What Happened After My Kidnapping

Photography by Theresa Stigale. Assistant photographer: Judy Murray

Hello, my name is Brad Pearson. In March 2006, you were one of three people who kidnapped me in West Philadelphia.

I’m writing this letter not because I’m angry at you, or upset, or hurt. The opposite, actually. While the kidnapping and investigation were difficult for me, in the end they made me a stronger man.

I’m a magazine writer now, and I’ve always hoped to talk to you and Jerry and Mordi about that night, and what your lives have been like since. I’d either like to do that by letter or in person. I can travel to Pennsylvania to speak with you, if you’d allow me to. I also included my email address, if that’s easier for you.

Again, I’m not angry, and I’d really just like to talk.

Sincerely,

Brad Pearson

Jerry’s response came first, less than a month later. Two pages, handwritten, single-spaced. All-caps block letters, except for the words “Sincerely, Jerry Price,” in cursive:

In your letter, you said ‘I don’t know if you remember.’ The truth is that I don’t think that I will ever be able to forget you. That day — your face plays over and over in my head constantly reminding me of the hurt, anger, sorrow and other feelings that I have caused you as well as the others.

Tyree soon sent a letter, too: “Being a dad in jail is really sad.”

I started looking at flights.

Photography by Theresa Stigale. Assistant photographer: Judy Murray

THE WEATHER WAS unseasonably warm that night, but I still needed a coat. It was a little after 10 p.m., and I’d parked at the corner of 58th Street and Overbrook Avenue, two blocks off St. Joe’s campus.

As I made my way down the street, the silver tips of my sneakers reflected each street lamp. A few steps after I turned onto Overbrook, though, the shine stopped, signaling the end of the area the school actually cared about. Shattered glass covered the leaves in the gutter, a reminder that someone probably left an iPod in a cup holder.

I hopped over the broken glass, and two men approached. They chatted and laughed; neither of them looked at me.

My car sat 20 steps ahead. As I turned the corner, I heard the first noise. Smack, smack, smack, rubber on concrete. Then grrick, grrick, grrick, rubber on gravel. Whooosh as jacket grazed cedars.

“Don’t fucking look at me. Look at the fucking ground.”

There was another whoosh, and the light bounced off a pistol now pointed at my head. I couldn’t concentrate on the weapon; the man’s voice was puerile. He was like a baby holding a shiny toy. He grabbed my arm and pushed me out of the street’s light, next to a sinking Ford Escort outside a rotting garage. The wooden door was a pile of paint and beetle bore creeping toward the expired license plates.

“Empty out your pockets.”

I tossed to the ground the contents of my hands: car key, water bottle. Cell phone and wallet were next.

“Is that all you got?”

They quickly reached into my pockets to confirm my response.

“You got an ATM card?”

Yes, I said, it’s Wachovia but says First Union, it’s green. Sir. Yes, I have my ATM card, sir.

“Don’t call me FUCKING sir, that shit’s for white people. What’s the PIN number for your MAC card?”

Now, what’s the play here? Correct number, they leave and I walk away? Wrong number, they leave, they have my wallet and find me after they realize the number is bunk?

“One four six six.”

“Why the fuck should we believe you?”

“I swear to God that’s the number. I wouldn’t lie to you.”

Normal Brad would have lied to them. Gun-to-head Brad thinks differently.

“We’re going for a ride.”

They grabbed me by the back of the neck. My head popped up for a split second.

“Keep your fucking head down. You look up again and I will shoot you in the fucking face.”

My chin dove into my collarbone, and they threw me toward a running car. Dark paint, tan leather interior. I hit my head on the door frame, my two attackers flanked me on either side, and we were off. A third man drove.

“How much money do you have in the account?”

We’d driven straight for a few blocks, then hung a right and a sharp left. My mental GPS slowed down as we drove farther and farther, as more turns stacked on backtracks. Was that a turn or a curve?

“About $800, I think.”

“If there is one dime less than $800 in your account, I will shoot you in the fucking face. Do you understand?”

The possibility of a delay between my cashing of a check and that money’s appearance in my account seemed plausible, so in an abundance of caution, I told them there might only be $600.

