Allan Domb: The Condo King

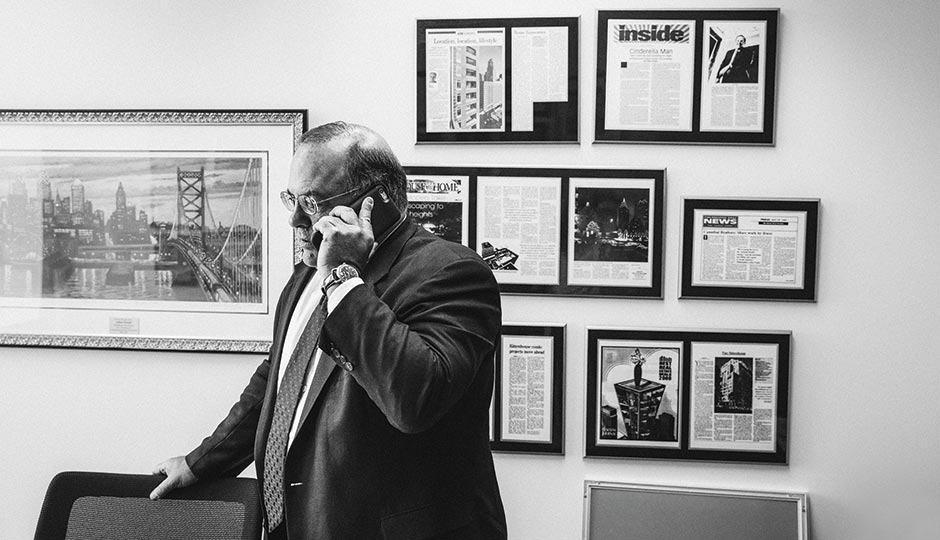

Allan Domb in his Rittenhouse Square office. Photograph by Colin Lenton

There are two distraught gentlemen in Allan Domb’s lobby, flipping out about the Pope. The date is July 29th, almost two months before Francis and a million of his admirers are to plunge the City of Philadelphia into holy sacramental chaos. Domb’s visitors are emissaries from the restaurant world, here to bang warning gongs about the culinary gridlock they foresee: marooned employees, bewildered customers, spoiled meat.

“There doesn’t seem to be a strategic plan at all. Just, ‘Hey, you guys are fucked.’” This is Greg Dodge, manager of the wine bar Zavino. Either Greg’s face is really tanned or all the blood has rushed to his head. He’s wearing one of those shirts where the collar is white but everything else is blue. “It just doesn’t make any sense.”

“You said there doesn’t seem to be a strategic plan,” adds Jeff Benjamin. Benjamin is the chief operating officer of Vetri. Bald and a little angular, he kind of looks like Vetri, the man. “There isn’t a strategic plan.”

Dodge begins to pick up steam. “Can you imagine, hypothetically, New York saying the same thing to its business owners?” he asks. “They would kill them!” Gripped by some sort of Armageddon fever, Dodge continues, his voice rising and falling uncontrollably. His rant culminates in a shake of the head. “It’s insane,” he whispers. “It’s insane.”

Eventually, Domb strides into the lobby to scoop us up. We file into a conference room, where Dodge explains why they’ve come to him to seek “clarity” on the city’s papal game plan: “I think you’re the best singular voice to get someone to say, ‘We’re not going to do shit — figure it out’ or ‘Yes we can, absolutely.’”

Allan Domb, since he landed in Philadelphia in the late 1970s, has been the guy who sells you your Rittenhouse condo. Then, last spring, to everyone’s great surprise, he decided to run for City Council, handily winning the Democratic nomination for an at-large seat after pouring a million dollars of his own money into the campaign. He was armed with a lot of cash and zero political experience, and nobody was entirely sure what he was doing. Conspiracy theories burbled. Rumors of an eventual mayoral run swirled. Close friends were perplexed. “All of a sudden I heard him talking about running for office,” says his lawyer, business partner and all-purpose consigliere, Paul Rosen, “and I said, ‘Allan, are you crazy?’”

The fish-out-of-water imagery, on one hand, adds to the general sense of absurdity that has accompanied the Condo King’s candidacy. It’s difficult to imagine Domb, C-Suite business exec, trapped behind a cramped desk in City Council chambers as his colleagues debate, say, 3-D billboard legislation. On the other hand, it’s precisely his odd new mix of business savvy and political power that has apparently made him the go-to guy to solve the looming papal meltdown.

