Should Temple Have Investigated Bill Cosby in 2005?

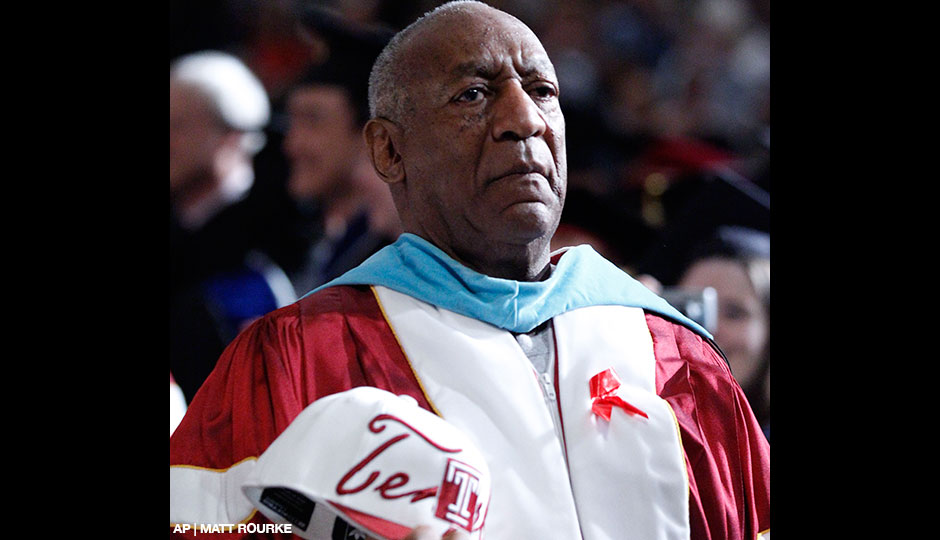

Comedian Bill Cosby at Temple University’s commencement Thursday, May 12, 2011, in Philadelphia.

Temple University is in a strange place these days.

Though the sexual-assault accusations that have sullied the once-exalted name of Bill Cosby span decades — not to mention the country — the university on North Broad Street has found itself the uncomfortable ground zero of the scandal.

Andrea Constand, after all, was an employee of Temple when she met — and, she alleges, was assaulted by — Cosby, who was then not just the school’s most famous alumnus but a member of the university’s board of trustees. Constand’s March 2005 civil suit against Cosby offered the public its first real hint that “America’s Dad” might have a darker side. And the dozen Jane Does who were ready to testify on Constand’s behalf to allegedly similar experiences with Cosby suggested, too, that the whole thing could mushroom.

But Constand’s lawsuit was settled and sealed in October 2006, and no criminal charges were ever filed against Cosby. In the absence of an official, public verdict on his alleged behavior, and thanks in no small part to an aggressive PR offensive waged by the comedian to keep the stink of scandal off his still-good name, America was all too happy to forget about the allegations. And so too, it seemed, was the school.

The comedian continued his high-profile association with Temple — raising money and speaking at graduations and freshman orientations, even hobnobbing with President Clinton at the memorial service for another high-profile trustee, Lewis Katz, last summer. It was only after the scandal blew up anew last fall — after a comedian’s joke to a Philadelphia audience was recorded by Philadelphia magazine’s Dan McQuade and went viral, and many new women came forward with claims of druggings and sexual assault — that the association became untenable. Amid intense public scrutiny, Cosby resigned his membership on the board late last year.

If, during that decade, anybody within Temple expressed concern that the university was promoting, basking in, and profiting from associations with a man accused of raping one of the institution’s employees, it didn’t register publicly. The posted minutes from board meetings during the two years the suit was active mention Cosby only once — to note his absence from the meeting.

One might think that a university employing and educating thousands of women had an obligation to look into allegations that one of its most high-profile trustees was accused of a pattern of deviant and/or predatory sexual behavior with young, impressionable women. But determining how the university responded — if at all — to Constand and her 12 Jane Does in 2005 is difficult. For this story, Philadelphia magazine attempted to interview more than a dozen current and former employees, administrators, and trustees to seek their recollections of what steps the university took when Constand’s allegations were made public. Only two agreed to comment — and both pleaded faulty memory of specifics about the case and the time.

Which leaves two very big questions unanswered by the university and its associates:

- At the time Constand’s allegations became public, was there any move on the part of the board or administration to investigate or otherwise address her allegations and their potential ramifications for the university community at large?

- Should Temple now reexamine its 2005 response to those allegations?

The person best positioned to answer those questions is, paradoxically, also the person worst positioned. Patrick O’Connor, the bellicose legal titan and vice chairman of the formidable Cozen O’Connor law firm, was a member of Temple’s board of trustees in 2005; he has been the body’s chair since September 2009. But he is also, significantly, Bill Cosby’s defense attorney in the Constand legal case, which, after lying dormant for years, has resurfaced with a vengeance. Which means the Temple University official with the most detailed knowledge of the allegations against Cosby has, due to the obligations of attorney-client privilege, presumably been using that information on Cosby’s behalf, not the university’s.