“Oh, so you lied to us. My associates and I don’t like liars, Brad. You know what else we don’t like? Heroes. So don’t try to be a fucking hero, Brad, or I’ll have to shoot you.”

In the fucking face. Got it. After the lesson in fiscal responsibility, the man to my right began to talk. And talk. He asked if I’d handed in a paper I was working on. He asked how my job was. He asked if I saw a kid on campus with black hair. He tried to convince me that they had been following me for weeks.

The car stopped, and one of the men exited. A second later, he was back. Place didn’t have an ATM, he complained, and we returned to the road. They were novices, kids with higher voices than mine, and they didn’t know where to find an ATM.

“WHO’S ‘ADO,’ BRAD?”

When I was a baby, my parents and I lived in my grandparents’ attic. The three of us would wander downstairs each morning, where my grandmother would place me on her lap.

“I do love you! I do love you!” she’d say. “I do” became “Ado,” and the name stuck to her.

I winced. He’d begun scrolling through my phone, and Ado is my first contact.

“Home.”

As he made his way through my alphabet of contacts, I answered each query with one of three responses: home, college or work. At 21, those are the only three options anyone really has.

But … Ado. For the first time, I thought of my family — my dad, my mom, my brothers and my sister. At home, all of them, asleep, unworried.

“Do you have a girlfriend, Brad?”

Lie, just lie, don’t think about it just lie. Kelleen’s face filled the backs of my eyelids, her hair and her dimples. She turned and smiled, all gauzy movie sequence.

“No, I don’t.”

Photography by Theresa Stigale. Assistant photographer: Judy Murray

“STAY THE FUCK DOWN, Braddy Brad.”

In the short trip, I’d acquired a nickname, and we finally pulled up to an ATM. One of the men left and returned again quickly.

“We got out $700.”

“I thought you said there was going to be $800, Brad.”

I stammered out an excuse revolving around the American banking system, but the subtext was please don’t kill me please don’t kill me please don’t kill me over $100.

“All right, 700 bucks, divide that shit up.”

“Twenty 40 60 80 100 20 40 60 … yo, I think we got enough.”

We left to score some coke.

Burst. Stop. Burst. Stop. Long burst, quick body-throwing stop. The window lowered, and a man stepped up.

“Yo, who the fuck is that?”

“Quiet down, you want us to get caught?”

Money was exchanged, coke was scored. The door seemed close. I could kick it open and run. I could run faster than they could. I had adrenaline on my side, I had fear on my side, I had living on my side. But I didn’t have a gun on my side. The pistol rested over my left shoulder, warmed by his hand and my shoulder. My head wedged between my knees. I stayed.

Cramped, I moved the fingers on one hand, pinkie to thumb, thumb to pinkie, an imprisoned pianist. Silence, so I worked the other hand.

“Brad, if you move one more time, I swear to God I’ll fucking kill you. I haven’t killed anyone in a few months, Brad, and I’m getting kinda anxious.”

Before, I had been convinced they would let me go; now, I wasn’t so sure. It would be a quick death, hopefully. One shot, right to the head. They’d get their $700, and someone walking his dog would find me, without a wallet or forehead.

“Sometimes I like to use a knife, Brad, right across the throat. Slittttttt.”

Flipping through my wallet, he passed over a stack of Pathmark SuperSaver cards and expired Papa John’s coupons, settling on my Eagle Scout card. Matte gold.

“I see you’re also an Eagle Scout.”

The emphasis fell on also instead of “an Eagle Scout.” Brothers in arms, it seemed.

We talked about Hawk Mountain, a rounded-off lump of a Pennsylvania peak that he encouraged me to visit. Any comfort I gleaned from the conversation died quickly as they spotted a police car. The psychology of telling me about the car was twisted, but I may have given them too much credit. A fucking shot to the face was once again promised, heroism again discouraged. I stayed in my crouch, Jay-Z’s Reasonable Doubt was once again turned up, and we continued on.

“YO, MAN, LET’S LET BRAD GO.”

The suggestion came from one of my original abductors. They were the first words he’d said since he’d doled out the cash. I was asked if I’d like to be dropped off anywhere in particular, a sort of forced chauffeur service. Literally anywhere, I said.