Back in the conference room, Domb, who’s 60, appears calm. His 22nd-story view points south, past the two restaurateurs across the table, toward the stadiums and the refineries. He picks up his cell phone and calls Paul Levy, CEO of the Center City District. Levy doesn’t answer. Next he tries Joe Grace, director of public policy for the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce. No luck there, either. Finally, Domb’s chief political aide brings him a Post-it note bearing the cell-phone number of Congressman Bob Brady. Domb dials twice, gets no answer, and gives up.

Eventually he just calls City Hall’s main number and presses buttons until he gets to an employee named Robert Allen, who quickly depletes himself of information and directs Domb to another city employee. After Robert Allen hangs up, Dodge and Benjamin rise to leave. If either of them is upset that close to nothing has been accomplished today, it isn’t evident. Suddenly, both of them seem quite Zen.

I ask Domb for his assessment of the city’s preparedness. He smiles wanly. “I have faith.”

Jeff Benjamin, halfway out the door, tacks on a postscript: “I have faith in Allan.”

AS BEST AS I can tell, the two most powerful real estate moguls currently running for political office in America are named Donald Trump and Allan Domb. In pretty much every respect — grasp of complex issues, size of personality, propensity for casual misogyny — the two occupy opposite sides of the spectrum. The mere mention of Trump already seems to be cheapening this story, but it’s worth dwelling on one more dissimilarity. While Trump’s presidential run has horrified the nation’s political establishment, Domb, whose victory in November’s general election is all but assured, has been welcomed as nothing short of a savior.

When I surveyed the city’s power elite, everyone said the same thing. The only variation was in how much they love Allan Domb.

Joe Zuritsky, CEO, Parkway Corporation: “Allan is a force of nature. He is a laser beam. I can’t think of anyone I’d rather have on City Council.”

Jerry Sweeney, president and CEO, Brandywine Realty Trust: “I think the world of Allan Domb. I think he’ll challenge the status quo, but challenge it in a very constructive, positive, productive way.”

Walt D’Alessio, principal, NorthMarq Advisors: “Let’s do a statue of him or something.”

Why the Domb worship? Loyal friend, man of integrity, straight shooter. The characterological aspect isn’t to be discounted. But the more straightforward reason is that he built up a wildly successful business empire from scratch, without any special political or nepotistic advantage, and without pissing off too many people, either. Given the clubby parochialism that tends to govern this city’s biz-dev orbit, it’s impressive that Domb, a working-class kid from Fort Lee, New Jersey, arrived here in his 20s to work for a lock company, only to singlehandedly build up and corner an entire subset of the city’s real estate market.

They call him the Condo King because while he does advertise — including, often, on the back page of this magazine — he really doesn’t need to. It’s accepted wisdom by now that he controls roughly 75 percent of the luxury condominium market. “If you’re going to buy a condo in Philadelphia, why not go to the most knowledgeable person?” asks Michael Cohen, a prominent (but not Domb-prominent) Philly realtor. “If you want your best bang for your buck, why not call the best guy?”

(It’s difficult to know exactly how much Allan Domb Real Estate’s brokerage business makes in a year. The last time he told a reporter, in 2007, he said his office brought in $200 million in annual sales.)

But to focus on Domb’s condominium sultanate somewhat misses the point. Quietly, he’s also bought a lot of the city’s real estate, much of it around Rittenhouse Square. The Beaux Arts Anthropologie mansion on the corner of 18th and Walnut? His. The Barnes & Noble building next door? Also his. Barneys Co-Op? Devon? Parc? Barclay Prime? He owns all of that space and much more.

Speaking of which, there’s yet another aspect of Domb’s career — perhaps the most significant, least-remarked-upon aspect — that merits attention. Roughly a decade ago, Domb seeded a substantial sum of money to restaurant impresario Stephen Starr in exchange for a stake in his business. (Two sources put that number at 42 percent, which Starr and Domb would neither confirm nor deny.) “He owns a fairly significant part,” Starr says of Domb’s share of his 31-restaurant empire. “But I’m not going to tell you the percentage he owns.”