It would be a mistake, however, to put the burden of Temple University’s handling of the Cosby allegation solely on O’Connor’s shoulders. Constand’s allegations were widely reported in 2005 and 2006. In the still-churning wake of the Jerry Sandusky scandal at Penn State, it seems necessary to ask again: Did anybody at Temple University do anything about them?

Few Answers

Bill Cosby on stage during Temple’s commencement ceremony on May 12, 2011.

Dawn Staley, a close friend of Cosby’s who was then Temple University’s women’s basketball coach — and the woman who hired Constand at Temple — declined to comment through a spokesman at the University of South Carolina, where she is now head women’s basketball coach. U.S. Appellate Judge Anthony Scirica, then and now the vice chair of Temple’s board of trustees, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Howard Gittis, the board chair from 2000 to 2006, died in 2007. There was no response from Bill Bradshaw, then the athletic director, whom Philadelphia attempted to reach through the university. Attempts were also made to contact a number of that era’s surviving board members.

David Adamany, who was Temple’s president at the time, said he doesn’t remember news of Constand’s lawsuit reaching his desk — by that time, he noted, Constand was no longer working for the university.

“I don’t remember this, and I think the reason I don’t remember this is because it wasn’t a lawsuit against the university,” Adamany said. “He wasn’t being sued in his capacity as a trustee. It seems to me to be a lawsuit between two people” who happened to have university affiliations.

Nelson Diaz, former Philadelphia city solicitor, judge, mayoral candidate, and longtime Temple board member, sounded a similar note. “I never heard anything at all until the [recent] publicity started,” he said. “It doesn’t mean it didn’t come up, but I don’t remember it.”

There was one member of Temple’s leadership who was privy to all the details of the case, though: O’Connor.

Should he have said something in the intervening decade? It’s hard to see how he could have: The requirements of attorney-client privilege and the seal on the case could well have made any disclosure an act of career suicide. And while Cosby made lurid admissions in a 2005 deposition in the Constand case — in which the comedian described using his money and fame to seduce women, and admitted giving drugs to young women with whom he wished to have sex — he never admitted to nonconsensual sex. O’Connor could make the case that there was nothing to report.

Nonetheless, O’Connor has come under fire from critics who suggest a conflict of interest: How could he represent Cosby in the case while looking out for the university’s welfare at the same time?

“At this point, I think it’s awfully embarrassing … that O’Connor is still defending Cosby,” Art Hochner, president of Temple’s full-time faculty union, said recently.

Jerry Reisman, a New York lawyer who specializes in nonprofit board governance, said O’Connor should have resigned from the board when he began to represent Cosby in Constand’s lawsuit.

“There’s an old saying for lawyers: ‘If it doesn’t pass the stomach test, step aside,’” Reisman told Philadelphia. O’Connor, he said, “didn’t do that.”

Criticisms, Conflict?

Temple officials have vigorously defended O’Connor against such criticisms, saying his representation of Cosby “was disclosed and vetted in accordance with Board policy.” The university put out a statement in late July from president Neil Theobald and Daniel Polett, who succeeded Gittis as board chair and served through August 2009, endorsing O’Connor’s leadership and ethics.

“Mr. O’Connor’s representation of Mr. Cosby was disclosed to the board at the time of the representation,” a Temple University spokesman said in response to Philadelphia’s inquiries.

However, Temple would neither document nor specify a date or manner of that disclosure despite repeated requests. Instead, a university spokesman pointed to a web page featuring university policies. One policy — updated in 2008 — describes various situations under which trustees may have conflicts of interest. One of the scenarios it draws is when “a Trustee believes his or her independence of judgment is or might appear to be impaired by an existing or potential financial or other interest.”

The written policy concedes that it may not “resolve every question” about conflicts of interest — advising, in the case of uncertainty, that a trustee should seek the advice of counsel.

Temple officials, for their part, don’t necessarily concede that a conflict exists.

“Please note that disclosure of any particular situation — in this case, Mr. O’Connor’s representation of Mr. Cosby in a civil matter brought by a former employee — does not presuppose the existence of a conflict,” the university spokesman said via email.

Abraham Reich, co-chair at the Fox Rothschild law firm, teaches an ethics course at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and frequently writes on legal ethics. He talked to Philadelphia magazine at the request of O’Connor’s firm, Cozen O’Connor.

“Pat’s been accused of conflict of interest and a bunch of other accusations that I don’t think are well-founded,” Reich said, later adding, “I think as a lawyer, Pat has taken a bad rap by the press.”

O’Connor, he said, never tried to influence Temple’s actions regarding Cosby after taking the comedian on as a client. “There’s no suggestion that Temple’s interests were impaired by that representation,” Reich said. “When it came to the Cosby issues, he did not participate in those discussions or decisions.” (A Temple spokesman could not confirm when or whether the board discussed the allegations against Cosby, but emphasized that such discussions would have happened in closed sessions.)