“You don’t want us to drop you off anywhere, Brad. Your ass will end up raped and naked in the streets.”

Laughter filled the car, and I joined in. I’m free! Let’s all laugh about how great the past hour has been! I don’t know why I laughed. Maybe it was just that I hadn’t been told I’d be shot in the fucking face for a few minutes, and to me, that seemed like a reason to celebrate.

They pulled over and grabbed me from the left side, dragging me out of the backseat. I tripped on the curb, then some sticks, and slipped on the grass and a piece of wet cardboard. My face was covered and down; fresh air filled me. I slowed, and felt the brush at my knees.

“Lay the fuck down.”

The decomposing leaves smelled clean somehow, and my nose burrowed into them. One of the men told me to count to 100 and made me promise not to go to the police. Do not run home, either: Walk. Do not jog: Walk. I began counting.

One.

Two.

Three.

Four.

Five.

Six.

Seven.

The gun cocked over my head.

I tried counting to eight, but all I could hear was the hammer sliding, the click-clack of a roller coaster approaching the top of a hill.

I waited to die, and I prayed.

Dear God don’t let this happen dear God I can’t die dear God help me help me live help me see my family help me see Kelleen help me live I need to live. I hadn’t been to church without parental nudging in my entire life. Whatever goodwill I had stored up during those trips was already cashed in.

“Don’t fucking move. … ”

“Just keep counting.”

Eight.

Nine.

Ten.

Eleven.

I counted to 200, maybe 500. Exhausted, I almost fell asleep. When I finally stood up and opened my eyes, I thought I was back at 58th and Overbrook. Trees surrounded me, and a cedar stood at my left once again. I had no idea where I was.

Walletless, phoneless, I crossed an abandoned lot and headed for the street. Two blocks up, I ran into a man. Black and wiry, with a wispy, graying goatee.

“What are you doing here?”

“I need to find my way home.”

SOON, THE POLICE picked up Jerry Price, Tyree Brown and Mordi Baskerville — not just for my kidnapping, but for 12 other kidnappings and robberies across West Philadelphia. They’d started showing up at Price’s cousin’s apartment with cash, cell phones, a Lexus and pizza. (In addition to college students, the three also robbed pizza deliverymen. And why waste a good pizza?) Laptops and wallets arrived at the Parkside apartment, too.

During the pretrial hearings, the three smirked as they sat at the defendants’ table. One by one we entered the courtroom and talked about getting pistol-whipped or mock-executed or otherwise embarrassed. My dad and girlfriend sat in the audience. When my dad would get upset, Kelleen would take his hand.

The night before the trial was set to begin, they all pleaded guilty. Mordi, the youngest at 16, flipped first. In exchange, a lighter sentence of seven to 15 years. Jerry, who was 17, got nine to 18. Tyree, age 18, 10 to 20.

In the weeks and months following the kidnapping, I lived off free rail drinks and well-wishes, cocky and alive. Then I went back to my apartment and had nightmares. The room would be dark, beyond vision. There was something in there, ready to attack. Or maybe there was nothing in the room and I just had my eyes closed, afraid to open them. I’d always wake up before I found out.

I cried once, on my parents’ deck in New York. I yelled into the phone at Kelleen, blaming Jerry, Tyree and Mordi for my inability to land a job after graduation. But it wasn’t true. I blamed them, sure, but I could have gotten a job. It was easy to deflect.

That first year passed. Jerry, Tyree and Mordi went to jail, and I slowly climbed back into life. I got a job. I moved to Maryland, and then eventually Texas. I’d think about them, 1,500 miles away in prison, whenever I’d get a victim compensation check from one of my kidnappers: a few dollars here and there to pay for my missing wallet, cell phone and bank fees. My mom would get the checks in New York, then forward them to wherever I was living. I’d take the check, say “Fuck you” out loud, and slide it into an accordion folder. They’re still there now, $78.22 worth, at the bottom of my closet.

The kidnapping became a crutch, too, one I would break out especially during job interviews. My favorite question was, “Tell us about a time you overcame adversity.” I had them then. (It worked two out of the three times I tried it.) I knew I had the best party story, the best sob story, the best any story. A psychiatrist could diagnose this behavior: Coping through manipulative bragging. If I’d gone to more than one session, maybe mine would have.