All this is to say: Between the offices and the condos and the steakhouses and the martini bars, Domb isn’t just a successful realtor; he’s one of the most dominant business figures in Philadelphia. And given the sheer amount of city business that could affect his income streams, he’s on the brink of what might be his most valuable land grab yet: an office in City Hall.

Which is where things begin to get interesting. Domb’s reputation, stellar though it may be, wasn’t earned through a deep commitment to public service. Until this year, “giving back” meant being president (briefly) of the Friends of Rittenhouse Square. Over the past decade, he’s only voted in about half the city’s elections. And yet the Jerry Sweeneys, the Joe Zuritskys, the Jeff Benjamins, surveying all that is broken with Philadelphia, turning to Allan Domb to fix it, they have faith.

Should they?

THE DAY BEFORE he’s enlisted into papal crisis management, Domb walks from his office, on the north end of Rittenhouse Square, to the Dorchester, on the west end of Rittenhouse Square, for a showing with a couple of empty nesters from Wynnewood. (Prime treetop view, balcony: $1.3 million.) Afterward, Domb and I head downstairs, where we’re greeted by a summer rainstorm. Taking shelter alongside us are two bike cops in shorts and sneakers.

“Are you able to catch people better on a bike?” Domb asks one of them.

“Yeah,” says the bike cop.

“I’m trying to visualize it,” Domb continues. “The guy’s running. You’re on the bike. Are you, like, vaulting yourself off the bike?”

“If I know I can catch up to him,” answers Bike Cop. “Every situation’s unique.”

The encounter goes on like this for another 10 minutes or so. It’s perfectly pleasant — topics include the state of public education and the townhouse that developer Bart Blatstein is revamping for himself next door — but also bizarre, because Domb never thinks to reveal himself as a candidate for political office. Selling condos, easy. Selling himself, harder.

Squirming, I break through a sort of fourth wall and do it for him. One of his campaign posters is plastered to the window of Bella Medspa, the Botox joint 10 yards away from us. I point to it and ask the cops if they recognize the mug. “This guy’s a troublemaker,” Domb says, uncomfortably. Then, finally, “I’m running for Council.”

Domb doesn’t cut the figure of a typical politician. He’s a little heavyset and kind of bald; his outfits tempt you into writing “nondescript” in your notebook in lieu of actually describing them. But then, he’s not a typical politician. Nothing in the past six decades of his life really prepared him for his new avocation. Domb was born in Jersey City; his father and his father’s father, a Polish immigrant, worked in the embroidery business. Domb, whose actual first name is Michael and whose middle name is Allan, began shining shoes at age four — the first in an endless, Tom Sawyer-esque string of odd jobs.

After college at American University, Domb landed a job as the general manager of Phelps Time Lock, a Philly-based company that, well, installed locks. The real estate thing, meanwhile, happened almost by accident. “Remember Winston’s? Fifteenth and Locust. Burger place,” he reminisces. “I was going to work four nights a week, seven to midnight, as a waiter. Then I heard this guy on the radio, Jay Lamont, talking about real estate.” For three years, he worked two jobs — one at the lock place, the other selling condos. In 1982, he was named the top residential broker in Philadelphia. Four years later, he was being recognized as the number one realtor in the country.

Allan Domb’s secret to success isn’t really a secret, since he and every other realtor in town will tell it to you. “I read a book in 1979 by Glen Gardner,” he says during an interview in his conference room, distilling his business philosophy. “It was How I Sold A Million Dollars Worth of Real Estate in One Year. And it said in the book: Become a one-street specialist, just like the best doctors and best lawyers and best whatever.” So he picked Rittenhouse and he picked condos, and the rest is a bunch of real estate trophies.

There were other, smaller factors, of course. Joanne Davidow, another longtime Rittenhouse specialist, points out that Domb was one of the first realtors in Philadelphia to start listing the square footage of his apartments. Another is that by virtue of owning so much property, he managed to sit on the boards of the condominium buildings for which he also serves as a broker. Which allows him, as realtor David Snyder puts it, “to keep his finger on the pulse” of the buildings.

(Not that his touch is always the lightest. Steven Sheller, an attorney who bought a condo from Domb in the Parc Rittenhouse, has been embroiled in litigation with him for two years, alleging he violated the terms of their agreement by — among other things — trying to put a hotel in the building. That hotel never got built. Domb, through his spokesman, Dan Fee, declined to comment on the litigation, which is ongoing.)

