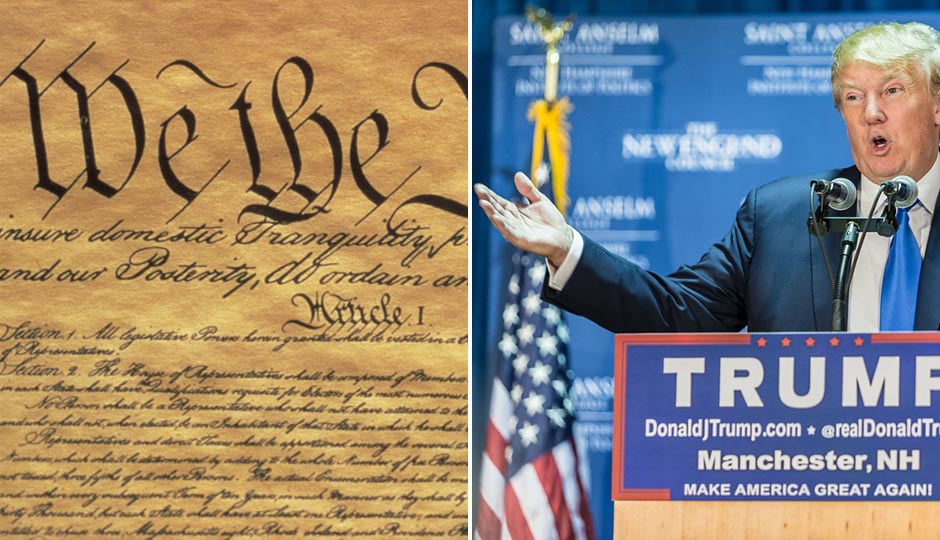

Temple Prof: Donald Trump’s Muslim Ban Is Perfectly Constitutional. Sort Of.

In today’s New York Times, Temple University professor Peter Spiro penned an op-ed delving into the legal nuances of Donald Trump‘s proposal to ban all Muslims from entering the United States of America. We caught up with the Harvard grad at his home to learn more.

The hatred and anti-immigrant paranoia that Donald Trump has been spewing is nothing new, but have you ever seen it or the response to it at this level?

This is shaping up to be a pretty remarkable episode in the sense that you have somebody provoking such intensely critical response and one that crosses the partisan divide at a time when politics are so polarized. That’s what makes this of Constitutional significance. You have an extremely polarized political scene, immigration at the center of that scene — immigration being an issue in which Democrats and Republicans agree on almost nothing — and to have them come together to condemn the Trump proposal, this is evidence of a consensus among political elites that a religious-based test for immigration is just out of bounds.

Out of bounds morally, but Constitutionally valid?

Well, here’s the nuance. It’s not out of bounds Constitutionally as the Constitution has been defined by the courts, but the fact that you have this consensus response condemning the proposal, it evidences that there’s a Constitutional norm that exists outside of the courts which precludes this kind of immigration bar.

So the point here — the higher level point — is that it’s not only the courts that interpret the Constitution, and so even though Trump’s proposal might be consistent with prior precedents of the Supreme Court, it doesn’t necessarily make it Constitutional in the broader sense. The takeaway is that, in a sense, the people are ahead of the courts on this. The court should do a little catching up.

Let’s assume the worst case scenario: Donald Trump wins the nomination and then the presidency and then signs a piece of paper saying no more Muslims. What happens next?

He would have something to work with in Constitutional doctrine as defined by the courts. He could cite cases defending his action. That’s not to say he would win in court, because the courts could catch up with the people. The court can always turn its back on its own precedent.

I feel like there’s a “but” coming.

Well, the courts have been very hands-off when it comes to the regulation of immigration. They don’t scrutinize immigration nearly as closely as regulations in every other area. And so it’s not impossible that a scheme such as this would pass muster where it would never pass muster in any other area.

Why does the court avoid getting involved in immigration issues?

It’s part of a tradition that goes back more than 100 years. It has to do with the ways that immigration is often bound up in foreign policy and national security, and the courts have always been more deferential to presidential actions in these matters. The tradition is pretty well-entrenched through the late 19th Century, and it reached its zenith in the Cold War. The courts just didn’t feel confident enough to review actions relating to immigration. That’s the genesis of this doctrine, and it’s led to some pretty extreme rulings in denying due process to immigrants and upholding classifications that we would never stand for elsewhere.

How extreme?

There was a case in 1952 in which several former members of the Communist Party were deported on the basis of that former membership even though they had been green card holders for several decades and in some cases had renounced their former Communist Party affiliation.

And in another, a case known as Mezei, that involved an individual attempting to enter the United States and who was excluded on the basis of secret information not revealed to him. He was excluded here, no other country would take him, and so he faced the prospect of indefinite detention as a result, and the court upheld that. These are examples where elemental notions of justice have been violated by political branches and tolerated by the courts.

A lot of people are saying, What’s the big deal? Bill Clinton banned Haitians and Jimmy Carter wouldn’t let Iranians in. Is that a useful comparison?

On the one hand, it is. It’s useful to highlight episodes in which immigration law has routinely been decided on the basis of nationality. This is also seen in much more routine ways. If you’re from certain countries, you have an advantage with normal legal immigration. You hear a lot about waiting in line for purposes of legal immigration. The length of that line depends a lot on where you come from.

The Haitian and Iranian examples are more prominent because they involved security or acute immigration-related crises. It’s useful to highlight those.

But the big difference here is that those examples involve a basis of nationality or citizenship, whereas Trump’s plan has as its basis religion. That’s a distinction that is meaningful, and I think most people understand it to be meaningful.

While most of us are appalled at Donald Trump’s proposal, I can understand why it sounds reasonable to some people. After all, the chances of another jihadist attack on U.S. soil are not negligible. What can the government do and what is it doing to prevent terrorists from coming here?

There’s all kinds of vetting that goes on in the visa application process, and to the extent that somebody is in the database or otherwise raises red flags, there is a security apparatus in place to I.D. those individuals.

The most vulnerable portal in enforcement is the Visa Waiver Program, under which nationals of more than three dozen countries can enter for business or tourism without a visa. You get the Paris shooter with EU citizenship — they have an easier way in because they don’t have to apply for a visa. But Congress is about to enact some new controls on that program. They are taking steps to tighten up on that and make it better adapted to the security environment.

The other side of this is that one has to be aware that having foreigners coming into the United States is a huge economic plus, and to the extent that you restrict travel and make it more difficult to come here, there are really big economic costs indicated.

Peter Spiro is the Charles R. Weiner Professor of Law at Temple University’s Beasley School of Law.

Follow @VictorFiorillo on Twitter.