March 27th was always an awkward day, one I wasn’t sure whether to celebrate or forget. Eventually March would flip to April without my notice. But something still lingered in the back of my head. What were they doing? Were they thinking about me? Did they care? Do I care?

Kelleen and I got married; we got a dog. Then, last summer, I sat down and typed two short letters to Jerry and Tyree.

A CORRECTIONS OFFICER points me to a small TV monitor ensconced in a metal box, and a hard plastic chair. The telephone receiver has a 24-inch cord, trapping me underneath the TV. A camera sits on top of the monitor, and John Legend performs in the background on Live with Kelly and Michael. Outside the State Correctional Institution at Dallas, in northeastern Pennsylvania, it’s brilliant and clear.

The monitor flicks on, and Jerry pops into sight.

“I’m sorry, and I apologize. I guarantee. I’ve changed. I’m studying psychology to help me figure out the impact of my crime. I’ve been through 32 groups. I’m trying to understand. …

“I know it was wrong. I wasn’t raised bad. I got addicted to that lifestyle. … I didn’t want prison.”

Jerry is small, but he fills up the TV monitor. He sits upright, leaning into our conversation. His voice is direct, with underlying youthfulness. He’s warm and laughs easily, with a wide hyena smile. He’s someone I would consider being friends with, even though he nearly killed me.

There is little awkwardness in our first conversation. After his initial apology, we launch into his background, his childhood, his plans. A month before my visit, Jerry found out he’d made parole. A lot has changed since 2006. He reaches for the name of a product. Some kind of taco thing? Made of — what are they called? — Doritos! He’d like to try that.

He misses Checkers french fries and Wendy’s chicken nuggets, and he’s never held a smartphone. A fellow inmate told him about 3-D movies but warned he should ease himself into those.

He says his parents are going to pick him up on June 8th. They still live in West Philly; his dad’s in construction, his mom a homemaker. They help run St. James Soul Saving Holiness Church, where they’d hoped Jerry would someday become a pastor. As a kid he sat at the drum kit in the small, windowless chapel. He liked the drums because they turned something simple into something beautiful. He’d perch there in his suit until he grew bored, then would head to the bathroom to try and fall asleep. When his father caught on, he made him sit at the kit for the entire service, even after the music stopped. Jerry did not become a pastor.

His mom and dad were strict: no rap, early curfew. In the neighborhood, they had a saying: When the streetlights came on, Jerry and his siblings had to go home. If they didn’t make it, they’d have to pick out words from the dictionary, write down their definitions, then use them in a sentence. In the house, they’d listen to gospel, Kirk Franklin. Sometimes, while driving in the car with their dad, they’d flip on WDAS.

By ninth grade, school started to bore Jerry, so he skipped it and smoked weed in Upper Darby with his friends. His mom would drag him to school — literally walking him to first period — but he’d bolt before the end of the day. He’d figured out a way to make sure his parents didn’t find out, too: The school would always call exactly at 5 p.m. to let parents know a son or daughter had skipped class. All you had to do, Jerry learned, was be on the phone at 5 p.m. The school never tried a second call.

Jerry didn’t make it past ninth grade. He ran away from home, to live with a cousin off Girard Avenue, by the Zoo. He wasn’t very good at selling weed or coke, but he needed the money, so he did it anyway.

Tyree is taller than Jerry by a few inches, which matters when you find out how they became friends. Overbrook Park had a park, and that park had a basketball court. Tyree could jump all over that court, flying from baseline to baseline, leaping to block shots. Jerry could never get in on a game, until Tyree picked him one day.

This entire story might not have happened if Tyree Brown hadn’t felt bad for Jerry Price.

Tyree, in most ways, is the opposite of Jerry, though those opposites landed them in the same place. When he was six or seven, he walked into his single mother’s apartment and watched as an ex-boyfriend jumped out of the closet. Tyree tried to call the police, but the man cut the phone lines. The beating hospitalized his mother for months, costing her her nursing-home job.

“I couldn’t protect her,” he says. “It felt like the end of the world.”