Perhaps the most salient factor that explains the Condo King’s market dominance, though, is the one that sounds most trite: his work ethic. For all the dubious, triumphalist business success stories you hear about CEOs who sleep seven minutes a night and proudly neglect their children, Domb might actually be the rare guy who happily never stops working. “He sleeps maybe four hours a night — maybe,” says one former colleague who didn’t want Domb to know she was speaking to the press. “He takes home bags of information every night. Then I would get emails at 2 a.m., and then again at 6 a.m.”

Which is why despite his mastery of the Square, despite living and working and generally knowing every spec about every condo on the Square, Allan Domb isn’t really of the Square. “I don’t see him at anything,” says Pennsylvania Council on the Arts chair and woman-about-Rittenhouse Diane Dalto Woosnam. “He doesn’t attend any of the charity functions. I don’t see him at arts events. I don’t even see him out to dinner.” Adds entrepreneur and Square denizen Joe Weiss, who contributed to his campaign, “He’s totally been immersed in his thing. I never saw a lot of big contributions anywhere. You don’t see his name on anything. Except for his signs.”

(While we’re on the topic of Allan Domb’s personal life, or lack thereof: He’s twice married and twice divorced. His second wife, Carol, is the superintendent of the Girard Academic Music Program, a public magnet school in South Philadelphia.)

Domb’s real estate monomania, ironically, may explain his sudden interest in politics. For the past three years, Domb has served as president of the Greater Philadelphia Association of Realtors (GPAR), which under his leadership was transformed from a sleepy advocacy shop to a well-oiled lobbying machine. “The board has never been so effective in the 30 years I’ve been involved,” says realtor Mike McCann, Domb’s only true rival for brokerage supremacy in Philadelphia. “Now the city contacts us before they’re going to change something.” Much of the high-profile real estate policy enacted during Domb’s term — the Actual Value Initiative, the creation of the land bank, the selling-off of shuttered school buildings — GPAR advocated for.

Still, that Domb has volunteered to spend his days toiling for a notoriously plodding and hidebound institution (and he will be volunteering, as he’s vowed to donate his salary to the School District of Philadelphia) remains baffling to the city’s political class. “Half the people wonder if he’s just going to sit in his office and twiddle his thumbs, or just not be there at all,” says campaign consultant Michael Bronstein. “If you’re worth that much money and you’re sitting around in an office and have no tolerance for the bullshit, how long can you sit there?”

There were some out-there theories (e.g., City Council president Darrell Clarke convinced Domb to run so that he’d spend a lot of money and trip the city’s “millionaire provision,” allowing Clarke’s buddies to spend more money on their own races), and there were some less out-there theories (e.g., Domb sees Council as a career stepping stone). “He did want to run for mayor. He told me he wanted to,” says political strategist Larry Ceisler. “I think he was playing with the idea of running as a Republican.” (Domb confirms he flirted with a mayoral run “for a New York minute.”)

Whatever his precise motivations, Domb was intent enough on getting elected that he dropped just over a million dollars of his own money into the race (unheard-of in a Council election), most of it spent on television ads. To bolster his nonexistent ground game, he hired John Sabatina Sr., the powerful Northeast Philly ward leader, to garner support in parts of the city where he had rarely if ever set foot. His investments were rewarded: In May, he secured one of the five available Democratic at-large Council slots.

Last spring, financier Arthur Birenbaum hosted a fund-raiser for Domb. Heavy on statistics and light on anything else, Domb’s speech that night was, in the words of one attendee, “deadly.” But at least there were statistics. Whatever his shortcomings as a retail politician, Domb possesses a wonkishness that most of his new Council colleagues decidedly lack. Furthermore, his Mike Bloomberg-inspired plot to collect $1.6 billion in delinquent property taxes — the centerpiece of his agenda — rests squarely in his wheelhouse.

In this way, one can see how Domb might wind up a productive legislator — not thanks to some vague entrepreneurial juju, but by being exactly what he’s been for the past 35 years: a wealthy, data-driven real estate magnate. “The level of information on which major decisions is made is often very limited,” says Paul Levy. Domb, thanks to his mind-set and maybe even his wallet, is poised to shake things up: “Allan has the means to say, ‘Let’s just commission a study. How’s New York doing? How’s Boston doing?’ Philadelphia often tends to be inward-looking.”

