrible offensive basketball team that turned the ball over way too much last year, and they remained a horrible offensive team that turned the ball over way too much even when they started playing competent basketball before the All-star break.

In fact, you could (quite easily) argue that the Sixers have a better half-court offense now than they had during that aforementioned 10-18 “sprint” to the trade deadline that restored a level of respectability. Whereas last year’s team was heavily reliant on fast break points to score, averaging 14.8 fast break points per game between December 21st and the trade deadline, this year’s Sixers team doesn’t generate those easy looks. Instead, this Sixers team averages just 10.5 fast break points per game.

That provides some faint glimmer of hope — this year’s Sixers team actually scores more points per possession in the half-court than they did last year, and turn the ball over less than when they were confined to the half-court last year as well — but the fact that the Sixers defense struggles so mightily to force turnovers and generate easy looks for the offense is itself representative of the struggles they’re facing on the defensive side of the court.

When the Sixers became competent and watchable last season it happened not through drastic offensive improvement, but on the back of their rapidly improving defense. That defense, which was a top-10 defense in the league from December 21st to the trade deadline, gave the Sixers an identity, something they could hang their hat on, something which kept them in games and helped them regain confidence.

That identity is gone.

That top-10 defense is now the 26th ranked defense. It generates a third less fast break points than it used to, and forces the Sixers flawed half-court offense to try to do even more than it previously had to. Whereas the Sixers during their 10-18 run up to the trade deadline actually outscored opponents, 14.8 to 13.8, each night on the fast break, this year’s Sixers club is outscored by nearly 6 points per night in transition.

The addition of Jahlil Okafor to this Sixers team is a contributing factor that cannot be ignored. Okafor has the type of physical limitations — slow laterally, doesn’t change direction all that well, not an explosive leaper to alter shots — that requires he be quick with his defensive recognition. He just doesn’t have all that much margin for error in his reaction time in order to be a competent team defender.

It’s physical limitations that are possible to overcome, Grizzlies big man Marc Gasol is proof of that, but Okafor needs to see and react to the game at an exceptionally high level to make this happen, and right now he’s at the other end of that spectrum. Combining slow recognition without an ability to quickly recover is a recipe for disaster.

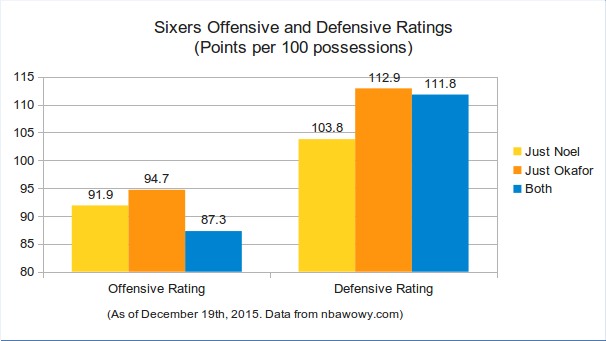

And so far that’s played out, as the defense has, rather consistently, performed better when Okafor’s been on the bench. With Nerlens Noel as the only true big man the Sixers give up just 103.8 points per 100 possessions, which would be in line with last year’s results, which had the Sixers allowing 106.0 points per 100 possessions, and 103.7 with Noel on the court. With just Okafor on the court, this year the Sixers allow a shockingly bad 112.9 points per 100 possessions*.

It puts the Sixers in a tough predicament, because Okafor is showing more and more signs of helping the Sixers’ offense. Whereas at the beginning of the year the offense was clearly flowing better without Okafor on the court, in large part because the Sixers were turning the ball over at a prolific rate, that hasn’t been the case of late.

As Okafor’s free throw shooting, perimeter shot, and pick and roll play improve, and as the Sixers surround Okafor with more cutters and he’s able to make use of his passing ability more, it’s getting easier to envision designing a competent NBA offense around him.

(Note on Okafor’s passing: that has been one of the most frustrating parts of his game so far this year. Okafor handled double teams at Duke with a deftness that was unique among 19 year old big men, and that just hasn’t been the case in the NBA. The Sixers’ perimeter players are frustratingly stagnant when he has the ball, and Okafor hasn’t been looking to pass much. At Duke, Okafor passed out of nearly 30% of his post-up possessions, which is down to under 20% with the Sixers. Pinning down exactly which is the cause and which is the effect is difficult, but I have to believe that somebody who showed such a willingness to pass in college hasn’t all of a sudden become an unwilling passer. There’s so much untapped potential there in terms of how it can help the team).