Tyree graduated from Overbrook High while dealing on the side. He liked reading and science (“It’s fun, cutting up frogs and whatever”) and was proud of himself when he graduated. When I ask him whether — unlike Jerry — he was good at selling drugs, he laughs, says yes, then catches himself.

“I believe I had a choice, but I didn’t push myself down that road,” he says. “I wish like hell I took that road.”

On the outside, Tyree has a daughter, Lauren. She’s the same age as his prison term so far — nine. She writes, sends him pictures and emails. She’s a straight-A student, he says. Her mother and grandmother try to bring her up every few months.

When Lauren was eight, she visited the prison and sat outside with her dad. A guard walked over and informed Tyree he had 10 minutes left. Lauren asked who the man was, then walked over to him, tapped him.

“I’ll give you my chips if you let me stay with my dad.”

Tyree tries to be honest with her. This isn’t okay, he tells her. Do better. When she asks when he’s getting out, he says, “Soon.”

“When’s soon?”

The night after his daughter offered the chips, Tyree cried in his cell.

“I’ve watched her grow up in jail,” he says. “That’s the most painful thing: knowing I let her down. Years I’ll never get back. What can I do now to be a father? She’s supported, but still needs a father. That eats me up inside.”

AFTER ABOUT AN HOUR, I ask Jerry about the kidnapping. It wasn’t something they’d planned, he said; they just wanted money. Robbery was quicker and easier than dealing weed and coke, and the pay more immediate. No middlemen, no corners.

“I was fucked up at the time,” he says. “I was real messed up at the time. I didn’t have no regard for myself, so I wasn’t going to have no regard for anyone else.”

I bring up something the district attorney told me before I testified: that on that night, two of them had to convince the third not to kill me. That I was the first person they’d kidnapped with a real gun. Jerry assures me they were never going to kill me, that it was the D.A. scaring me into more damning testimony. They weren’t going to use the gun, Jerry said.

“Then why have a real gun?”

“If I go in with a fake gun and they figure it out, what do we do?”

I strain up to the camera, with a Then you stop fucking kidnapping people look. Jerry catches my eye and tells me sometimes the gun didn’t have any bullets in it. I launch into my memories of the gun, the cocking, the counting. Jerry looks down for three, five, seven seconds. The phone’s quiet. He looks up, and wipes his eyes. I apologize for asking about it and tell him it’s okay, that it’s in the past.

“No, it’s not okay. It’s never okay, for real, to put someone through that hurt. The best I can tell you is I’m better now. It’s not going to happen again.”

The conversation ends with that. We move on.

I SPEND THREE DAYS in and out of SCI Dallas. I grow to genuinely enjoy both Jerry and Tyree, so much so that afterward, I ask a guard what he thinks. Is this weird? Are they putting on an act for the sake of the parole board? “I guess, I don’t know,” he says.

The second day, I meet with each of them one-on-one, in the main visitors area. Wives and girlfriends stake out prime seats in a corner, close to the vending machines but away from the children, lining up and re-

adjusting their microwave pepperoni pizzas on the chairs next to them while they wait.

Kids run up and down a ramp, under the razor wire, and into their fathers’ arms.

On the third day, I meet with Jerry and Tyree together, at a table reserved for families. The walls are covered in Snoopy and Mickey Mouse and a pretty decent Bugs Bunny holding a carrot as a paintbrush. There, our new little family sits and talks and bullshits and watches as another family plays Uno.

March 27, 2006, is millions of miles away, happening to three different people. Those people came from contrasting worlds and polar communities, brought together by the happenstance and opportunity of West Philadelphia. Now, we’re bound together by that night, but no longer dragged down by it. Now, there are no nightmares, no anger.

Soon, Jerry will be outside again, eating Doritos tacos; Tyree’s up for parole next year. (Mordi has already been released, which is why I don’t visit him.) Our conversation turns to the outside, and with that, the most difficult question: What happens when you’ve spent one-third of your life in prison and you’re not even 30?