Still, one can get the sense that Domb, cocooned in his Rittenhouse safe space, is dangerously abstracted from the city that’s enlisted him into service. Domb’s actual reason for running, according to him, came by way of an epiphany. “I took a Saturday and Sunday and drove to all 26 [closed] schools, all over the city, from Southwest Philadelphia to the Fairhill [Elementary] School in Juniata,” Domb says. (Technically, 24 schools were closed.) “And I saw sections of the city and I said, ‘Wow, this is not good.’ And I said, ‘You know what, these areas need major help.’ And I said to myself, ‘This is an opportunity if I ever want to make a change, that you could really help these areas.’”

Domb’s anti-poverty agenda, likewise, is at once well intentioned and naive. The centerpiece is to increase public awareness of the Earned Income Tax Credit, a federal program for the working poor. Each year, an estimated 40,000 Philadelphians fail to sign up for the EITC’s average $2,500 credit. Given the zealous way Domb talks about his EITC plan, though, one gets the distinct impression he had never heard of the 40-year-old program until recently. And that he’s not aware that in January of 2015, the City of Philadelphia began mandating that businesses notify employees of the EITC program.

Toward the end of our interview in his office, Domb, defending the 80-hour workweeks he plans to maintain (40 hours of Council, 40 hours of condos), asserts that “if you don’t have a passion for something, you’re not going to be good at it.”

I ask him if his passion, then, is real estate or politics.

“My passion’s helping people,” he replies.

I point out that condo buyers aren’t exactly a good representation of his new 1.4 million-person constituency.

“You know,” he replies, without a hint of irony, “I do rentals, too.”

IN ANOTHER CITY, if a wealthy man with no political experience bought himself a ticket to elected office, skepticism might be on higher alert. But in Philadelphia, the absence of competent business-savvy leadership is so pronounced that Domb’s occasional political dyslexia may, in a Trump-like way, seem a perverse asset.

The most prominent businessman-cum-politician to serve Philadelphia was surely former Councilman Thacher Longstreth. The late Thatch — he of the Mayflower descent, Quaker temperament and WASP affectation — seemed like the kind of guy who lived off quietly inherited wealth. While he had some of that, he also worked as an executive at Philly’s Aitken-Kynett ad agency, before helming — and reviving — the once-moribund Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce.

After Thatch, examples are harder to come by. There’s Tom Knox, the insurance magnate who worked briefly and vaguely in Ed Rendell’s mayoral administration before self-funding his way to a second-place finish in the 2007 Democratic mayoral primary. There’s Comcast’s David L. Cohen, whose business career largely postdates his position as Rendell’s right-hand man. And then there are the Rizzocrats of a certain age who have spent their careers hovering in a sort of public-private ether: WHYY president and CEO Bill Marrazzo, ex-Tastykake boss Charlie Pizzi, former PIDC chairman Walt D’Alessio.

For the most part, though, we’re talking about even lesser businessmen: restaurant owners like convicted felon and former City Councilman Jimmy Tayoun, or people with mysterious jobs at random Center City businesses, like mayor-to-be Jim Kenney, who long held a $75,000-a-year consulting gig with architecture firm Vitetta.

Domb is in a different class. Comparing Domb to former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, Paul Levy makes the point that Domb “is not beholden to a lot of traditional fund-raising needs.” But Domb’s not exactly a free agent, either. Bloomberg, as mayor, stepped down from the helm of Bloomberg LP, his media-and-financial-data behemoth. Domb isn’t stepping down from Allan Domb Real Estate or from Starr Restaurants (though he says he may aim for “smaller” development deals now). Besides, Bloomberg’s business empire didn’t affect New York City to the same degree that Domb’s affects Philadelphia’s. “It’s not like he’s a [venture capitalist], making investments all over the world,” Committee of Seventy president and CEO David Thornburgh says of Domb. “His core business is a locally influenced and regulated activity.”

None of Domb’s chief political proposals — public-school partnerships with local businesses, pension reform, tax collection — scream conflict-of-interest. But it’s worth noting that he first came to the tax delinquency issue through GPAR, as a way for the city to raise revenue without also raising property taxes. Point is: A wide swath of public policy, no matter how well-intentioned, could affect the bottom line of Allan Domb Real Estate. “Realtors or developers care about City Hall more than almost any type of person you can think of,” says Wojdak & Associates lobbyist John Hawkins. “If City Hall’s politics aren’t conducive to growth, it’s the realtors or developers who pay the price.”