The problem with the pairing is that the net effect of the two of them together seems to take on the characteristic if the weaker link: the Sixers’ offensive production with both Noel and Okafor on the court is closer to their horrible production with just Noel than it is to their improving production with just Okafor, and the Sixers’ defense with both on the court is closer to their poor rating with just Okafor than it is to their strong rating with just Noel. Neither seems to be able to pick up the other on either end of the court.

But pinning the Sixers’ complete loss of their defensive identity entirely on Okafor’s broad shoulders is unfair as well. In truth, the Sixers began showing this defensive ineptitude last season after they replaced Michael Carter-Williams with Isaiah Canaan, then switched Noel to the power forward spot to accommodate Furkan Aldemir down low.

In fact, the Sixers’ defense was able to withstand one of those two catastrophic changes made late last season. With Noel and Canaan on the court during the second half of the year, but without either Henry Sims or Furkan Aldemir pushing Noel out to the perimeter, the Sixers’ defense gave up just 103.3 points per 100 possessions. But when Aldemir and Noel shared the court, thus pushing Noel away from his greatest strength, the Sixers gave up 116.9 points per 100 possessions. It’s a split that’s starting to look eerily similar to the problems the Sixers are facing by pairing Noel next to Okafor.

(Note: the reason I’m limiting it to after the trade deadline is to try to isolate as few of changes as possible, as changing the Sixers’ perimeter defenders obviously impacts these numbers. It’s also worth looking at what seems like a philosophical shift in the Sixers front office that started at the trade deadline last year, going from long, athletic perimeter players who forced turnovers to shooters who were limited athletically, perhaps hoping to provide space for the post-oriented offense, initially to be designed around Embiid, and later, Okafor. But that’s a topic worthy of a separate post).

| Season | Lineup | Defensive Rating |

|---|---|---|

| 2014-15 | Noel (at center, after MCW trade) | 99.7 |

| 2015-16 | Noel (at center, no Okafor) | 103.8 |

| 2014-15 | Noel (at power forward, after MCW trade) | 113.8 |

| 2015-16 | Noel (at power forward, with Okafor) | 111.8 |

| 2015-16 | Okafor (at center, no Noel) | 112.7 |

For all the grief that Sixers fans, myself included, gave Michael Carter-Williams, he was head and shoulders better than Kendall Marshall or Isaiah Canaan on the defensive side of the court. Still, even with that change the Sixers were able to maintain a strong defensive identity when Noel was at the center position, something which has been true for the most part this year as well.

But with the addition of weak perimeter defenders comes an increased reliance on the team defense provided by big men. It’s here that Okafor, and Aldemir’s, defensive shortcomings stand out like a sore thumb, and Noel’s uniqueness becomes so readily apparent.

“[The defense] has been non-existent lately. We’re getting manhandled physically with adult NBA wings,” Sixers head coach Brett Brown said after losing to the Knicks earlier this week. “We have to guard the perimeter. That has been a challenge, and I think more-so than I expected.

“You combine that with wings right now that are getting overpowered, and then you add Jahlil [Okafor] trying to learn how to defend an NBA pick and roll and have a presence at the rim, and it’s an accumulation of things that end up a problem,” Brown continued.

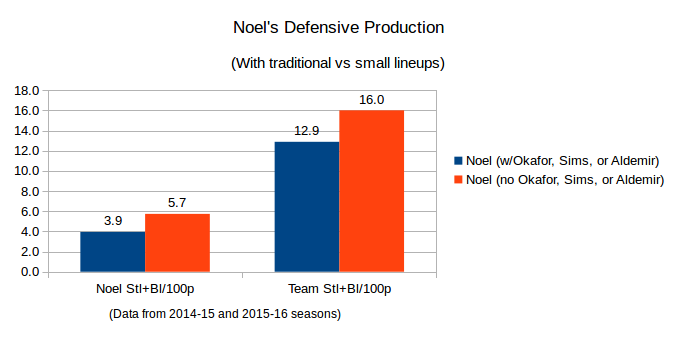

One of the major contributing factors is that when playing with another traditional big man, Nerlens Noel (and the Sixers) just don’t force as many turnovers or generate as many transition opportunities.

(Nerlens Noel’s defensive production over the last two years when paired with another big man. Data as of December 19th, 2015 and courtesy of nba.com/stats)

This impacts both ends of the court for the Sixers. First, it obviously allows the opponent more looks at the basket. And, with less pressure on the point of attack, those looks tend to be quality looks. Second, it limits the transition opportunities the Sixers’ offense can get, which over the years has been a key ingredient in keeping a historically bad offense from completely self destructing.

As I mentioned above, it’s not that the Sixers half-court offense is really worse, it’s more that the Sixers are relying more on their half-court offense than they have at any point of this rebuild. By relying on their half-court offense more, the glaring inadequacies that were always there have become even more self-evident.