They both hope to work with at-risk youth, a noble if reasonable goal. Jerry should be fine; he’ll work for his dad’s construction company, a firm safety net underneath. He’s worried about normal things: catching the bus, seeing family members he hasn’t seen in nine years. (Jerry has published a book about his time in jail, a collection of poems and short stories called Even In The Dark The Sun Still Shines. A fellow inmate introduced him to his publisher, Angela Price, whose other titles include erotic fiction about anal sex. Jerry’s expanding her repertoire.)

Tyree … I worry for Tyree. He wants to open a barbershop, is taking business classes. I want him to succeed, to flourish for himself and for Lauren. But his voice belies his optimism. He’s practiced his spiel; the question is whether he believes it himself.

“I’m gonna hear a lot of no’s, but I just need that one yes. I’m not gonna give myself that excuse to go back to drugs or criminal activity. I gotta lift myself up.

“You gotta show them you want it. You gotta be up-front: ‘I made a mistake, a big mistake, and I acknowledge that.’”

We talk about the other victims for a bit, and I make sure it’s okay that I keep in contact with the two men, both inside and outside of prison, to check on their progress. As I’m getting ready to leave, I ask if they have any questions for me.

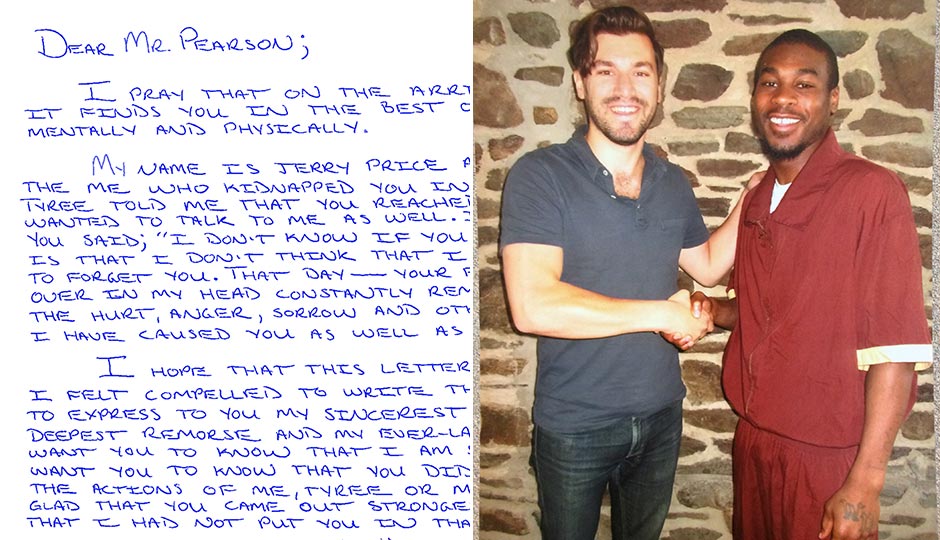

“This might sound weird, but would it be cool if we got a picture together?” Tyree asks. The visitors room has a small ad hoc photo booth, which in prison is just a stone wall, a decade-old digital camera and a printer. Jerry and I go first; he flashes a toothy ear-to-ear grin.

Tyree steps up and takes my hand. The inmate photographer looks at his first shot and shakes his head. He opens his mouth wide and sticks his tongue through the space where his four front teeth used to be.

“Smile!”

THE FOLLOWING DAY, I come to Philadelphia. I pass the spot where Jerry, Mordi and Tyree kidnapped me, retracing the route where my mind tells me I went that night.

I go looking for the lot they dropped me in, where the dirty leaves were clean and I was sure I’d die. I spend an hour driving the streets, up Haverford Avenue, down Girard. I sputter along on one-way side streets and through alleys, double-parking when I think something looks familiar. On my phone, I pull up the satellite map, looking for wooded areas and abandoned lots.

As I’m ready to give up, I find an overgrown yard, all rusted chains and stooped-over vehicles. It’s lonely; overhead, a lavender empress tree hangs lush from the spring rains. I shimmy to the side of the empty street and lean across the passenger seat, craning to place a memory. There are no cedars, only a needle-less Christmas tree tossed over the fence.

I take a few pictures, roll up the window, and head for home.

Left: Jerry Price’s first letter to the author. Right: The author and Jerry after their prison meetings.

Originally published as “My Kidnappers” in the September 2015 issue of Philadelphia magazine.