Same goes for Domb’s food-and-drink interests. (In addition to Starr Restaurants, he’s also an investor in HipCityVeg and Charlie Was a Sinner.) In his victory speech at Smith & Wollensky last spring, Domb said he’d come around to the necessity of a $10.10 minimum wage and eventually convinced a skeptical Starr. “I think it should be raised,” Starr told me. “But I think it should be raised intelligently.” Nothing wrong with that, of course. But what if Starr is the more persuasive one next time?

The issue isn’t so much that Domb is a serially unethical operator — by all accounts, he isn’t. It’s that his holdings are so vast, it may actually be impossible for him to completely segregate city business and personal business. Between the condos, restaurants and buildings Domb has a stake in, there are more than 550 separate sources of income listed on the statement of financial interest he filed with the Board of Ethics. “The first thing that strikes me is how unusual the circumstance is,” says Thornburgh. “This is a test of him and a test of the system.”

The first test the Domb campaign faced, at least with respect to this article, didn’t go particularly smoothly. Domb’s media consultant and spokesman, Fee, initially resisted giving me access to his client, offering a two-pronged explanation. If the piece was positive, Domb worried, readers would think he bought himself good press with his Philly Mag advertisements. If it was negative, his business partners might just decide to pull their support from the magazine. For a candidate vowing to keep a firewall between his political career and business interests, this was an inauspicious start.

Domb seems earnestly interested in abiding by the guidelines set by the Philadelphia Board of Ethics. Problem is, those guidelines are fairly weak. According to the BOE — bear with us here — a politician must recuse himself from a vote if it directly affects him or one of his family members. Nobody seems quite sure what “directly” means, though. A bill proposing to tax the Continental Midtown for being hopelessly un-hip and past its prime: Domb would presumably need to recuse himself. A citywide bill on health care or wages that would affect all of the Continental’s employees: Domb is presumably free to vote.

Philadelphia’s fate won’t hang in the balance of narrow questions like these. But they do get at the broader concerns that arise when a titan of industry — well, insofar as Philadelphia has titans of industry — rides into office on a wave of his own cash and then gives you a puzzled look when you ask him if he’ll be stepping down in any

way from his moneymaking enterprises.

MY LAST MEETING with Domb is at Parc, where he’s the landlord. Fee orders a tomato salad. Domb orders the same, plus grilled chicken. While they eat, I raise some questions about how Domb’s self-funded candidacy and general wealth square with his new mandate to serve the entire City of Philadelphia.

“Let me say this about the money,” Domb says, placidly. “I think we raised about $450,000, $475,000, from other people. … And I spent minimal time doing it. Minimal. Because for me, I was working. I actually feel if I had spent the normal time, it would have been more than double that.” (Actually, Domb raised about $550,000, from the likes of Wayne Kimmel, Joan Shepp, Michael Solomonov, Richard Vague, Janet Haas, Judee von Seldenick and other Philly VIPs.)

If this disquisition on fund-raising is meant to suggest that Domb might have won without the aid of his own checking account, his next comment is meant to remind me what all this money is ultimately meant to serve.

“I feel like I invested the money to help the city,” he says. “There’s no gain for me to do this. The gain is, I want to help the city, collect those taxes. Let me say this, if I can help take a hundred thousand people out of poverty, and I can clean up and collect $1.6 billion in the next four years, I’ll be very happy.”

Fee, a practitioner of realpolitik, tends to veer away from wildly optimistic projections. Instead, he fends off my line of questioning with a different approach: “Let me ask you a question, separate from whatever he’s going to say. Do you believe the current system is democratic? In this city? Would you describe that as little-‘d’ democratic?”

Fee’s timing is good. A day earlier, Congressman Chaka Fattah was charged with racketeering, bribery, money laundering, filing false statements and fraud.

For Domb to be soiling Philadelphia’s democratic values, Fee says, “Well, you have to presume that they were democratic to start with.”

A few minutes later, Allan Domb gets up, shakes my hand, and takes a 0.1-mile walk to his office, back through Rittenhouse Square.

Published as “The Condo King” in the October 2015 issue of Philadelphia magazine.