Reich’s conclusion about O’Connor: “I think he acted appropriately.”

Remedies

But O’Connor was not, of course, the only person in a position of responsibility. The question remains: Did anybody else at Temple do anything about the allegations? Did anyone even try?

Temple’s representatives have seemed to suggest that not enough was known about the allegations at the time. “The administration of Temple University knew nothing of the previously sealed disclosures about Bill Cosby that have recently appeared in the news media,” the university said in a prepared statement issued after Cosby’s testimony in the Constand case was unsealed. “To our understanding, this deposition was subject to a confidentiality order and only those involved in the case were privy to its contents.”

But Constand’s allegations were widely reported at the time. The topic was featured several times on Dan Abrams’s prime-time show on MSNBC during the early part of 2005. The Daily News helped break the story, while the Inquirer reported prominently on Montgomery County D.A. Bruce Castor’s decision not to bring criminal charges against Cosby in February of the same year. Robert Huber’s “Dr. Huxtable and Mr. Hyde” appeared in Philadelphia magazine in June 2006.

The Inquirer story on Castor’s decision indicated that he’d interviewed “the woman’s family, friends and coworkers” before arriving at a decision. Castor confirmed to Philadelphia magazine this week that those coworkers likely would have included Temple employees — although Castor said his own memory has gotten fuzzy on specifics in the intervening decade.

“It would’ve been ordinary procedure that we would’ve interviewed the employers of Andrea,” Castor said.

Indeed, a Temple spokesman answering questions about the matter acknowledged that there was “extensive contemporaneous print and television coverage” at the time of the allegations. If you were in any way connected to Temple — and responsible for the care of the university and its public image — the story was essentially unavoidable.

Given that widespread knowledge, some experts say the broader board of trustees should have initiated its own investigation of the matter. Indeed, the university’s current sexual harassment policy seems to cast a wide net of responsibility in such matters, saying that “all members of the university community have a responsibility to insure that the university is free from all forms of sexual harassment.”

“They should certainly do a full investigation, at a minimum,” Reisman said of boards facing similar situations. “They should certainly come to a conclusion, internally, if the act requires the immediate removal of the person from the board. In this case, the (alleged) act was so serious there should’ve been a very serious investigation conducted by the university at that time. And if Mr. Cosby refused to cooperate, they should’ve removed him.”

Charles Elson, director of the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware, said a board isn’t always required to investigate alleged wrongdoing by its members — but Constand’s relationship to the university made it imperative to take a close look.

“If an allegation involves a trustee and an employee of the university, you can’t look the other way. It has to be handled appropriately,” Elson said. “What kind of response is justified is up to the board. No response at all, or looking the other way, is problematic.”

What Next?

Fox Rothschild’s Abraham Reich says an independent investigation would have had its own troubles. Fact-finders from the university could not have compelled testimony from Constand or Cosby, he said, and in the absence of that information, what could an independent investigation have accomplished?

If the result of Temple’s inaction is that the university was closely associated with its now-tarnished alum for another decade, Reich said, “I don’t know that in the end, it made that much of a difference. … Show me where in that hiatus [of a decade] there is any harm to Temple.”

A fair point, perhaps. More than 40 women have come forward with allegations against Cosby — but none reporting incidents that allegedly happened after Constand filed her lawsuit, and none of them involving Temple University. Perhaps no more damage was done.

This is also true, though: Bill Cosby was accused of sexually assaulting a Temple University employee. He was neither charged nor convicted of a crime — and hasn’t been to this day. But neither was he exonerated. Despite that ambiguity, Temple officials chose to celebrate and promote Cosby — as an example to its freshmen, as an example to its grads, as an example to the world of the university at its finest.

The university, it appears, chose amnesia. So did much of America. Is there harm in that?

Grace Holleran, who wrote an editorial for the student-run Temple News last year titled “Stop Revering Cosby,” said she believes Temple’s silence on the matter has helped create a climate where women might be afraid to come forward with accusations of assault.

“It seems like they didn’t want to be inconvenienced by a scandal,” she said of the university.

Which is why, perhaps, members of the university community say it’s now time for Temple to examine its handling of the allegations — or perhaps hire outsiders to come in and do it for them. But the impetus (or at least approval) is going to have to come from the board of trustees, observers say.

“I think they should look into it now,” faculty union president Art Hochner said.

Nelson Diaz said the topic of sex abuse is “very important,” but when asked if he would support a new investigation, he added: “I shouldn’t comment. I’m a board member. I shouldn’t comment.”

Some observers say Temple needs to do something to restore credibility — both for its public image and to assure women in its community that the university takes sexual assault seriously.

“From Cosby to campus rape, rape victims are profiled as liars,” said Carol Tracy, director of the Women’s Law Project in Philadelphia. “Society has to stop doing that. Start believing and start protecting.”

Follow @JoelMMathis on Twitter.