Whenever the Sixers pair Noel with another traditional big man, their natural inclination has been to allow Noel to defend the power forward spot. It makes sense, since Noel is so uniquely talented that he can move well enough to defend the perimeter, even if asked to defend smaller, seemingly quicker players. But doing so drastically negates Noel’s defensive impact, a defensive impact which has consistently shown to be capable of anchoring a very good NBA defense if he’s at his natural center position.

What’s interesting is that much of the Sixers’ defensive struggles with Okafor on the court haven’t come as a result of rim protection, but instead from the perimeter. Opponents shoot 36.7% from three point range and 39.2% on shots farther than 16′ from the hoop when Okafor is in the game without Noel, 38.6% and 48.3% when they play together, and just 28.6% and 38.8% when Noel plays alone.

Part of this is likely noise, and could revert back closer to opponent norms, but part of that is also likely a result of the big men’s defensive abilities. Not having an elite shot blocker behind you to clean up mistakes can cause perimeter defenders to sag off more to make a more concerted effort to deny dribble penetration, leaving shooters open. Okafor also plays the pick and roll poorly, giving a ton of room to ball handlers so he can recover back to his man. And when the pair play together, rather than having Noel (elite pick and roll defender for a center) next to, say, Luc Mbah a Moute, another good pick and roll defender, Noel is instead asked to defend guys who are primarily perimeter threats, and it changes his defensive responsibilities in transition to something foreign to him.

The Sixers had evidence this was the case last season, intentionally playing Noel next to Henry Sims and Furkan Aldemir to test the long-term viability of the change.

Of course, to the Sixers’ credit they were experimenting putting Noel next to a traditional big last year in anticipation of Joel Embiid playing basketball. Pulling your best team defender away from where he can make his greatest impact makes a lot more sense if you’re pairing him next to another elite defensive big man, like Embiid projects to be.

Okafor, like Henry Sims and Furkan Aldemir before him, is not an elite defensive prospect. All three are closer to the other end of the spectrum, in fact. The Sixers have one (healthy) big man on the roster with the mobility and help defense capable of transforming this rag-tag bunch of porous perimeter defenders into a competent defensive squad.

“[Defense] has to be an all-game thing,” Nerlens Noel said last week. “Guys have to build that chippiness and toughness that when we do get scored on, we have to feel something. We have to know that’s not right.”

How would Noel, and the defense, look next to another elite defensive big man like Embiid? How much has Noel’s personal struggles, whether that be a result of the nagging injuries he’s sustained, his change in position causing him to hesitate on the court, or just short-term struggles, impact the pairing, and are they destined to improve substantially regardless? Should the Sixers allow Okafor to defend, and struggle, on the perimeter defensively to keep Noel as the last line of defense? Would Okafor’s defense be competent enough if the Sixers’ perimeter defense wasn’t so tragically flawed? Can the Sixers design an offense around Okafor, and other legitimate talent, where these defensive concerns aren’t as grave? Could Noel and Okafor work together with just a couple of two-way perimeter players to complement them?

To me, the biggest problem with the current roster construction of the Sixers isn’t that they are losing games, although doing so at such a historic rate is clearly affecting the morale of the players, management, the fans, and the city. But the real problem is that trying to answer all of these very legitimate questions is difficult in the current situation.

* Note about statistics: all rating stats (offensive rating, defensive rating, net rating) used in this article are from nbawowy.com. This is important because nba.com/stats, basketball-reference, nbawowy, and nba.com/stats play types (synergy) all define possessions differently, mostly a result of how they handle offensive rebounds, which impacts how stats look in comparison to what you may expect. There are two problems with this. First, they can produce drastically different results. For example, the 2014-15 Sixers allowed either 104.8 (basketball-reference), 102.1 (nba.com/stats), or 106.0 (nbawowy) points per 100 possessions last year, depending on who you used. Second, each site has such incredible strengths (basketball-reference for its incredible ability to search for historical data, nba.com/stats for the depth of its SportVU integration, and nbawowy for its ability to filter out lineup combinations) that there are very real situations where each site is the go-to site for data collection. None of this is in itself a problem, and there could be research papers devoted to the merits of each definition for possessions, but the lesson to be learned is this: don’t cross the streams. Flipping between nba.com/stats and nbawowy can paint a picture that is not necessarily there.

* Note #2: All lineup data, with the exception of the opening paragraphs putting the Sixers offensive rating into historical context, from nbawowy.com.

* Note #3: All data, except for won/loss record, was up to, but not including, the Sixers’ December 20th, 2015 game against the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Derek Bodner covers the 76ers for Philadelphia magazine’s new Sixers Post. Follow @DerekBodnerNBA on Twitter.