Realness: Gerard Gaskin on Queer Ball Culture and His New Philly Exhibit

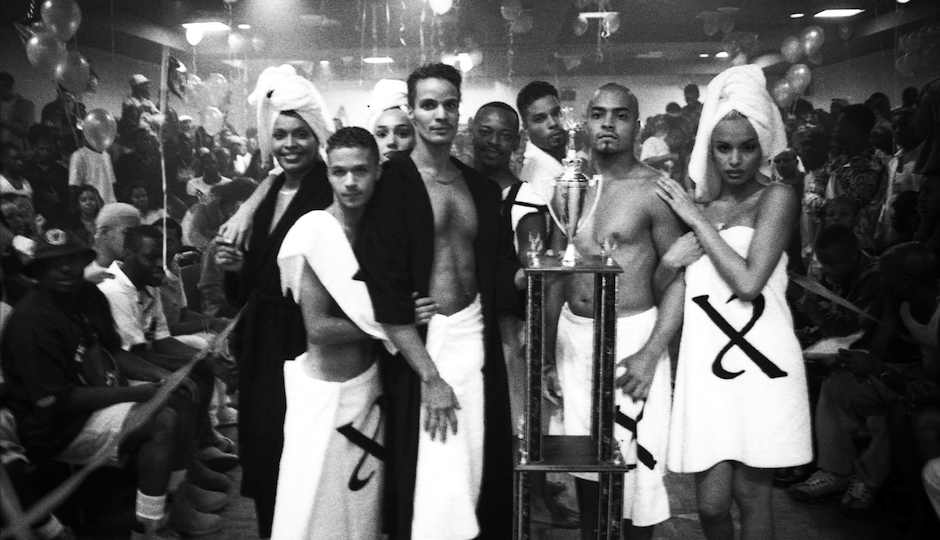

Members of the House of Xtravaganza at the Marc Ballroom in Manhattan, NY 1997, by Gaskin.

Gerard Gaskin knows realness when he sees it: He’s been photographing the gay/queer ball scene for over 20 years, and when I asked him what was his most memorable shoot, he tells me about two separate balls. The first, pictured above, was in 1997 New York, featuring the famed House of Xtravaganza (you probably know them from the cult documentary Paris is Burning) performing a highly choreographed number featuring a full-sized sauna that was wheeled on stage.

“They came out of that sauna and there was smoke everywhere,” Gaskin said. “After they won, the whole place was filled with smoke, and the trophy was taller than them. It really was an amazing moment.”

His other favorite shot comes right here in Philly, and it involves a coffin.

“There were henchmen with hoods and capes, like in the old movies,” he said. “Six people came out with this coffin, and this guy jumps out of the coffin, looking like Benjamin Franklin, with the long white socks and the half-boot shoes and the ruffles on the shirt. He comes out and basically starts dancing on the runway. It really says a lot to me and to the scene with how they play with pop culture, culture, and history in general.”

Both of these memorable moments are featured in Gaskin’s exhibit at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. Aptly titled Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene, the show features dozens of Gaskin’s photographs that examine ballroom culture through the years, and although times have changed, the fundamental reason people go to these balls remains relatively steadfast.

The “casket” dancer from Gaskin’s exhibit.

“The base of the space is the same,” he said. “It’s for queer people of color to come and examine sexuality. On that basic, basic level, that’s what these balls are for. When I first started photographing the balls, it was an underground culture. You only knew there would be a ball if you knew someone who was part of the scene already. Now, you can go on Facebook and find ball flyers or advertising.”

“The space ultimately allows people to develop confidence about who they want to be,” he continued. “Ultimately, the cool thing about the balls that you have to remember is that the judges are their peers. They create categories: They play with how the outside world sees them, and how they see the outside world.”

Of course, those categories have become somewhat notorious in gay culture, especially if you’ve ever seen the above-referenced Paris is Burning (“Butch Queen,” anyone?). But behind what may appear to be all fun and games, there’s a sociological reason why queer people of color developed these competitions and categories, as Gaskin explained.

“There’s all of this talk about ‘realness,’ which pretty much is poking fun of how [these participants] see the straight world,” he said. “I can dress up and act like an executive, or a school boy, or a thug, or whatever. I can pass if I want. That’s poking fun of the outside world. People from the outside world are the ones who are really ‘real,’ or straight. The space is profound because it’s a play between how do we as queer men or color or queer women of color deal with then having the enter into a world and be confident enough to succeed? You have to develop a thick a skin, a certain sense of self.”

So could this underground ballroom culture lead to some sort of a racial breakthrough in how we, in the gay community, examine each other via social and racial lenses?

“It depends on if the outside world is interested in listening or not, that’s the thing,” replied Gaskin. “Ultimately, whoever comes to the balls ‘gets it,’ and that’s the reason why they come.”

You can view ‘Legendary’ through August 16th. For further information, visit the African American Museum’s website.